The new Netflix series Narcos tells a story of Pablo Escobar’s construction of a gangster capitalist empire centered on the cocaine trade and the Drug Enforcement Agency’s (DEA) efforts to capture or kill him. Narcos opens with an uncredited quote from Matthew Strecher: “Magical realism is defined as what happens when a highly detailed realistic setting is invaded by something too strange to believe.” Neither that the quote is wholly inapplicable to the story nor that it is uncredited and grabbed from Wikipedia’s introductory paragraphs on magical realism are surprising given the story that follows.

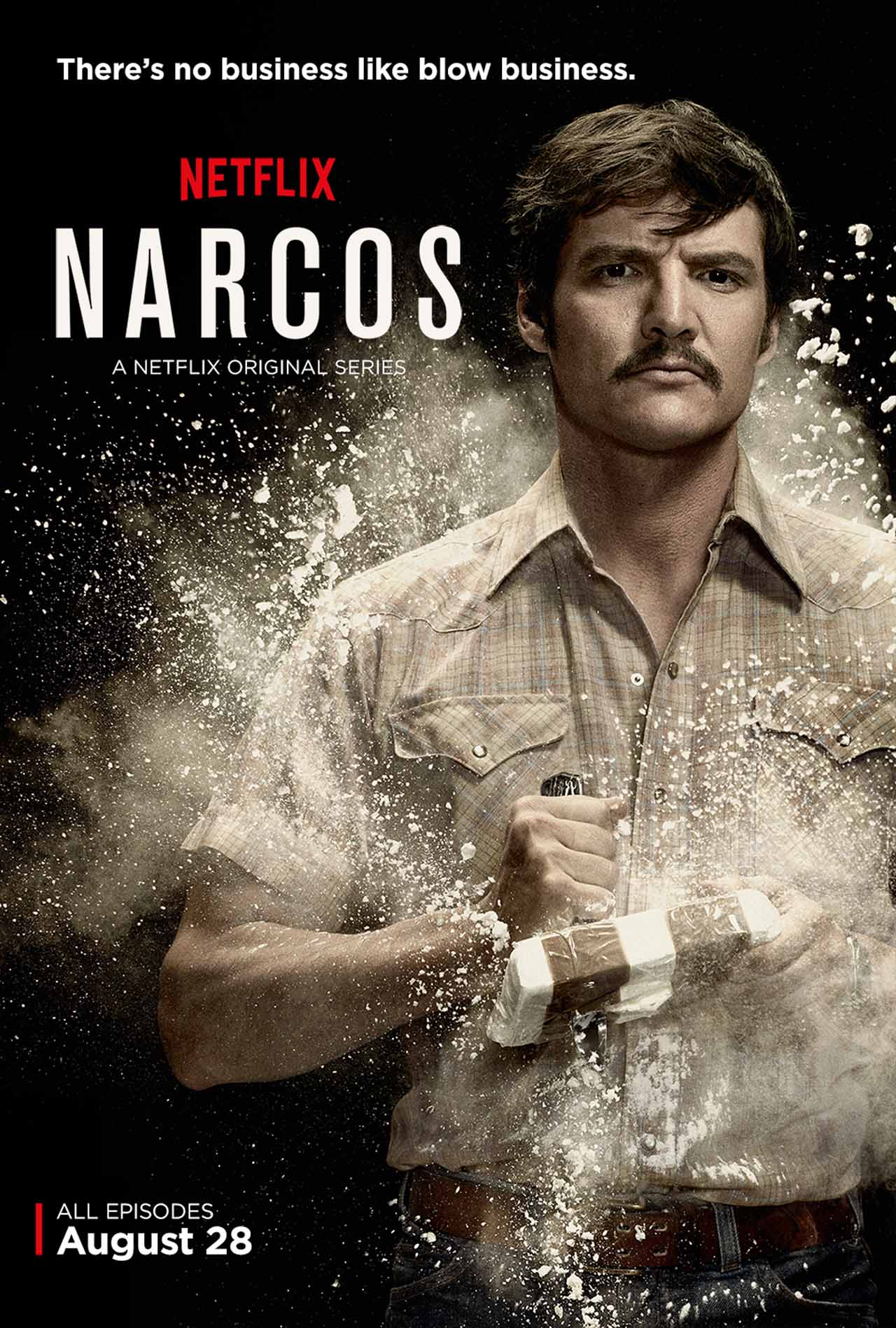

Wagner Moura plays Escobar, the Colombian narcotraficante par excellence who teams with his cousin Gustavo (Juan Pablo Raba) to found the anchor of what became the Medellín Cartel. The pair are hunted by DEA agents Steve Murphy (Boyd Holbrook) and Javier Peña (Pedro Pascal) and Colombian cop Horatio Carrillo (Maurice Compte). How exactly that happens is the meat of the story. And despite a s a slew of fine performances, solid photography and high production values, the meat is rancid.

A Badly Drawn Story for White Americans

Chris Brancato and Paul Eckstein are the team behind Narcos and they previously collaborated on Hoodlum, a film notable for Laurence Fishburne’s performance and for the extreme divergence in its best concept/worst script pairing. Just as they poorly imagined the Harlem numbers game, so too do they mangle the Escobar story from every angle and do so to to tell an American story in Colombia for a white American audience. Empire’s subjects do not have a voice.

Narcos is one of few shows to have significant Spanish and English dialogue. In contrast to the wonderful Jane the Virgin however, Narcos is made first and foremost for English speakers. This is evident in the pan-American casting where all kinds of accents, frequently Mexican and surprisingly few Colombian, visit the screen as Colombians. What could be a partly redeeming feature of decent performances is undermined by bad accents, some worse than Keanu Reeves’ British turn in Dracula. In some cases they’re not even trying and in one particularly silly example, a Colombian nicknamed ‘The Mexican’ speaks with an obvious Puerto Rican accent. For an audience reading the middling quality subtitles the various accents are perhaps not an issue. A (possibly) positive result of mediocre translation is that ceaseless Colombian homophobic slang is infrequently translated as homophobic. Sometimes it is made into misogyny, which is a reasonable translation of meaning in some circumstances, and other times ungendered insults but most often it is not translated at all (this will be surprising to some given how much is translated).

The cumulative effect is not so much a bilingual program as an American English one with a preponderance of Spanish(es) in it. It does not help that the script includes groan inducing dialogue such as, “Like Goldilocks he had three options,” and confused phrasings like, “Escobar hadn’t built himself a prison at all. He’d built himself a fortress. But no matter how you decorate it, a cage is still a cage.” Nor that many characters are so shallowly drawn as to be two dimensional. The wide-eyed innocent plane bomber, for example, is less a character than baby-like naiveté given an adult body.

Empire’s Narrator

“Sometimes bad guys do good things” the narrator (Murphy) says in reference to mass executions of drug dealers carried out by Chilean dictator Pinochet. In what ethical universe are mass executions ok? In addition to the ‘heroic’ mass executions, the show doesn’t pause to reflect on the tremendous body count the DEA is directly and indirectly racking up in Colombia. All this is narrated with the ultimate hipster voiceover: an omniscient semi-folksy white guy with a ‘cynical above it all’ cadence that in the end is still deeply dedicated to hegemonic narratives. It sounds like nothing so much as Ray Liotta’s Goodfellas voiceover if it was instead narrated by one of the cops.

Narcos lays on thick an orientalist narrative of Colombia. The following exemplars all come from the shitty, ceaseless voiceover:

- “And the best smugglers in the world were in Colombia”

- “Emeralds are a pretty rough trade even by Colombian standards. If you make it to the top it means you’ve killed your enemies…and sometimes your partners.”

- “The problem was Colombia itself. It was too small a country for a fortune that big.”

- “A drug dealer running for president, it’s crazy right? Well not in Colombia.”

- “There’s a reason magical realism was born in Colombia: It’s a country where dreams and reality are conflated, where in their heads people fly as high as Icarus.”

- “But in Colombia, when money is involved, blood inevitably flows.”

- “In Colombia, nothing goes down the way you think it will.”

Narcos narrates Colombia with explicit, condescending racism and is just as racist in its brief forays narrating the United States, albeit implicitly. The narrator asserts, “Back then [1979] Miami was a paradise.” For whom? Not for working class Black people, Haitians, Cubans, Jamaicans and Puerto Ricans. Equally absurd are declarations about U.S. prisons. Peña and Murphy aspire to have the various narcos extradited to the U.S. to rot in jail there. “Back home it was a whole different deal. Seventh richest man in the world? No one gives a shit. You still get a 6 x 8 cell like every other loser.” This bizarrely idealistic view of the carceral state, carceral empire really, is at complete odds with the supposedly worldly narration and reality. It shows how the narrator’s supposed cynicism about the status quo is actually deployed to affirm its mythos.

Racist and imperialist logics are normative throughout the story. Modest assertions of Colombian prerogatives are met with condescension and arrogance by the DEA agents and narrator. When Colombia temporarily suspends one kind of U.S. surveillance in Colombia the narrator declares, “We sat on the sidelines, hands tied by bureaucracy.”

What the writers show as necessary and virtuous furthers this. Agent Murphy heroically steals a Colombian baby and heroically interrogates a man by putting a gun in his mouth. The U.S. military engages in positively portrayed torture and constant interference in Colombian affairs is portrayed as a good thing.

Gangster capitalism vs. the Neoliberal capitalist state

Narcos posits narcotraficantes buying off Colombian politicians and bribing/sponsoring police forces as abnormal and corrupting when the real history of Colombian politics mirrors that of all capitalist states; the politicians are bought off by capital interests approved by the state. In the U.S. example this is called ‘campaign donations’, ‘lobbying trips’ and ‘corporate sponsorship’. Corruption is thus not the buying of politicians and media — corruption is (literal) gangster capitalists doing the buying. Alternately put, the gangster capitalists’ crime is trying to buy wholesale something that was already bought by the oligarchy. The closest Narcos comes to realizing this is when Escobar’s forces, in an attempt to sway policy, begin kidnapping the children of the rich and famous to replace the prior tactic of public bombings.

Narcos shares this analysis with the The Wire. When Lester Freamon follows the Barksdale outfit’s money through to lawyers and developers making campaign donations the problem identified is not that capitalists are buying policy and favor but that it is drug money used for the buying. Thus pharmaceutical companies producing legal addictive opiates and stimulants can give campaign donations and support police projects that purveyors of criminalized opiates and stimulants cannot. This isn’t just a case of missing the forest (capitalism) for the trees (the drug trade). The creators evidence no knowledge of forest or tree. Judging by the finished product their main source of analysis for the politics of narcotrafficking and counternarcotics is the same as their source for magical realism: the introductory paragraphs of a Wikipedia article.

All this supposedly has something to do with magical realism. It does not. There is nothing magical or fantastic about any of it. The writers mean surrealism but do not know it and that would still be a stretch as narcotrafficking is quite logical in its operations. Formal and informal capitalist markets have tremendous political consequences and frequently astonishing body counts. Hard, cruel logic is not surreal and certainly not magical. Only through a rigidly orthodox discourse of the capitalist state could informal markets seem surreal or magical.

In the end Narcos has some tremendous performances and terrific production value, all in the service of poorly drawn characters, bad dialogue from cliché scripts and imperialist politics. It is a well polished turd that mangles Colombian history and dialects and embraces racism and imperialism. In this way Narcos reminds me less of other televisions shows and more of Kermit Roosevelt and Larry Devlin’s autobiographical writings about their time with the CIA in Iran and the Congo. They narrate cynical, realpolitik histories where yeah, maybe a couple of things could’ve been done better, but the cause was just and their hands were clean. Narcos narrates the DEA and US military in Colombia this same nasty way and it leaves a bad taste made worse when combined with a crap story. A good cast, fascinating topic, high budget and fine production value should go a long way but Narcos only in brief moments rises to mediocrity and all the cocaine in the world couldn’t save it.