This first appeared on Splice Today.

____________

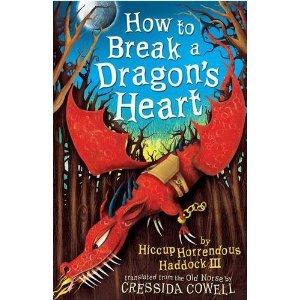

Cressida Cowell’s How to Break a Dragon’s Heart, like all the How To Train Your Dragon series, is told through a frame story. The hero, Hiccup Horatio Haddock III, is an old Viking warrior narrating the story of his adventures as an (insufficiently fierce, overly cerebral) Viking child.

The frame story doesn’t impinge too much on the narrative. It’s even unclear who the old Hiccup is supposed to be talking to…and the bulk of the book is in the third person, not the first, so it’s not like you’re insistently reminded that old Hiccup is doing the talking. Still, in this volume at least, the frame is thematically accented in the book’s creepiest scene. Hiccup has been imprisoned in a hollow tree by his arch-enemy, Alvin the Treacherous. Inside the tree with him, it turns out, is an old witch, who has been in the darkness so long she no longer needs light to see. Hiccup refuses to tell her who he is, and the witch proposes a game. She will tell him a story, and at the end of it, the two of them will try to guess each other’s names. Whoever guesses gets to kill the other. The witch, invisible in the dark, starts to speak with her disembodied voice…and to Hiccup’s horror she tells him the story of his own ancestors. Cowell actually draws in the tree bark as a kind of circular frame of rough blurry bark ringing the dialogue. Thus, in the visible ring the narrative goes round, Hiccup telling the story of the witch telling the story of Hiccup — who guesses the witch’s name just as she guesses his, and so, in a way, manages to tell her story too.

The insistence on the storyness of the story is a staple of much children’s literature, from Alice in Wonderland to the Never-Ending Story. It’s so associated with children’s lit, in fact, that you can sometimes forget that it’s also a solidly modernist obsession, used obsessively by Joseph Conrad, Faulkner, Borges, and others.

Modernists and children’s author use the frame story for similar reasons; it’s self-conscious. It acknowledges that the narrative is a game, which is nice for kids (who like games) and for sophisticated aesthetes (who like games as well.) And, in fact, that sense of playful whimsy, of a story that knows its own storiness, is one of the things I like most about Cowell’s series. Alvin the Treacherous’ constant horrible deaths and miraculous survivals, always returning with one less body part (this time he’s got a wooden nose); or the way the doomed heroic fiancés keep shouting “YOU BETCHA!” or “TOO RIGHT!” no matter how horrible the situation; or even Cowell’s delightfully scratchy, blobby artwork — it all emphasizes the createdness of the characters, they’re existence as cartoon tropes on the page. They aren’t real; they’re in a frame, and the pleasure is less in finding out what happened than in seeing the pieces fit into place, like Hiccup’s miraculous key which gets him out of the tree and frees the fiancés and releases the dragon with the broken heart.

It’s interesting to compare Cowell’s embrace of storytelling with those other more popular fantasy series. Harry Potter and Twilight aren’t any more real than How To Train Your Dragon, obviously…but they’ve both got a more fraught relation with the real. Neither Harry nor Twilight has a frame story…and in fact both are in many ways predicated on denying a frame and pretending that the fantastic is real. In Harry Potter, the world of magic exists unknown side-by-side with the real world, on magical railway platforms halfway between more mundane train stops, or in Quidditch games concealed in farmer’s fields. In Twilight, too, the vampires and werewolves are all around us, but we don’t know — only the reader does. Both series are about secrets and knowing truths. Harry is the Boy Who Survived, defined by his encounter, and escape, from the ultimate reality of death.

Hiccup, on the other hand, is, according to the witch, the “Boy-Who-Never-Should-Have-Been.” Hiccup’s father, it turns out, married the wrong person; prophecies went awry, stories went wrong, and the result was an accident of fate, a hiccup in the narrative. Hiccup isn’t but is, like a character in a book. “The story had done its work. Carried away by its power, Hiccup had betrayed himself and his identity,” Cowell writes. The narrative knows who you are, perhaps, because who you are is nothing but a narrative.

In the first words of the book, which are the first words of the frame, Hiccup says, “History is a ghost story.” In Harry Potter or Twilight, of course, the opposite is true – the ghost story, the magic, and the vampires are history. That’s why those series are replete with angst and darkness; they’re about convincing you they’re real, and the real is trauma. How To Train Your Dragon is much lighter fare; its witches are only voices, and you know they’ll stop when the story does. But what else will stop? If history is a ghost story, who’s telling it ? If there’s a frame, what’s outside it? A secret’s a truth; a story’s a mystery. Harry may have been born for glory, but Hiccup is born for who knows what — his future coming towards him like a ghost, frightening and awkward and indistinct, the story he will be.