Can reading detective fiction and Superman literature turn you into a supervillain? Super-lawyer Clarence Darrow says yes. He argued his case this week in 1924.

The facts were indisputable. His clients, Dickie Loeb and Babe Leopold rented a car, picked up Dickie’s fourteen-year-old cousin Bobby from school, and bludgeoned him with a chisel in the front seat. After stopping for sandwiches, they stripped the body, disfigured it with acid, and hid it below a railroad track. When they got home, they burnt their blood-spotted clothes and mailed the parents a ransom note. It was the perfect crime.

Dickie was nineteen, Babe twenty, but both had already completed undergraduate degrees and were enrolled in law schools. They were also both voracious readers. Darrow, their defense attorney, detailed Dickie’s literary tastes: “detective stories,” each one “a story of crime,” ones, he said, the state legislature had wisely “forbidden boys to read” for fear they would “produce criminal tendencies.” Dickie “devoured” them. “He read them day after day . . . and almost nothing else.”

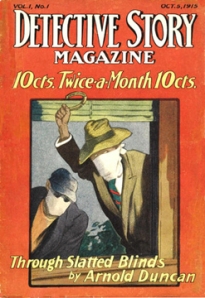

Darrow didn’t mention any titles, but Dickie must have snuck stacks of Detective Story Magazine past his governess. The Street and Smith pulp doubled from a bi-monthly to a weekly the year he turned twelve. Johnston McCulley was a favorite with fans. His gentleman criminal the Black Star wears a cape and hood with an emblem on the forehead. So does his Thunderbolt. Darrow said Dickie’s pulps “all show how smart the detective is, and where the criminal himself falls down.” But the detectives chasing the Man in Purple, the Picaroon, the Gray Ghost, the Joker, the Scarlet Fox—they never catch their man. Those noble vigilantes remain safely outside the law. They are also all young men born into wealth who disguise their secret lives. So Dickie, the son of a corporate vice-president, learned to play detective, “shadowing people on the street,” as he fantasized “being the head of a band of criminals.” “Early in his life,” said Darrow, Dickie “conceived the idea of that there could be a perfect crime,” one he could himself “plan and accomplish.”

Babe was an impressionable reader too. He’d started speaking at four months and earned genius level IQ scores. Darrow called him “a boy obsessed of learning,” but one without an “emotional life.” He makes him sound like a renegade android, “an intellectual machine going without balance and without a governor.” Where Dickie transgressed through pulp fiction, “Babe took to philosophy.” Instead of McCulley, Nietzsche started “obsessing” Babe at sixteen. Darrow called Nietzsche’s doctrine “a species of insanity,” one “holding that the intelligent man is beyond good and evil, that the laws for good and the laws for evil do not apply to those who approach the superman.” Babe summed up Nietzsche the same way in a letter to Dickie: “In formulating a superman he is, on account of certain superior qualities inherent in him, exempted from the ordinary laws which govern ordinary men.” A member of “the master class,” says Nietzsche himself, “may act to all of lower rank . . . as he pleases.” That includes murdering a fourteen-year-old neighbor as one “might kill a spider or a fly.”

So Babe considered Dickie a fellow superman. And Dickie considered Babe a perfect partner in crime. The two genres have one formula point in common: heroes are “above the law.” When Siegel and Shuster merged Beyond Good and Evil with Detective Story Magazine in 1938, they came up with Action Comics No. 1. Loeb and Leopold only got Life Plus 99 Years, the title of Babe’s autobiography. Prosecutors wanted to hear a death sentence, but Darrow wrote a modern law classic for his closing argument. It brought the judge to tears.

William Jennings Bryan liked it too. He quoted excerpts during the Scopes “Monkey” trial the following year. Bryan was prosecuting John Scopes for teaching the theory of evolution in a Tennessee high school, and Darrow was defending him. Scopes, a gym teacher subbing in science, used George William Hunter’s school board-approved Civil Biology, a standard textbook since 1914, and one that shocks my students when I assign it in my “Superheroes” course.

“If the stock of domesticated animals can be improved,” writes Hunter, “it is not unfair to ask if the health and vigor of the future generations of men and women on the earth might not be improved by applying to them the laws of selection.” After describing families of “parasites” who spread “disease, immorality, and crime,” he argues: “If such people were lower animals, we would probably kill them off to prevent them from spreading. Humanity will not allow this, but we do have the remedy of separating the sexes in asylums or other places and in various ways preventing intermarriage and the possibilities of perpetuating such a low and degenerate race.”

This was one of Bryan’s main objections to evolution, a term he used interchangeably with eugenics: “Its only program for man is scientific breeding, a system under which a few supposedly superior intellects, self-appointed, would direct the mating and the movements of the mass of mankind—an impossible system!”Bryan links eugenics to Nietzsche, as Darrow had the year before, saying Nietzsche believed “evolution was working toward the superman.” The claim is arguable, but the superman was “a damnable philosophy” to Bryan, a “flower that blooms on the stalk of evolution.”

“Would the State be blameless,” he asked, “if it permitted the universities under its control to be turned into training schools for murderers? When you get back to the root of this question, you will find that the Legislature not only had a right to protect the students from the evolutionary hypothesis, but was in duty bound to do so.”

Darrow declined to make a closing argument, preventing Bryan from making his before the judge too, so their final debate played out in newspapers. Either way, Darrow was talking from both ends of his ubermensch. “Loeb knew nothing of evolution or Nietzsche,” he told the Associated Press. “It is probable he never heard of either. But because Leopold had read Nietzsche, does that prove that this philosophy or education was responsible for the act of two crazy boys?”

Perhaps Darrow’s hypocrisy is an illustration of a superman only obeying his own laws. It didn’t matter though. Like Loeb and Leopold’s, Scopes’ guilt was never contested, and the court fined him $100 (later overturned on a technicality). That was 1925, the year the Fascist-inspired “super-criminal” Blackshirt joined Zorro and his merry band of pulp vigilantes, while Adolf Hitler’s Mein Kampf climbed the German best-seller list.

Superman was ascending.