In the beginning, R. Crumb created comics. I didn’t know this was the Word until I went to the Comics: Philosophy & Practice conference in 2012. I just sort of assumed that Art Spiegelman had created comics. Now I know that’s just in academia.

That conference was enormously interesting, but two things particularly stood out to me. The first was that Spiegelman, who was billed as the keynote speaker, transformed his speech into a dialogue with a prominent professor of media. “This was going to be a talk by me but I was too daunted by the audience of fifteen or sixteen peers who were billed as being here with me,” he said. “I couldn’t make myself deliver something that’s called a keynote address.” This was clearly a last-minute change; it wasn’t noted in the program.

Perhaps Spiegelman was just being modest, but on another level, he was absolutely correct: he was not the leader in that room. Over the course of that weekend, it wasn’t Spiegelman’s name that I heard praised again and again and again; it was Crumb’s. It was almost as though people took turns speaking to his influence. As thoughtful artists like Joe Sacco and Alison Bechdel paid him eloquent tribute, Crumb shouted stray observations from the audience like someone’s drunken uncle. I idly wondered if he was dying.

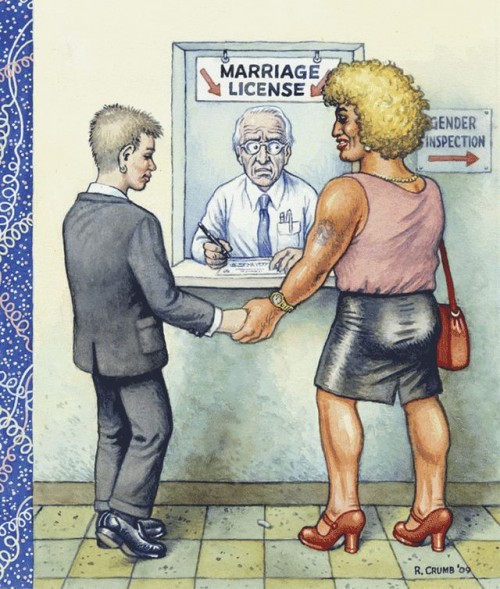

The second interesting thing was a disagreement that Crumb had with Françoise Mouly about his blown cover for The New Yorker. Mouly explained why the magazine rejected the art: it felt out of touch. But this is not the critique that Crumb heard; he preferred to cast himself as a provocateur. “I just realized that you have this loyal readership there that is pretty fucking square,” he said. “When you work for The New Yorker…you have to kind of bend whatever lurid qualities your work might have to fit that sort of lite, L-I-T-E [mentality].”

Characteristically, he was a real jerk about it. But what was most fascinating to me in looking at the cover (which Mouly had projected onto a huge screen) was that it was totally dumb. It had the unique distinction of being heavy-handed without actually making much sense—exactly the kind of “political” work you might expect from an artist who built an empire on drawing his dick.

It’s one thing to feel agnostic towards other people’s god; it’s quite another to find him ridiculous. Crumb’s affectations, his attitude towards women, his dim take on race—I don’t intend to spend a single second of this wild and precious life trying to figure out what other people see in that. Does that mean I’ll never understand comics? The answer is, simply, I don’t care, but I worry that’s arrogant. And on another level still, I feel resentful of that worry.

I find that writing, like life, is a delicate balance of feeling worried and giving zero fucks.

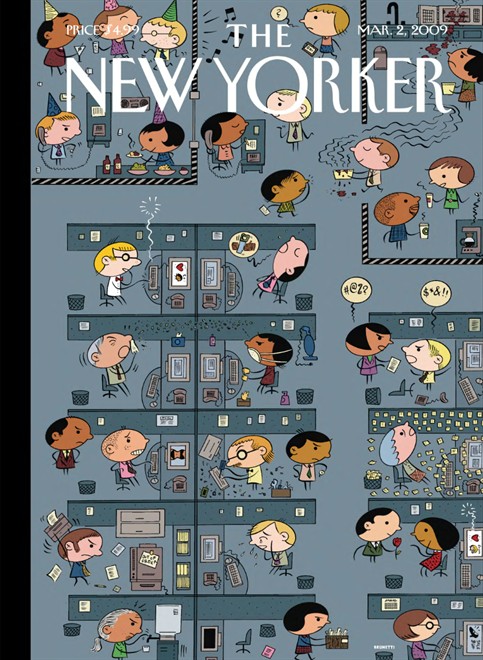

I like paradox. It’s the engine that powers everything interesting. When I started reading comics in a critical capacity, I was startled by the early work of Ivan Brunetti, whose illustrations I had seen in The New Yorker and Real Simple for many years. I hated Misery Loves Comedy. It was nothing like his work I knew and loved. But knowing the same man drew all of those things made me feel very hopeful about the world, where all too often people are afraid to embrace multiplicity. Now I scan every issue of Real Simple hopefully for allusions to murder-suicide. This brings me great joy.

There is a certain type of discourse—or is it a pedigree?—that is highly valued in comics crit. Names of the founding fathers (and let’s face it: it’s always the fathers) are whispered with reverence as a sort of password into that clubhouse. There is also a tendency to value historical perspective over any discussion of the present. Creating a false opposition between then and now (or high and low or this and that) is often done in the name of historical preservation, but it’s always a matter of propagating an opinion. There is no such thing as objective criticism; it is always an extension of the self and what you care about. There is an important distinction between saying these are the things that matter and saying these are the things that matter to me.

Still, some take a cold approach. They equate getting good with growing calloused. They forget that sensitivity is a tool, not a flaw. Men who learn to use that tool are generally praised. Sensitive women are crazy or inexperienced. We’re confused. We OVERREACT. Or so we’re told.

When I wrote the Piece that Shall Remain Nameless, I knew I’d be told all of those things. I felt a lot of doubt. I knew it would take fire that was far more intentional than the smoke the piece itself described. I thought that speaking up was the right thing to do. Now I’m not sure. I never am.

(I give zero fucks. I give zero fucks.)

I closely read a very small amount of material, not because it was in itself momentous, or to catch anyone in a word trap, but to explain how I felt about it, and also how I felt about something larger. The feelings were instantaneous when I read the material; the close reading came later. In response, people closely read my writing back to me. They called it fair, but I would argue it was not in the same spirit as the one in which I approached the project. So it goes.

There’s no one path to understanding. We go about it in different ways, if we go about it at all. In examining an issue from different points of view, it’s necessary to be critical of another vantage. But it’s equally necessary to interrogate your own.

R. Crumb created comics, and it seems to me that comics crit was then made in his image. I see his bad attitude and rude behavior all over this town. I see his petulance and his defensive posturing. I see his unwillingness to absorb a critique. And I also see his growing irrelevance—perhaps most keenly every time another fanboy tries to foist his opinion on the world under the noble guise of History.

Real criticism thrives in doubt, not in certainty. In conversations about comics, there is no right and wrong. There is only coming correct. Under the rock of my lousy long essay, it seems to me that a few people tried. Many others came to conquer. The anxiety of it, as ever, is women’s work.