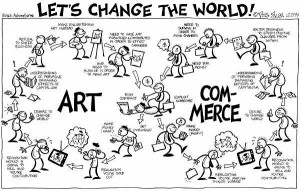

A lot of artists I know sang the praises of David Lowery’s recent post in response to NPR blogger Emily White because they agree with what they see as Lowery’s morality – the importance of the idea that creative work is valuable and worthwhile and worth paying for, not just a side product to lure advertisers or some sort of cultural spirit that doesn’t belong to anybody and longs to be free. Lowery’s post was validating, and people felt that he was sticking up for them and speaking out for their interests. A lot of people in the music industry came out against Lowery’s analysis, but there was still a strikingly strong outpouring of support for the simplicity of his argument and his willingness to stick up for a morality in the artists’ interest.

I agree — that morality should be incontrovertible. Cultural creative work is work; it is valuable; it deserves generous compensation and respect. It should not be stolen by consumers and neither artists nor their work should be exploited by other entities in the production and distribution chain. Encouraging people not to steal is a good thing now just like it’s always been a good thing, and firing back sharply at anybody who denigrates creative work is even better.

But the challenges facing artists in the digital economy require extremely informed, eloquent advocates who can go beyond emotional validation and imagine creative new solutions to the complicated new context in which artists work. Lowery is not that advocate. He’s not even a particularly good spokesperson for this constellation of moral ideas, because being a spokesperson for a morality is about convincing people to change. Lowery’s post, and the comments he’s made on this topic previously, are neither persuasive nor effective because the them/us quality to his rhetoric results in a patronizing superiority that’s nothing more than moral shaming. That’s more the language of clashing subcultures, cliquish sectarianism and bad parenting than it is the language of advocacy, moral persuasion, and cultural change. It’s as if Lowery was put-off by the tone of the tech subculture and those damn kids on his lawn, and allowed that feeling to blind him to how much the arts and technology “subcultures” have in common, in general and on these issues in particular.

Strange and Insidious Bedfellows

In the process of rejecting those shared interests with the tech world, Lowery — probably inadvertently — builds common cause with people and individuals (and even nation-states) who advocate different insidious forms of immorality, ones much more harmful to artists in the long term: violations of civil liberties, violations of privacy, and the subjugation of the interests and voices of individuals to the interests and voices of corporations and state power.

This week’s news gives a good example of what happens when artists take the wrong side: last week, the European Parliament rejected the Anti-Counterfeiting Trade Agreement, ACTA, by a decisive vote of 478/39. The United States signed ACTA in October of 2011, and the EU trade representatives supported the agreement as well – but the EU required it be ratified by Parliament, and this week that ratification failed.

Why did it fail? Despite widespread agreement that international action was necessary to combat international criminal piracy and intellectual property fraud and counterfeiting, the bill contained numerous provisions that targeted individuals and technologies, including ISPs, for criminal prosecution and that, perhaps even more importantly, placed restrictions on the use of legitimately obtained material that are much stricter than those in current international law. The EU’s opposition to the agreement was predicated on these specific concerns:

“On individual criminalisation, the definition of ‘commercial-scale’, the role of internet service providers, and the possible interruption of the transit of generic medicines, your rapporteur maintains doubts that the ACTA text is as precise as is necessary,” (Scottish MEP) David Martin, the rapporteur, wrote in his statement to Parliament (PDF) explaining his recommendation to reject the bill. “The intended benefits of this international agreement are far outweighed by the potential threats to civil liberties.”

Almost all of the identified threats to civil liberties are provisions that grow out of the American model of digital copyright enforcement, promoted by organizations like the MPAA and RIAA and legislated in the Digital Millenium Copyright Act. The DMCA loosely follows what copyright activists call “copyright maximalism” – when digital distribution upended the theretofore “natural” limitations to copyright infringement by eliminating material scarcity, the response of large corporations and governments was to remove pretty much all the existing limitations on copyright enforcement, including any meaningful application of fair use. Maximal enforcement = “copyright maximalism.” Back in the ’90s, when the DMCA was being formulated, Wired magazine didn’t even try to hide their contempt for the principles:

1. Give copyright owners control over every use of copyrighted works in digital form by interpreting existing law as being violated whenever users make even temporary reproductions of works in the random access memory of their computers;

2. Give copyright owners control over every transmission of works in digital form by amending the copyright statute so that digital transmissions will be regarded as distributions of copies to the public;

3. Eliminate fair-use rights whenever a use might be licensed. (The copyright maximalists assert that there is no piece of a copyrighted work small enough that they are uninterested in charging for its use, and no use private enough that they aren’t willing to track it down and charge for it. In this vision of the future, a user who has copied even a paragraph from an electronic journal to share with a friend will be as much a criminal as the person who tampers with an electrical meter at a friend’s house in order to siphon off free electricity. If a few users have to go to jail for copyright offenses, well, that’s a small price to pay to ensure that the population learns new patterns of behavior in the digital age.);

4. Deprive the public of the “first sale” rights it has long enjoyed in the print world (the rights that permit you to redistribute your own copy of a work after the publisher’s first sale of it to you), because the white paper treats electronic forwarding as a violation of both the reproduction and distribution rights of copyright law;

5. Attach copyright management information to digital copies of a work, ensuring that publishers can track every use made of digital copies and trace where each copy resides on the network and what is being done with it at any time;

6. Protect every digital copy of every work technologically (by encryption, for example) and make illegal any attempt to circumvent that protection;

7. Force online service providers to become copyright police, charged with implementing pay-per-use rules. (These providers will be responsible not only for cutting off service to scofflaws but also for reporting copyright crime to the criminal justice authorities);

8. Teach the new copyright rules of the road to children throughout their years at school.

Now, ACTA isn’t merely about enforcment against individual users. It also addressed serious large-scale counterfeiting, something which global trade agencies need tools to deal with. But because the language in the legislation was so slanted toward copyright maximalism – toward protecting the economic interests of rights holders without thought to the expressive interests of individuals, the legislation was seen as threatening civil liberties and conflicting with international and US law, and it failed to pass Parliament.

In a very real sense, this means the agreement is dead. Six of the 8 original signatories would need to ratify it for it to become international law, and this is extremely unlikely to happen given the loss of European support.

In other words, a desperately needed international trade agreement, that diplomats from all over the world spent over a half-decade drafting and promoting, failed because organizations who purport to represent artists insisted that it include inflexible provisions that threatened civil liberties.

What does it mean when artists, through the actions of their representatives on the global stage, are no longer seen as standing on the side of humanity and freedom of expression against exploitation and oppression, but are seen as against civil liberties themselves? What does it mean when artists like David Lowery make arguments that justify and encourage artists to turn a blind eye to these implications and side, instead, with those representatives, the corporations they represent, and their narrow interests?

Why I think David Lowery’s post did more harm than good

In his response to White, Lowery appeals to some very intuitive pro-musician sensibilities, but in the process of outlining those sensibilities and the priorities and moral actions he thinks they should lead to, he makes those musicians into an interest group like every other interest group. This is especially evident in his presentation to the SF Music Tech convention, held earlier this year. It’s a deeply politicized speech that makes explicit that “cliquish sectarianism” I mentioned earlier — his treatment of the tech community in the final section is strident, vitriolic, and divisive in the worst way. Lowery defines his interest group very narrowly and fans the flames of hostility toward anyone who isn’t 100% part of his group.

Yet there are so many stakeholders in this debate who don’t quite fit Lowery’s interest group: people who make obscure kinds of music that record companies never cared about, artists who have had measurable success with Internet business models, people who make forms of art which have never been well served by the “old boss”, people who make technology, entrepreneurs, and a really large variety and range of consumers and expressive individuals. All of those groups have valuable perspectives, ideas, and influence. Consolidation of that grassroots influence is a viable way of fighting entrenched power structures – as my friend Harold Feld says, “policy is not about getting people to do the right thing for the right reasons, it is about getting them to do the right thing for their own reasons.”

The consolidation of influence from the tech and arts communities motivates technological advances with artistic purposes and artistic uses of technology. It spared us some pretty awful legislation when a coalition of artists and technology people defeated the SOPA and PIPA bills. It was important for convincing stores like Amazon to sell DRM-free MP3s that consumers can actually back up and transfer from machine to machine. Finding ways to get artists, the technology sector, and consumers to see each other as compatriots with shared goals is important for making sure everybody’s interests are well served as tech policy around issues important to the arts evolves.

Making musicians into a narrow interest group, oppressed by the “new boss” and at odds with the rest of society (whose world is “made of computers”) is the opposite of the collaborative spirit our current situation calls for. David Lowery is a polemicist, someone who plays to emotions and likes to get people riled up. That’s maybe natural terrain for a songwriter (although not all emotion is polemical), but it’s an abysmal approach for the actual real politics facing artists in the digital economy. His polemic distorts other people’s positions, whether due to passion or ideology, in ways that obscure the full factual landscape, that create rifts between groups who need to be working together and that ossify people’s commitments and vantage points rather than getting everybody informed about the big picture and stimulating imagination across economic sectors. Right now, there’s little more counterproductive than such “partisanship.”

Why I think David Lowery maybe can’t read

Lowery’s response to Emily White emphatically claims a moral high-ground in response to White’s saying she and her generation are unlikely to “ever pay for albums.” Lowery makes an elaborate, and completely accurate, case that stealing music is a bad thing to do, and that all the reasons people usually give to rationalize file sharing are besides the point.

The problem is that almost nothing Lowery says in his incredibly patronizing letter to White has much to do with what White actually said.

Lowery’s letter is a riff. He picks up on that one phrase about not paying for albums — which doesn’t mean won’t pay for music — and improvises for a few dozen measures, making a largely unrelated piece that only vaguely alludes to the original. In jazz, that kid of riffing is how musicians build culture. But in argument, we call it building a strawman. His points are valid on their face, but would have been stronger and more effective – and more ethical – had he cast them in response to examples of people actually saying the things he’s complaining about.

The core issue of White’s post – which was a response to her boss’s post about uploading his entire (legally purchased) record collection into the cloud – was not rationalizing why peer-to-peer file sharing is good or even why it’s ok to get music for free from your friends. White’s point, which almost everybody ignores, is instead that we are in a post-file-sharing world. (Bob Lefsetz describes it by saying that arguing against file sharing is like arguing against a dot matrix printer.)

It’s important that White didn’t file-share to build her collection, and that she didn’t use any of the excuses that Lowery is at pains to debunk in order to defend herself or the ways she did build her collection. She in fact says straight up that both file sharing of copyright material and collecting songs without paying for them are wrong and hurt artists. So in making a strawman out of her, Lowery ends up chastising someone who agrees with him. No good can come of that. People who make strawmen out of other people who already agree with their moral point are not good spokespeople for that moral point.

Why I think David Lowery doesn’t get it

I know a lot of people feel really wronged by the way the digital economy, its stakeholders and its watchdogs, have failed to deal expeditiously and effectively with the very real problems created by changes in manufacturing and distribution structures after widespread digitization, and they want some moral justice as well as real solutions. I understand the desire of artists to emphasize these moral concerns. But Lowery could have written a post focused on morality without also building a strawman, if he were a careful reader interested in a conversation. White’s conclusion isn’t without a moral element — it’s just that the moral element has nothing to do with stealing.

White’s conclusion — her really smart and interesting and provocative conclusion — is basically this: in a post-file-sharing world, large-scale consumer demand for owning media in any form, including CDs, vinyl, paper books, DVDs, even digital files, will be significantly reduced, possibly to the point that demand for owning music or copies of any art no longer exists at all. The collector’s impulse will be transformed (although probably not eradicated) by on-demand delivery and the end of scarcity.

Think about what this means for everybody except the historically minded archivist.

No bins full of CDs or racks of DVDs above the TV.

No overstuffed bookshelves and stacks of books in the corner.

No long boxes.

Not even the massive hard drives full of downloaded songs.

A near-complete dematerialization of reproduced culture.

As the cloud and various on-demand and streaming technologies evolve and mature, White predicts that most people will prefer using them to buying. Her point is basic demand-side economics. Not that people will file-share. Not that some significant percentage of people under, I dunno, 30 years old see nothing wrong with stealing content. But the idea that in the future most people, period, will prefer to buy access to music than the music itself. They will, as with all cloud technologies, begin to consume and interact with art as a service rather than as a product.

It’s provocative, and radical, but it’s not necessarily a bad thing for artists: there are predictions that, once a critical mass of media becomes instantly available on-demand, artists will actually make more over a single listener’s lifetime from that listener streaming their albums over and over than they could possibly ever make from that fan buying the album. Lowery could have grappled with this new way of thinking. He could have questioned whether there are inherent and meaningful moral or ethical problems for artists in legitimate cloud-based business models, and he could have asked what potential new illegitimate uses cloud-based models might give rise to. He could have called attention to the ethical and moral dimensions of artists’ standing in the cloud. Writing about those would still have been a riff, but it would have been a vastly a more honest and productive riff than the one he came up with.

However, I don’t think morality is what’s really at stake here. Those issues need to be framed up in detail – that’s one of the potential good outcomes of a large-scale public conversation – but they’re definitely not simplistically moral like consumer theft, or even the more complex terrain of how to ensure our society values creative work both culturally and economically. More important than morality here is politics: who has control of those “universal databases” White calls for? How fair is the competitive landscape? What are the licensing obstacles? Are there tensions between the existing structures of copyright and adequate compensation based on playcounts? Do the models of ownership and rights holding that have evolved for media, and in particular for software, really work ethically and effectively for creative workers? There are lots of questions about digital distribution – what it even means to “own” a copy of an artwork; whether the use of arts should be and can be subject to the kinds of licensure restrictions placed on software use; when and how fair use applies to creative reuse; the extent to which all the various middlemen, technological and creative, are beneficial to the process or are in the way; whether there are meaningful differences between a personal collection in the cloud and the catalogs of streaming services, what those differences are, and whether they make sense and provide value to the consumer given the relative costs of those models.

Too much emphasis on morality in this particular context creates the illusion that people are more immoral and entitled than they actually are. There are plenty of immoral, entitled people, but there are also a lot of people who prefer paying to file-sharing or file-swapping. Lowery’s post suggests a sort of “demand management through ideology”, direct from the artist to the consumer, where moral shaming performs the economic function of interest rate manipulation or a sin tax, with the idea that if artists say enough times that the old model is better for them people will do the right thing and go back to buying CDs and DVDs and never downloading and minimizing their streaming and supporting the old model of advances recouped through sales. But the take-home is that, even if we set aside the old problems with the old models, even if we discount the damage such a trust deficit would do to the market period, that kind of demand management probably just won’t work.

This is because people who use Spotify and other cloud-based streaming services don’t see a moral difference between the subscription fees they pay and buying a CD, or between the advertising on Spotify and that on network TV. They do, however, see the moral problems with the discrepancy between what they pay for a CD and what the artist gets, and with myriad models which primarily enrich a very inefficient infrastructure of middle-men. And they see practical problems with the choice between paying for a CD without instant delivery versus paying for a digital music file that perhaps has a finite lifespan or at least where they’re responsible for backup, especially when cloud-based subscription services offer them instantaneous access to the same music, and much more music, in a model where the restrictions and inconveniences seem better aligned with the cost model.

When physical albums, CDs or vinyl or whatever, were sold as the standard means of buying music, the cost, and value, of the item was based not only on the unique properties of the intellectual, creative content, but also on the physical materials, and most importantly on the control and access that ownership of the physical media gave the purchaser. Owning your own physical copy was the only way to ensure access to what you wanted to listen to, when you wanted to listen to it. A listener without a copy had to wait until the one or two songs that were going to be played on the radio came on, or they had to listen at a friends’ house. If you wanted full access to the content, and full control over when you heard it, you had to buy your own physical copy of the album.

But after digitization, the benefits of owning the physical media largely evaporated, and the exchange telescoped down to focus just on the value of the creative content itself – something which had always been a blurry and opaque percentage of the cost of the material good. In making the physicality of the product obsolete, digitization also made the packaged information vastly more material and tangible.

It’s often pointed out and absolutely true that there’s no material scarcity associated with digital copying – a digital resource is not a limited resource. But material scarcity isn’t as relevant as many people suggest — it’s vastly more relevant that digitization and computing advances made control and access plentiful. This is true for all culture, not just music: I no longer have to watch the Billy Graham Crusade or the Bob Hope Special right along with the rest of America because there are only three channels; I can go to Netflix on Demand and watch a documentary about Africa or a James Coburn movie and if I am the only person in the world interested in that movie at that exact instant, it’s still available to me. There’s no meaningful difference between accessing that material on demand and owning my own copies.

So even though it’s possible to shame people into a better morality, it is not possible to shame people into treating – and paying for – a plentiful commodity as though it is scarce.

This ties into Lowery’s interesting and valid point that we’re more willing to pay for electronic equipment than we are for content. Electronic equipment, though, is still physical, and subject to scarcity. The cost of commodities is a measure not just of their cost of production but also of their exchange value. In situations where the exchange value is insufficient to cover the cost of production, a commodity that it is possible to produce, might not ever actually be produced. You can increase a commodity’s exchange value by increasing people’s willingness to pay for it in some way, but there’s going to be a limit to how much you can talk people into valuing something when they don’t see a direct benefit to them. You can convince people that it’s immoral to not pay anything for music, because you can show them how that affects production. But you can’t convince people that existing, already recorded music is scarce, expensive to produce, and difficult to distribute – because it isn’t.

Why I think David Lowery is dangerous

Lowery’s unwillingness to distinguish between brute file-sharing of copyright material, which is immoral, and paid services like Spotify, which aren’t, obscured the real issues in White’s post and derailed what started out as a really valuable and much-needed public discussion about the impact of streaming and the cloud on the stop-gap download-driven revenue models that have characterized the digital culture economy up to this point. Ignoring that and driving discussion toward the issue of not paying for music, which nobody was arguing against, allowed Lowery to evade the more difficult issues that require greater imagination. He turned a provocative and forward-looking prompt from NPR into an opportunity to push his backward-looking mantra that the digital economy is bad for artists. And the creative sector, emotionally ginned up, kind of let him get away with it.

That’s short sighted. The digital economy isn’t going away just because David Lowery isn’t pleased with it, as both TechDirt’s Mike Masnick and Merlin CEO Charles Caldas point out in their responses to Lowery (linked below). Realistically, artists just have to deal with the digital economy. Fortunately, it’s still evolving enough that there’s time to make sure that the new business model’s not a disaster. But critical energies can’t get distracted — they have to move from primarily talking about fringe models often used for illegal purposes, like the Pirate Bay and Bit Torrent, to serious discussion of legal services like Netflix streaming and Spotify, because those are the models that increasingly will dominate the market. Most people don’t want to steal music. They just want value for their money and convenience.

This conversation is particularly important for books, more so than for music and DVDs, I think, because books do not yet have any kind of viable, widespread subscription or even library-like models. Almost every single book in print was printed from a digital file, yet most books aren’t even available for purchase as ebooks, let alone available to digitally “rent”, borrow, or browse. Google Books has set a dangerous precedent that books online will be free – a precedent that will only be overcome by a viable cloud-based, on-demand model for “print” media. But the publishing industry appears to still be struggling even just with making books available digitally for purchase. This is way behind the curve, and it needs to be pushed into more innovative directions.

Distracting the Internet from a smart discussion about streaming and the cloud by making the conversation about stealing — as Lowery’s response to Emily White does — does absolutely nothing toward resolving those problem; it only creates a false sense of conflict between the tech community and the arts community that is likely to result in reactionary policy that maintains the worst elements of the status quo.

Links

Original post by NPR’s All Songs Considered host Bob Boilen

Blog response by NPR Intern Emily White

Response to Emily White by David Lowery

Response to David Lowery by Gizmodo and the CEO of global rights agency Merlin, which represents 10,000 independent artists

TechDirt’s summary of articles by musicians who disagree with Lowery’s letter to White

Talk by David Lowery at the San Francisco MusicTech Conference in early 2012

Response to David Lowery’s talk at SFMusic by TechDirt CEO Mike Masnick