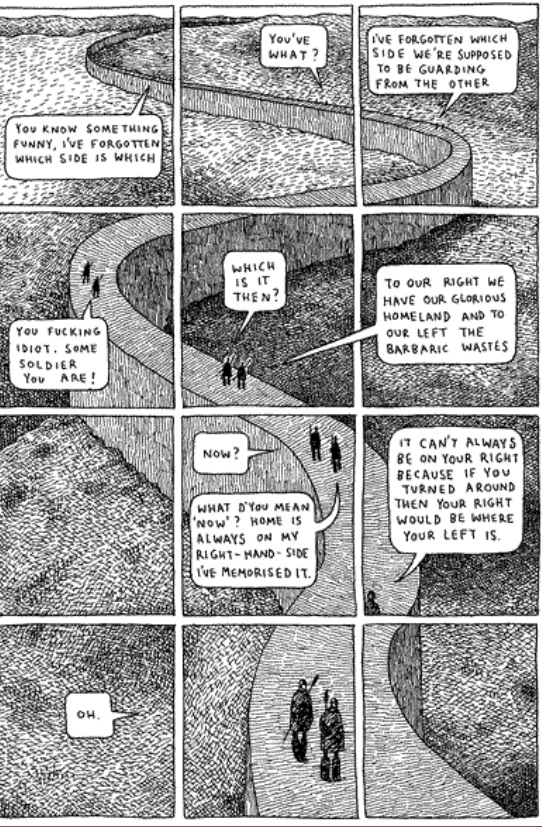

Reading a comic book is easy–even when there are no words to be read. You just look at a picture, and then at the next picture, and so on. But why do any of them make sense side-by-side? What is your brain doing as it leaps from image to image?

In Understanding Comics, Scott McCloud defines the Gestalt psychology principle of “closure” as the “phenomenon of observing the parts but perceiving the whole” (though it more specifically indicates a viewer filling in visual gaps between disconnected parts) and applies it to comics gutters: “Nothing is seen between panels, but experience tells you something must be there!” He goes on to explain: “Comics panels fracture both time and space, offering a jagged, staccato rhythm of unconnected moments. But closure allows us to connect these moments and mentally construct a continuous, unified reality.”

McCloud focuses his analysis on gutters and therefore types of transitions possible between panels (though closure is independent of panels and gutters, since insets and interpenetrating images work the same ways). He comes up with six types:

They work reasonably well, but his focus on panel transition has always struck me as slightly off. When I use it in class, students often don’t come to a clear consensus when analyzing any particular panel sequence. Moment-to-moment and action-and-action, for instance, are often ambiguous, sometimes combining identical leaps in time. And since actions do occur in McCloud’s moment-to-moment examples (a women blinks!), it’s not exactly clear what constitutes an “action.” Aspect-to-aspect can also be indistinguishable from subject-to-subject, both of which may or may not involve a movement in time, and so may or may not also be moment-to-moment or even action-to-action. And scene-to-scene might be a location leap and so also a kind of aspect-to-aspect at the big picture level, or a scene-to-scene can be in the same location but at a different time–so then how much time has to pass for an old scene to become a new scene?

These are annoying questions, but they really do come up when you try to breakdown a panel sequence with a roomful of students. So instead of categorizing transitions, my colleague Nathaniel Goldberg and I categorized types of closure while drafting our essay “Caped Communicators: Conversational Depiction and Superhero Comics.” Instead one all-purpose “perceiving the whole” process, we see four very different kinds of closure, each of which can occur by itself or in combinations.

Spatial: Subject matter drawn in separate images is depicted as existing in physical relationship to each other, typically as a result of panel framing. (What McCloud identifies as aspect-to-aspect, subject-to-subject, and some scene-to-scene transitions require spatial closure.)

Temporal: Undrawn events are depicted to take place outside of events drawn in separate images, typically as a result of panel transitions and so occurring as if in gutters. (What McCloud identifies as moment-to-moment, action-to-action, and some subject-to-subject and scene-to-scene transitions require temporal closure.)

Causal: Drawn action is understood to have been caused by an element absent from a current image but drawn in a preceding image. (None of McCloud’s transitions, not even action-to-action, accounts for this type of closure.)

Associative: A metaphorical relationship is depicted between two images in which one image is understood to represent some idea about the other image. (Though McCloud does not identify this type of closure, Jessica Abel and Matt Madden in Drawing Words Writing Pictures add “symbolic” to McCloud’s list of transition types. Such symbolic transitions require associative closure.)

It always helps to look at specific examples, so consider this three-panel sequence at the top of page 28 in Watchmen #8:

In the first image, artist Dave Gibbons draws the shadow of a statuette cast over the face of a frightened man lying on the floor. The second image shows the statuette in the fist of an attacker. Taken together, spatial closure is required to understand that the two images occur within a few feet of each other, each image drawn from one of the two men’s points of view. The second image also requires temporal closure because the statuette is behind the attacker’s head at an angle that would not cast the shadow seen on the victim’s face in the first image. Gibbons therefore also depicts a movement forward in time during which the attacker has cocked his arm back to strike.

The third image depicts a jack-o-lantern crashing to the floor with some falling books. It uses all four forms of closure. The pumpkin exists in the same space as the two now undrawn men (spatial closure). The pumpkin is crushed at a moment immediately following the second image (temporal closure). The falling books have been knocked down by the now undrawn attacker of the previous image (causal). And, because it resembles a human head and breaks open at the moment a reader anticipates the statuette striking the man’s head, Gibbons implies that the man’s head has been similarly damaged (associative).

A close reading of the sequence also reveals some confusion. Regarding causal closure, it is unclear how the attacker overturned the books at this moment since the act of swinging the statuette at the victim on the ground does not clearly involve his intentionally or unintentionally knocking over the bookcase in the same gesture. Instead, Gibbons may have attempted to suggest that the attacker struck his victim and then afterwards overturned the bookcase—an ambiguous two-step action otherwise absent.

I’m guessing Gibbons was fulfilling a directive in Alan Moore’s famously meticulously detailed script, producing this unintended gap in its execution. To address panel transitions that cause only confusion, McCloud includes “non-sequitur” as a type of transition that “offers no logical relationship between panels whatsoever!” So then a non-sequitur produces no closure at all–and so isn’t really type of closure, but is the absence of closure. Which is why we don’t include it as our fifth category.

So our closure types are deeply indebted to McCloud, but I think they also improve on his. I’ll be testing these out in my classroom soon, so hopefully my students will agree. More on that later.