So, as some of you probably know, I’m currently working on a Patreon to fund one column a week about topics I can’t get mainstream sites to publish. (The column will be called Twisted Mass of Heterotopia, by the by — or it is called that, since this is the first one!)

This piece is a kind of sample of the sorts of things I might write about. I initially placed it at a lovely little crime fiction site called The Life Sentence. But before it could get published, the site shut down. Because there’s no business model that makes printing things like this affordable.

So, since it was homeless, I figured I would run it here. If you’d like to see essays like this on a regular basis, please consider contributing.

Thanks also to Lisa Levy, my editor, who offered a bunch of suggestions that made the piece better.

__________

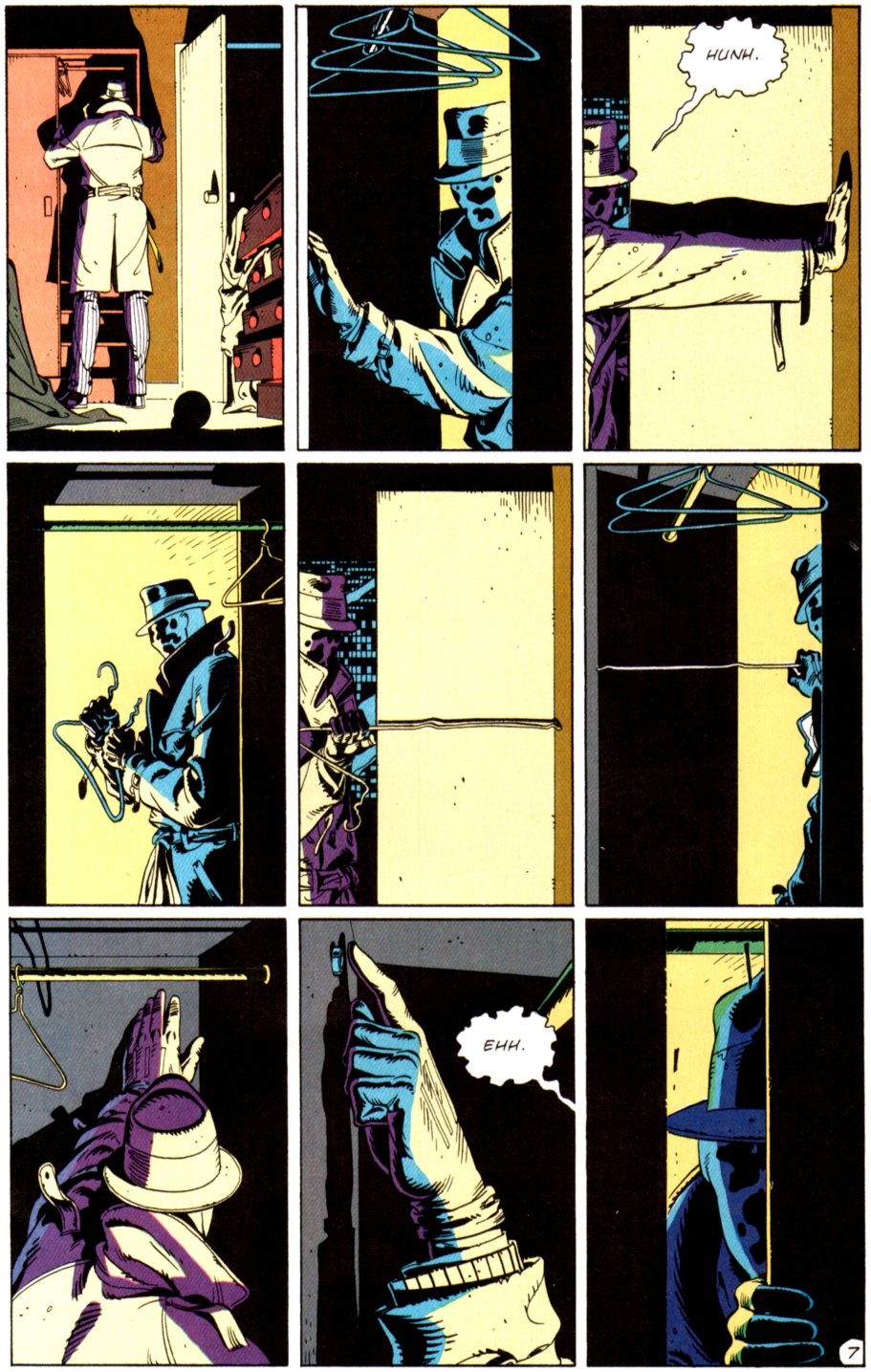

Alan Moore and Dave Gibbon’s 1987 graphic novel Watchmen famously opens with a murder mystery: the Comedian, superhero and government operative, has been thrown to his death from his upper-story apartment. The detective investigating the crime, trench coat and all, is the brutal, deadly superhero Rorschach. After the police leaves he invades the Comedian’s apartment in a grid of light and shadow, his body leached of color as a semi-silhouette against dramatic squares of black and yellow. In this context, Rorschach’s masked face, with its shifting globs of black on white, becomes a genre reference. The superhero’s secret identity in Watchmen is noir — at least until Moore and Gibbons undermine that, as they undermine most everything else.

Watchmen is probably the most critically acclaimed superhero comic ever ;,regularly appearing high up on best of comics lists, and even garnering a spot on Time’s list of 100 Best Novels,. It is perceived as, and presents itself as, serious art . And part of the way that it presents itself as serious art is by using the tropes of tough pulp crime .

Compared to highbrow lit, crime fiction can seem declassé. But superhero comics have long been aimed at children, and have a tradition of whimsical goofiness — Captain Marvel fighting an evil sentient worm, or Wonder Woman bouncing off to the stars on the back of a giant space kangaroo, In comparison, Raymond Chandler and Jim Thompson come across as relatively validating and adult. Crime lends superheroes grit, seriousness, and realism.

And so Rorschach’s origin story involves the true-crime 1964 Kitty Genovese rape . In a case early on in his career Rorschach investigates a child’s murder, and ends up killing her killers in bloody fashion. He later breaks a man’s fingers for information, and tracks down a crime boss in a shadowy prison saturated with enough blood and tough talk to fit neatly into the lineage stretching from Assault on Precinct 13 to Oz.

Watchmen created a whole slew of adult, gritty violent superhero narratives in its wake. One of the most notorious was a 1994 Green Lantern story in which GL”s girlfriend was murdered and stuffed into a refrigerator. Another was the 2004 series Identity Crisis in which Sue Dibny, the wife of that silly character, the Elongated Man, was brutally murdered. These comics were not necessarily highly thought of, but they show the trend towards using crime and pulp violence as a way to signal adult fare, and separate superheroes from their infantile past. There’s nothing like a murdered superspouse to demonstrate that comics aren’t for kids any more.

The most recent high-proifle example of superhero crime as validation is the highly aclaimed Daredevil Netflix series. Daredevil is the most ground-level, grimy, street-level-crime focused Marvel franchise since 1998’s Blade. The series is loosely based on the also much-admired Frank Miller/Dave Mazzucchelli graphic novel Born Again — not so much in its plot as in its vision of Matt Murdock fighting alone against the Kingpin and his tangled web of organized villainy. Daredevil’s origin story (in both comic and television) involves his boxer dad enmeshed in a price- fixing scheme. On Netflix, his first episode battle is against human traffickers. These familiar genre narratives signify realism because they ooze a familiar corruption and sleaze.

The fact that the Kingpin is involved in a complicated gentrification scheme seems like meta-commentary . The upscale skyscraping jauntiness of Iron Man or Thor or even Ant-Man has no place here in these grim, rent-controlled, crime-ridden streets. Daredevil is tougher and truer because he’s fighting street-level dealers and pimps and local-news-headline scum. The hero has supersenses (not very realistic that) but he usually uses them to figure out whether people are lying so he can torture them in classic tough guy style. The interdimensional alien invasion which closes out the Avengers film serves as the backdrop for the Daredevil series — the evil Loki’s monster army destroyed all the buildings that the Kingpin plans to rebuild. But that decidedly un-gritty invasion backstory serves as a foil. Those silly things fly around up there in someone else’s superhero narrative. Here (for the most part) our superpowers are dark, serious, and earth-bound.

An alien of sorts also whooshes in at the conclusion of Watchmen — and not coincidentally, that ending has often been seen as one of the series’ weakest moments. All the grim darkness and dark grimness, and this is the end? Rorschach’s pulp investigation turns out to be a preposterous red herring set up by super-villain/hero Adrian Veidt/Ozymandias. No one was out there murdering superheroes, as Rorschach thought. Instead, it was all a distraction from Veidt’s plan to build a giant Cthulhu-analog complete with broadcasting psychic-brain and explode it in New York, thus uniting the world against the alien invaders. The whole thing is utterly preposterous sci-fi goofiness. And Rorschach, our intrepid detective, is disintegrated by Dr. Manhattan with an energy blast. So much for realism.

I remember reading Watchmen when I was in high school and being hugely disappointed by the goofy conclusion (did I mention Ozymandias catches a bullet? He’s got Tibetan mystical skills or something, so he catches a bullet.). But as I’ve gotten older, I’ve come to appreciate the ruthless silliness with which Moore undercuts his own pulp validation. Rorschach thinks that crime and the brutal law of the streets is reality. As a ground-level detective, he figures that the problems he faces are ground-level problems that he can work out. Solve a murder, find the killer, break a few fingers —maybe it won’t save the world, but it’s doing good by inches in the muck of Real Life.

But what if Real Life isn’t particularly real? What if all that local-news-panic crime doesn’t actually matter? Veidt saves the world in one big rush by dropping a gigantic alien bomb — or possibly he doesn’t save anything, and just kills a whole mess of people, like George Bush rushing into Iraq. Either way, he and his ridiculous megalomaniacal schemes are a lot more real, in the sense of real consequences, than Rorschach wandering around looking for some cape-killer who seems small-scale enough to exist but actually doesn’t. Pulp conspiracy theories are too small; the people at the top have bigger plans. There are supervillains, and they always win. All the time.

Watchmen is often credited with deconstructing, or undermining, superhero tropes — with showing how naive and silly the caped saviors are. That’s a reasonable way to read the comic. But I think, by the end, you could see it not as a deconstruction of supeheroes, but as a way to use superhero tropes to deconstruct, and undermine, the grim gritty myth of pulp noir crime realism. At the end of Watchmen, Rorschach is dead, and the debris and blood is being washed and cleansed away from the New York streets. The future is gleaming and shining and new. and littered with dead bodies. The small scale cop solving just one murder at a time seems almost too cheerful—an exercise in Nostalgia, which, not coincidentally, is the name of the perfume line Ozymandias’ company abandons at the conclusion of the comic. A fake alien is more real in the end than a fake gumshoe. And compared to the machinations of the superpowers, crime looks less like reality, and more like a distraction.

_______

If you’re interested in seeing more columns like this, consider supporting my patreon.