(Honoring online comics criticism written or published in 2012. A call for nominations and submissions.)

Regular readers of The Hooded Utilitarian will remember a semi-annual event celebrating the best online comics criticism. Last year’s survey sank like the Titanic due to sheer lethargy on the part of all involved, most notably myself. For those of us who find it hard to get out of bed for the latest and best comics criticism, allow me to commiserate.

On previous occasions, I would ask the various judges to select quarterly nominations from which the entire group would vote at the end of the calendar year. This proved useful in the sense that it brought in nominations on topics and from sites peripheral to my usual areas of interest, but also limiting in that it was dependent on the variable submissions of the judges for that year. Even worse, when busy lives came to the fore, there were no nominations to be had. Clearly, reading comics criticism can be a tiresome business.

In order to facilitate matters, I’ve decided to take over the nomination process myself and also open it to the HU readership (which I presume is wide enough in its taste). Web editors should feel free to submit work from their own sites. I will screen these recommendations and select those which I feel are the best fit for the list. There will be no automatic inclusions based on these public submissions. Only articles published online for the first time between January 2012 and December 2012 will be considered. I have not selected any articles from the HU site for obvious reasons but invite HU readers (not contributors) to send in their recommendations.

If all goes well, we might actually have a nomination list to vote on at the end of the year. At that point, a small group of jurors will be invited to read the long list of nominees and select the eventual winners.

The following list consists of articles of note and others which I personally find uninteresting but which have attracted considerable notice online. The object of this listing is to be inclusive without excessively compromising quality.

(1) Robert Boyd on Kramers Ergot #8 and the Art School Generation.

(2) Gio Claival on the art and comics of Dino Buzzati.

(3) Craig Fischer on Jiro Taniguchi’s The Walking Man.

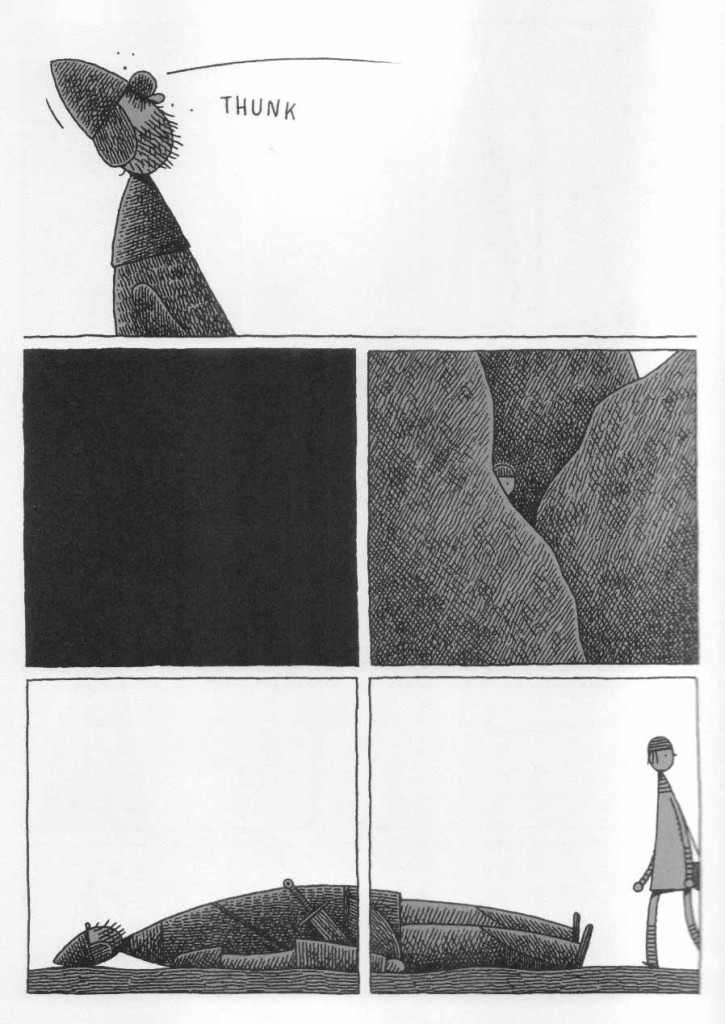

(4) Edward Gauvin on David B.’s The Littlest Pirate King.

(5) Bill Kartalopoulos on Joost Swarte’s Is That All There Is.

(6) China Mieville on Tintin and censorship. I feel compelled to list this here to forestall any complaints of its lack of citation. Mieville’s piece is certainly criticism (about Tintin, racism, and censorship); a breezy, informative and well written article for newbies but of slightly less worth to the average person informed about such matters. In a famine, even the local burger joint looks like haute cuisine.

(7) Amy Poodle on Superhero Horror.

(8) Daisy Rockwell on Craig Thompson’s Habibi. (Full version available at her blog). I have reservations about recommending this review. Lord knows my feelings about Habibi. A truly remarkable review would find a way to make a strong case for the intellectual strength and positive aesthetic value of Habibi. I have yet to read such an article online.

(9) Khursten Santos – The Tale of Three Tezuka Ladies.

(10) Matt Seneca on Guido Crepax’s Valentina.

“There’s a fundamental problem underlying all erotic work done in the comics medium, one even more difficult to get past than the lack of audible sound and visible motion bedeviling the action-oriented material that dominates the form’s American market. How does one create art that reproduces a physical sensation created by bodily contact without being able to reach out and touch one’s audience? It’s the same problem that faces makers of pornography in any medium, but in comics it’s especially difficult.”

Even though the initial premise as stated in the opening paragraph is entirely false — if the difficulties faced by comics pornography were so dire, where would that place the reams of exalted illustrated smut over the centuries — this remains Seneca’s best piece so far this year. The usual Seneca traits of overwhelming love and earnest exaggeration (in this instance Crepax is compared favorably to Herriman, Joyce, and Picasso) are all on display but here sharpened by his obsession with Crepax’s Valentina.

(11) Kelly Thompson (She Has No Head! – No, It’s Not Equal). I’ve put this here because it seems to have found a place in a lot of people’s hearts, not least HU’s own dictator for life. This is a creditable article on that age old issue of women in costumes but somewhat tiresome if one has spent more than a few months reading superhero criticism — the absolute nadir of that cesspit known as comics criticism. If I was judging criticism on the basis of moral virtue, this would probably get top marks but it has little to add to the current thinking about superheroes.

(12) Kristy Valenti on Frank Miller’s Ronin.

(13) At The Comics Grid:

Kathleen Dunley on Ben Katchor and What’s Left Behind.

Nicholas Labarre on Art and Illusion in Blutch’s Mitchum.

Peter Wilkins on Pluto: Robots and Aesthetic Experience

(14) And at TCJ.com:

R. C. Harvey – Johnny Hart to Appear B.C.

Jeet Heer on Gahan Wilson’s Nuts.

Ryan Holmberg on Guns and Butter.

Jog on Franz Kafka’s The Trial: A Graphic Novel.

Bob Levin on Yiddishkeit: Jewish Vernacular & the New Land.

Seth on his work on The Collected Doug Wright.

Matthias Wivel on Donald Duck: Lost in the Andes.

This list is limited by time and my own personal taste and habits. As such, I would encourage HU readers to submit their own recommednations in the comments section of this post. Alternatively I can be reached at suattong at gmail dot com. The lack of manga criticism in this list is particularly telling and I would be grateful to receive potential nominations in this area — reviews or essays which go beyond mere text-image summary or even textural history and which place a work into the context of real world experience and broader aesthetics, writing which pries open the hidden depths of a work

* * *

If the quality of the criticism which an artform attracts provides a glimpse at its health, then surveying the landscape of comics criticism can only be a a sobering experience. The patient while not exactly pallid looks distinctly moribund; sitting idly on the couch shoveling down crisps while shouting epithets at the latest pamphlets.

One is not so much concerned by the proliferation of sites obsessed with the marketing and economics of comics, nor the innumerable sites devoted to the idolization of cartoonists . These will always be with us and may in fact be signs of a healthy fanbase. Rather it is the stagnation of sites and writers devoted to the serious consideration of comics that should be of concern.

This may be best symbolized by the resurrection of TCJ.com – a site which is finally making an earnest attempt to emulate its illustrious print predecessor. The steady flow of interviews, reviews, and long form essays has seen the masses flocking back to the once fallen giant. This is both comforting to its old adherents and yet a standing rebuke suggesting how little has changed in comics criticism since its emergence into adolescence in the 80s and 90s.

The implication here is that the comics world is so bereft of writers of quality and of a pioneering spirit that there remains little room on the internet for more than a few sites of “serious” comics criticism, and even less that offer an alternative narrative less beholden to fandom. The hope that the internet would lead to a surge of self-publishing and hence sites consistently promulgating quality reviews and essays on comics was nothing but a pipedream. If anything, what we have is consolidation and a return to the mean. The Comics Comics project now subsumed to the new TCJ.com. The Panelists dead and now absorbed by the same. Even Sean T. Collins, Jog, Chris Mautner, Ken Parile, and Tucker Stone are now writing a significant proportion of their long form criticism for the site. Robin McConnell of Inkstuds hosts occasional critical discussions with the usual suspects listed above. The writers of The Comics Grid continue their quiet, scholarly course. There are few other umbrella organizations of note in North America as far as serious comics criticism is concerned.

This is certainly no fault of Dan Nadel and Tim Hodler who have crafted a site which has attracted the best talents to its shores. In a field where money is of secondary concern, it is the prestige, professionalism, community, and readership (the numbers and quality) which count the most. Both Nadel and Hodler should be commended for their dedication to preserving the legacy of the print Journal (with all the longstanding deficiences intact I should add).

The one bright spot in this age of digital publication is that The Comics Journal no longer holds a monopoly on the best long form reviews available on any particular comic. This situation is certainly preferable to the one in the late 80s and 90s when The Comics Journal was virtually the only game in town. That position has since been displaced by a host of blogs and newspaper websites. Think of any of the marquee comics of the past year and one will be pleasantly surprised to find that the Journal no longer holds “exclusive rights” to serious and informed discussion of those books.

What is missing however is any concentration of this talent to rival a single website like TCJ.com. Without this, and despite the efforts of a dedicated pool of link bloggers, many of these articles will remain unread and unloved. More significantly, it suggests a level of homogeneity seldom seen in other artforms (at least at this end of the spectrum). That no other site or community of critics has come close to challenging TCJ.com in attracting writers of note is a testament to the lack of depth (in numbers and intellectual concerns), diversity, and vision of purveyors of criticism; a problem exacerbated by a shrinking or stagnant comics readership.