This is something of a follow up to my review of Dan Clowes show at the MCA which ran in the Chicago Reader last week.

_______________________

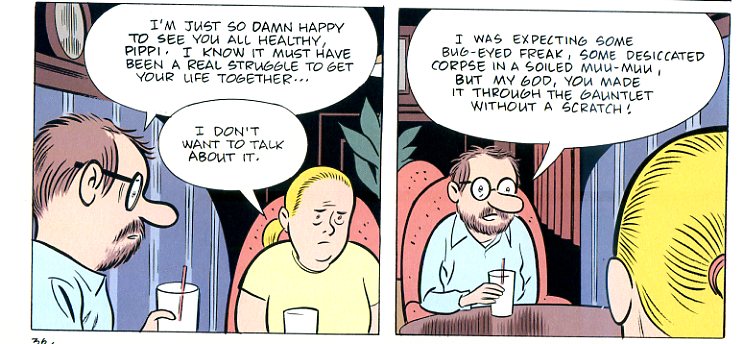

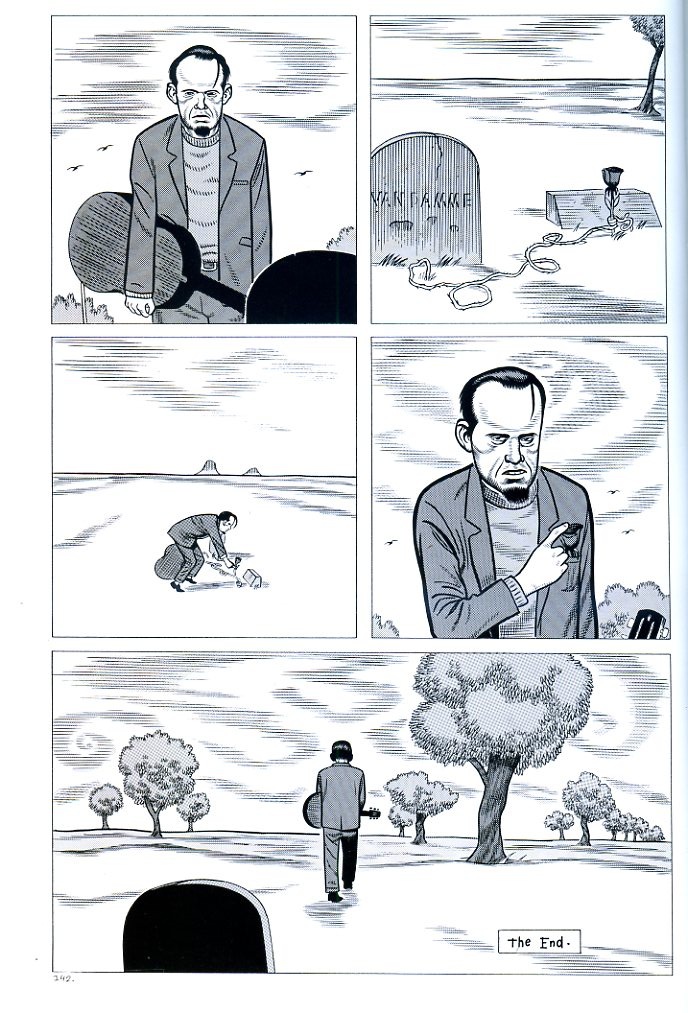

Dan Clowes published Like a Velvet Glove Cast in Iron as a collection in 1993; he published Wilson in 2010. The first is a surreal, dream-like pulp grotesque; the second is an exercise in the quotidian mundanity of literary fiction. Yet, despite their separation in time and genre, the two books have a major plot strand in common. That plot strand consists of two parts. (1) A man searches for his wife who has sunk into sexual debasement. (2) She dies.

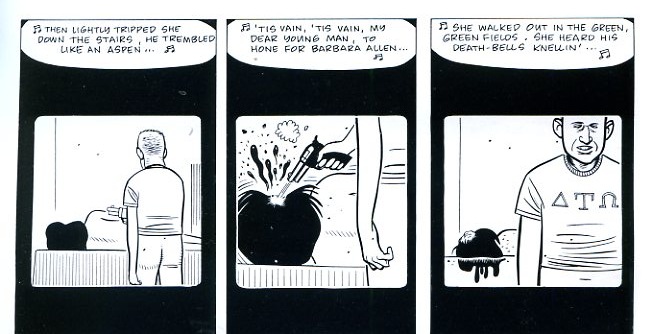

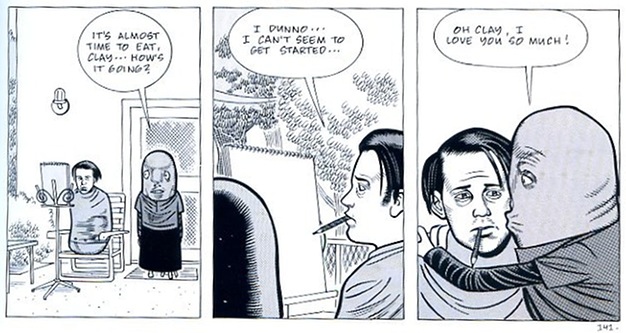

In both comics, also, the women’s stories are simultaneously the center of the narrative and marginal to the psychodrama of the husbands. In Velvet Glove, Barbara Allen’s death happens in a blink-and-you’ll miss it off there on the panel edge joke, and is “retold” through a filmed showing for Clay Loudermilk’s benefit.

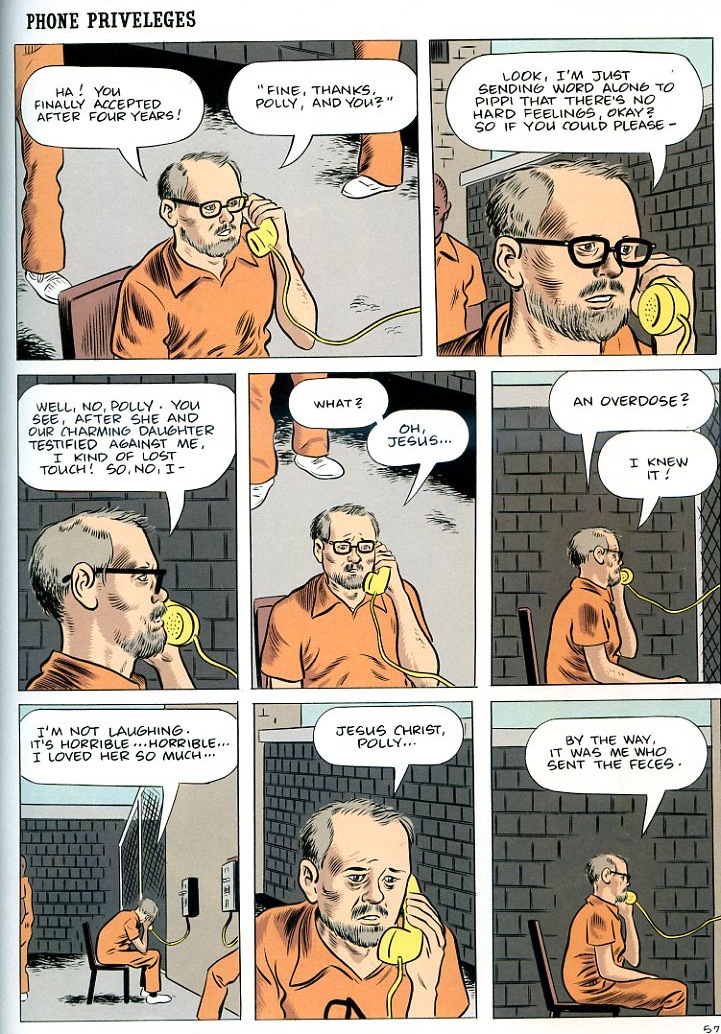

In Wilson, Pippi’s death occurs completely off-panel, narrated to Wilson over the phone as he sits in prison. Both deaths are carefully, deliberately degrading. Barbara is shot in the head during a pornographic fetish film; Pippi dies of a drug overdose. The anti-climactic awfulness of their passings is both a joke and a validation, underlining the nonsensical, adult viciousness of Velvet Glove and the banal, adult viciousness of Wilson. As in a gangsta rap song, or in one of the country death songs that both the names “Barbara Allen” and “Loudermilk” reference, coolness and a kind of manliness or maturity is conveyed through the killing of women, and, through the studied casualness of that killing.

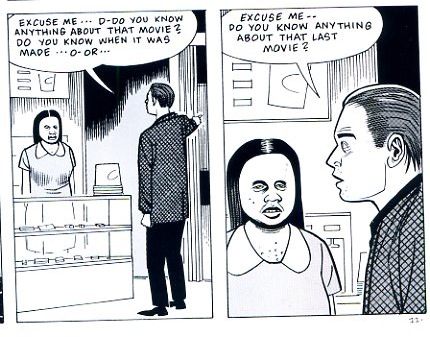

That maturity is in fact what is at issue is made quite clear in both books, albeit in different ways. In Velvet Glove, the search for Barbara Allen is tied repeatedly to the obsessive search for pop culture collectibles…and thereby to the comics medium. Clay Loudermilk discovers Barbara in the opening pages of the comic performing in a violent, bizarre cult fetish film — a provocative, unique bit of alternaculture which stands in for and references Like a Velvet Glove itself. Loudermilk’s shocked need-to-know following the exhibit is diegetically because his wife was in the film, but for alternative comics fans it also has to reference the awakened passion of the collector.

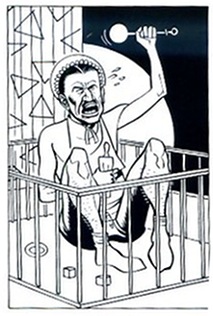

This is only underlined when the search for Barbara becomes obscurely enmeshed with an iconic cartoon character, Mr. Jones, who appeared in old-time advertisements and is improbably tattooed on Clay’s foot — as if his search for obscurities has become a mark of personal identification, so that he has become his own infantile obsessions. When he shakes Mr. Jones, it is not to transcend him, but to embody him. His arms and legs (and Mr. Jones tattoo) are torn off by a steroidal, adolescent-power-fantasy of an antagonist, and Clay becomes a swaddled stump, cared for and fussed over like a baby.

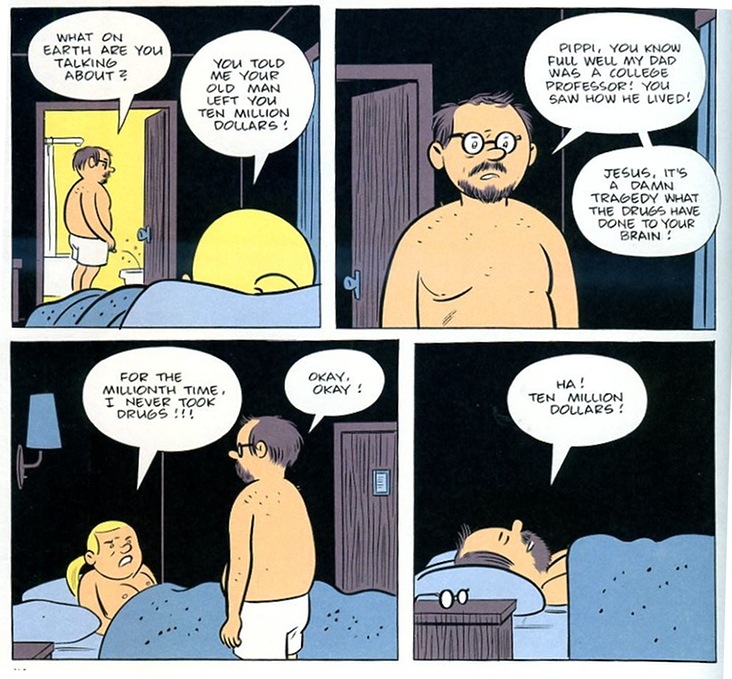

In Wilson, the connection between women, comics, and childhood is routed (as is just about everything in Wilson) through Charles Schulz’ Peanuts. The non-funny gag strips substitute glib profanity and gallow’s humor for Schulz’s bizarre aphasiac non-sequitors and odd tangents, but the model is still clear enough. Pippi, then, is a grown up little red-haired girl; Wilson a grown-up Charlie Brown who, of course, hasn’t really grown up. The shifting styles veer back and forth between cartoonish/neotenous and more realistic, so that Wilson exists in a constantly vacillating iconic no-man’s land between kids’ fodder and serious fiction.

In both works, then, comics, cartooning, childishness, and women function as a knot of meaning, loathing, and desire. Clowes is a very self-aware cartoonist; I don’t think it’s an accident that the initial fetish film Loudermilk sees includes an image of a grown man dressed as a baby and crying.

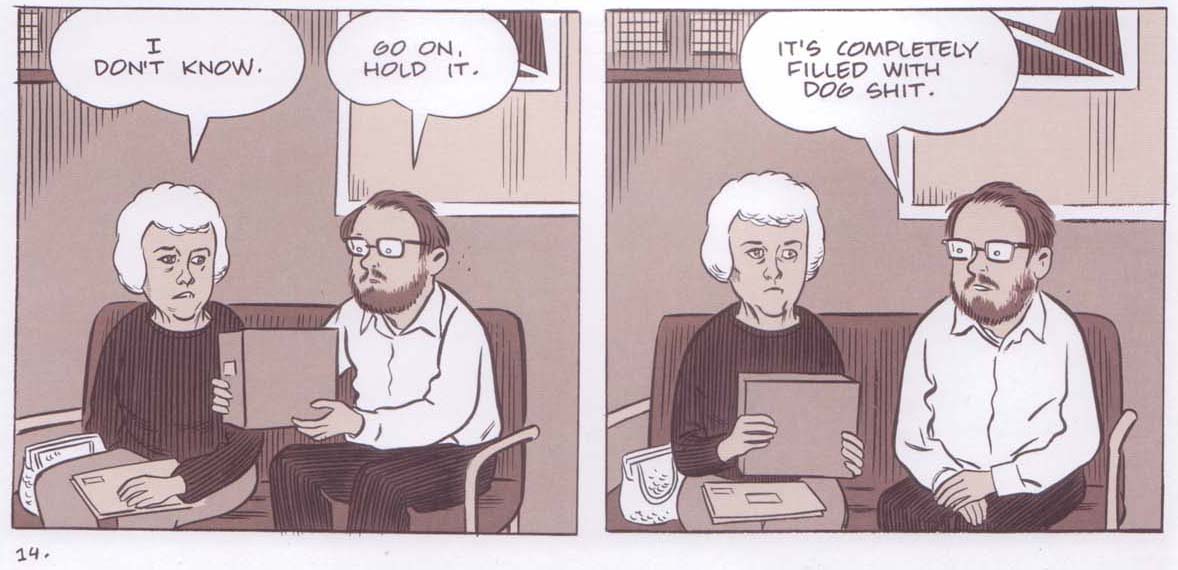

Similarly, I’m sure the Freudian connotations of arrested development and desperate, childish bid for control are entirely intentional when Wilson sends his in-laws a giant box of dog shit. Both books present their protagonists as infantile, or in danger of, or tempted by, infantilization. Both books in turn, link their own medium of comics to that same infantilization. The narratives then become engines for demonstrating and reveling their own childishness, while simultaneously disavowing it.

Both the reveling and the disavowal are accomplished in no small part by making comics women, and then killing them. As Clowes is I’m sure well-aware, a fetish is technically a displaced symbol of the mother. Barbara as collectible, then, functions as a doubly referring, vacillating system, feminizing comics and comicizing femininity. Again, the final image of Clay, armless and legless, trying to draw on a pad with a pencil in his teeth while his monstrous fish girlfriend declares her love, fits neatly here.

It’s a masochistic, self-pitying vision of comics artist as child — distanced both through its own adult violence and through its vision of the femininity as monstrous. Similarly, Barbara’s brutal death is commanded by a young girl who spins out the stories that are used in the fetish film. The comic, then, is, Clowes tells us, under the control of a feminine infant — whose whims result in very adult violence and femicide. The narrative’s grown-upness is guaranteed by the fact that it makes sexualized violence out of a child’s story.

In Wilson, Clowes actually self-reflexively acknowledges the comics own investment in female degradation. Wilson insists that Pippi, after leaving him, ended up on the streets, in a life of prostitution and drug use. She keeps telling him that much of this is not true, but he either doesn’t believe her, or doesn’t want to listen to her.

In the terms of the narrative, Wilson wants Pippi to have fallen apart after she left him because he wants her to have made the wrong decision. But the comic itself seems to have its own motivations. Yet, despite all her denials, Pippi does in fact die of a drug overdose. Clowes, like Wilson, it seems, just can’t quite resist the idea of Pippi, or Barbara, humiliated and dead. And no wonder; violence, sex, perversion, death — everything that separates Clowes from Charles Schulz, or from the infantilized medium of comics, is neatly summarized in the image of a woman’s corpse. If, Bloomian poets must kill their fathers to replace them, Clowes suggests that serious comics creators must kill their mothers to escape them. Genius comes out of her grave.

So…I was chatting on twitter with someone who was saying that he feels like there’s not a lot of in depth criticism of Clowes. I feel like that can’t be right…but then I’m not absolutely sure. So…anyone have links or refs to good Clowes crit?

I found this extensive Ken Parile piece on Ice Haven which (like all of Ken’s stuff) looks quite good:

http://blogflumer.blogspot.com/2009/12/book-of-decade.html

Any other suggestions?

Dan Raeburn’s “The Fallen World of Daniel Clowes” (Imp #1)?

PDF available at http://danielraeburn.com

[Yikes, this one really go away from me.]

Thanks, Noah, for this great post. I had never thought much about linking gender and comics per se in Clowes’ work, but you make a strong case, especially for Velvet Glove.

Over the years, I have only presented a few papers that touch on Clowes, usually in the context of broader claims. But I tend to agree with you that his work goes out of its way to thematize the artist’s and/or the story’s struggle against comics themselves – against a form that, as Clowes presents it, seems unable to encompass interior states, unable to escape its own theatricality and artificiality, unable to circumvent its own closed system of beginnings and endings, set-ups and punch-lines. Clowes dramatizes his contest with these limits, transforming that contest into the content of his graphic novels.

Take Wilson, for example. The sense of connection, of understanding, of interiority, of history that the Clowes’ characters – mainly, Wilson – repeatedly say that they want are always thwarted by the protagonist’s unwillingness to stop talking, by his demand that other people – especially women – shut up. It would be easy to see this as a feature of Clowes’ misanthropic creation: a man too horrifically self-involved to see his own villainy. But on the page itself, this solipsism is most visibly as a series of qualities endemic to comics: the obscuring and endless series of word balloons; the need to keep talking, running an externalized and insuperable inner monologue; the infantilizing and ironizing iconography; the truncated and isolating nature of the comics page itself (and few long-form cartoonists seems as wedded to the idea of comics as a collection of discrete pages as Clowes).

Indeed, it is the rigid nature of the page – imposing its own unavoidable sense of beginnings and endings – that most circumscribes Wilson’s exploration of human connection and meaning. At least in this volume, no matter what one says or sees, the ultimate reality is that any particular page must come to an end, must toss the reader back outside the work, and must, to some extent, deflate anything that might count as narrative. No matter what one encounters in the middle of the strip, it must always end when the page and its panels run out. For Wilson, this means ending with a joke. But in Clowes’ world, the deflationary punch-line and the structure of the Sunday funnies are just shorthand for the fragmented, one-page-at-a-time and one-damn-page-after-another nature of comics overall.

In Wilson, it is comics that keeps you talking, and it is comics – at least as Clowes represents them – that shuts you up. The form of comics lends its stamp to the structures of your thought (“Insert ass-rape joke here”) and to, it seems, how Clowes can represent — or not represent — thinking. (At last year’s conference at the University of Chicago, Clowes told the audience that he now tends to experience his own life in one-page segments.) I’m not trying to say that Clowes hates comics, of course; he clearly loves them. But as much as anything, he seems to be infatuated with the conflict that he has with the medium – with its history (or you argue, Noah) and with its historically inflected structure.

The most common last-panel punch-lines in Wilson involve excrement, and three different times those joke involves shit that is boxed and mailed. Perhaps that is the ultimately stand in for what comics can give you. That final delivery always comes, promising a special message. But it always comes out as dog poop.

” I’m not trying to say that Clowes hates comics, of course; he clearly loves them.”

It seems like both love and hate, maybe.

There’s a certain masochism to it — in the way he shackles himself so visible (and sweatily) to genre, structure, ugliness.

And thanks for that great comment Peter.

It’s…difficult for me to talk about Wilson without getting kind of angry. I really, really dislike it. It’s up there with Shadow of No Towers as one of the worst comics I’ve ever read, I think.

You get at why in your discussion, I think. Comics in Wilson are presented as inherently debased, it seems like; it’s almost like the medium forces cruelty and a lack of empathy. And the comics that are especially referenced here are Peanuts. Which are, I’d argue, just infinitely more empathetic and funny and imaginative than Wilson is. It feels like he’s taking Charles Schulz, turning it into a mundane lit fic bore, and then blaming Schulz for it — or, even worse, praising Schulz for the true “adult” content which Clowes has unearthed.

I just want alt comics folks to leave Schulz alone, basically. Nothing good ever comes of it when they screw with him. Superhero parodies work a lot better (Clowe’s Death Ray is my favorite thing of his I think — which isn’t saying all that much, but still.)

Agreement here on Death Ray.

The dark and debased Schulz is clearly the standard reading of Peanuts nowadays, although I’m not sure when it started. Perhaps in 1963, with Umberto Eco identifying the children of the strip as “monsters” (although of a very particular kind)? [And Schulz too focused occasionally on his strip’s cruelty.] But it would be interesting to track the rise of that idea as it percolated through the criticism.

I wrote about why the hipster vision of Schulz is an atrocity a while back.

Calvin and Hobbes’ version of Schulz is kind of impoverished too, in a way, but it’s a lot better than Wilson….

Also…it’s worth pointing out that Schulz’s strip was at least as focused on female characters as on male ones; it just did not have the kind of univocal male perspective that you see in Wilson or a lot of supposedly Schulz like alt comics (though Ware has been trying to get away from that, right? I haven’t read Building Stories…)

Parille’s piece on David Boring is also very good (can be found in the Comics Studies Reader, as well as its original location—TCJ?). Wilson is pretty horrible…I agree with that.

One good re-visioning of Peanuts is the Kafka mashup in Masterpiece Comics.. “Good Ol’ Gregor Brown” by R. Sikoryak.

http://www.cs.utsa.edu/~wagner/creative_writing/metamorphosis/gregor.html

Yes; that Kafka mash up is great. Manages to get at Schulz’s humor and zaniness in a way alt comics versions often don’t really bother with.

And I can’t find the Parille essay online; it’s also in the Best American Comics Criticism book edited by Ben Schwartz.

Here’s Noah on Ghost World in case anyone is inclined to take this seriously:

“The fetish here seems to be sadism… [Clowes] seems to be getting off on controlling Enid, or on having her be empty and filling that space… It’s really unpleasant if you believe that denying women (or anyone) their humanity is morally wrong.”

“Yet, despite all her denials, Pippi does in fact die of a drug overdose. Clowes, like Wilson, it seems, just can’t quite resist the idea of Pippi, or Barbara, humiliated and dead.”

Wilson’s ex’s death of a drug overdose doesn’t come across as validating his earlier insistence that she must have done drugs before, but as her turning to drugs in the wake of his kidnapping her and their daughter. The interest here is in showing Wilson being self-absorbed and destructive.

“Wilson’s ex’s death of a drug overdose doesn’t come across as validating his earlier insistence that she must have done drugs before, but as her turning to drugs in the wake of his kidnapping her and their daughter. The interest here is in showing Wilson being self-absorbed and destructive.”

I think Clowes is a good bit more ambiguous and complicated than you’re allowing for here. He’s always fascinated with lies and appearances. We don’t know whether Pippi was lying or not before. I’m pretty sure we’re not supposed to know.

I agree that Pippi’s degradation and death is mostly about illuminating Wilson’s psychodrama. That seems kind of problematic to me, inasmuch as, you know, women are people too, not just appendages to men’s inner angst. (Which is why it’s so important that Peanuts is *not* (only) about Charlie Brown’s sadness, but insistently shows us life, and angst, from the perspective of Lucy, Sally, Peppermint Patty, and Marcy as well.)

Here’s the Ghost World essay deelish quotes, in case folks want to read the whole thing.

But Wilson is consistently shown as oblivious to the reality of other people. Also, note Wilson’s ex’s depression in the scene by the pool, both as groundwork for her turning to drugs (making Wilson’s assumption a self-fulfilling prophecy) and one of many cases in which the perspectives of Wilson’s victims are portrayed.

And just using common sense: why would Pippi admit to a past of prostitution but lie about drug use?

This insistence on making every Clowes comic the work of a sadist demonically bent on torturing women beneath the guise of superficially self-deprecating narratives is an interesting contrast to your polite, circumspect responses to Alan Moore’s many variations on the theme of loving the rape monster.

Pippi did say that she wasn’t “on the street,” right? Not sure what exactly that means, though. I thought street-walking; could mean homeless.

Otherwise… zing!

Actually, if you read my Lost Girls review, you’ll find that I think that that’s an extremely problematic comic. And I’ve stopped reading the LOEG for the most part for similar reasons. I think Moore struggles with these issues, sometimes successfully, sometimes much less so. I think the treatment of Evey in V for Vendetta is pretty much a disaster, and really quite offensive.

And my recent post on Watchmen is about how Moore sometimes gets in the same trap as Clowes…that is, using violence and degradation as a way to demonstrate his distance from his source material so he can lay claim to “realism”.

I like Moore a lot more than Clowes, but that doesn’t mean I think Moore is perfect. I’ve written a lot about my problems with his work. (Not that you should read everything I write or anything, of course.)

“And just using common sense: why would Pippi admit to a past of prostitution but lie about drug use?”

As Peter says, it’s not exactly clear she does admit to the prostitution. Also, people are complicated; making common sense judgments about what they would or would not say in x circumstance maybe tells us what you (think you) would do in similar circumstances, but isn’t especially helpful otherwise.

We don’t learn enough about Pippi’s present or past to know what she thinks about most things. Is she depressed because of Wilson? What’s going on in the rest of her life? We just don’t know. As with Barbara in Like a Velvet Glove, she seems mostly like an opaque slate on which the protagonist and the comic can work out tropes about female degradation.

Just had a chance to look at my copy: Pippi’s time as a prostitute is never disputed by her or in any way. Wilson makes a point of adding florid details about drug use and homelessness, which she does repeatedly deny. So her overdose makes more sense as irony- she finally turns to drugs after her kidnapping- than as confirming his notions, which wouldn’t even constitute a joke.

The problem with claiming that Clowes treats people, and particularly women, as dehumanized appendages to Wilson is that Wilson’s egocentrism and total lack of consideration are features of the story- text, not subtext- and the women he encounters are subtly but deliberately shown having to cope with that. He meets his ex at a point where she’s pulled herself together and she spirals into self-destruction after his intervention. The lady who cared for his dog makes a grim compromise in partnering with him. His daughter reaches out to him but has to hold him at arm’s length. A dehumanizing treatment wouldn’t show any of those things. An exercise in tropes of female degradation would show the details Wilson makes up for his ex rather than making an issue of his doing that. Again, you take a negative aspect that is a subject of the work and hurl it at Clowes with a kind of thudding, vindictive literalism.

As for Moore, you’re speaking more strongly now than you have before, but the prim assessment that he tries and sometimes fails to deal successfully with the abuse of women seems inadequate to the problems in his work- even calling V for Vendetta a disaster makes it sound like an accident- and you don’t need the kind of creativity to perceive them that you rely on for demonizing Clowes.

Did you read any of the links? I’ve repeatedly talked about problems with Moore. Like, I have multiple essays about them. Read the comments section to Isaac Butler’s post from hate fest; I make my problems with V very clear (as in, I spend considerable time defending Isaac’s very reasonable argument that it’s the worst comic ever).

And yes, I think he’s a better creator than Clowes. Because, you know, he is.

It’s certainly the case that Wilson is about Wilson’s egocentrism. However, just because that’s what it’s about doesn’t mean that that’s not what it’s about. The smug insistence that Wilson is a horrible person (a fairly banal observation, don’t you think?) doesn’t really erase the enthusiasm with which his consciousness is granted pride of place. Pointing out that ass rape jokes about prison are dumb…is that a condemnation of ass rape jokes? Or is it an excuse to tell the same ass rape joke over and over?

Pippi doesn’t confirm the prostitution either, as I remember (I just read it, but I could be wrong.) And…again, I don’t entirely understand why you think that flattening out Clowes’ narrative and robbing it of ambiguity is defending him. But perhaps you’re not defending him? I guess you could be telling me that I’m giving him too much credit….

Hi deelish,

Looked again myself: the “on the street” reference is definitely about homelessness. But the only confirmation we have about prostitution, to my eyes, is the “D.A.D.D.Y. Big-Dick” joke.

And not that it matters much, but I never felt that Pippi saw herself as a kidnapping victim — just that she found herself involved in Wilson’s kidnapping of her/their daughter. It was more “this kidnapping” (her words) than “my kidnapping.”

But in the end, I can’t find that Wilson cares any more about exposing or exploring Wilson’s misogyny, misanthropy, or narcissism than the inner lives of any of Clowes’ characters. Wilson, too, seems trapped in someone else’s pre-set script and structure of pathology. And as far as I can tell, that structure — the bars of Wilson’s cage, so to speak — is the form of the comics page, itself, and its narrative/generic constraints. The only drama here is Clowes kidnapping of — or his rage at being kidnapped by — Schulz.

Peter

Right…and we don’t actually know if she has that tattoo or if Wilson is just being a jerk. We don’t see it, and he’s not precisely a reliable narrator.

Yes…I misattributed, I think. It’s not in the Comics Studies Reader, but the BACC (the Parille essay about David Boring, that is).

Noah, a comparison of your writing on Clowes and Moore is revealing because you cherrypick isolated cues and concoct weird, intricate readings to paint Clowes as a sadistic misogynist while being restrained and generous when Moore gives you an avalanche of material for just such a reading. It’s like playing bad psychiatrist to one patient while another is chopping Jack Nicholson-style through your door. I’m not saying you should apply your Clowes treatment to Moore; it’s not appropriate or even necessary, because with Moore you can just focus on the work without getting into the kind of personal speculation and fantasy that you confuse with criticism of Clowes.

“My recent post on Watchmen is about how Moore sometimes gets in the same trap as Clowes…that is, using violence and degradation as a way to demonstrate his distance from his source material so he can lay claim to “realism”.”

That post is about Moore using homosexuality as a signifier of adulthood in Watchmen; not a word about violence against women, or much of anything other than his inclusion of gay characters in that comic.

Here are examples of what I mean. I’ve never seen you write a line about Moore like: “Clowes, like Wilson, just can’t quite resist the idea of Pippi, or Barbara [Velvet Glove], humiliated and dead,” or “The fetish here seems to be sadism… [Clowes] seems to be getting off on controlling Enid, or on having her be empty and filling that space,” or about Ghost World being a “basic rape fantasy.” Even this: “Much of the adult/edgy content, misanthropy, and violence against women in his books comes across as a kind of desperate signaling that he is not writing for children,” which would be a perfectly reasonable observation of Moore, is your opinion of Clowes.

How much violence against women is there in Clowes’ work? You cherrypick two cases: the heroine/love interest’s murder in a snuff film in Velvet Glove, and Wilson’s ex Pippi’s death of a drug overdose.

Barbara is murdered in Velvet Glove, but a careful reader might observe that the male hero gets his arms and legs torn off. Clowes isn’t callous to the female characters: Barbara is a mysterious, noir-style femme fatale, but her mystery and her suicidal fatalism at least suggest the existence of a person. Her death is shocking and brutal, her grave is the site of the showdown and the last image- she is not casually discarded. Tina and her mother are menacing images of femininity who threaten to smother Clay, but they’re also portrayed with obvious pathos and compassion. There are several negative male archetypes: the violent cops, the jeering fratboy who kills Barbara, and the hairy, shirtless, testosterone-injecting hitman (whom you interpret as an “adolescent power fantasy!”) It’s a weird, dark book, but you have to read it very selectively to find an emphasis on violence or animosity to women.

In Wilson, Wilson’s ex Pippi dies offstage of a drug overdose. You say,

“In Wilson, Clowes actually self-reflexively acknowledges the comics own investment in female degradation. Wilson insists that Pippi, after leaving him, ended up on the streets, in a life of prostitution and drug use. She keeps telling him that much of this is not true, but he either doesn’t believe her, or doesn’t want to listen to her… Yet, despite all her denials, Pippi does in fact die of a drug overdose. Clowes, like Wilson, it seems, just can’t quite resist the idea of Pippi, or Barbara, humiliated and dead.”

This is stupid. Clowes makes a point of having Wilson floridly describe Pippi’s supposed past of drug addiction, and her repeatedly denying it. However, her past as a prostitute is never questioned. Also, Wilson is a jerk. Those points should tell you he is fantasizing for his own gratification. Wilson then enlists Pippi in kidnapping their adopted, biological daughter (whether Pippi is his prisoner or accomplice is unclear). During this experience, Pippi expresses depression and horror at this artificial family until she runs and turns Wilson in. All that suggests that Wilson’s fantasies about her drug use became an ironic, self-fulfilling prophecy when she really turns to drugs as a consequence of his intervention. She’s on the mend when she meets him and she falls apart because of him. When he learns this, his “I knew it!” shows he is oblivious. If “Clowes can’t resist the idea” of a female character “humiliated and dead,” or the comic is “invested in female degradation,” something more than an offstage death that implicates the antihero is needed. What about the other women in the book? Wilson cohabits with a woman in desperate straits who toughens up and distances herself from him with dignity. Wilson’s goth teenage daughter grows up, creates a real family, and compassionately reaches out to him. Is this a comic someone who “couldn’t resist the idea of a woman humiliated and dead” would make?

Then there’s your reading of Ghost World: Clowes is a diabolical puppet master who drew himself as a pathetic, middle-aged pervert for the sake of self-glorification and an expression of power over Enid.

https://www.hoodedutilitarian.com/2009/12/somebody-elses-ghost-ghost-world-roundtable/

He continues gleefully demonstrating this power in coded compositions throughout the book. I wouldn’t have thought a panel of Enid and Becky looking at a newspaper in the restaurant was doing that, but yep.

https://www.hoodedutilitarian.com/2012/01/what-does-that-even-mean/

When female characters are comparatively minimally sketched in Wilson, they’re “opaque slates to work out tropes of female degradation” minimized by Wilson’s heroic consciousness. When Clowes writes rounded, central female characters who express his own thoughts and feelings in Ghost World, the phenomenon of an author identifying with his characters (“Madame Bovary, c’est moi”) becomes a form of sexual assault:

“The fetish here seems to be sadism… [Clowes] seems to be getting off on controlling Enid, or on having her be empty and filling that space… It’s really unpleasant if you believe that denying women (or anyone) their humanity is morally wrong.”

“Sadism is about control. As such, it’s often about fantasies of actually inhabiting or being the other person. So imagining someone as your alter ego can be a way to inhabit them and destroy them. Basic rape fantasy.”

Now, it’s difficult to even think of a Moore comic that doesn’t revolve around a shocking act of sexual violence against women. Whatever other purposes those events play in their different comics, Moore undeniably relies on the trope to signal adulthood; think of Batgirl crippled by the Joker, or Sally Jupiter attacked next to all those goofy supervillain trophies. Then there’s a weirder theme: do the women really have to show so much love for the Comedian at the end of Watchmen? Does Evey have to thank V for her treatment while showing all the signs of a sane, empowered woman? Does Neonomicon’s heroine have to befriend and engage in cute sex play with her rapist fish monster?

So after Clowes, let’s see you the hell you unleash on Moore:

“I think Moore often handles sexual assault thoughtfully, and I think he is very much a feminist… but I don’t think it’s crazy to suggest that Moore lost the occasional fall with sexism.”

“Moore’s a complicated guy and his art struggles with these issues throughout his career. I don’t think the fact that he fails on occasion makes him a bad human being. It just makes him a human being, period.”

https://www.hoodedutilitarian.com/2012/09/v-for-vile/

“Watchmen is one of my favorite comics. That doesn’t mean it’s perfect in every way, though.”

https://www.hoodedutilitarian.com/2013/06/homosexuality-will-make-your-comic-real/

Mew.

The piece about Moore is about how he uses homosexulaity exploitively as a signfier of adulthood. But you’re mad because I didn’t make the criticisms of him you want me to make, or whatever.

I like Moore better than Clowes in general. I think his handling of gender issues is more thoughtful in general, though there are still problems. If you want that to mean I’m unfair and biased…well, sure. I’m biased. I like Moore better than Clowes. I don’t think I made a secret of that.

I think the treatment of Evey’s conversion/rape is pretty awful, and the main reason Isaac’s statement that V is the worst comic ever is reasonable. The Killing Joke is kind of crap, and the crippling of Barbara Gordon is offensive and stupid. I think the treatment of the female characters in Watchmen and Swamp Thing and some of his other comics are really sensitive and thoughtful. The inclusion of sexual violence or themes of sexual violence is not necessarily anti-feminist (if it were, Susan Brownmiller would be an anti-feminist, which she is not.)

I don’t know. I’m willing to say a lot of Moore is really problematic, and to print lots of harsh criticisms of him. Yet, because I like Clowes less and you like Moore less, somehow that’s a sign that I’m…what? Evil? A bad critic? Morally horrible?

I don’t find your defenses of Clowes especially thoughtful or convincing…but that’s fine. Different strokes.

You can reprove Moore all you want here. My point is, you haven’t pursued him in the same way, really grasping at straws with Clowes while Moore gives you bales. This makes it hard to believe that your line with Clowes is really a white knight kind of thing.

You only think I’m grasping at straws with Clowes because you think I’m wrong! It’s not that I’m unfair; you just disagree with me.

Really, I don’t think there’s another site that has published as harsh criticism of Moore as we have. I’ve published pieces saying V and Watchmen are the worst comics ever; I wrote an extended takedown of Lost Girls; I’ve written myself about why V is a mess; I published Jeet’s comment about why Watchmen sucks. I really, truly think Killing Joke is a piece of shit; I haven’t written about it at any length because I don’t want to reread it mostly.

There’s been a lot of pro-Moore stuff too…but there’s been quite a bit of positive commentary about Clowes on this site as well (one just this week.) I’m sorry; it just seems like you’re butt-hurt because I don’t like this guy you love, and no matter how much ground I give in other respects, you’re still determined to be butt-hurt. Which is your right as a critic…but I think at this point the conversation isn’t going to go anywhere else productive, so I’m going to try to disengage. We’ll see how that goes….

But of the posts you’re talking about, you only wrote two comparatively sane and mild pieces. (No “Again, Moore can’t resist…” “Clearly, Moore’s fetish is sadism…”) Sure, you’ve /published/ tough criticism of Moore, /published/ a nice blurb on Clowes… I’m not talking about that. I’m talking about your criticism. I don’t care whether you like Clowes’ work. I’m not trying to sell you on it. My subject is these accusations of symbolic rape, sadism, and abuse of women. Critics are not exempt from criticism. You can feel free to stop answering me, it’s not like Clowes is engaging you.

And I’ll say one more time; I find Clowes’ work more problematic than Moore’s in lots of ways.

Moore definitely has more representations of explicit violence against women. In part that’s because he’s pulp; in part, though, I think it’s because he’s more open about engaging violence against women as an issue. Clowes’ take is more deferred and low key…but that doesn’t necessarily make it better. Kind of the reverse, in my view.

And right, Clowes absolutely doesn’t engage me! There’s an outside chance that he has some vague idea who I am, but I wouldn’t bet on it.

And… “butt-hurt”? Gender theorist, heal thyself.

Moore openly engages with abuse of women. It’s well-meaning. There’s also a cheap, excessive reliance on it to be shocking, adult, and drive the pulp narrative… His female characters are not very interesting. There’s a theme of recovery from trauma, but often in the care of a dominating male figure. Usually with really didactic, reader-steering work like his the subtext is going to be something fierce. I think the problem with V is to do with the dark side of that hippie, new age culture. And the passages I mentioned that suggest to me that he doesn’t quite understand rape as well as he should for a guy who thinks he’s got the cure, you know?

I get that subtle themes can be worse than open confrontation. That’s why Crumb’s misogynist themes don’t bother me so much because he makes his problems his subject. But there’s subtle and then there’s the Illuminati, Da Vinci Code shit you’re selling with Clowes.

“His female characters are not very interesting. ”

I find Surprema to be very interesting.

I don’t think Tom Strong, Tomorrow Stories, Promethea or Top 10 really fit the narrative you are trying to make.

Big Numbers doesn’t either… though it’s obviously an incomplete work.

Mina in League has recovered from trauma, but there’s clearly no dominating male figure… she’s the team leader, unoffically at first and officially later on.

And actually thinking of Laurie in Watchmen- it’s pretty bizarre to call Dan “dominating” considering how meek he is.

And Laurie’s mom never has a dominating figure helping her recover from trauma- she’s single as an old woman.

Are you just pretending every Moore book is like V for Vendetta?

I was also thinking of the Rite of Spring issue of Swamp Thing and the way Dr. Manhattan (emotionally immature to that point) gets to lecture Laurie at the end of the Mars chapter. I’m not crazy about the way that issue has the saving grace of humanity hinge on the miracle of Sally and the Comedian also having had consensual sex, or how the mother and daughter’s character arcs come down to embracing the Comedian. That ABC stuff is a different kettle of fish from the mature superhero thing. I didn’t read much of it.

Despite the fact that there is much to recommend Promethea in terms of its female characters, I still think that Moore totally botches the central relationship between Sophie and her pal Stacia. It just doesn’t ring true to me and borders on painful in places. As far back as Halo Jones it seems as if Moore has been trying to present friendships between young women that are as believable and lived-in as Jaime Hernandez’s Locas cast and he just doesn’t seem to be able to do it.

I really like Halo Jones…and think that female/female friendships are nicely done there.

I found Promethea kind of unreadable after the first few issues, so can’t comment on that….

Abby isn’t really presented as traumatized, nor is Rites of Spring a recovery from trauma, really…Swamp Thing is presented as more traumatized than Abby in a lot of ways I’d say….

Oh I definitely liked Halo Jones. It’s great fun and I wish he’d done more with it. I just think he utterly failed in his stated goal of doing a rip-off of Love and Rockets.

Did he say that’s what he was doing? I don’t doubt it for Promethea…

I thought the female soldiers, and the reversal of gender roles, was very nicely done, and the death of Halo’s friend was really painful. Halo’s relationship with the general was great too…I dunno. It’s been a while since I read it, but I wouldn’t say his treatment of female characters or female friendships in that book was a failure.

Yeah, he did say that about HJ though I honestly don’t remember where. I thought it was in one of the intros to the Titan collections, but I haven’t been able to find it.

“Despite the fact that there is much to recommend Promethea in terms of its female characters, I still think that Moore totally botches the central relationship between Sophie and her pal Stacia. “-

I’ve read criticism about the depiction of Sophie in Promethea before. For me, I just see Sophie as a stand in for the reader. Sophie’s name means “wisdom” and basically she learns magic in the series through her kaballah journey and initially from being mentored by the former Prometheas and the wizard dude, Faust. And of course as she is being educated we the reader are as well.

As a character in her own right she’s not overly interesting, I don’t think she does anything really dynamic until the very end of the series when she goes on the run from the FBI.

I don’t think there’s anything offensive about her or anything, she’s just not that exciting a character. And her friend, Stacia, is somewhat dropped towards the end as a character. Neither character is really shown having much of a social life except as it really relates to the plot.

Fair enough, and indeed, the same could be said for Halo Jones I suppose. As I recall, that was an aspect of the character that was mentioned in the framing sequence, that basically she could have been anyone.

I don’t think attacking another writer is a helpful way to respond to charges of misogyny against Clowes. Berlatsky draws a valid connection between Velvet Glove and Wilson when he points out that both are about a man on a quest to rescue a woman from degradation. I hadn’t thought of that connection before. But once you’ve observed that similarity, then you have to observe the differences. Clay in Velvet Glove is pursuing a self-destructive, noir femme fatale and he gets destroyed himself in the end, pretty much. Wilson is creating his own narrative of female degradation, perceives himself as being on a quest to rescue his old flame, and clearly takes satisfaction in it. And he winds up destroying her without realizing it. I don’t think you can read Wilson very carefully and not come away with that conclusion. Velvet Glove is an exercise in noir tropes and Wilson is about a guy who loves that kind of narrative and makes it a reality for the woman he’s pursuing. And that dynamic alone should be a signal that Clowes is writing and thinking about misogyny, not simply expressing it. Arguably, both narratives are unreliable because Velvet Glove is surreal and Wilson is a self-absorbed loser.

Thanks; that’s an interesting take.

I think the narrator, and narrative in Clowes is just about always unreliable.