This originally ran on Comixology.

____________________

“Super-hero” backwards is “noir.” The opposite of the upright avatar of justice with entirely sublimated sexual urges is the morally ambiguous anti-hero driven by money-lust and just plain old lust. The super-hero wears his underwear on the outside and saves the universe; the noir hero curses the universe and is pulled around by what’s inside his underwear. Noir is about shadows and helplessness and the best-laid illicit plans ending up in ruins; super-heroes are about light and empowerment and the best-laid illicit plans ending up in ruins.

“Super-hero” backwards is “noir.” The opposite of the upright avatar of justice with entirely sublimated sexual urges is the morally ambiguous anti-hero driven by money-lust and just plain old lust. The super-hero wears his underwear on the outside and saves the universe; the noir hero curses the universe and is pulled around by what’s inside his underwear. Noir is about shadows and helplessness and the best-laid illicit plans ending up in ruins; super-heroes are about light and empowerment and the best-laid illicit plans ending up in ruins.

Which is to say that, while super-heroes and noir appear at first to be irreconcilable, on closer look they do have a fair bit in common. They’re both male genre literature. They both have a strong moral code enforced by corporal punishment. And they both have, shall we say, ambivalent feelings about women. It makes sense, then, that there’s a long tradition of combining the two, starting at least with the first Batman stories, reaching its high point, I firmly believe, with Bob Haney’s goofily brilliant Batman/Deadman team up in Brave and Bold #101, and continuing on to this day with anything Frank Miller has ever touched (including, of course, Batman.)

One of the most interesting super-hero/noir mashups I’ve seen is the 1986 Punisher mini-series Circle of Blood by Steven Grant and Mike Zeck. The Punisher has always been only sort-of/kind-of a super-hero. He wears tights, but merely, you sense, because that’s the best way to stay inconspicuous in the hero-ridden Marvel multiverse. He fights for truth and justice, but he does it by shooting people.

Steven Grant is well known for his writing about comics as well as for his comics themselves (he did some guest-writing on my blog not too long ago), and you can see his critical acumen in his script. Basically, where Frank Miller tends to use noir to make his heroes seem even more bad-ass, Grant uses it to question and ultimately undermine the moral certainties on which the super-hero genre is based.

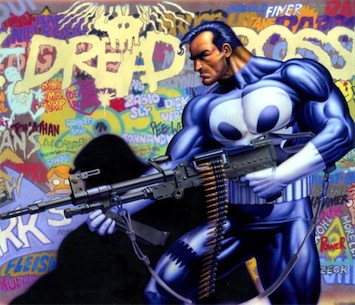

Zeck draws the Punisher as a pumped-up manly-man whose bobble-head is dwarfed by acres of steroidal flesh, and this is a good metaphor for the way Grant writes the character. From the neck down, the Punisher is a super-hero juggernaut, hyper-competently disposing of roomfuls of thugs in classic Bat-mode, or bashing his way through a prison in a fashion reminiscent of the contemporaneous Rorschach.

From the neck up, though, the Punisher isn’t hyper-competent at all. Instead, he’s more like the classic noir dupe. Though he has a certain tactical animal cunning, his inner monologue is obsessively repetitive in a way that suggests borderline idiocy — where Batman’s traumatic backstory has, supposedly, made him smarter, the Punisher’s has left him, in Grant’s writing, a monomaniacal mental and emotional basket-case. The Punisher is, like most noir men, childishly easy to fool. He stumbles into traps, is bamboozled by a shady conglomerate called the Trust, and, inevitably, betrayed by a woman. His solve-it-by-shooting-it approach to every problem results in heaps of dead bodies, including that of one child. Said child’s death sends our hero into a self-pitying funk, complete with flashbacks and profound utterances (“It’s got to stop. The poor children.”) which, at least from my perspective, makes him appear more damaged, dangerous, unsympathetic, and unheroic than ever.

The Punisher’s final act in the comic is to allow the woman who betrayed him (Angela) to fall off a cliff. His motivation seems less abstract justice than simple spite, and one has to wonder, as he limps off into the sunset, whether the world wouldn’t maybe be a safer place if the bad guys had won and offed this dangerously imbecilic killing machine. The use of noir here actually, and I think intentionally, calls the whole concept of super-heroics into question. The hired thugs in the series are dressed in the Punisher outfit and actually believe themselves to be the Punisher — and the parallel is quite clear. The Punisher himself, after all, seems like a brainwashed sleepwalker, not to mention a criminal. In the not-light of noir, the super-heroic law-and-order certainties become naïve, dangerous idiocy, while righteous vengeance turns into a flimsy excuse for self-aggrandizing fascistic violence.

Of course, you can turn this around and argue that the super-hero genre actually validates noir’s amorality. Just because Grant portrays the Punisher as a dangerous numbskull doesn’t mean that readers will stop identifying with him. He’s the hero, after all, and when, in his quasi-sentient way, he lets Angela fall to her death, you can certainly hear a chorus of “yeah, kill the bitch!” echoing from the peanut gallery. Does breaking a man’s little finger make Rorschach a monster, or does it make snapping people’s fingers seem kind of cool?

Probably both. Super-heroes and noir are polar opposites — but on a magnet, the poles are, of course, closely attached. Like Westerns, spy thrillers, and most male genre literature, both super-hero and noir are built around an exciting frisson of justified violence — a circle of blood. If you want to break out of that circle, you probably need to reach for a less closely-allied genre, or else try to dispense with genre altogether. Once you do that, of course, you’re talking to a much smaller audience, and not writing for a mainstream comics publisher. The irony is that by creating a thoughtful, popular comic questioning the Punisher’s war on crime, Grant probably helped to make that kind of war — with its more explicit blood, sex, and amorality — a mainstream staple.