When I sit in my chair and and listen to the author speak, his or her voice carries me to a place of imagination. In many cases this experience helps put the listener into a frame of mind to absorb the work. Hearing the words with the author’s own inflection, tone and cadence has a transformative effect on the text.

When I sit in my chair and and listen to the author speak, his or her voice carries me to a place of imagination. In many cases this experience helps put the listener into a frame of mind to absorb the work. Hearing the words with the author’s own inflection, tone and cadence has a transformative effect on the text.

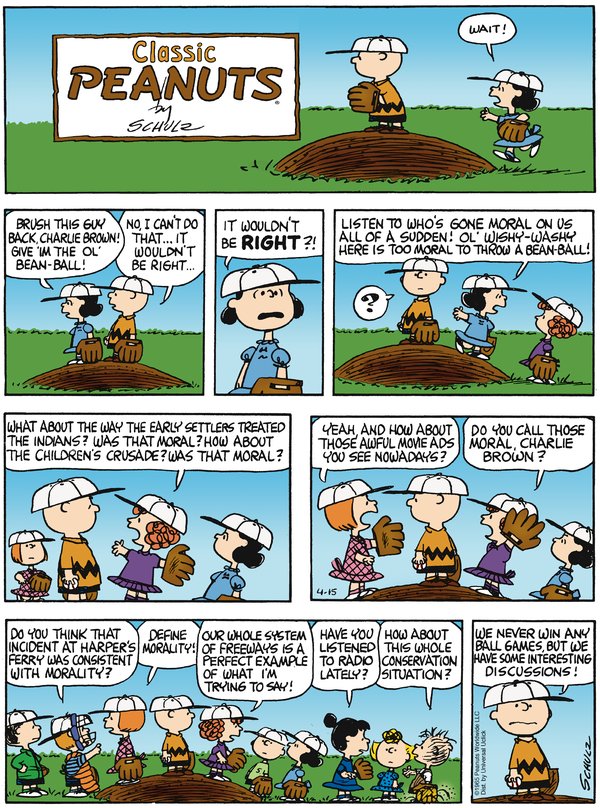

In comics, the imagery is a literal part of the text. Image. Imagination.

The role that author readings fill in the experience of consuming prose is that of a facilitator. It serves to help guide the reader further into the author’s imagination. As they say, ninety percent of communication is through voice and facial response. Author public readings can enhance the audience’s relationship with the text.

In comics, one notices, the author’s imagery is already an aspect of the text.

What I find instead is redundancy and overstatement of the author’s worldview by placing the images upon the screen and also acting them out. Comics are, of course, a subgenre of the literary form drama. Drama, referring to plays, motion pictures: literature that is expressed through performance and acted out. While plays are acted out on the stage and motion pictures are acted out on the screen, comics are acted out on the page.

One would not attend a screening of a film and expect the director or screenwriter to be stand off to the side with a microphone, delivering all of the dialogue along with the actors. But this is what is done in comic author readings. There is an audience, a slide projector and the author not only telling the audience what is on the screen but actually reciting what is plainly spoken by the characters.

This sort of performance actually degrades the author’s own work by performing a redundancy. In trying to mimic the activities that their cousins, the print authors, undergo to create an intimacy with the audience, comics authors actually sabotage their own work. The result is a hollow imitation of both comics and prose.

The reason that these public readings enhance the experience for prose audiences is that they help guide the audience into a sense of an author’s imagination–an entirely new dimension to the work. The reason that public readings are corrosive to comics is that this extra dimension of immersion is actually competing for the audience’s attention against comics’ innate best attribute which is imagery itself.

_________

Image from Guy Delisle’s Jerusalem