In a short non-fiction essay, “The Spirit of Place,” D.H. Lawrence rejects the idea that young men come to America for freedom. They go west, he argues, simply to “get away from everything they are and have been.” For Lawrence, those who come to America confuse the slavishness of escapism for the authority that comes with actual freedom. “It is not freedom,” he contends, “till you find something you really positively want to be. And people in America have always been shouting about things they are not.” This negative freedom, which is to Lawrence not really freedom at all, but “the sound of chains rattling,” has worked to undermine the true freedom of place, the kind in which a person has responsibilities, “a believing community” organically understood rather than an “idealistic halfness” petulantly professed. “Men are freest when most unconscious of freedom,” he concludes.

Matthew VanDyke is an interesting study in what happens when people no longer go to America but away from it to find this peculiar variety of freedom. Profiled in the recent Marshall Curry documentary Point and Shoot, Baltimore native VanDyke grows up with few friends and little masculine influence. His childhood was defined by video games, old movies about Lawrence of Arabia, and struggles with obsessive-compulsive disorder. As an adult he attended Georgetown University Master’s Program in Middle Eastern studies. After graduation, VanDyke continues to be troubled by the sense that he has not proved his manhood. To find this elusive reality he decides to visit the one place a person an American with an obsessive need to wash his hands would not dare to go: the Middle East. A few weeks later he is in North Africa armed with a camera and motorcycle.

After many misadventures, including a detour with the American Army in Iraq where he poses as a photojournalist, VanDyke eventually finds the fame he seeks in a Libyan prison cell, having been captured by Gadhafi’s forces and then freed by advancing coalition-backed militias. An international darling for a few moments, the dazed VanDyke refuses to go back home. He wants to battle with his friends for the freedom of Libya. Soon enough, he is back in the fighting, though fighting might be too strong a word. Mostly he seems to be hanging about videotaping the chaos, trying to give the solemnity and dignity of a revolution to the seemingly trivial and slap-dash proceedings (which characterizes all warfare and likely all revolutions as well), as well as making heroic efforts to overcome his disgust at the lack of sanitation.

The documentary ends with him not only overcoming his dirty-hands phobia – at least overseas – but also debating whether to shoot, to take another man’s life. He misses but he wants to make clear that he meant to do it. He had the guts, the manliness, and the freedom to kill. No phobia there. Mission accomplished.

Yet for all the exciting adventures VanDyke experiences, it is impossible to get out of one’s head the idea of a reenactment, of middle-aged office workers walking through the woods in Civil War uniforms and young men playing paintball between mounds of dirt. It is all so clumsy, so sad and trivial. He travels to Afghanistan to place an American flag in Bin Laden’s house. He makes the first real friends of his life in combat. Van Dyke’s whole life, his whole idea of freedom, consists in this idea of acting, repeating typically dangerous situations under the gaze of the camera, and while the adventures he finds himself in are ostensibly new, they feel old and worn out. VanDyke very much wants to believe otherwise. He wants to believe his experiences are immediately made hallowed through the ever-present camera, which turns the ephemeral and pointless violence he witnesses, the aimless and meandering journey he travels, into something much more. But it doesn’t quite come off. The camera instead dictates his adventures, hollowing out his experiences, transforming a war and people’s lives into an unfunny Jackass skit.

Garibaldi had politics. Byron had poetry. VanDyke has a camera. Context, ultimately, comes to little compared to the camera angle, the breadth of the shot. Whose freedom VanDyke fights for and against whom is immaterial, for the names and lives of the saved are as interchangeable as those who need to be killed. The war’s entire meaning is bound up in the existence of a picture, a video or a Huffington Post article, artifacts that answer one question and one question alone: was the person there or not? Like much recent war literature and movie fare, the thereness trumps what the author or auteur have to say about having gone. Movies like Lone Survivor and American Sniper have been celebrated not so much for what they have to say about the war, but for what they show about it. Some veteran writers have gone so far as to argue that documentaries best represent these particular wars because we live with ubiquitous lenses. Yet it could also be argued – and Marshall’s documentary seems a good example of this – that war documentaries become ignoble through repetition and overcompensate for lack of imagination with documentation.

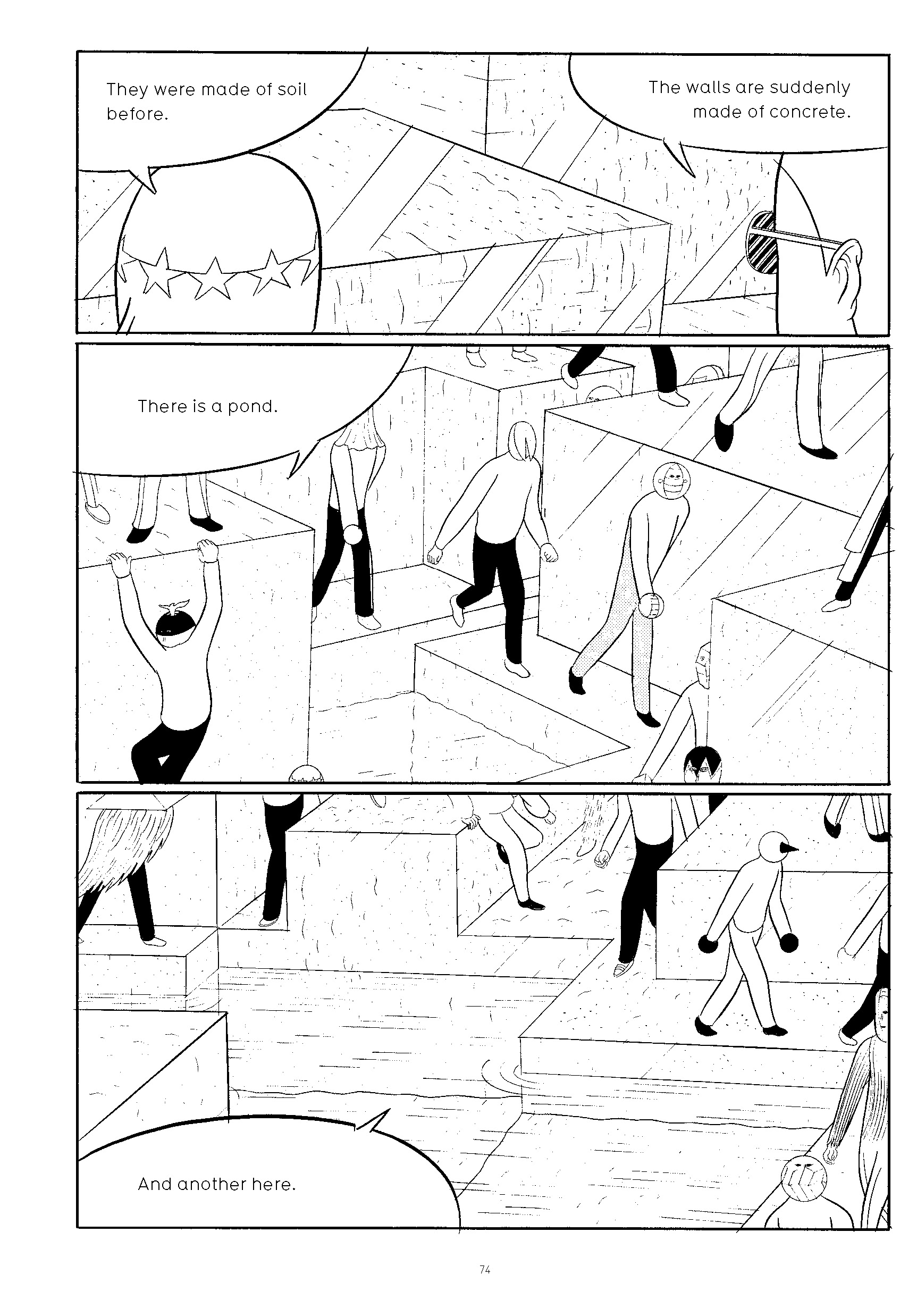

From this perspective, VanDyke’s movement from 27 year-old video-game freedom fighter in his mom’s basement to actual freedom fighter does not seem all that surprising. War is a process of self-creation, and for many lost and insecure boys, a process of self-actualization as well. It has been one for likely much of warfare’s history. Yet in the self-reported story of VanDyke one gets the impression that this process of self-creation is done firmly within the constraints of previous documentaries, movies and stories. With the exception of his time in prison – which Marshall is forced to represent through animation – there is absolutely no space for truly disturbing experiences (i.e., not already expected, not scripted, and not violent) to inform who VanDyke is, or for politics to be anything other than a flimsily applied construct, a set of words used when dialogue is expected.

Watching this young man’s self-portrait, one gets the sense that the war itself, the fight for freedom VanDyke supposedly assists, does exist somewhere. But the particulars of why they fight and what happens after the fight are unimportant. Marshall and VanDyke try to craft the narrative as a triumph over his Western squeamishness. But this is not what happens at all. It is almost as if instead of VanDyke conquering his OCD, his OCD conquers his mind entirely. His adventures give an excuse for the despotic compulsions of his imagination, and validate the incessant and never ending cavalcade of toppled dictators and heroic liberators. He no longer has to deal with the particular, with the complications of not knowing exactly what to do, with a life without routine, without a script. He only has to clean again and again a damned spot that he has made everyone else believe is there, to purify the perception of weakness and captivity that a lifetime of cameras has made a tyrannical obsession. For what better way to pretend at dignity for ourselves, to make music with our chains, then to perpetually reenact the violence that keeps us bound?