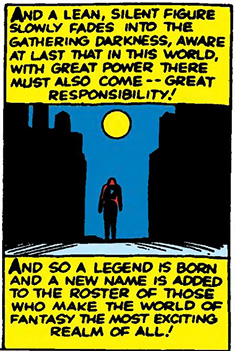

Marvel Comics’ She-Hulk is perhaps the most high-profile of their many female characters that are derivative of successful pre-existing male characters. However, three decades since she first appeared in Savage She-Hulk #1, writers (especially John Byrne) have worked to develop the character into someone who is not merely a shadow of a male character with no defining personality or history of her own in titles like The Avengers, Fantastic Four and eventually her second solo book, The Sensational She-Hulk. In fact, by the time Dan Slott got around to writing her solo title in 2005, the character’s winking reference to her own status as a comic book character became one of her defining features, and Slott developed this into a knowing and charming run, that while not free of problems, represents some of Marvel’s best output in the 21st century.

At the heart of Dan Slott’s run on what are referred to as She-Hulk volumes 1 & 2 (despite being the 3rd and 4th volumes of She-Hulk titles) is an alternately critical and nostalgic concern with the subjects of continuity and rupture in serialized superhero comic book narratives. Slott uses the space of a marginal title that probably never sold very well to undertake a meta-narrative project that is as much enmeshed in the insularity of the mainstream comics world (what many people refer to as “continuity porn”) as it is a critique of such obsessions.

At the heart of Dan Slott’s run on what are referred to as She-Hulk volumes 1 & 2 (despite being the 3rd and 4th volumes of She-Hulk titles) is an alternately critical and nostalgic concern with the subjects of continuity and rupture in serialized superhero comic book narratives. Slott uses the space of a marginal title that probably never sold very well to undertake a meta-narrative project that is as much enmeshed in the insularity of the mainstream comics world (what many people refer to as “continuity porn”) as it is a critique of such obsessions.

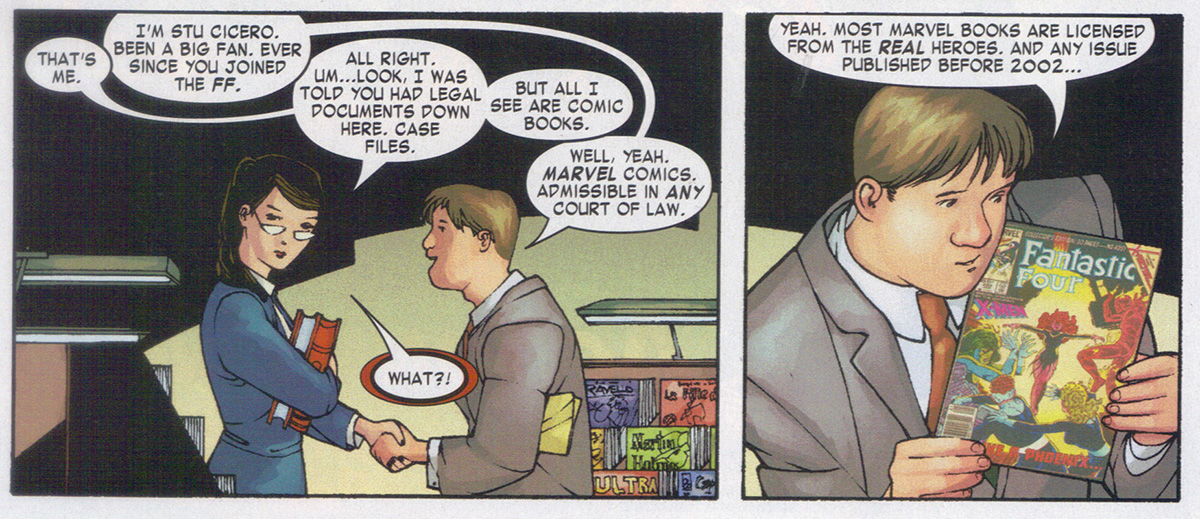

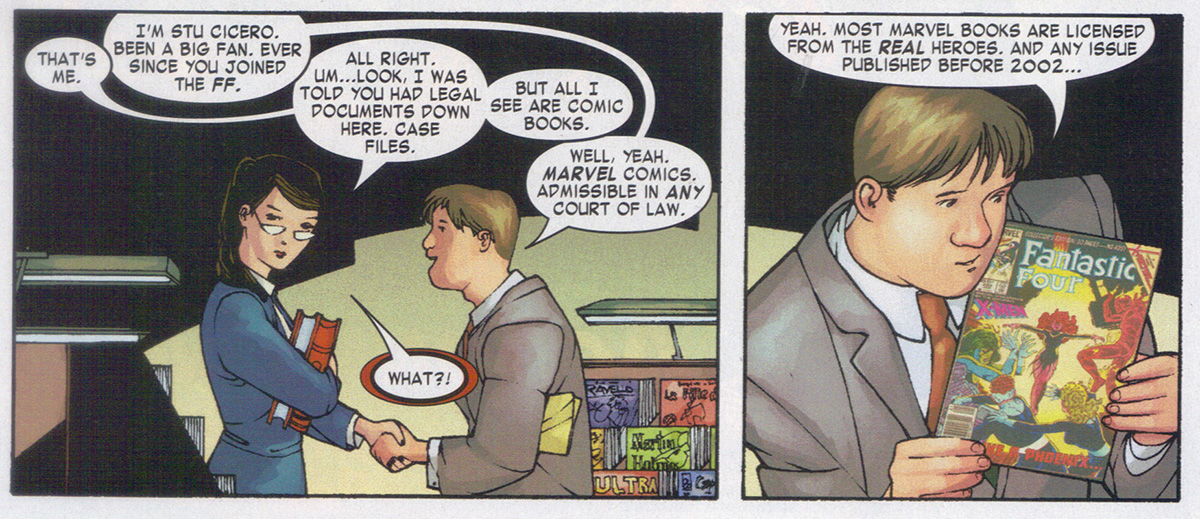

There is a sense of adult whimsy that really helps to keep this run afloat. Some comics critics, like Jeet Heer, may claim that “superheroes for adults is like porn for kids” (in other words, a bad idea) or that it is time to abandon superheroes altogether, but I think Slott’s work here proves that wrong, as it eschews the self-serious attitude of typical post-Watchmen/Dark Knight “adult” superhero comics in favor of embracing the ridiculousness of the genre that is best appreciated by long-time fans who have learned to have a sense of humor about their beloved Marvel comics stories. Aiding She-Hulk in this meta-project is Stu Cicero, who often seems to be a mouthpiece for Slott himself, though that kind of problematic direct voicing of the author’s position on the tradition of superhero comics is often skewered by the series’ afore-mentioned sense of humor.

Stu works in the law library at Goodman, Lieber, Kurtzberg & Holliway, where the majority of the action in Slott’s two She-Hulk runs occurs. Jennifer Walters aka She-Hulk begins working at this firm that specializes in “super-human law” after losing her job as an assistant D.A. (all the times she helped to save the world left all the cases she tried susceptible to appeal as owing her their lives effectively prejudices all juries) and then being kicked out of Avengers’ Mansion for her irresponsible hard-partying ways. Her new boss’s insistence that she work in her civilian guise of Jennifer Walters means her identity as She-Hulk won’t compromise her cases. Furthermore, her connections to the superhero community would be helpful in drawing new clients.

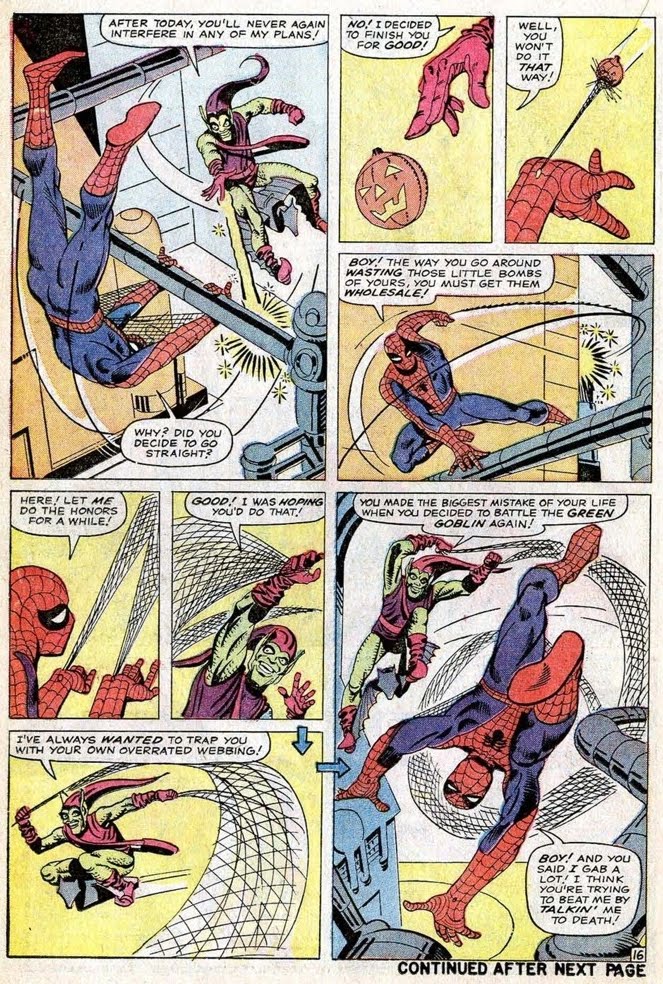

As a law firm that specializes in trying cases involving superhumans, one of its greatest assets is the comic book section of its law library. The conceit in these series is that Marvel Comics exist within the Marvel Universe (something that has been established since the very early days—Johnny Storm is shown reading a Hulk comic back in Fantastic Four #5 and the Marvel Bullpen has been depicted in various titles countless times), telling the “true” stories of the adventures of Marvel superheroes. Stamped by the Comics Code Authority, “a Federal Agency,” they are admissible as evidence in court. Now, this is of course ridiculous. The Comics Code Authority was never a federal agency, but even more absurd is the idea that comic books would ever be taken so seriously. How could anyone expect the stuff depicted in comics between 1961 and 2002 to be internally consistent? How can anyone expect that everything printed in a Marvel Comic, down to the most obscure detail be made to jive with every other thing as to be of value in a trial or lawsuit? But therein lies what makes this run of She-Hulk so great. The comic has a lot of respect and attention to the minute convolutions of Marvel Comic history—one might even go so far to say it has a reverence for them—while never forgetting they are just funny books. The fun is in engaging with the stories to find ways as fans to make sense of it all (or just make fun of the fact that it doesn’t make sense), but not to take it all so seriously that you come off as if trying to argue a federal case from comic books.

It is with this conceit, tongue planted firmly in cheek and the ability to comment on the very kind of comics that She-Hulk is an example of firmly enmeshed into its narratives, that Slott is able to get away with a lot. Foremost, among these things is to examine the role of sex and She-Hulk’s sexuality in her past and the way it has shaped views of her character. This is not free of problems and I am conflicted about how it is depicted, but it does not wholly undermine the project. While I appreciate the frank discussion of She-Hulk’s sexual appetites and the effort later to directly address and rehabilitate the adolescent approach to sex common to this whole genre of comics, there is a bit of slut-shaming going on and more than one gratuitous scene that is in line with the sexualized objectification of the She-Hulk character and her Amazonian voluptuousness. In other words, like many attempts at satire, this comic sometimes crosses the line into being what it seems to want to be commenting on. (But this is not just a problem with mainstream superhero comics—as much as I love Love and Rockets, I sometimes get the same feeling from Gilbert Hernandez’s work). It is for this reason that Juan Bobillo’s pencils seems to serve Slott’s series the best. It has a kind of soft rounded cartoony look that makes She-Hulk look a little chubby and cute in both her incarnations (more Maggie Chascarillo than Penny Century) and that gives the series’ whimsy a visual resonance. The rest of the artists on the series vary in their skill and appropriateness to the material and sometimes fall into the questionable range of Heavy Metal-like cheesecake.

It is with this conceit, tongue planted firmly in cheek and the ability to comment on the very kind of comics that She-Hulk is an example of firmly enmeshed into its narratives, that Slott is able to get away with a lot. Foremost, among these things is to examine the role of sex and She-Hulk’s sexuality in her past and the way it has shaped views of her character. This is not free of problems and I am conflicted about how it is depicted, but it does not wholly undermine the project. While I appreciate the frank discussion of She-Hulk’s sexual appetites and the effort later to directly address and rehabilitate the adolescent approach to sex common to this whole genre of comics, there is a bit of slut-shaming going on and more than one gratuitous scene that is in line with the sexualized objectification of the She-Hulk character and her Amazonian voluptuousness. In other words, like many attempts at satire, this comic sometimes crosses the line into being what it seems to want to be commenting on. (But this is not just a problem with mainstream superhero comics—as much as I love Love and Rockets, I sometimes get the same feeling from Gilbert Hernandez’s work). It is for this reason that Juan Bobillo’s pencils seems to serve Slott’s series the best. It has a kind of soft rounded cartoony look that makes She-Hulk look a little chubby and cute in both her incarnations (more Maggie Chascarillo than Penny Century) and that gives the series’ whimsy a visual resonance. The rest of the artists on the series vary in their skill and appropriateness to the material and sometimes fall into the questionable range of Heavy Metal-like cheesecake.

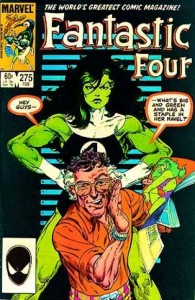

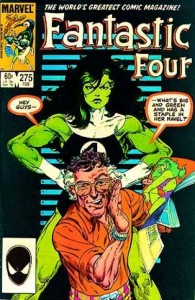

The meta-fictional aspect of this She-Hulk run is one that has its origins in the first printing of her story, as the only reason she even exists is that Stan Lee, worried that CBS would use the success of The Incredible Hulk TV show to create a female version of the character, rushed one to print first in order to claim the trademark on her. From her first appearance, she served a meta-purpose—not the purpose of a story that needed telling or that was even necessarily worth telling, but the purpose of protecting control of a brand. That first series—Savage She-Hulk (1980-82)—demonstrates that in its weakness. The Sensational She-Hulk, (1989-94) written and drawn in part by John Byrne is by most accounts a lot better. I have only ever read a handful of its issues (they are on what I call my “all-time pull list”), but one of the things that is notable about the series is She-Hulk’s tendency to directly address the reader, breaking the fourth wall, so to speak. She often acts as if she knows she is in a comic—but even more often than that she is frequently depicted in various forms of wardrobe distress. There is also a whole issue of Fantastic Four (#275—also written by Byrne) that centers around her efforts to stop a tabloid publisher (depicted, not coincidentally, to look like Stan Lee) from going to print with nude photos of the emerald giantess, taken from helicopter as she sunbathed on the roof of the Baxter Building.

The meta-fictional aspect of this She-Hulk run is one that has its origins in the first printing of her story, as the only reason she even exists is that Stan Lee, worried that CBS would use the success of The Incredible Hulk TV show to create a female version of the character, rushed one to print first in order to claim the trademark on her. From her first appearance, she served a meta-purpose—not the purpose of a story that needed telling or that was even necessarily worth telling, but the purpose of protecting control of a brand. That first series—Savage She-Hulk (1980-82)—demonstrates that in its weakness. The Sensational She-Hulk, (1989-94) written and drawn in part by John Byrne is by most accounts a lot better. I have only ever read a handful of its issues (they are on what I call my “all-time pull list”), but one of the things that is notable about the series is She-Hulk’s tendency to directly address the reader, breaking the fourth wall, so to speak. She often acts as if she knows she is in a comic—but even more often than that she is frequently depicted in various forms of wardrobe distress. There is also a whole issue of Fantastic Four (#275—also written by Byrne) that centers around her efforts to stop a tabloid publisher (depicted, not coincidentally, to look like Stan Lee) from going to print with nude photos of the emerald giantess, taken from helicopter as she sunbathed on the roof of the Baxter Building.

While not part of her original conception, unlike her cousin Bruce Banner/The Hulk, Jennifer Walters/She-Hulk’s transformation seems to have a lot more to do with uninhibited sexuality and sexual appetite than with anger. Sure, She-Hulk gets mad and smashes stuff, but since for the most part she can control her transformation and even prefers her She-Hulk identity and remains in it most of the time (for months or years at a time), anger has less to do with it than her desire. Slott’s run on the title explores a key part of that desire—Jennifer Walters’s desire to escape her petite less assertive human form. Jennifer Walters has the typical social inhibitions, especially ones that are used to deny ourselves pleasure and immediate gratification (for good or ill), while for the most part, She-Hulk has no such compunctions.

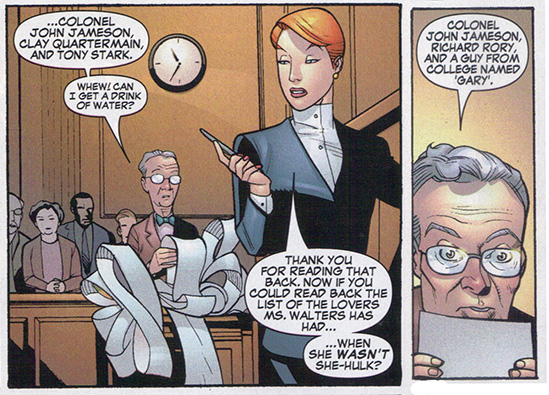

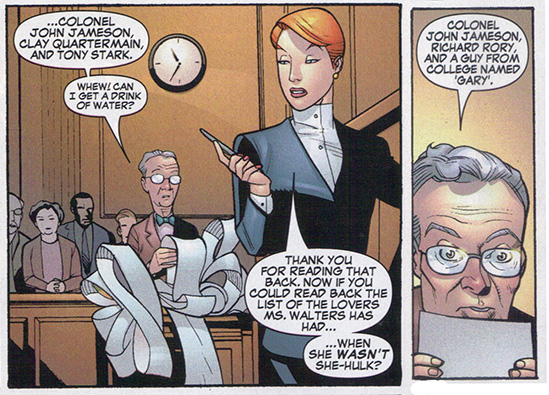

As such, the fact that She-Hulk engages in lots of casual sex becomes a defining part of her character and a conflict within the comic (her bringing home a string of men without proper security clearance to the Avenger Mansion for one-night stands is part of what gets her kicked out). It is a problematic, but fascinating aspect—on the one hand, explicitly addressing sex and sexuality is something Marvel comics hardly ever do in a way that could be considered mature (and by mature, I don’t mean humorless—sex can and often is funny, absurd, irrational), but as I mentioned before it also falls into the trap letting sexuality overly define her character. At one point, she forced under oath to list all the people she’s slept with as She-Hulk (too many to actually list in the comic, instead the panels transition to the court reporter reading back a scrolling list) as opposed to how many she has slept with in her normal human identity (around three). It is this kind of stuff that undermines Slott’s work to establish her character as a formidable lawyer—not because we don’t see her solving cases and doing research, all the things trial lawyers do, but because her sexualization is always at the forefront no matter what else she is doing.

Yet, despite this short-coming, Slott’s She-Hulk series tells some interesting stories and uses its self-awareness to explore some of the very troubling notions of sex and sexuality in Marvel comics that plague the title. Foremost among these is a story revolving around a sexual assault case against the former Avenger, Starfox (not to be confused with the anthropomorphic fox video game character).

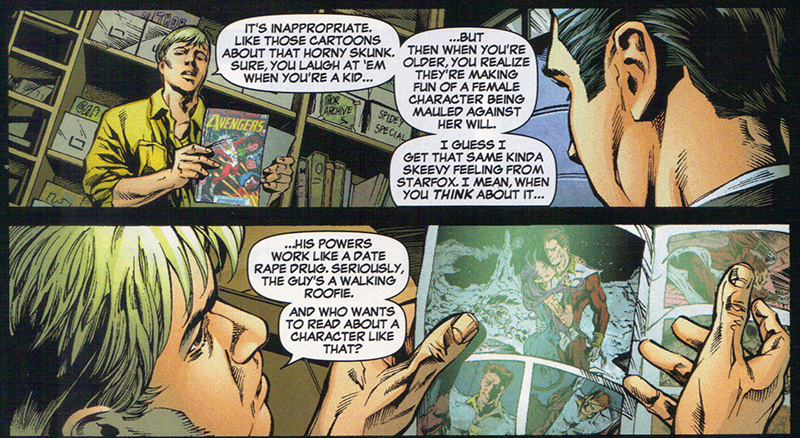

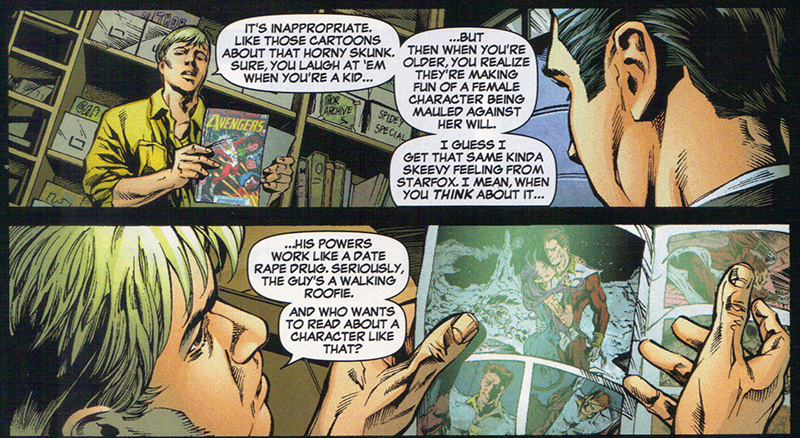

Even though Starfox was first introduced in the 1970s, he is definitely a character often associated with the 1980s. In addition to his super strength and vitality and his ability to fly, his main power makes him, in the words of Stu Cicero, “a walking roofie.” He has the power to calm people down, make them open to suggestion, “stimulate their pleasure centers” (whatever that means) and make them infatuated with him. Starfox is a character, at least in his hey-day as an Avenger, who was often played for a laugh. He was a libidinous lothario that the ladies drooled over and/or who constantly pursued them. However, the nature of his power puts his appeal into a questionable zone. What does it mean when your power influences people to want to sleep with you? How is that really different from a roofie or being a mind control rapist like the Purple Man? As a kid I never thought about it, but the adults who were writing the Avengers back in the mid-80s should have known better.

Slott clearly does know better and uses the plot arc of Starfox being accused of abusing his power to put this explanation into the mouth of Stu Cicero. Stu uses an example even folks not familiar with superhero comics should be able to understand: Pepe LePew—the horny skunk who is the Warner Bros. cartoon poster child for normalizing sexual assault through comedy.

Starfox’s dismissive attitudes to the allegation and his apparent lack of regret serves as a kind of stand-in for the stereotypical superhero comics reader, biding his time through “the boring parts” (women complaining about harassment and assault) and awaiting his eventual exoneration and/or escape to go on more salacious intergalactic adventures. The victim’s testimony, however, leads to She-Hulk realizing that her own past tryst with Starfox may have been influenced by his power. She tracks him down, and he gets his “exciting part”—a fight with She-Hulk wherein she kicks him in the nuts, but he is transported off-planet and out of reach by his influential and cosmically powered father (Mentor of the Titan Eternals – more ridiculous obscure continuity stuff). It seems that even in the comic book world the powerful and well-connected can escape the consequences of their actions. But beyond that, the story works to underscore how superhero comics have a history of not following up with the actual consequences of the puerile sexual behaviors and attitudes that have long permeated the genre. Later, it turns out that Starfox’s abuse of his power is a side effect of one of his evil brother Thanos’s schemes. In that way, he is left off the hook for the ultimate consequences of his sexual violence. He is allowed to remain “a hero” to be used by some future writer. However, at the same time as a result of seeing the possible abuse of his powers first hand, he has Moondragon (a character with her own history of abusing her powers for sexual dominance) use her psychic powers to turn them off, so he could never do it again intentionally or inadvertently.

For some people, that last bit of retconning is what is wrong with superhero comes, but I love that kind of stuff. There is a certain pleasure in reading a story that allows the actions of the past to stand, but recasts them in a way that takes into account a broader consciousness of the societal meaning of those actions. In this way, those old Avengers issues with a skeevy Starfox still exist, but now we know that skeeviness was not “heroic.” It allows the reader to correct his or her interpretation of the past, not by convincing us that how he acted in the past was acceptable (or just part of the time in which it was produced and thus excusable), but by reinforcing that it wasn’t. Sure, ideally I may have liked Starfox to have turned out to be the kind of douchebag that he seems to be without any caveats (I never liked the character), but at least now some writer who insists on using him has an excuse for his powers not working the same way anymore.

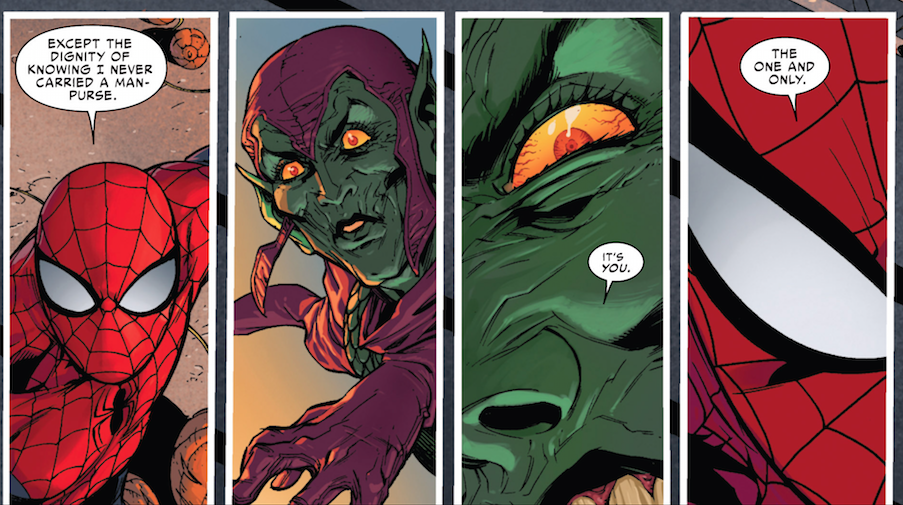

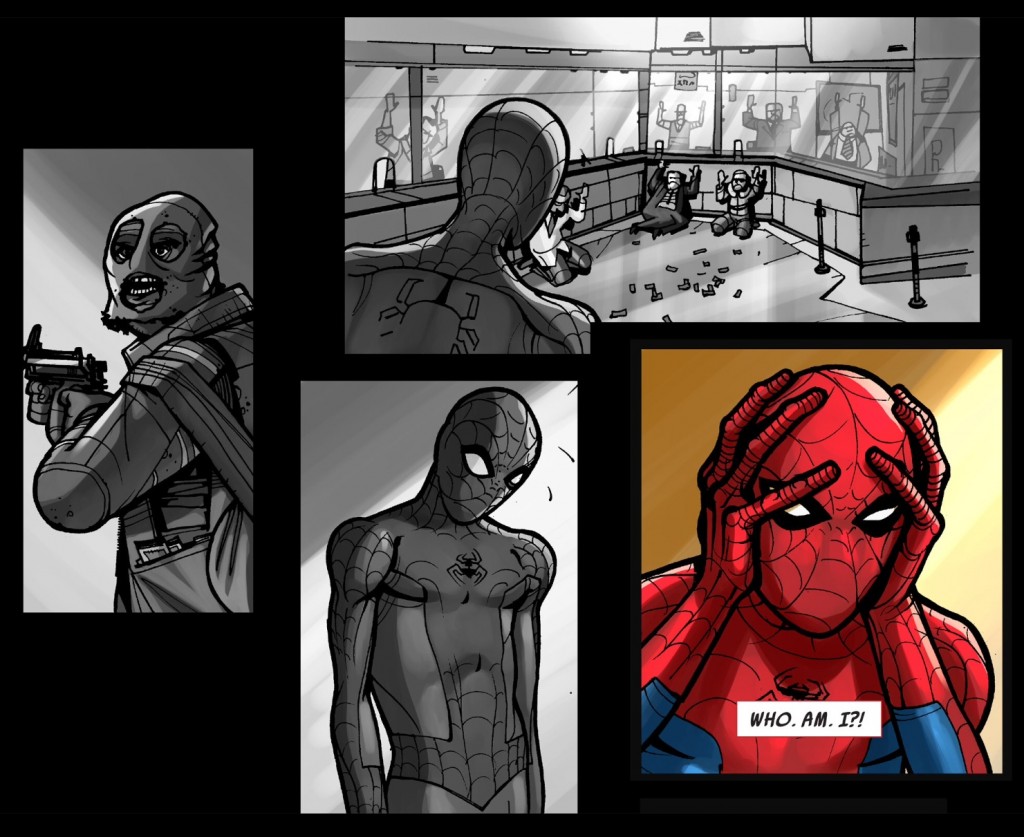

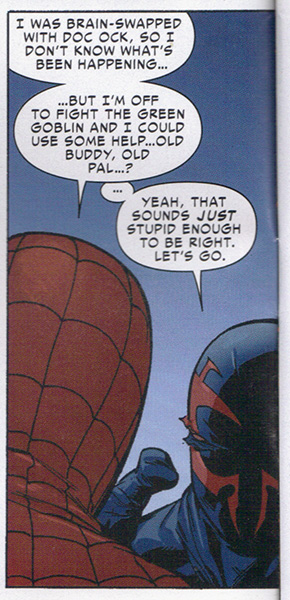

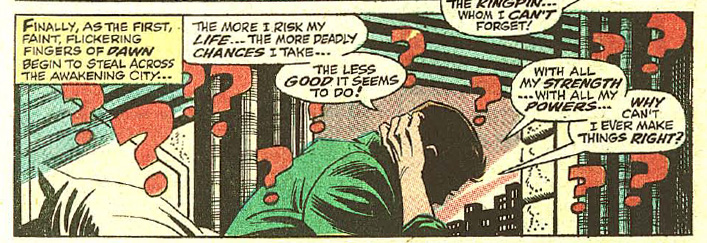

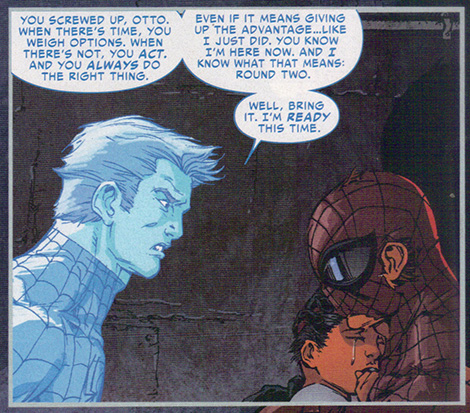

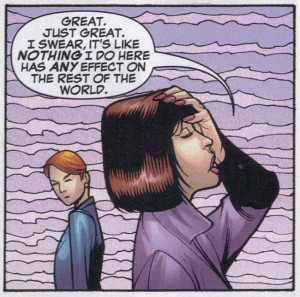

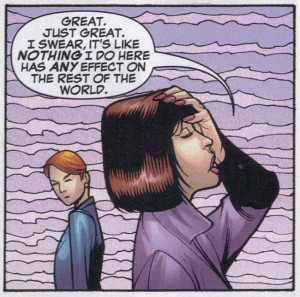

Of course, serialized superhero comics being what they are Starfox’s history remains in an ambiguous space. Everything that happens in these She-Hulk issues could be ignored by a future writer, and Slott seems to have written the series with the knowledge that he was toiling in a sort of bubble within the Marvel Universe. He puts words to that effect into Jennifer Walters’s mouth (and there is a new She-Hulk series starting in February, so we’ll see if that’s the case). But this willingness to grapple with comic book continuity (and an apparently frightening knowledge of it and its inconsistencies) is part of what makes the comic so compelling. Yes, on one level it appears to be more of the insular continuity obsessed dreck that weights down too many titles and definitely Marvel’s big “event” series, but rather than take it seriously, Slott brings the discrepancies and ethical slips to the fore as a way to invigorate his stories with pleasing ambiguity. The inclusion of material comics within the comic narratives lets those ambiguities exist as the seeds of possibility rather than mistakes to be fixed. Peter Parker profiting from his constant defrauding of Daily Bugle publisher, J. Jonah Jameson, the fact that half the beings in the universe were killed by Thanos (and later brought back), the existence of Duckworld, cosmic beings like the Living Tribunal, the contradictory fates of the Leader, and following up with undeveloped characters and stories that have their origins in crap like Jim Shooter’s Secret Wars—all of these things are explored in Slott’s She-Hulk series not with the pedantic obsession of the stereotypical comic nerd, but with good-natured humor and critical nostalgia.

Of course, serialized superhero comics being what they are Starfox’s history remains in an ambiguous space. Everything that happens in these She-Hulk issues could be ignored by a future writer, and Slott seems to have written the series with the knowledge that he was toiling in a sort of bubble within the Marvel Universe. He puts words to that effect into Jennifer Walters’s mouth (and there is a new She-Hulk series starting in February, so we’ll see if that’s the case). But this willingness to grapple with comic book continuity (and an apparently frightening knowledge of it and its inconsistencies) is part of what makes the comic so compelling. Yes, on one level it appears to be more of the insular continuity obsessed dreck that weights down too many titles and definitely Marvel’s big “event” series, but rather than take it seriously, Slott brings the discrepancies and ethical slips to the fore as a way to invigorate his stories with pleasing ambiguity. The inclusion of material comics within the comic narratives lets those ambiguities exist as the seeds of possibility rather than mistakes to be fixed. Peter Parker profiting from his constant defrauding of Daily Bugle publisher, J. Jonah Jameson, the fact that half the beings in the universe were killed by Thanos (and later brought back), the existence of Duckworld, cosmic beings like the Living Tribunal, the contradictory fates of the Leader, and following up with undeveloped characters and stories that have their origins in crap like Jim Shooter’s Secret Wars—all of these things are explored in Slott’s She-Hulk series not with the pedantic obsession of the stereotypical comic nerd, but with good-natured humor and critical nostalgia.

Another aspect of the series that works in its favor (and that has often worked in the favor of some of the best superhero titles) is its strong supporting cast—fellow lawyers Augustus “Pug” Pugliese and Mallory Book, “Awesome Andy” (formerly the Mad Thinker’s Awesome Android) as a general office worker, Two-Gun Kid (the time-displaced former Avenger cowboy) as a form of bounty-hunter/bailiff, Ditto the shape-shifting gopher, comic book-obsessed law library interns, and Southpaw, the angsty teenaged super-villain granddaughter of one of the firm’s partners all serve as interesting companions and foils to She-Hulk. In addition there is a whole range of guest appearances ranging from Hercules to Damage Control to The Leader to a then dead (and later returned) Hawkeye. She-Hulk seeks to embrace, rather than obfuscate, the over-the-top and often incoherent mess of the Marvel Universe.

It is impossible to put myself in a position of someone unfamiliar with the history of the Marvel Universe to know if She-Hulk is the kind of series you can enjoy without that deep knowledge, but I think you can even if you have just some knowledge—even just a passing familiarity with the tropes of the superhero genre would be sufficient (as it is sufficient for an appreciation of something like Alan Moore’s Top Ten). Like any other valuable work, from Shakespeare’s to Junot Diaz’s, knowledge of its many allusions and references improves and deepens comprehension, but is not wholly necessary. Ultimately, the crazy details, characters and events of past stories that Slott dredges up are so absurd and contradictory that for all we know as readers they could be made up on the spot.

Whatever the case, Dan Slott’s She-Hulk is the kind of series that is probably best for long-time fans of Marvel Comics, who still look back fondly on its stories and characters, but have grown up enough to admit their absurdity and their reflection of problematic attitudes. Yes, She-Hulk exists within the skein of the Marvel Universe, and thus may be an example of what Lauren Berlant would call “cruel optimism.” This is when ”the object/scene of desire is itself an obstacle to fulfilling the very wants that bring people to it”—the “scene of desire” in this case being an entertaining and adult superhero comic book immersed in its convoluted continuity—as what there is to work with often recapitulates the very problems the reworking is trying to overcome. And yes, there is not much creators can do within that skein to make lasting change to an editorial approach and historical context that reinforces the social attitudes that makes She-Hulk “a skank” while Tony Stark is a “playboy.” But Slott’s work does work to question those attitudes in an explicit and entertaining way, even if when it comes time to answer them (like in the panels above) suddenly Zzzax strikes again.