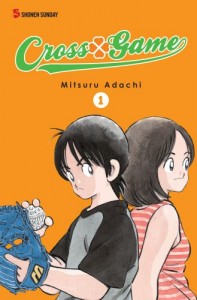

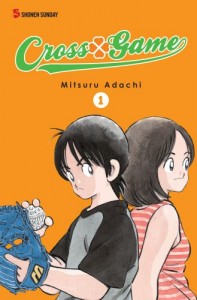

In October Viz released almost 600 pages of comics by one of my favorite cartoonists, Mitsuru Adachi, in the form of the first volume of Cross Game, a series from 2005. In honor of Adachi finally getting something else in print, and in the interest of hopefully furthering the recent discussion of genre, “Comics”, and “Art”, I’d like to share a few thoughts I had upon reading the volume.

But first, a quote! Yesterday on HU Jason Overby had a post up in which he had this to say about the changing face of comics history –

It brings up a good point about how arbitrary “comics history” is. It’s easy to see that positive associations, as opposed to some more objective system of value, are what impel bloggers (critics?) to write about Kirby or King more than Toriyama or Baldessari.

This point applies even more so to creators who have never had their work officially represented in English, or have only had released a small, unrepresentative portion of their total output. What is the history of comics, when critical figures who influenced huge swaths of the work that is available have none of their own work available to an English-speaking audience?

This is the case for Mitsuru Adachi, a cartoonist who made his debut more than forty years ago and who, on a global level, rivals Rumiko Takahashi for popularity and acclaim.

Although Adachi was fairly well-known among the anime and manga communities of the eighties and early nineties, thanks to fan translations of an anime adaptation of his first major manga series, Touch, he’s had a sparse history of official releases in English. His official English debut came in 1999 in the pages of Animerica Extra with Short Program, a series of short stories connected only by their generally melancholic tone, lively drawing, and gentle, deft characterization. The serialization in Animerica Extra continued for two years, generating enough material to be included in two collected volumes, one released in 2000, followed four years later by volume two. For a major creator known for his slow-spooling multi-volume stories, this was a strange state of affairs.

My best guess is that the Short Program releases were meant to test the waters and gauge the potential audience for Adachi in America. And although I personally think Adachi is one of the world’s greatest living cartoonists, it’s easy to see why Viz would be nervous about rolling out one of his major series. They are some of the same reasons that have prevented a wide swath of Japanese comics history from making its way into English.

For one, American anime fans still drive a large part of the market, as companies bank on the synergistic marketing opportunities available from manga series that also exist in other media. And although Adachi had two full-length anime adaptations in the eighties, the American anime fan culture has a very fickle relationship with surface style. In other words, any potential spin-offs (until the recent Cross Game anime adaptation) exist in a form that might seem outdated to the bulk of the anime fan community.

The second, and probably more significant point, is the matter of genre. All of Adachi’s major series (including Touch, Slow Step, H2, Katsu!, and the recently released Cross Game) could be most easily slotted in the category of “sports comics,” although I’ve seen the label “romantic comedy” attached to his comics as well. With the exception of some very popular young adult sports fiction in the fifties and sixties, there’s not a very long tradition of sports fiction in America, and certainly little to no tradition of sports comics. In the eyes of many marketing strategists, a general audience uses a genre label as an aid to enter the story, a convenient short hand that serves as a hook on which to hang the other elements of the story. How do you sell a piece of fiction that most easily fits into a genre that doesn’t exist for its target audience?

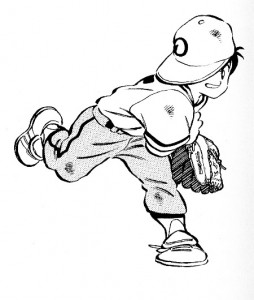

- from Cross Game volume 1

Well, one way would be to try to create the market- to sell Adachi’s work to baseball fans. As a former baseball fanatic myself, I think Viz could very well do so with that kind of strategy. But in trying to sell Adachi’s work to the comics market, and therefore to comics reviewers and critics as well, there’s an additional challenge- that for certain types of critics working within genres can carry a whole host of other negative connotations.

I find it very illuminating to observe the purposeful way that Vertical has marketed Osamu Tezuka’s work in the past few years. They’ve been very careful to package and design the books in ways that echo much of the aesthetic of English independent comics, including employing well-known designer Chip Kidd for many of the early books, and continuing the overtly modern and fragmentary designs with the more recent work by in-house Vertical designer Peter Mendelsund. Looking at the exterior of books like Dororo or Black Jack, would you have any idea that these series fit squarely within swordplay and medical drama genres?

However, like most excellent genre fiction, Dororo and Black Jack play with the genres involved rather than being subsumed by them. This is the case with the work of Adachi as well. Cross Game is “sports comics” in the sense that the characters at the heart of the story love baseball, and playing it becomes a focus for much of their activity. But saying that “Touch” or “Cross Game” are about baseball is like saying that “Les Miserable” is about prison and sweeping and street fighting.

The first three volumes of Cross Game came out in October in one 576 page package. And how are they pitching it? As a tie-in to the spin-off anime, and as a “poignant coming-of-age story,” which, as far as marketing pitches go, isn’t half bad, as both elements happen to be true. They’ve minimized the baseball references in the description and press releases, and have centered around the relationships at the heart of the story, as well as attempting to capitalize on Adachi’s Japanese fame and reputation.

from Cross Game

And it probably has a chance of succeeding. Cross Game itself, or at least the three volumes represented in the recent Viz release, has all of the elements associated with classic Adachi series- clear and confident drawing with very smooth, natural storytelling, slow-moving plots that suddenly veer into unexpected and unpredictable territory, breezy dialogue, and melancholic, sometimes unmotivated young characters whose decisions are often surprising but are never inexplicable.

And yet it may be too genre bound, and maybe too casual, to be taken seriously by many critics. Present in the series are several stylistic choices that could be disconcerting for an audience unaccustomed to them. These include Adachi himself appearing in throw-away panels to mock his own work, background characters pitching other Adachi series to the reader, and a tendency to occasionally veer into cliché. Fortunately these clichéd situations are usually minor detours from the main plot, and seem to be the result of the unrelenting workload of weekly serialization. (Another possibly undesirable byproduct of this pace is the sometimes workmanlike background artwork, which occasionally takes stylistic detours from the figures, which are always confidently delineated.)

Last week Noah generated some heated feedback when he suggested that the manga community engages in a lot more reviewing than criticism, and that books like a Drunken Dream which “despite its genre links, doesn’t fit easily into current marketing demographics,” will have a hard time going without some in-depth criticism to create context for the work. As I mentioned in the comments section, regardless of how you might feel about the “review” versus “criticism” premise, Hagio and Adachi might be in the same boat. They’re sitting on many of those same lines of division.

Well, Noah, I’d like to respond to your post by urging interested readers to BUY! a copy of Cross Game. And cross your fingers that, one day, Touch will be available in English.

And critics, wherever you are? Try to go easy on Mr. Adachi, won’t you? It is just a baseball comic, after all!

(Someone once told me that sarcasm doesn’t come across well in print.)