In 1947, Life Magazine asked a bunch of famous cartoonists to draw their famous characters blindfolded. The result? Hilarious hi-jinks, of course…and something that looked an awful lot like high art.

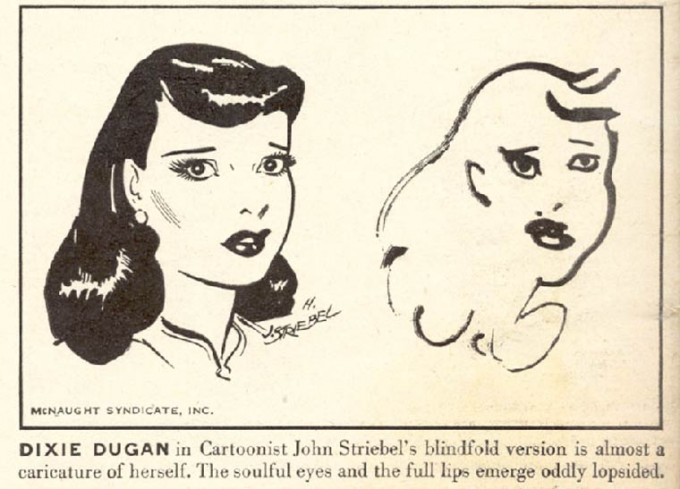

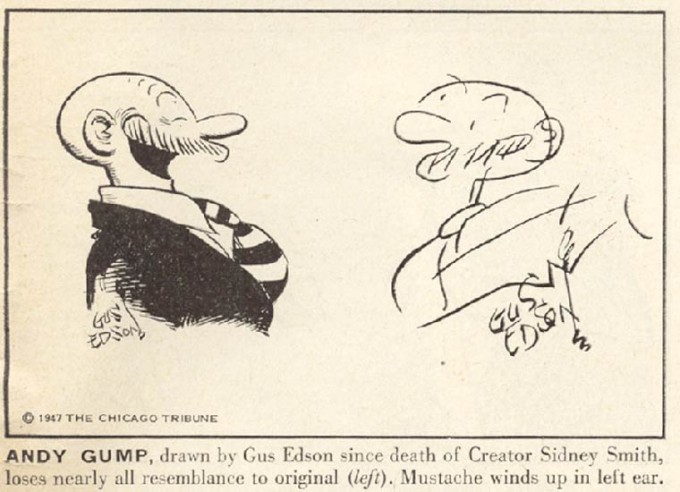

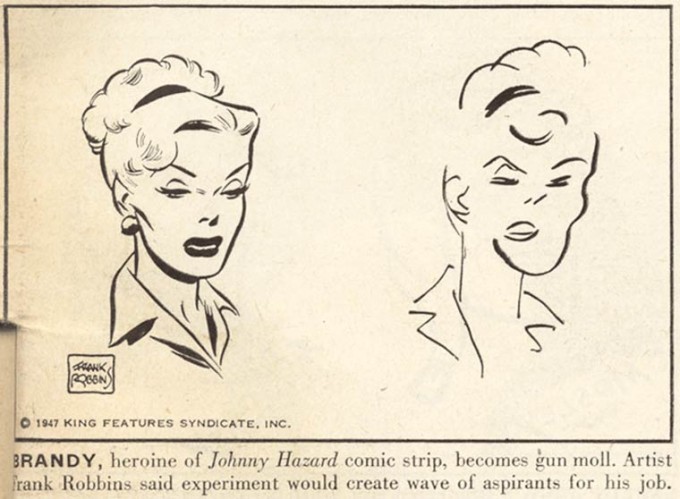

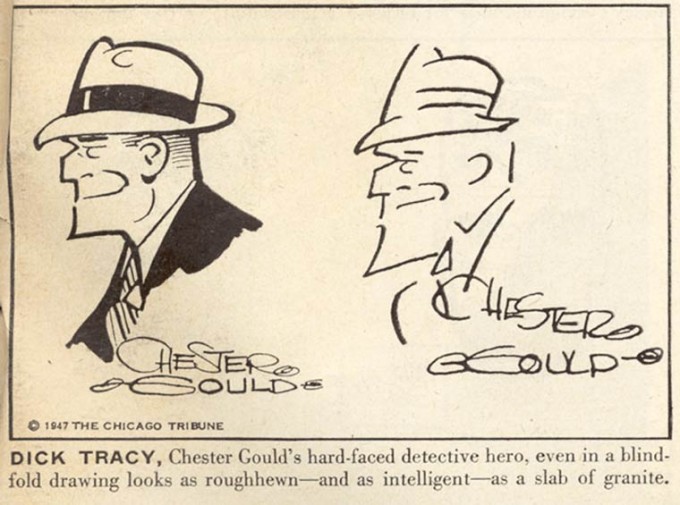

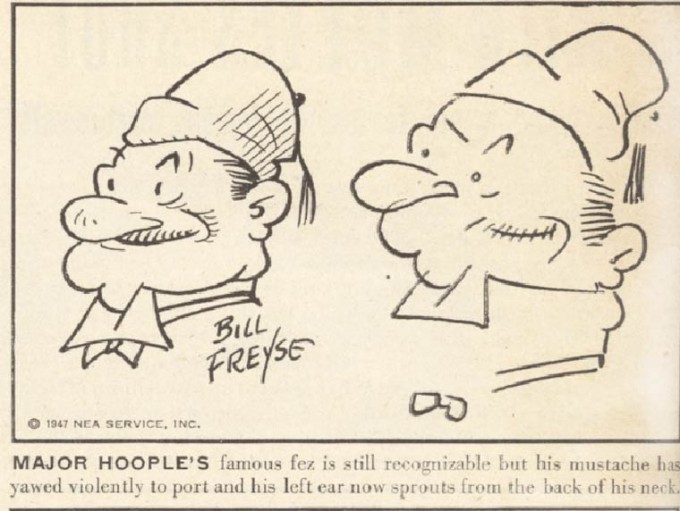

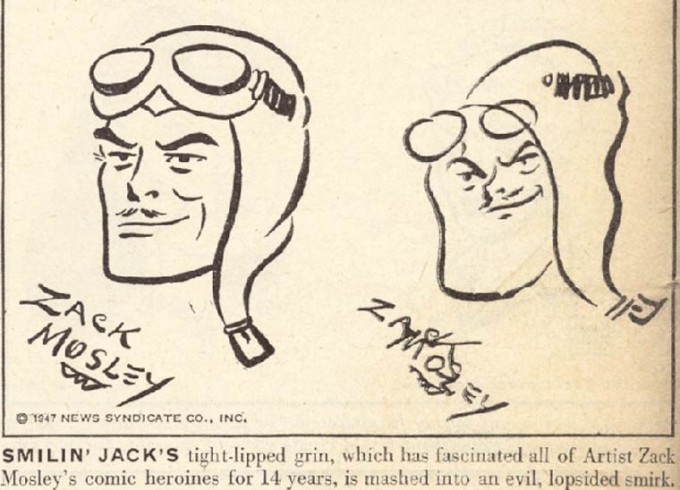

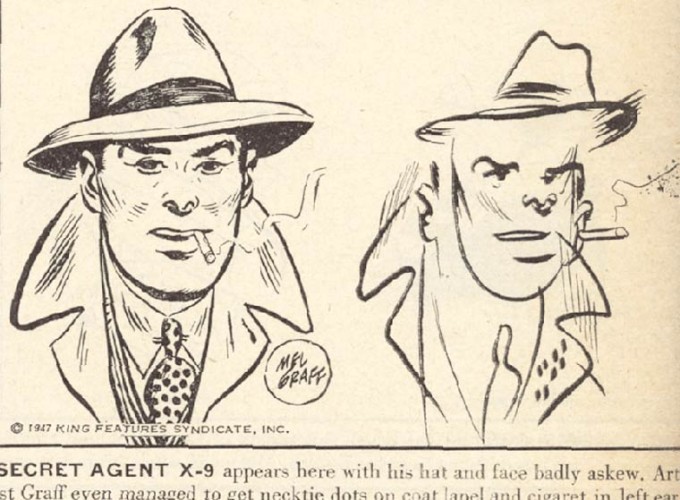

That’s not exactly how Life presented the exercise. The editors instead emphasized the wacky wrongness of the characters; the anatomical, inconsistencies. Dixie Dugan is “almost a caricature of herself”, the eyes and “full lips” appearing “lopsided”. Gus Edson’s Andy Gump “loses nearly all resemblance to the original” and his moustache ends up by his ear. Suddenly, these folks who can draw can’t draw, and that’s funny.

Half a century further down the road of deskilling though, it doesn’t look all that funny. Rather, the drift off-brand is validating. Striebel’s tight, eyes-open illustration of Dixie Dugan looks like bland advertising boilerplate; the blindfolded version, with the loose, gestural strokes and the varied line-weights, has a lot more energy — a highbrow modernist sketch emphasizing individualistic brio rather than a commercial hack job. Similarly, Edson’s perfected Gump looks fusty and antiquated in its slick cartoonishness, while the stick figure outline looks like the work of someone who’s seen Fort Thunder, and knows the joys of messiness.

You could argue that this exercise exposes the shallowness of high art pretensions and the idiocy of contemporary art. “Look, my kid could do that,and with his eyes closed no less!” Or you could say that it reveals the dullness of the cartoonists, whose drab workmanlike images need a shot of modern art practice to give them life.

Less polemically, though you could instead see the exercise as an object lesson (with illustrations) of why deskilling has become so central to contemporary art, and to highbrow/lowbrow distinctions. Comic strips emphasize professional finish, reproducibility, and iconic characters — the point is a recognizable, consistent product, which obscures the contribution of the artist, so that (for example) Gus Edson can replace Sidney Smith, and the Gump remains the same.

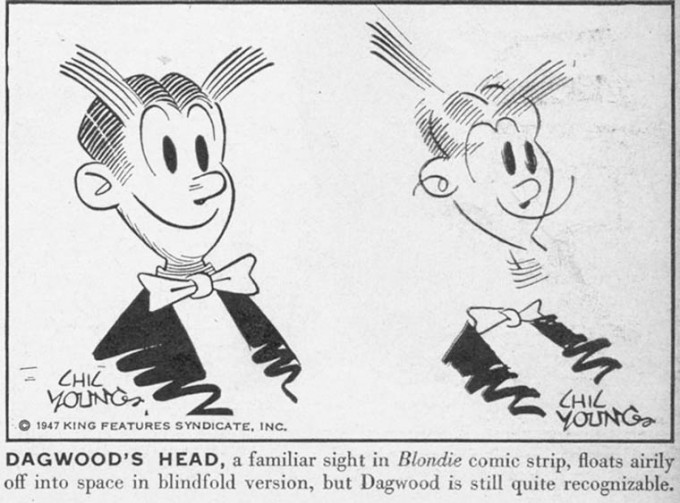

But with eyes closed, the artists are no longer able to be professional. The practiced memes fracture and come apart; literally in the case of Chic Young’s Dagwood, whose head leaves his body. Imperfection equals idiosyncrasy. To draw the same thing over and over perfectly is to be a drone, an assembly line worker. To be an artist, you have to be less sure; the marks have to be placed, not out of habit, but from individual inspiration. Dagwood’s perfect collar disintegrates, and what’s left behind are pen strokes as pen strokes. By closing his eyes, the artist reveals his hand.

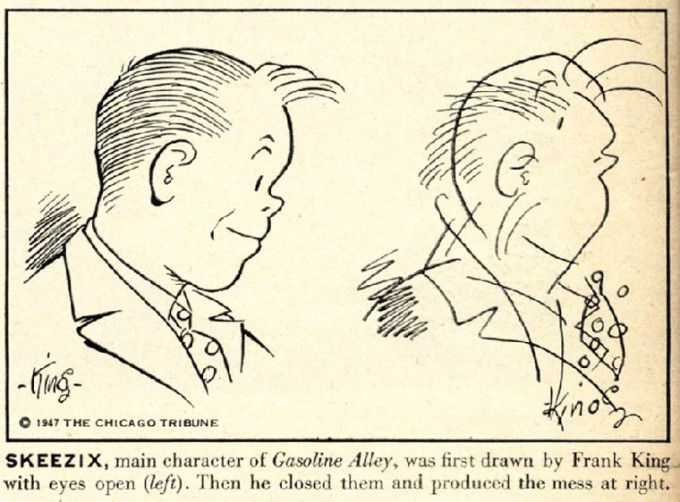

The fact that, in the blink of an eye, Frank King can move from cartoon to cubism is a reminder that the low-art/high-art divide is both more arbitrary, and less wide, than either side likes to admit. Once we recognize that, the juxtaposition can allow us to perceive some of the pleasurable oddness and wrongness in the original drawings — the weird way Dick Tracy’s mouth seems to curve up his cheek and head towards his nose, or those tufts of hair making a bid for freedom on Skeeziks’s brow. And it also lets us think about the cute, iconic professionalism behind modernist semi-abstraction, in which the artist’s tics become their own marketing meme.

Thisexercise also demonstrated, though, how absolute the high art/low art divide can be. Life’s editors were familiar with Picasso I’m sure; Boing Boing’s bloggers (which who reprinted the piece) have seen modern art. Yet the genre assumptions are a barrier, or a blindfold, to seeing what’s happening on the page and/or screen in front of their eyes. For Life (and for the artists themselves), the blindfolded cartoonists are still cartoonists; the drawings with eyes covered are mistakes, or failed attempts, or entertainingly silly errors. Deskilling is seen as a bug, rather than a feature; the drawings are comics that don’t look like comics, rather than something else which looks like itself.

I’ve mentioned before Carl Freedman’s point that genre precedes art — by which he means that preconceptions about genre determine what we see as art, and what we see when we see art. Are those images above bad comics? Or are they succesfully deskilled high art? Part of what’s especially enjoyable about them is that they’re both and neither. If genre determines what we see as art, then art that messes with genre can cross up the way we see — like looking with our eyes uncovered, or with a blindfold on.

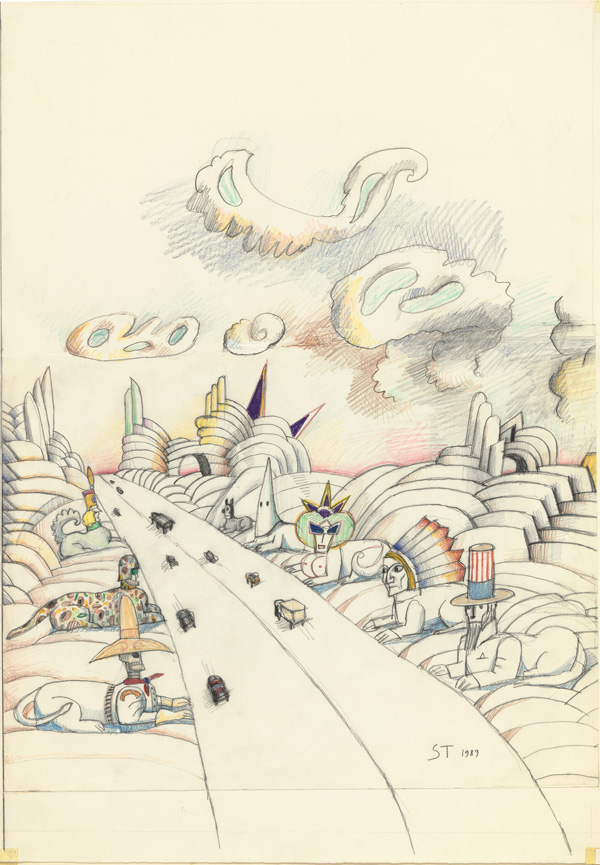

Saul Steinberg, “Las Vegas”