Last week, halfway through a vacation where I spent a disproportionate amount of time worrying about being mauled by a shark, another white shooter opened fire some 200 miles down the coast. During the manhunt, I watched helicopters thunder up and down the shore searching, not for Dylann Roof, but for a threat so rare as to be almost illusory. In all this, I know, there is a parable for whiteness and its absurd preoccupations in the face of great privilege. Its self-obsessed imagination. My unearned oblivion.

Still, there are things that I know. Having spent the first 18 years of my life in the mountains of Tennessee, and another four in North Carolina, I felt sick, but not quite surprised, when I heard that a white supremacist with a goddamn bowl cut murdered nine African Americans at a historic church in Charleston. Right now the press is doing what it does, trying to play up this white terrorist’s personhood. (Did you know that his poor sister had to cancel her wedding?) The awful truth is that he is like us, just not in the sense such manipulations imply. For years, Roof has been spewing poisonous nightmare views that the people around him didn’t identify as extreme. And why would they? Frankly I’d be hard-pressed to differentiate between sizeable chunks of Roof’s manifesto and certain Facebook posts by my high school acquaintances. His thoughts on, say, George Zimmerman sound a lot like my uncle’s. The difference is that Roof’s rant has the gravitas we are forced to give someone who has murdered nine people. All too often we try to laugh off the words of regular old non-murderous racists, or just live with them, however uneasily.

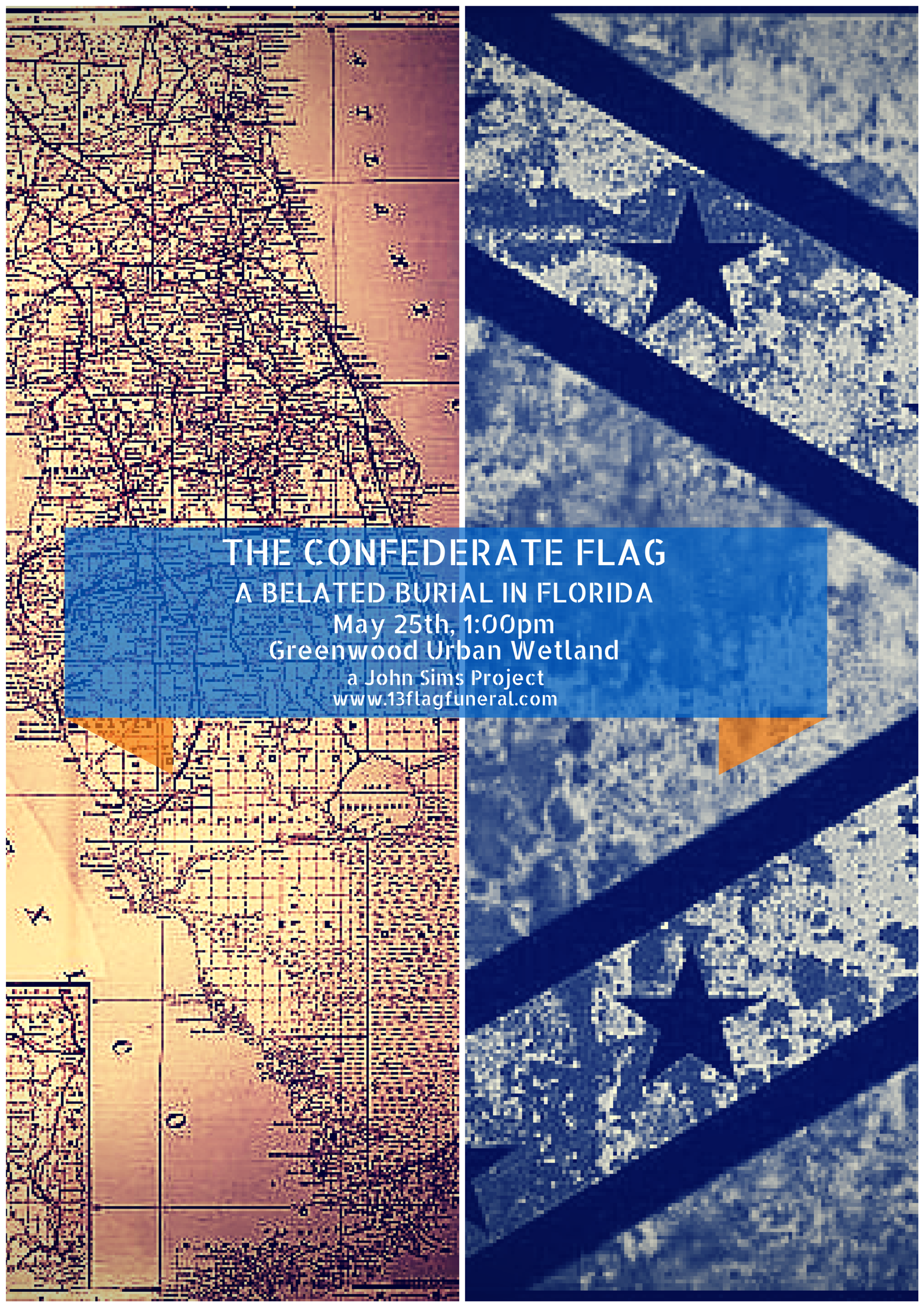

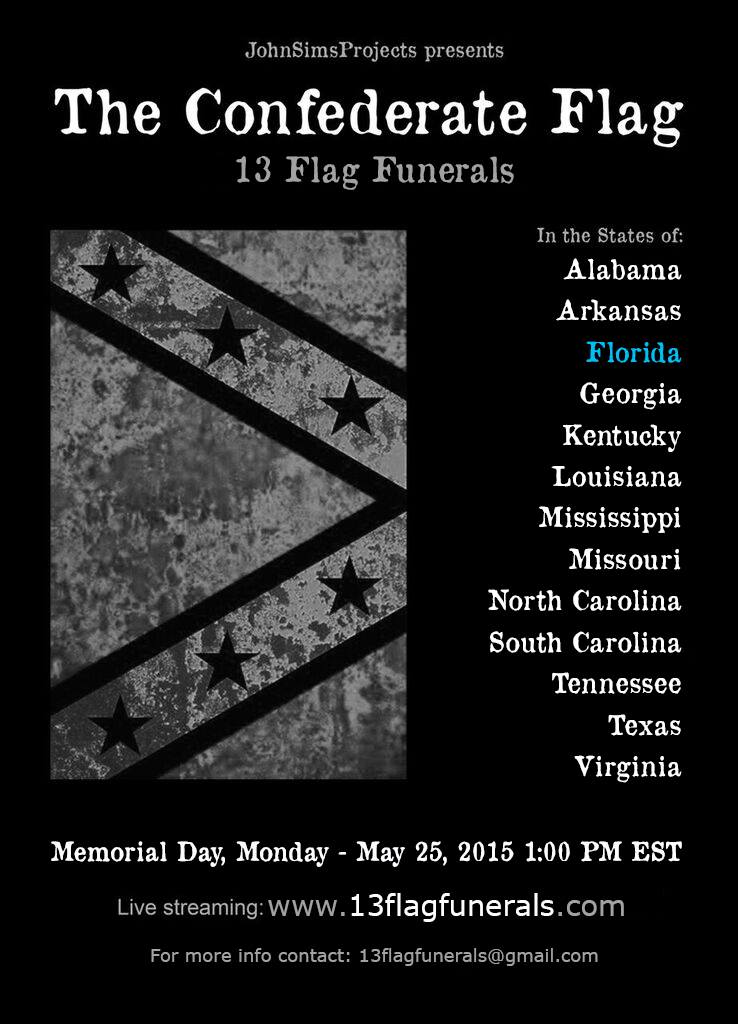

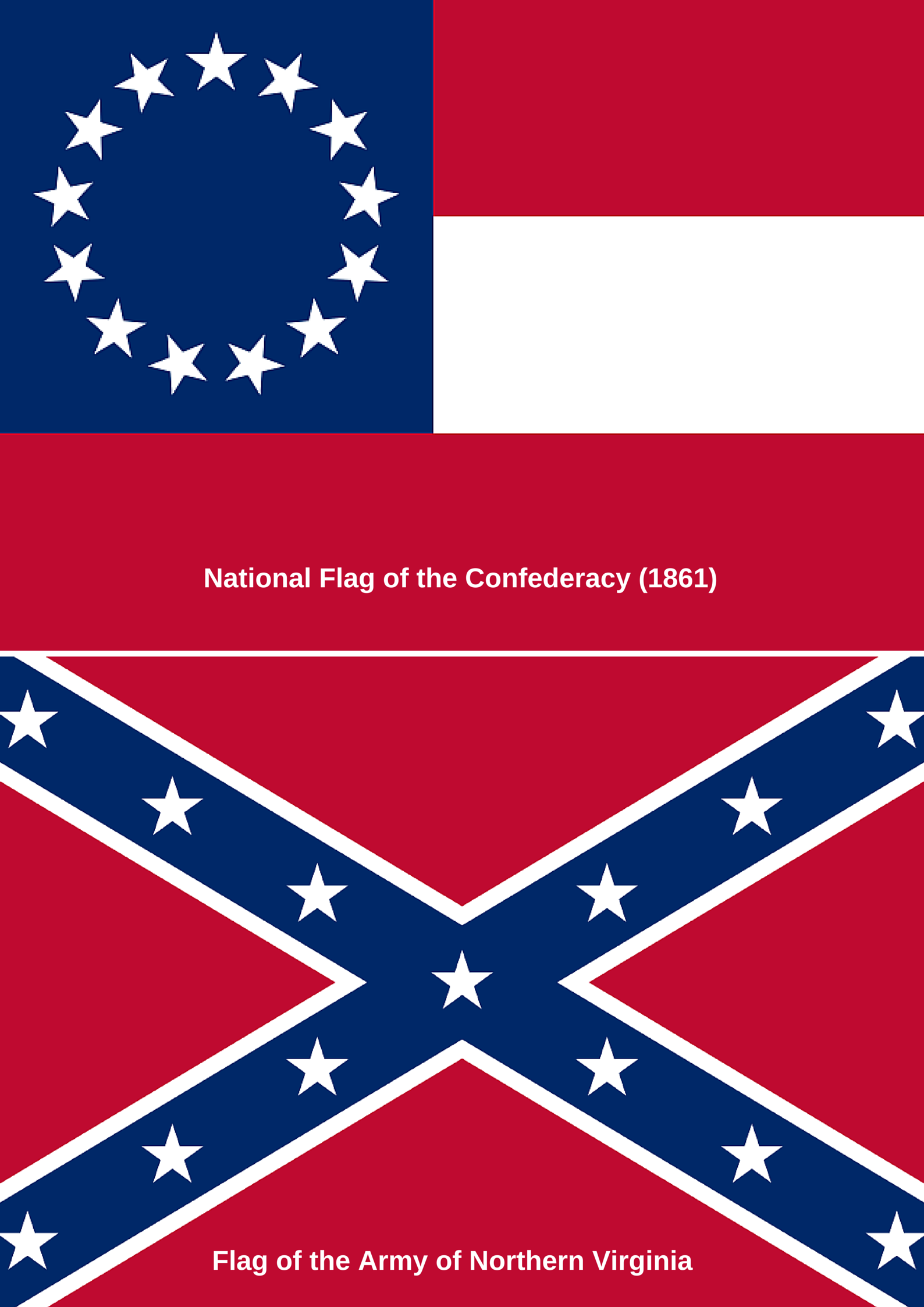

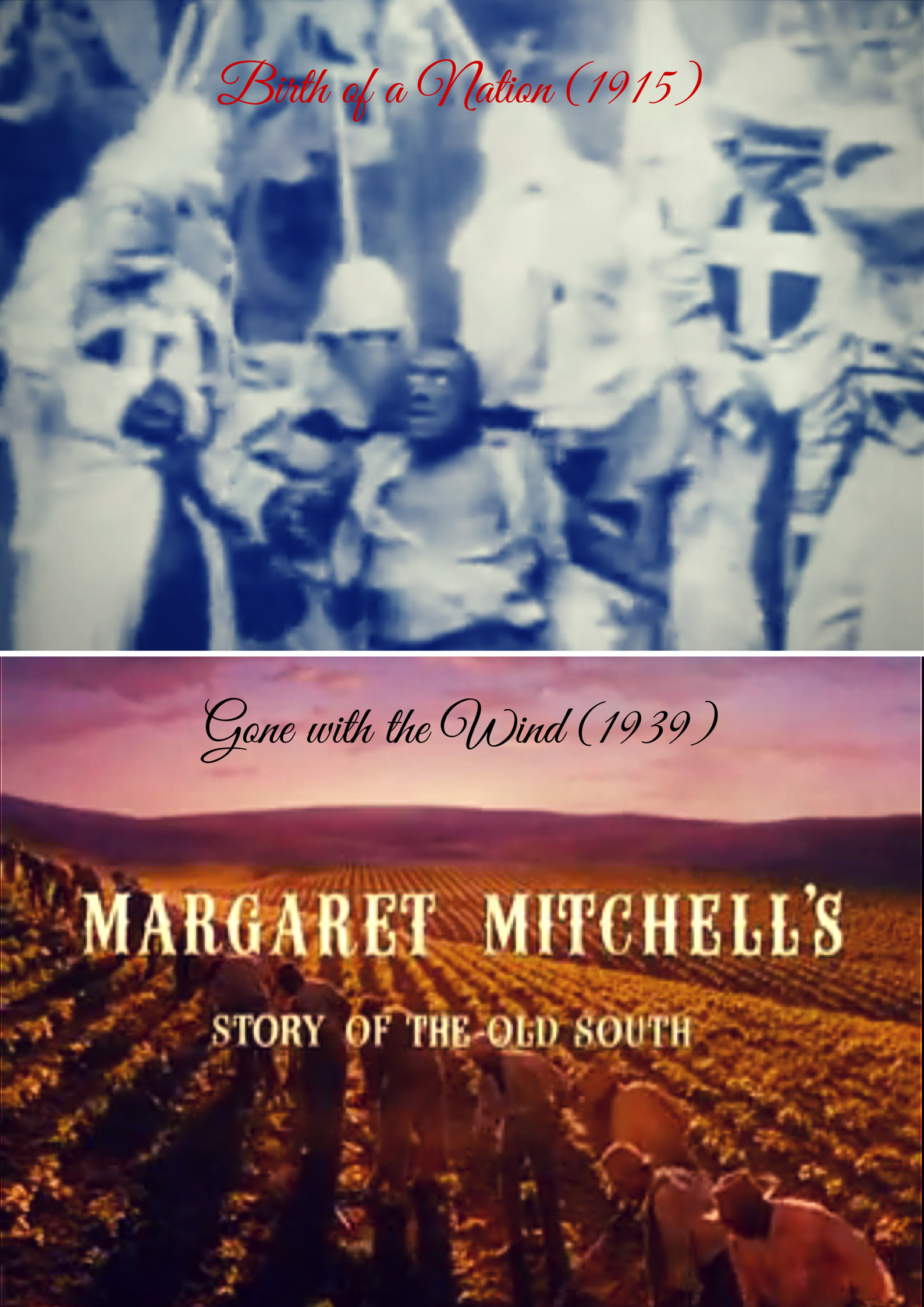

Now that the Confederate flag has been denounced by the likes of Mitt Romney, Jeb Bush, and Walmart, it seems that mainstream society finally recognizes this relic of our shameful past as racist imagery. I’m less sure that people understand that it is much more than just a symbol; it is also a threat. Though I spent more than half my life in the South, I find it difficult to articulate the ways in which its discourse is not just a code, but codes built upon codes, including syrupy insults and thinly veiled warnings. Depending on which side of the law you ascribe to, the Confederate flag carries the implication of violence or a promise to look the other way. Whether it’s draped in the back window of a pickup or waving over a courthouse, its message to black Americans is always the same: if I see you here, there will be trouble.

The rhetoric used by staunch defenders of the Confederate flag will sound familiar to anyone aware of the cultural conversation surrounding satire in comics. In both, you’ll see people rally behind racist imagery under the pretense of honoring history or supporting freedom of speech. Comics figureheads like Art Spiegelman who have no love for white supremacy per se have created and/or defended racist cartoons as though the integrity of art itself depends on it. Not realizing that literally no one self-identifies as racist, they imagine themselves to be that other R word: righteous. What would Dylann Roof make of “Notes from a First Amendment Fundamentalist,” I wonder? Compare Spiegelman’s condemnation of the “sanctimonious PC police” with the part of Roof’s manifesto that talks about how easily black people are offended. Yeah, I know there are differences. But tell me, what similarities do you see?

The Charlie Hebdo shooting was both an international headline and a story deeply felt on a personal level by many people in the comics community. What happened in Paris was a tragedy, and there’s no shame in being moved by a story that is especially relevant to your life. But those who said “Je Suis Charlie” (or, worse, “Cartoonists’ Lives Matter”) did not speak for Comics. They spoke for white people who understood the massacre to be of universal significance because the killers were militant Muslims and most of the slain were white. While this fits conveniently with our idea of Trouble in a post-September 11th world, the incident was, demographically speaking, a statistical anomaly. Very few victims of terrorists—including the state-sponsored ones that infiltrate U.S. police—are white. You know who is? Right-wing terrorists like Dylann Roof, who are twice as lethal as their Muslim counterparts in America.

Reader, I don’t wish to suggest that you don’t feel the appropriate degree of sadness or outrage or abject depression about what happened in Charleston. None of us has near enough feelings for the nine people who died there, much less the victims of other atrocities that happen around the world on a given day. But if you do not recognize the Charleston massacre as a story that pertains to Charlie Hebdo or to comics on multiple levels, you are egregiously mistaken.

As a white person, I’ll never fully understand, much less convey, what it feels like to casually encounter racist imagery like some of the more infamous Charlie Hebdo covers or the Confederate flag. I can only offer an imperfect analogy. Back in North Carolina, across the street from the house where I was staying, there was a bar with a BITCH PARKING sign out front. I wasn’t particularly alarmed or surprised upon encountering it. Had I not lived outside the South for so long, I doubt I would have even registered it as a thing. First and foremost I recognized it as a stupid joke (though of course a joke, like “celebrating heritage” or satire, offers a certain kind of cover or deniability). In its sheer ridiculousness, this joke made me laugh. On another level, I felt annoyed. On another level still I felt weary. And finally, churning beneath all of those things, I felt a sense of unease. To me BITCH PARKING communicated a warning so obvious it may as well have been in flashing lights: Go home, girl. There is nothing for you here.

It was lunchtime and we weren’t there to drink. We didn’t even sit down. My brother-in-law just wanted to buy an ironic t-shirt. Still, looking around that dark room with a handful of Bubbas and a specials list featuring something called the Wet Pussy, I understood that my instinct in the parking lot had been correct. As my brother-in-law cheerfully chose his shirt, I felt something that wasn’t fear or danger or even anxiety, but its nebulous possibility.

Art Spiegelman’s blown cover for the New Statesman reminds me a lot of BITCH PARKING. The comics clubhouse scene is no longer about who’s allowed in; it’s about who feels welcomed. It’s about subtle signs and signals such as who is being tortured in the posters you hang on the wall. The flag you choose to fly.

Often, I think about the bathos with which champion of free speech and New Statesman cover boy Neil Gaiman imagined his own death at the hands of Muslim terrorists when he attended a literary gala at the Museum of Natural History:

Hanging above us as we eat is a life-size fibreglass blue whale. If terrorist cells behaved like the ones in the movies, I think, they would already have packed the hollow inside of the blue whale with explosives, leading to an exciting third-act battle sequence on top of the blue whale between our hero and the people trying to set off the bomb. And if that whale explodes, I realise, even an oversized flak jacket worn over a dinner jacket could not protect me.

To fantasize about your own grandiose, unlikely death is a luxury of whiteness. Back on the coast of North Carolina, I bobbed along nervously in the Atlantic Ocean every day for a week without seeing a single shark. One thing I saw plenty was the Confederate flag, both on the news and waving proudly in front of the shop that sells $7 towels. In comics I routinely see people hold up similar racist images as unassailable paragons of free speech. The next time you’re tempted to mock and dismiss those who tell you they perceive that phenomenon as an act of hostility, know this: the so-called PC police can’t do violence to comics by simply voicing dissatisfaction with this state of affairs. What sort of violence your gleeful disdain can do to them—the humans, not the comics—remains a live question. Whether or not you deign to examine it is, as ever, your choice.