I can restart the Israeli-Palestinian peace process in three words.

But first a lesson in grammar.

Passive voice. Ever heard of it?

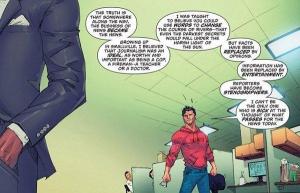

Super-grammarian Geoffrey Pullum has. Daily Planet editor Perry White has too. But White, according to Pullum, has no idea what it is. In J. Michael Straczynski and Shane Davis’ Superman: Earth One, Mr. White explains to cub reporter Clark Kent: “Active sentence structure versus passive structure. A good reporter always goes for the former, never the latter. It’s ‘A dog was killed last night,’ not ‘Last night, a dog was killed.’”

And then Pullum swoops in through a window: “It looks as if the editor of The Daily Planet thinks that it is passive sentence structure to use any adjunct constituent set off by commas. So he would condemn sentences like Michael Corleone’s You’re out, Tom, or Today, I settle all family business, for being passive!”

In his Chronicle of Higher Education article “Passive Writing at the ‘Daily Planet,’” Pullum bemoans the sorry state of grammatical knowledge among not just fictional newspaper editors. Your “freshman-comp TA” and writing gurus Strunk and White get it wrong too. Pullum considers it a serious educational issue.

I teach first-year composition, but my concern isn’t educational. It’s moral.

Passive voice is evil.

If you accept Stan Lee’s superhero prime directive, “With great power comes great responsibility,” then passive voice is a supervillain’s weapon of choice.

Which might explain why politicians use it so often. The Fat Man and Little Boy of literary examples were both launched by the Nixon administration. When press secretary Ron Ziegler was discussing Watergate, and when Secretary of State Henry Kissinger was discussing Vietnam, both deployed the same phrase:

“Mistakes were made.”

Who made the mistakes? Impossible to say. The sentence is missing its subject, the agent, the actor of the action. And there lies the villainy. Passive voice erases responsibility. It’s how bad guys make their escape.

Look at Mysterio. He routinely eludes Spider-Man by dropping smoke bombs and ducking away in the confusion. If you rewrite the sentence

“Mysterio dropped a smoke bomb,”

as

“A smoke bomb was dropped,”

then Mysterio (subject and villain) vanishes twice. He ducks away in the syntactical confusion. Passive voice writes him right out of the sentence.

Perry’s example, “A dog was killed,” actually IS passive voice (whether it happened last night or not), because the sentence masks the identity of the dog-killer. Did Mysterio kill the dog? Did Richard Nixon? Nobody knows.

Which is why reporters like Clark Kent sometimes use passive voice. The police, like the readers of the sentence, are still searching for the killer.

But what if the information is known and the writer obscures it?

That’s where things get ugly.

Reaching past my shelf of comic books, I have The Palestine-Israeli Conflict in hand. Instead of dual-statehood, Dan Cohn-Sherbok and Dawoud El-Alami settle for dual-authorship. And that’s about all they agree on. Each pens his own history. The book is a journey down the same river twice, but in very different boats.

When describing events of 1948, Dawoud El-Alami writes: “Jewish terrorist organizations . . . carried out a massacre of men, women and children in the village of Dier Yassin.” That’s active voice. The subject of the sentence carries out the massacre. In contrast, Dan Cohn-Sherbok describes the same incident with the phrase: “the policy of self-restraint was abandoned.” That’s passive. Who abandoned self-restraint? His syntax doesn’t want to tell.

Cohn-Sherbok goes on to describe a similar incident from 1982: “More than three hundred refuges were massacred.” Passive again. And Dawoud El-Alami, to no surprise, employs active voice again: “The militia massacred between seven hundred and one thousand people (some reports say two thousand).”

Technically, the two pairs of sentences don’t contradict (even mathematically, since two thousand is “more than” three hundred). But Cohn-Sherbok employs passive voice at its immoral worse. His syntax erases responsibility.

Now I’m not suggesting that the “Palestinian Perspective” half of The Palestine-Israeli Conflict is any more accurate than the “Jewish Perspective.” Dawoud El-Alami has his own array of rhetorical maneuvers for ducking blame.

If you’re wondering about my political biases, I find myself agonizingly sympathetic to both sides. The most guilty party is England, who, desperate to fight Nazi Germany, promised the same homeland to two different aspiring nations. The results were horrifically predictable.

But if you don’t think England is responsible, then this is a job for passive voice:

“The Jews and the Palestinians were promised the same land.”

Promised by whom? By Mysterio’s trademark cloud of syntactical smoke.

At least Clark Kent isn’t fooled. He recently escaped the grammatical misinformation of Perry White to strike out on his own as a blogger. It was big news. Last November, after a discussion of the Israel-Hamas cease-fire, NPR’s Talk of the Nation host Neal Conan explained:

After more than 70 years as a mild-mannered reporter, Superman quit his day job at The Daily Planet. A fed-up Clark Kent delivered a diatribe in front of the entire newsroom on his way out the door. ‘I was taught to believe you could use words to change the course of rivers,’ he said, ‘that even the darkest secrets would fall under the harsh light of the sun.’

Are you listening, Dan and Dawoud? Your words are changing the course of rivers. Take responsibility for your subjects, even their darkest secrets.

That’s the first step in this English professor’s plan for world peace:

Ban passive voice.

[And for the super-grammarians out there, I should point out that both “The dog was killed” and “The dog was killed by Richard Nixon” are examples of passive voice, even though the second sentence apprehends the killer. Only the first, the agentless subgroup of passive voice, is evil. The second is just criminally clumsy.]