The index to the Indie Comics vs. Context roundtable is here.

____________

Dan Walsh’s Garfield Minus Garfield is a site dedicated to creating Beckett-esque (or Schulz-esque) soliloquies by, yes, removing Garfield and his dialogue from Garfield strips.

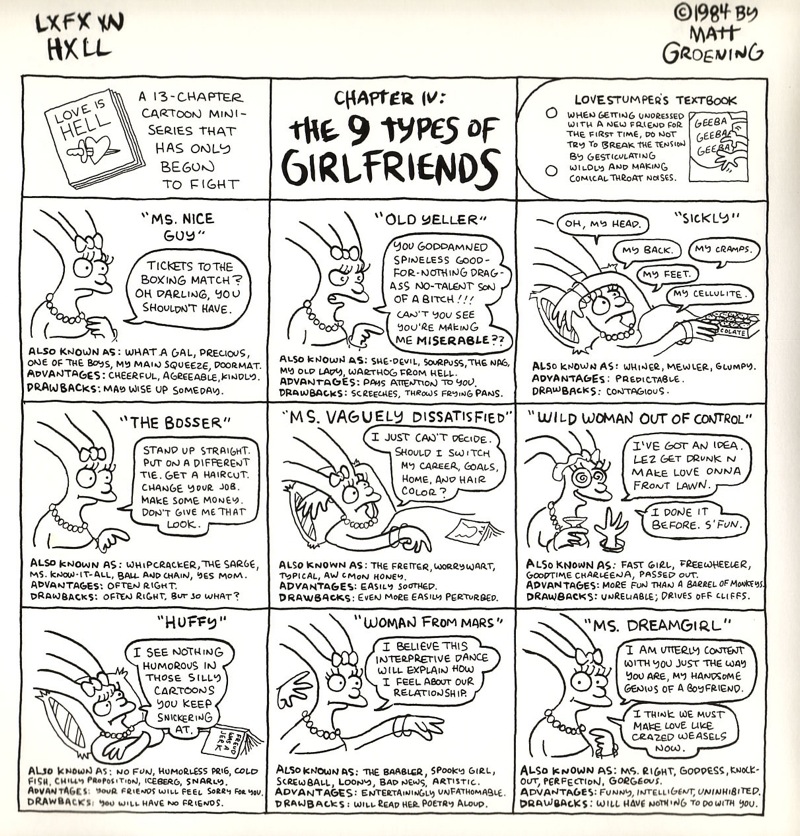

As great as this site is, its lack of originality comes not only from being based on appropriation, but also from a history of Garfield appropriation that I associate with Ben Jones et al. in the Paper Rad collaborative (anyone remember the old castlezzt.net?). I find it an instructive counterpoint to the incredible gulf of quality that exists between Matt Groening’s breathtakingly lame Life in Hell comics, and the towering cultural treasure that The Simpsons has become. Hiring writers is pretty important, obviously, since Groenig’s treacly, patronizing attempts at whimsical spontaneity has taken years to be diluted to a sufficiently non-toxic level. But there’s more to it than that.

While it cashed in on the reliable appeal of self-pitying misogyny, the best part of Life in Hell was always visual, a frequently grid-based evocation of Winsor McCay, but, like Peanuts or Garfield, stripped of all miniscule Art Nouveau detail in order to preserve its readability when reduced to fill available space in the alternative weeklies that ran it, starting in the 1980s and ending last year. It would be hard to argue that it wasn’t at least a somewhat original strip— there were no wisecracking animals, nor clown-guided magical dream zeppelins, nor angst-filled six-year-olds, but, rather, angst-filled rabbits and fez-topped gay midgets, with non-punchlines designed to appeal more to New Yorker subscribers than the Sunday funnies crowd. Along with Jim Davis and Charles Schulz, contemporary work by Keith Haring and Gary Panter could certainly have been an influence, but Groening’s distinctive compositions and renderings made him instantly brand-able as a middlebrow cartoonist.

The non-punchline format is the same thing that makes Garfield Minus Garfield a success. That was not Groening’s problem. I think probably his problem was that he was an artist and not a writer. Some people are multi-talented, but the stigma of collaboration in “fine art” after the rise of the auteur, ironically a byproduct of professional-industrial schemes of specialization, has made for no end of unsatisfying products from those who fall short of being polymath dilettante geniuses (cough, George Lucas, cough). But of course the reason “art by committee” has such a strong negative connotation is owing to the lack of freedom imposed in professional-industrial institutions of modern culture, be they commercial or educational.

Conversely, the victory of the professional-industrial auteur is her autonomy. This autonomy managed somehow to carry over into the collaborative production ethos of The Simpsons, and Matt Groening, either directly or indirectly, is probably very much to be given credit for that. When Lisa was inspired by an ultra-authentic old black sax player (“Bleeding Gums” Murphy) and Dustin Hoffman as an enlightened substitute teacher in the first and second seasons respectively, Groening’s saccharine-sticky fingerprints were all over it.

But in season thirteen, Lisa, portraying Joan of Arc, gets burned at the stake after a trial in which God Himself folds under cross-examination. In season sixteen, Lisa wins an “American Idol”-style singing championship; Homer becomes Lisa’s tour manager, and they have the following exchange.

Homer (angrily): Oh, you LOVE sausage, but you HATE to see it

getting made!

Lisa: I don’t love sausage!

Homer (meekly): Then would you like to see it getting made?

Lisa: NO!

At this point, Matt Groening’s leaden wit was nowhere in sight (not the case, unfortunately, with Futurama). Like any master artist of old (and a few superstar artists today), the apprentices do all the real work. In olden times, though, there was much less of a middlebrow (or perhaps protruding upper lip) to speak of, and so Matt Groening should perhaps be worthy of gratitude for having the relative originality to write himself out of the picture.