This is the first of a two part essay. Part 2 is here.

__________________

Anyone who has heard of Before Watchmen probably knows something about the related controversy even if they haven’t read a single issue of the series. Despite attempts by DC to present the series as the official prequels to Alan Moore’s and Dave Gibbons’ mid-1980s classic Watchmen, many fans of the original have questioned the necessity and legitimacy of the prequels. It didn’t help DC’s credibility much that both Moore and Gibbons have spoken out against the series. Moore fiercely denounced it as a cynical exercise in greed and stupidity (e.g. Amacker), while Gibbons described it as being “really not canon” (Yin-Poole par.17).[i] After ten months, nine titles and 37 issues, the series finally ended in April with the publication of the final issue. However, this probably isn’t the last we have heard of Before Watchmen: DC has scheduled to relaunch the series in a four-volume collector’s edition in June and July.

While the series might not have been the unequivocal success that DC was banking on, one creator seems to have risen above the controversy to receive both popular and critical adulation. The creator’s name is Darwyn Cooke. Cooke is writer and artist of the six-issue Minutemen, and writer of the four-issue Silk Spectre, illustrated by artist Amanda Conner. A survey of the major reviews of Minutemen and Silk Spectre reveals that almost every critic has something positive to say about them.[ii] Grant Morrison has singled them out for praise—“Amanda Conner’s stuff is brilliant … and Darwyn Cooke’s Minutemen is great” (Sneddon par.42)—and a few commentators have even gone so far as to call the books worthy additions to the Watchmen universe.[iii] About this overtly positive consensus I believe something must be said. While I agree with the majority of critics that the quality of the art work in Minutemen and Silk Spectre is beyond reproach, I have deep reservations about the tenor and preoccupations of Cooke’s writing. Given the almost universal acclaim enjoyed by Cooke’s titles and the willingness of so many critics to accept his revision as worthy of Moore and Gibbons, I believe it is important that a clear dissenting case be made.

Watchmen, Deconstruction, Reconstruction

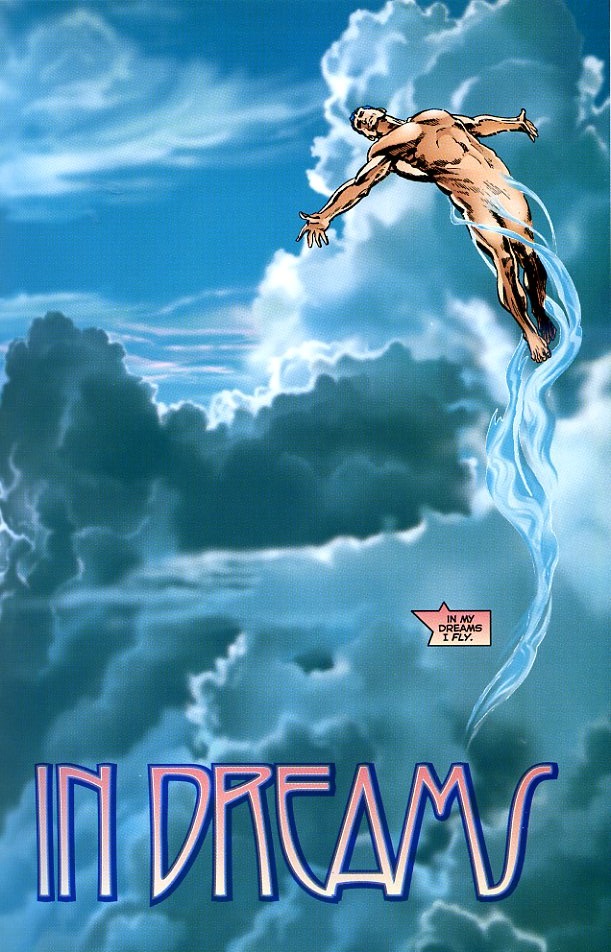

To address the problems of Cooke’s revision, it is useful to reiterate what Watchmen was “about”. Watchmen has been called a “deconstruction” of a traditional superhero comic (e.g. Thomson). While the term is overused, it still aptly summarizes the intent of Moore and Gibbons. In brief, deconstruction refers to a critical strategy aimed at exposing the unquestioned assumptions and internal contradictions in a traditional discourse. The target of Watchmen’s deconstruction is specifically the heroic power fantasy offered by traditional superhero comics. The question “Who watches the watchmen?” not only invites readers to consider the real-world implications of power abuse by “heroes” who have appointed themselves the world’s guardians, it also appeals on a meta-textual level to the same readers—those literal “watchmen” watching the pages of the story unfold—to be self-critical about their consumption of such heroic power fantasy.

And make no mistake about it: traditional superhero comics cater mostly to the heroic power fantasy of heterosexual males. Part of Moore’s and Gibbons’ campaign in Watchmen was thus to disrupt the expectations and prejudices of this dominant demographic. Instead of a linear story supporting a singular heterosexist worldview, Watchmen’s narrative is deliberately ambivalent and multilayered, including subplots, digressions, time shifts, alternate scenarios, allusions, parodies, and addendums. The intent is to challenge the monolithic notion of “heroism” and explore the richness and complexity of ordinary, unheroic lives. In addition, the book explicitly deflates the heterosexual male ego by presenting a catalogue of unheroic males. Rather than aspirational figures such as Superman, Batman, Wolverine, the readers are presented with “heroes” in the shapes of a narcissist, a rapist, a zealot, an impotent and an H-bomb. The fact that so many readers have still read some kind of fantasy antihero into Rorschach has earned an appropriately scornful response from Moore.[iv]

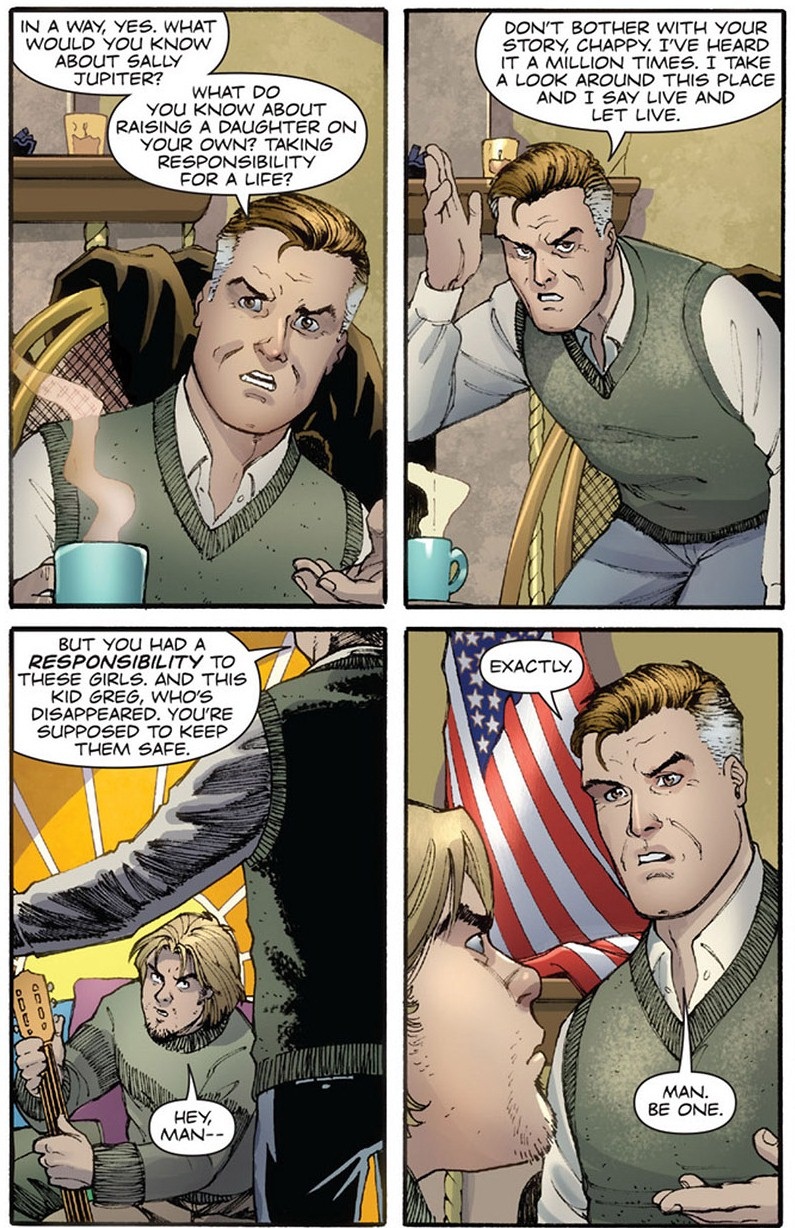

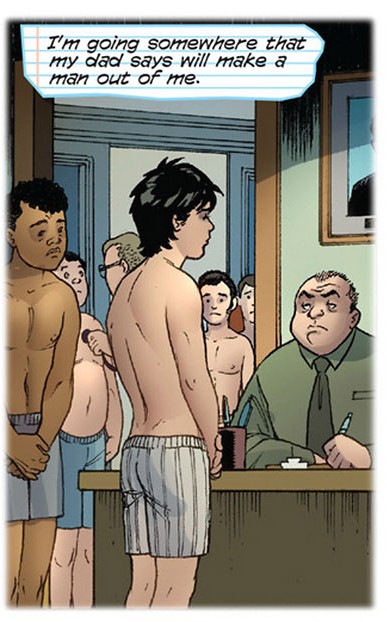

On the surface, Cooke’s projects appear to be attuned to Moore’s and Gibbons’ deconstructive spirits. He mentioned in an interview that Minutemen deal with hard-core topics such as “homosexuality, sadism, opportunism, greed, self-interest” (Truitt par.18). But then he felt the need to add this: “because it has to have it in order for me to be passionate about it, somewhere in the kernel of it is the heroic ideal” (Truitt par.18). And herein lies the problem. Cooke’s interest is not in deconstruction but in reconstruction, i.e. reaffirming the conservative, nostalgic moral paradigm of a traditional heroic power fantasy. Whereas Moore was interested in demolishing heroic stereotypes in order to explore the humanity beneath, Cooke is more interested in reinforcing stereotypes in order to prescribe for humanity what is and isn’t heroic. Under Cooke’s revision, a critique of heroic constructs has reverted to a defence of heroic constructs. This makes Minutemen and Silk Spectre, in my opinion, a diverting misappropriation at best and a grotesque travesty at worst. I have chosen to examine three areas: (i) the stereotyping of sexual minorities in Minutemen, (ii) the whitewashing of heterosexist violence in Minutemen, and (iii) the affirmation of paternal authority in Silk Spectre.

Reconstruction 1: Lesbian Martyrs and Gay Villains

The original Watchmen was ground-breaking in its depiction of sexual minorities. Moore has long been a supporter of gay rights (e.g. Gaines), and his explicit inclusion of gay characters could be seen as an expression of this support. Nevertheless, it would be a mistake to expect from Moore any didactic portrayal of gay people as “positive role models”. Moore’s gay men and women are diverse, complex and flawed—just as people are in real life. His characters aren’t one-dimensional caricatures and their individualism, autonomy and rights to exist are taken for granted.

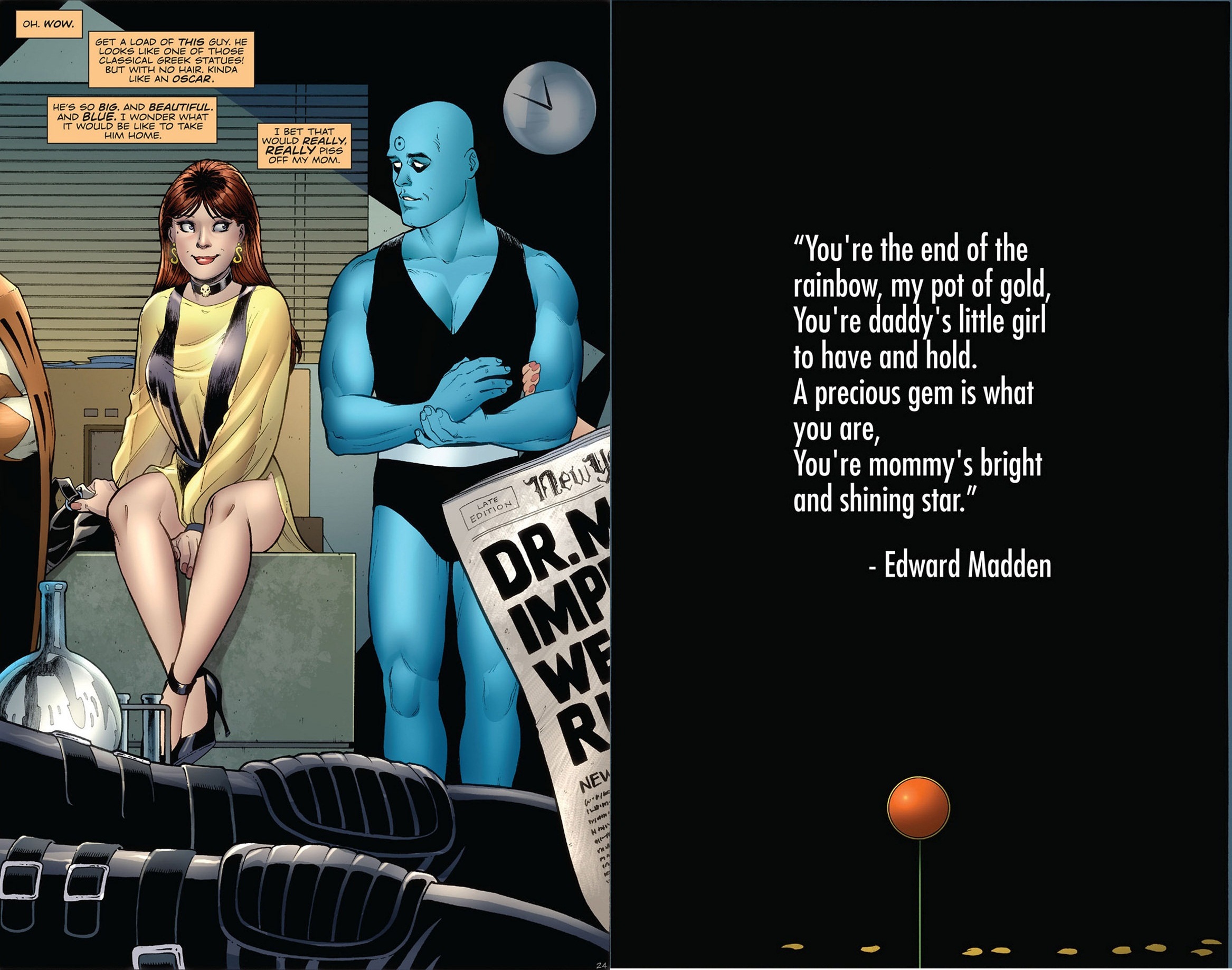

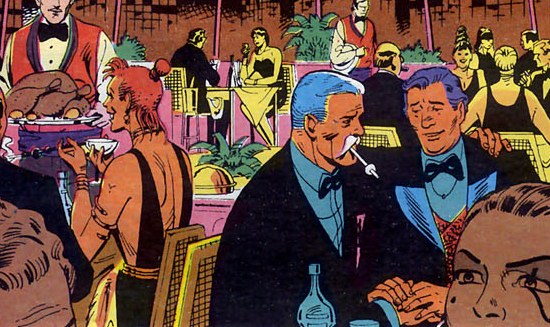

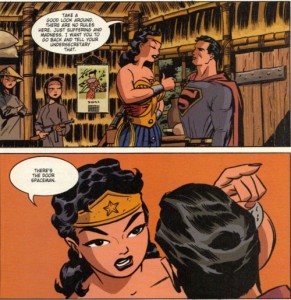

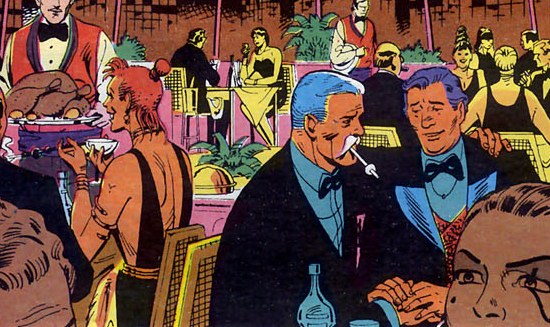

In Book 1 of Watchmen, Moore did something unprecedented in a mainstream superhero comic: he includes a normative image of a gay couple holding hands in public (Figure A1).[v]

The image explicitly normalizes homosexuality and challenges the genre’s tradition of making gay men invisible, risible or abominable. The placement of the gay diners in the midst of the “hero” and “heroine” Dan and Laurie expresses Moore’s egalitarian argument that everyone is a hero in his or her own story, and the lives of non-traditional ordinary folks are just as important as the lives of traditional superheroes.[vi]

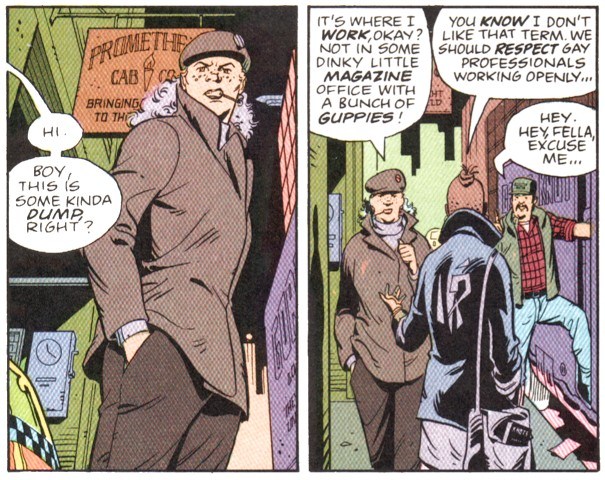

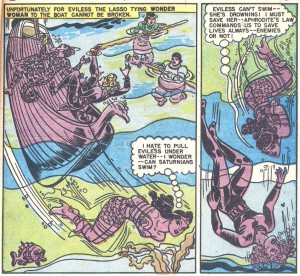

Moore took this concern further by including among his minor characters a dysfunctional lesbian couple. The remarkable thing about the couple Joey and Aline (Figure A2) is that they embody everything that traditional comic book readers are likely to find objectionable in women: loud, assertive, opinionated, and so butch-looking that people call them “fella[s]”.

Joey especially is rude, bossy, prone to violent outbursts, and even physically assaults Aline in public. Yet, by taking an interest in these women and depicting them against the “Hiroshima lovers” shadow in the context of Adrian’s alien attack (Figure A3), Moore rewrote the comic book assumption that such people are unimportant and have no rights to exist. Their deaths are a reminder that every life is a “thermodynamic miracle” and an indictment of the type of heroic ego that would justify mass murder as a master plan.

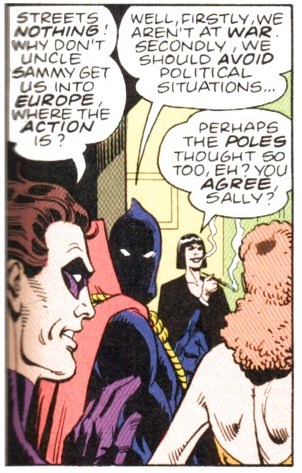

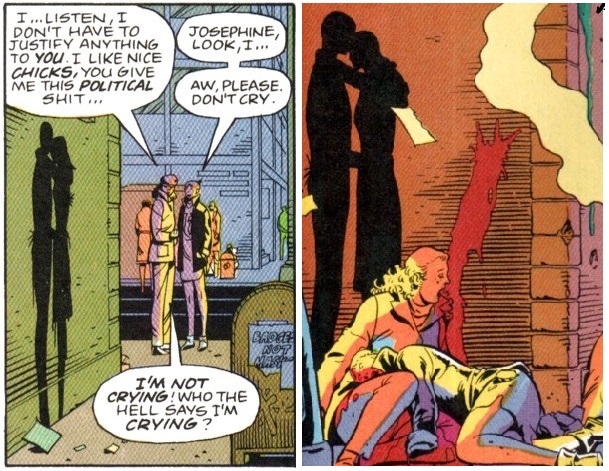

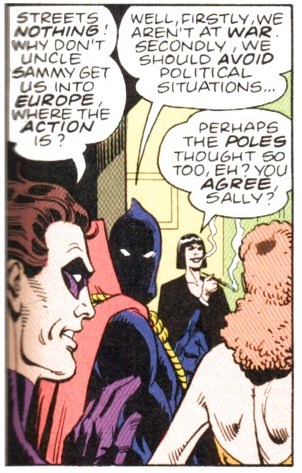

The same conviction applies to Moore’s exploration of superheroes. Rather than perpetuating the myth that superheroes are heroic heterosexuals, he saw that dressing up to fight crimes is more likely to be psychologically appealing to outcasts and minorities. Accordingly, he made three of the eight original members of the Minutemen gay. Silhouette/Ursula Zandt is the lesbian in the group. Although Ursula as a character barely exists in Watchmen, what we saw of her suggests she is the opposite of conventional. As drawn by Gibbons, she has a sharp, angular face, an androgynous haircut, wears a kinky black leotard and smokes a phallic cigarette. That her only line in the book is a sarcastic jibe about Sally’s Polish heritage (Figure A4) suggests that she wasn’t meant to conform to any “nice girl” stereotype.

Cooke said in an interview that Ursula is “the hero” of Minutemen (Truitt par.12). It is possible that his take on Ursula is inspired by the character of Valarie Page in Moore’s other masterpiece, V for Vendetta. Yet, whereas Moore had the good sense to give Valarie an independent voice and make her an inspiration to another woman, Cooke does something far less inspiring with Ursula: he refashions her into a romantic martyr and erotic fetish for straight men. He claimed without a hint of irony in the interview: “[P]eople are really going to dig her” (Truitt par.13). As drawn by Cooke, Ursula has become a petite, chicly dressed and conventionally attractive young woman (Figures A5-6), and her main function in the book is to serve as the “conscience” of Minutemen and an object of unrequited love for the straight male narrator, Hollis Mason.

In other words, Moore’s attempt to shake up the genre by challenging readers to take notice of the kinds of gay characters they wouldn’t expect to see in a superhero comic is sabotaged by Cooke in favour of a hetero-friendly paradigm about hot-looking lesbians and hot-blooded straight men. In Book 2, Ursula finds sanctuary in a Catholic church after being wounded by a stray bullet during her investigation of a paedophile ring. Had Moore written the scene, no doubt he would have recognized the Catholic Church as an institution plagued by its own child abuse problems and developed an argument that calls into question any simplistic dichotomy of “good” and “evil”. Yet, such social, historical and philosophical inquiries seem beyond the scope of the literal-minded Cooke, who piles on the religious sanctimony and romantic clichés instead (Figure A7).

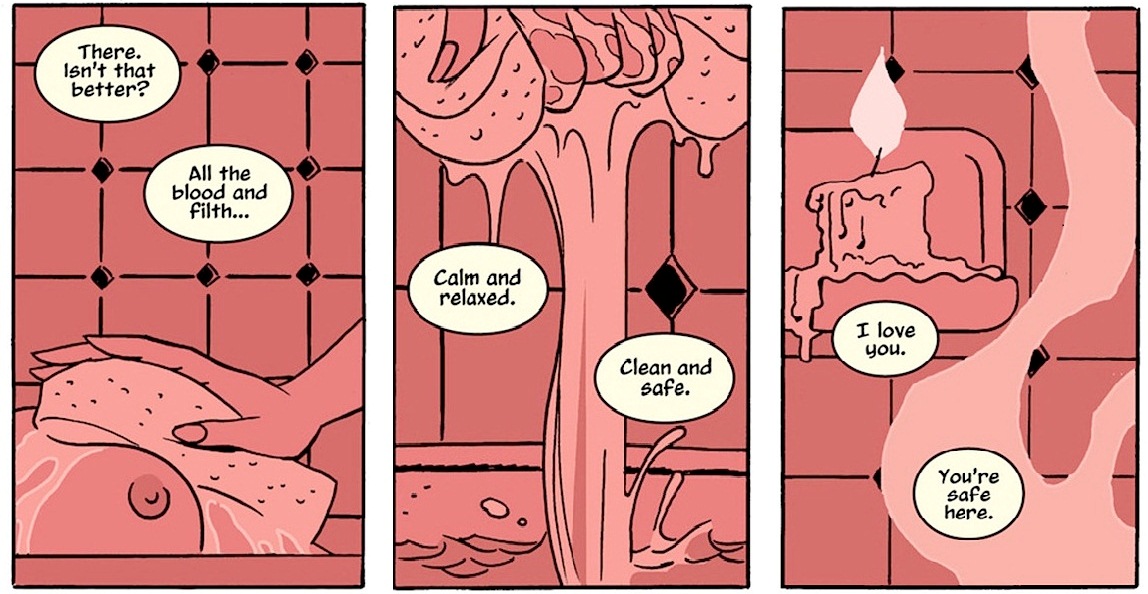

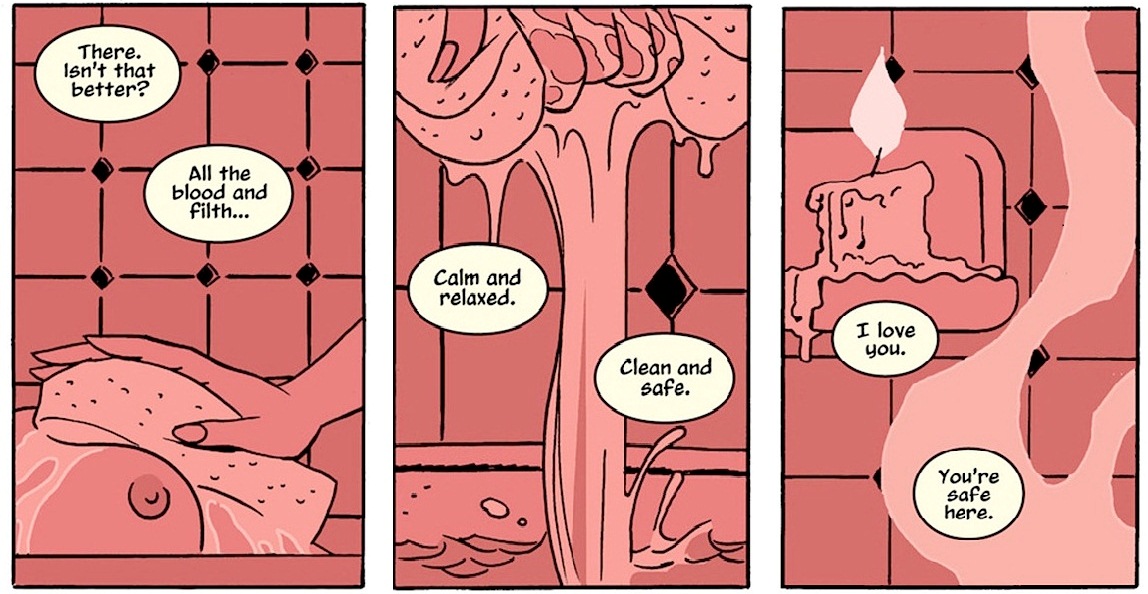

Ursula appeals to a statue of Christ to “love [her]”, and Christ answers her call by sending her an “angel” in the person of Hollis. The writing is mawkish to the point of being embarrassing: “He picked me up and bore my burden, and he told me to be still. He told me he loved me”. If the spectacle of a knight in shining armour rescuing a damsel in distress isn’t clichéd enough, Cooke’s decision to punctuate the sequence with soft-porn images of Ursula being bathed by her lover Gretchen (Figure A8) makes clear his strategy of treating lesbianism as a delectable spectacle for straight men.

Just as lesbianism is treated as a straight romantic fetish, so male homosexuality is treated as an object of abomination. Bizarrely, Cooke appears to think that romanticizing lesbianism has earned him a license to gay bash with impunity. While Moore’s Nelson Gardner/Captain Metropolis and Hooded Justice were hardly paragons of virtue,[vii] nothing in Watchmen prepares one for the hatchet job done on them in Minutemen. Cooke has rehashed almost every negative gay stereotype in his jaundiced revision of these characters. Nelson is a nincompoop, a publicity whore, a drama queen, a pillow biter; Hooded Justice is a sadist, a murderer, a rapist, a suspected serial paedophile. Cooke has no interest in exploring or understanding these men’s history, relationship and psychology. Instead, every book puts forward sensational scenarios to consolidate their corruption, hypocrisy and monstrosity:

- In Book 1, Nelson and Hooded Justice mastermind a mission that leads to the wrongful burning of a firecracker factory. They shamelessly present their mistakes to the public as a successful intervention of a firearm smuggling operation.

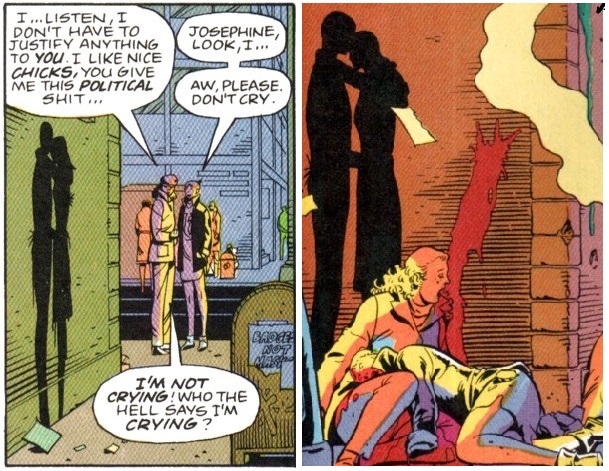

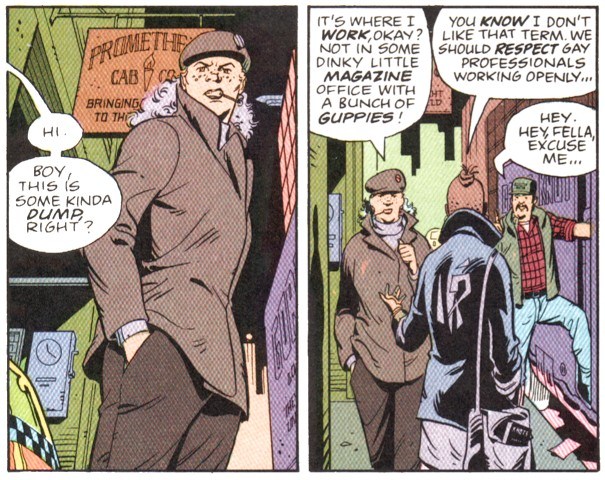

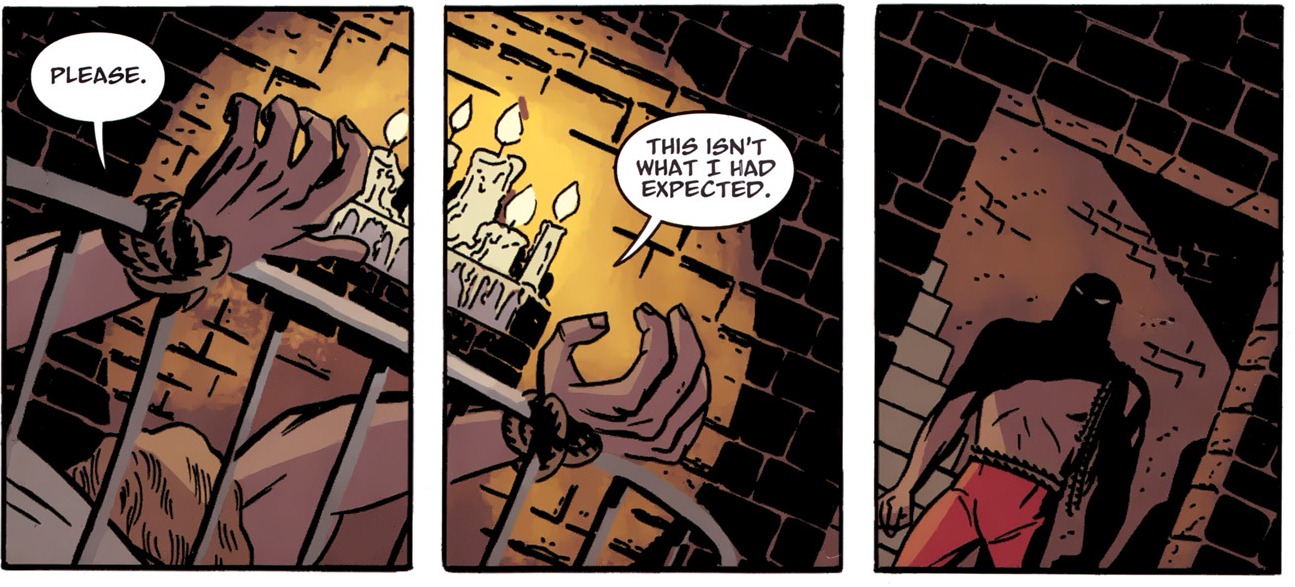

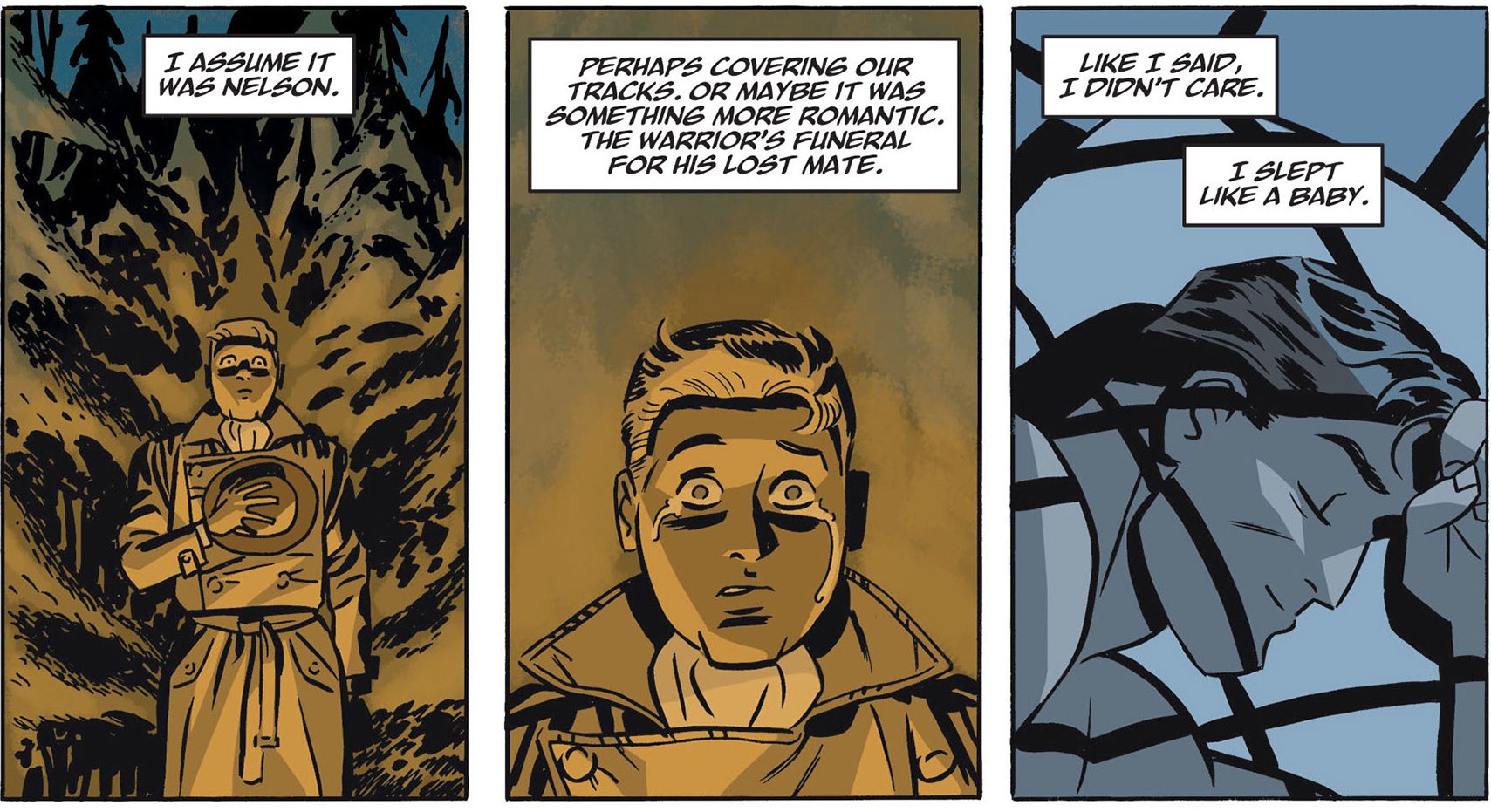

- In Book 2, Nelson is tied up and raped by Hooded Justice (Figure A9). This sinister sequence is intercut with Hollis’ and Ursula’s investigation of a circus where children are known to go missing, which establishes an explicit link between sadism, male homosexuality and paedophilia.

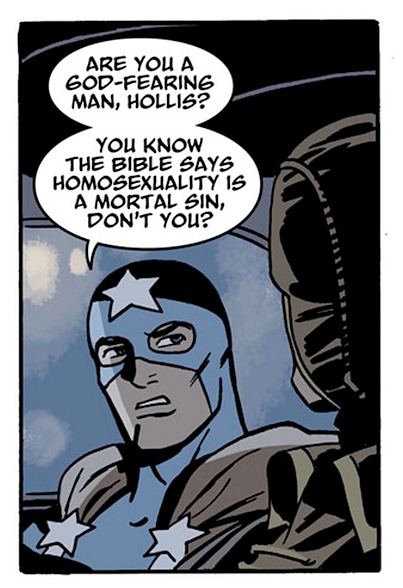

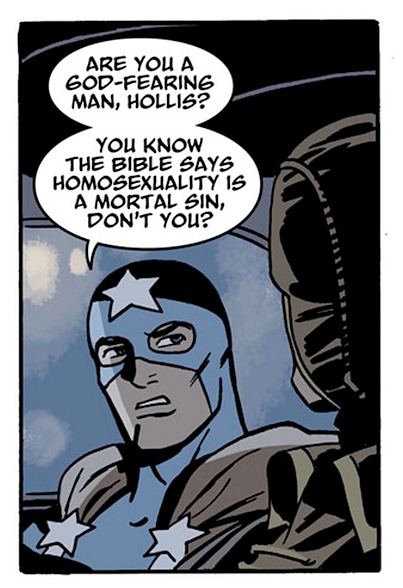

- In Book 3, Nelson sends his new toy boy lover to intimidate Hollis into dropping his plans to publish Under the Hood. Cooke legitimizes the straight male disgust at homosexuality by gratuitously turning Dollar Bill into a spokesman for homophobia (Figure A10). Bill tells Hollis: “I’ll be listening to Metropolis, and I’ll suddenly be thinking about him and Justice and it makes me kind of sick to my stomach”—an attitude Cooke pointedly refrains from disavowing or ironizing.[viii]

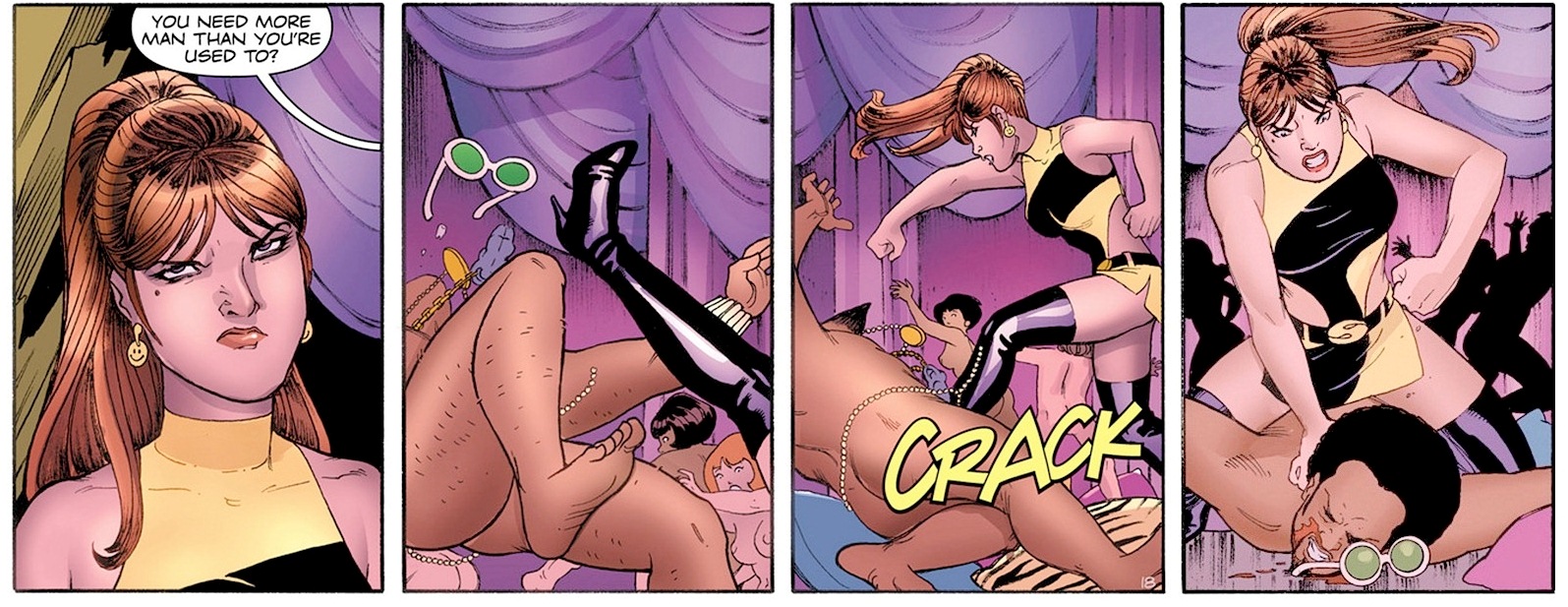

- In Book 4, Nelson and Hooded Justice hypocritically expel Ursula from the Minutemen, and go hustling in “boy’s town” rather than bringing Ursula’s killer to justice. It takes Sally in her kick-ass mode to hunt down and take out the killer. Sally is disgusted by the gay men and tells them contemptuously: “You two should be doubly ashamed. You call yourselves men? Clean up this mess. It’s all you’re good for.”

- In Book 5, Nelson and Hooded Justice lead a heroic duo Bluecoat and Scout to their deaths in a mission to foil a Japanese terrorist plot to launch a nuclear attack from the Statute of Liberty. Bluecoat and Scout are revealed to be a father and son team, and their selfless heroism contrasts sharply with the corrupt egotism of the gay duo.[ix]

- In Book 6, Nelson wallows in self-pity and betrays Hooded Justice by revealing his hideout to Hollis. After Hollis hunts down and kills Justice, Nelson “screech[es]” like a drama queen and blows up his compound ala Edgar Allan Poe’s “Fall of the House of Usher” (Figure A11) while Hollis helps his injured “best friend” Byron/Mothman away.[x] The insinuation is that Nelson is a self-pitying degenerate destined to spend the rest of his life alone, whereas Hollis can look forward to being a surrogate father to Sally’s daughter and a mentor to the neighbourhood’s kids.

Reversing Watchmen’s subversion of conventional morality and sexual stereotypes, Cooke has reconstructed a good-versus-bad dichotomy in which a fetishized lipstick lesbian represents “good”, two despicable gay men represent “bad”, and a noble straight man represents “normal”. In this way, he has undone much of Moore’s and Gibbons’ progressive depiction of sexual minorities and replaced it with some banal heterosexist clichés.

Reconstruction 2: Macho Antihero and Legitimate Rape

Another revolutionary aspect of the original Watchmen was its deconstruction of the genre’s valorization of aggressive masculinity. Some examples of this type of “macho antihero” are Conan the Barbarian, the Punisher, Wolverine, Deadpool, and just about any male protagonist from a Frank Miller comic. The heroic power fantasy projected by this macho antihero stereotype explicitly pampers the male readers’ ego, so it follows that one of the macho antihero’s essential attributes is his sexual aggression towards women. In the course of the macho antihero’s adventure, he is expected to bed many women and break many female hearts; he is just too much of a stud to tie himself down to one woman.

Even such fantasy tends, however, to draw a line between sexual aggression and actual rape. While the macho antihero’s code of honor usually allows him to rough-handle women (e.g. pinching their butts; shoving them aside in battles; knocking them out “for their own good”), very rarely would the macho antihero be depicted as a rapist: a role reserved for villains.[xi] The underlying assumption is that the macho antihero doesn’t need to rape; he can work his way up the skirt of any attractive female who isn’t already throwing herself at him. Besides being sexually endowed, the macho antihero is a rough diamond, an action man, a warrior, a truth-speaker and a follower of his own inexorable code of macho honor.

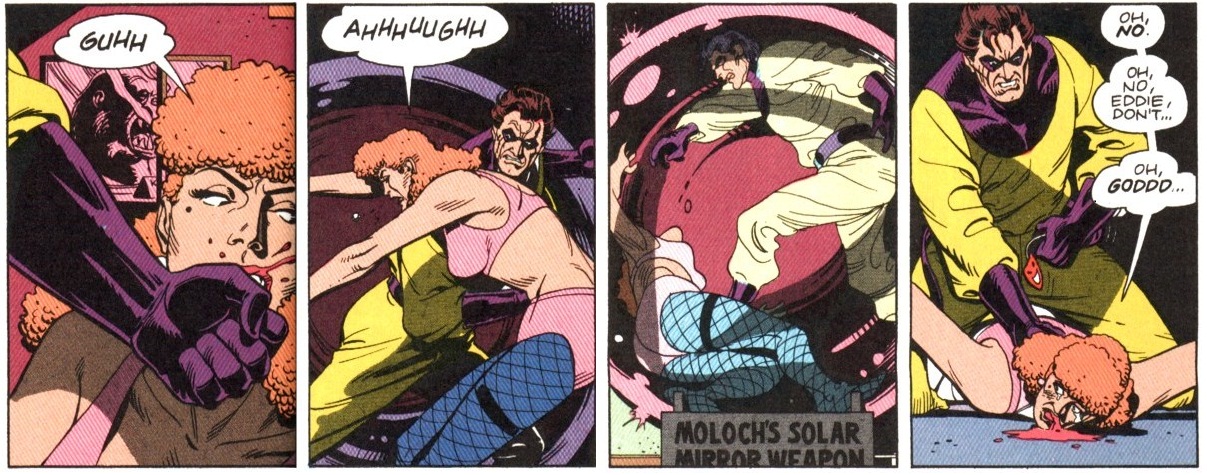

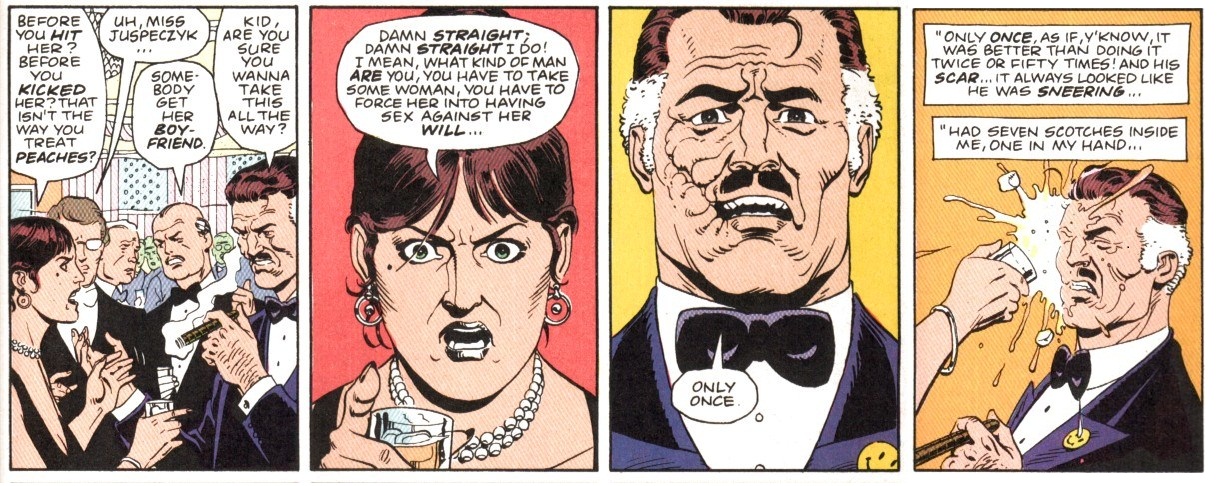

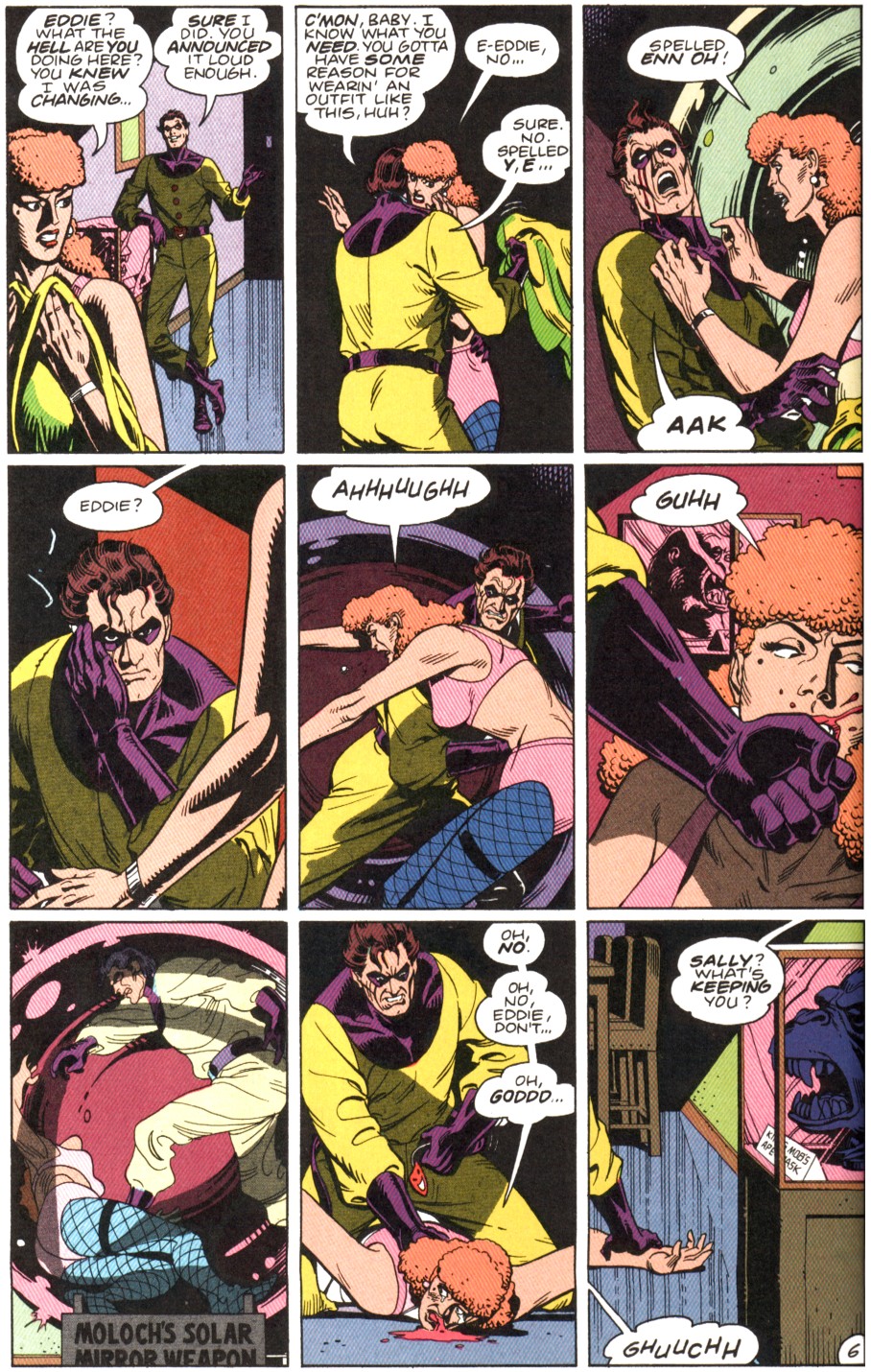

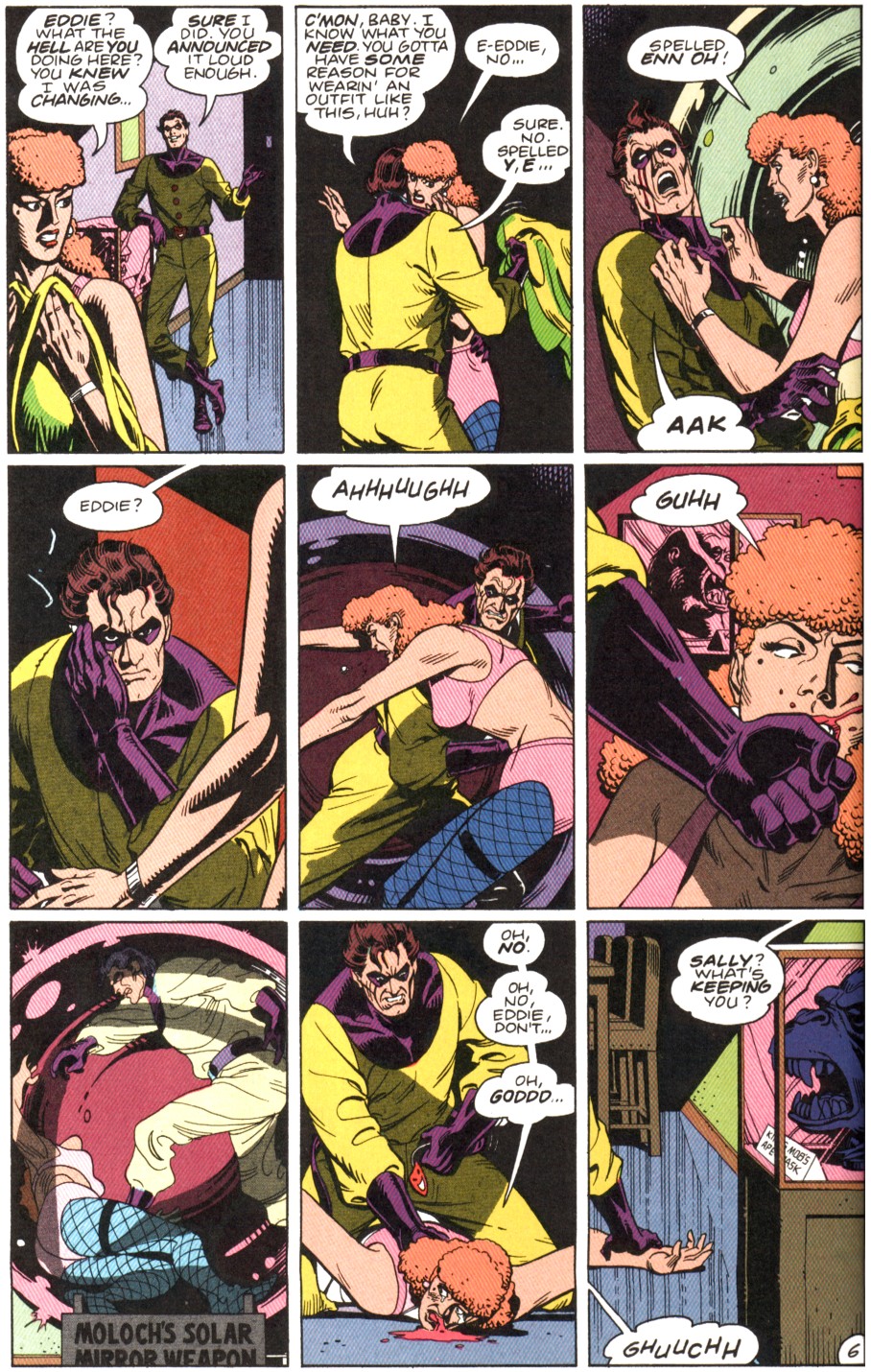

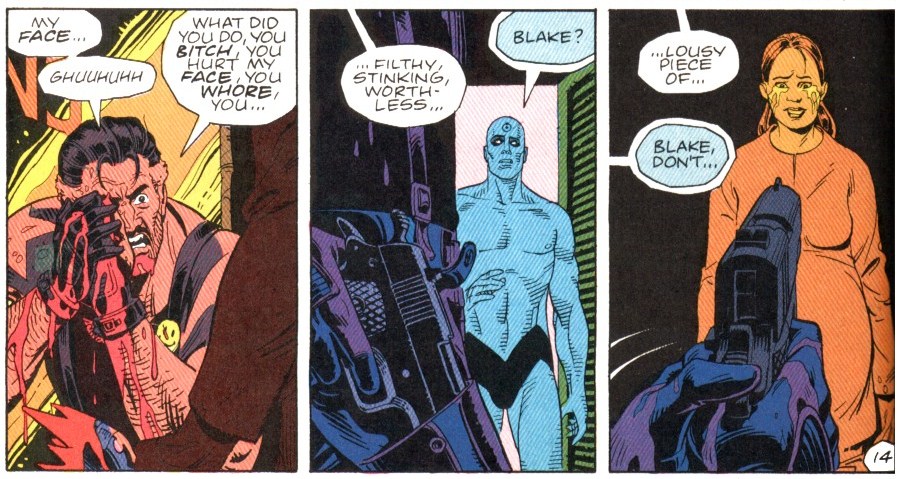

In Watchmen, Moore and Gibbons created Eddie Blake in order to completely demolish this stereotype. He is their nightmarish version of a macho antihero turned brutal misogynist/homicidal maniac. The cigar and machine gun associated with him are obvious phallic symbols, yet his phallus is emphatically used to hurt, intimidate and destroy. Moore and Gibbons went out of their way to show Eddie’s brutal misogyny in two overtly confronting scenes: the attempted rape of Sally, and the murder of a pregnant Vietnamese girl. The story is complicated by the fact that, some years later, Sally has a one-night stand with Eddie, which results in the birth of Laurie. However, this development isn’t meant to exonerate Eddie. In Sally, Moore broke new ground by using superhero comics as a medium to explore the psychology of an abused woman.[xii] For this exploration to have any credibility or substance, the following points are crucial:

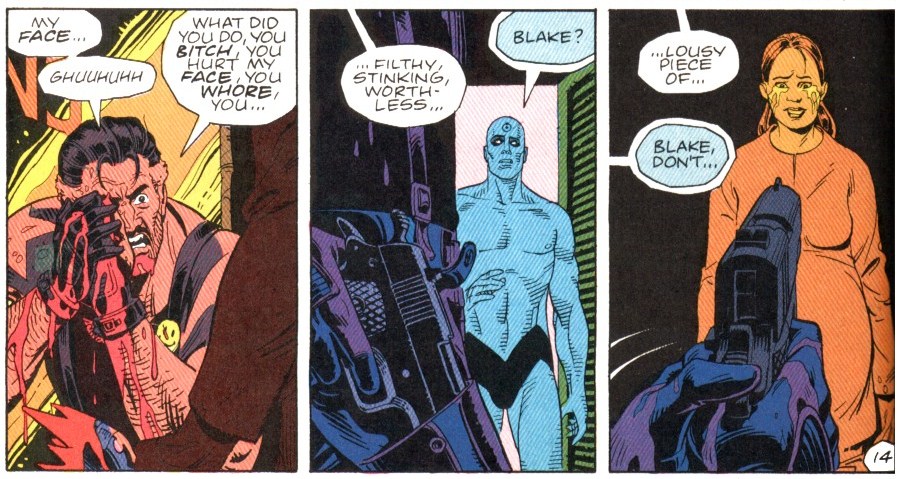

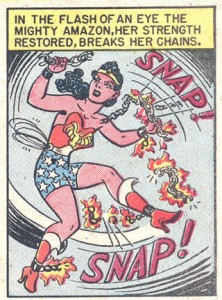

- Eddie tries to rape Sally, and the act is brutal (Figure B1). She clearly says “no”, but he still tries to rape her. As drawn by Gibbons, the violence is unflinching. We see the fear in Sally’s eyes and the blood in her mouth as Eddie punches her face and kicks her gut. Hollis describes being haunted by the memory of “bruises along [her] ribcage” (II.32). Laurie is outraged at Rorschach’s suggestion that the “alleged” rape is a “moral lapse”: “You know he broke her ribs? You know he almost choked her?” (I.21)

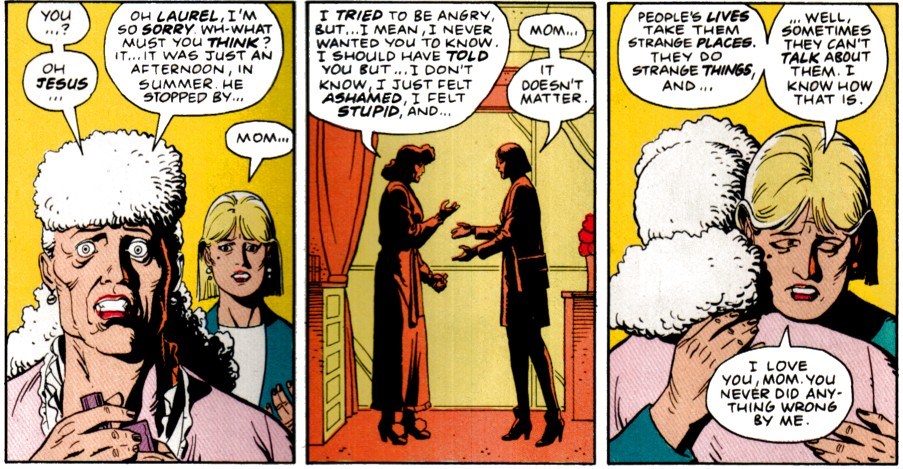

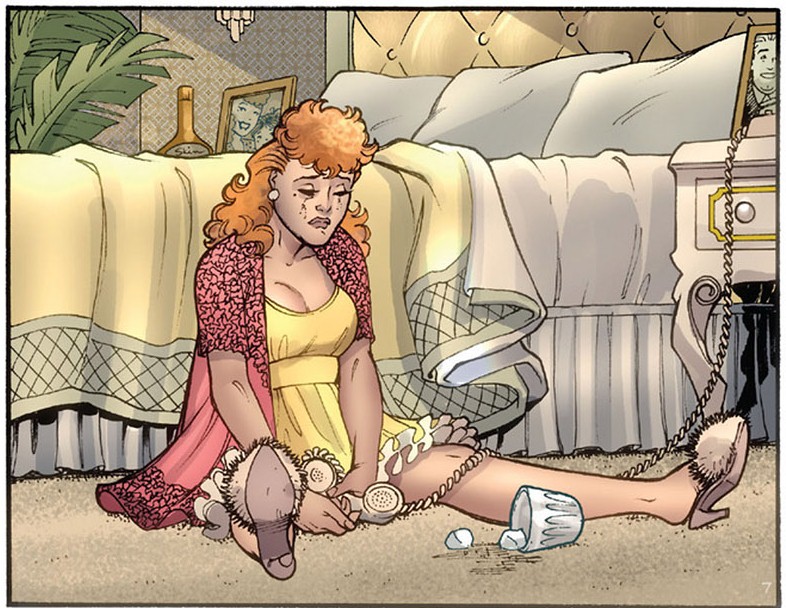

- Some years later, Sally sleeps with Eddie and becomes pregnant with Laurie. This episode happens off-stage. Her motivation isn’t spelt out, but in her own words: Larry was “[never] there”; she tried to be angry with Eddie but “couldn’t sustain the anger”; and he was “gentle” and “gentleness [in a guy like that] … means you reached some of that magical romance and bullshit that they promise you when you’re a kid” (IX.7).

- Their one-night-stand (“it was just an afternoon, in summer. He stopped by” [XII.29]) fills Sally with shame, confusion and self-hatred for the rest of her life. She hides the truth from Laurie because she is afraid that if Laurie finds out, she would resent and despise her.

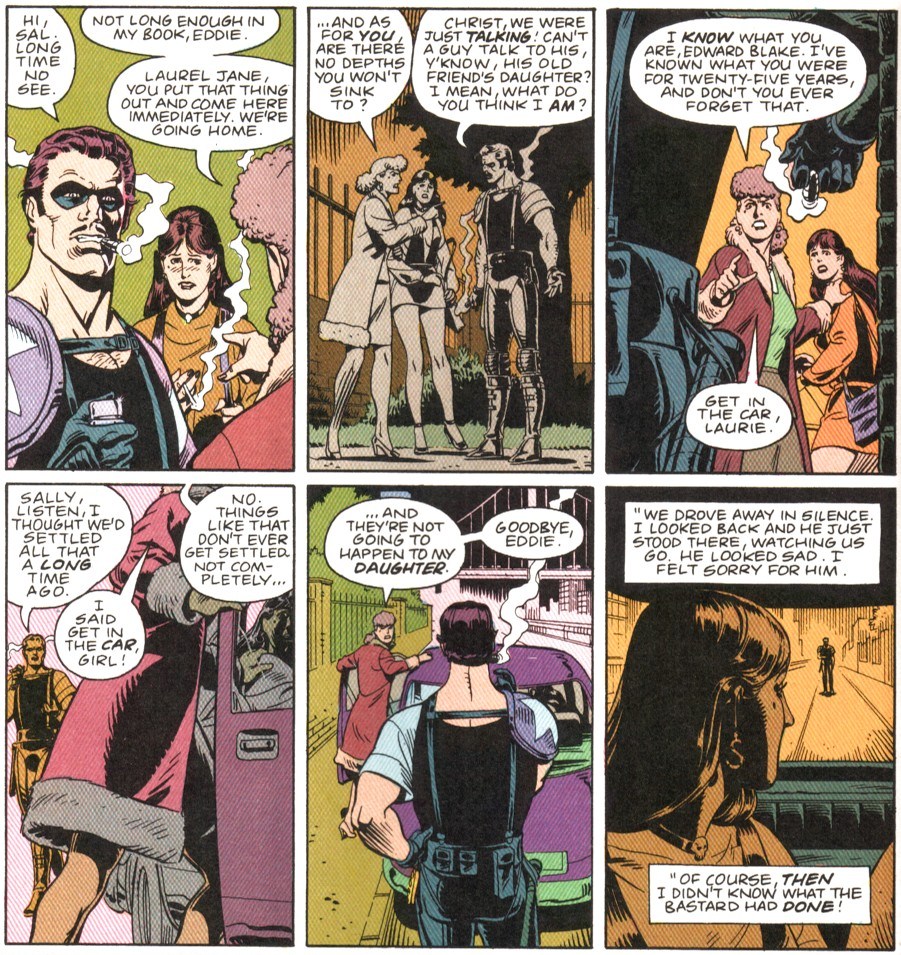

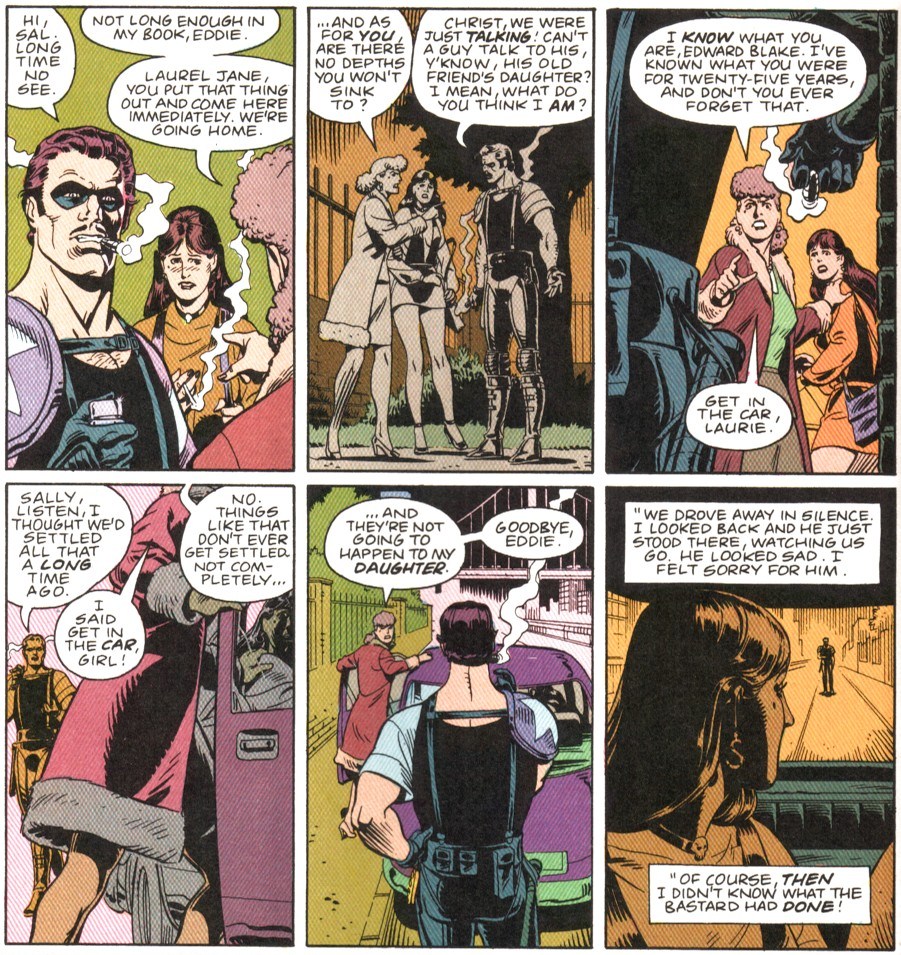

- Despite Sally’s feelings for Eddie, she wouldn’t let him anywhere near Laurie, believing he is the kind of man capable of molesting his own daughter: “I know what you are, Edward Blake. I’ve know what you were for twenty-five years, and don’t you forget that.” (Figure B2)

In short, Moore and Gibbons de-romanticized the macho antihero stereotype by insisting on the actuality and consequences of Eddie’s violence, especially the physical, emotional and psychological damages he inflicted on Sally. This doesn’t mean that they made Eddie completely unsympathetic; they just didn’t make him sympathetic on account of his aggressive masculinity. There is poignancy about a man so conscious of his guilt that he couldn’t even bring himself to confess to a priest and has to pour his heart out instead to a petty ex-criminal: “I did bad things to women. I shot kids in ‘Nam!” (II.23) There is also a touch of poetic justice to the idea that a violent misogynist should find himself yearning for the love and respect of a strong-minded daughter at the end of his life. Yet, while the book makes an effort to humanize Eddie, the last thing it offers is the luxury to admire and celebrate his aggressive masculinity.

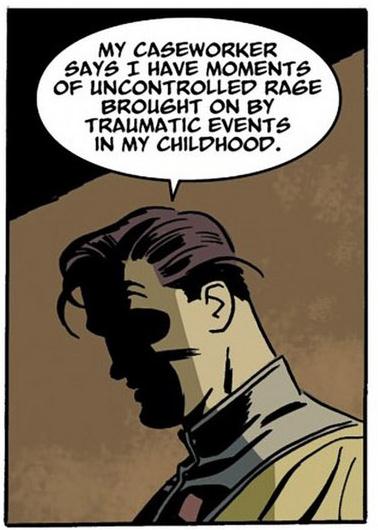

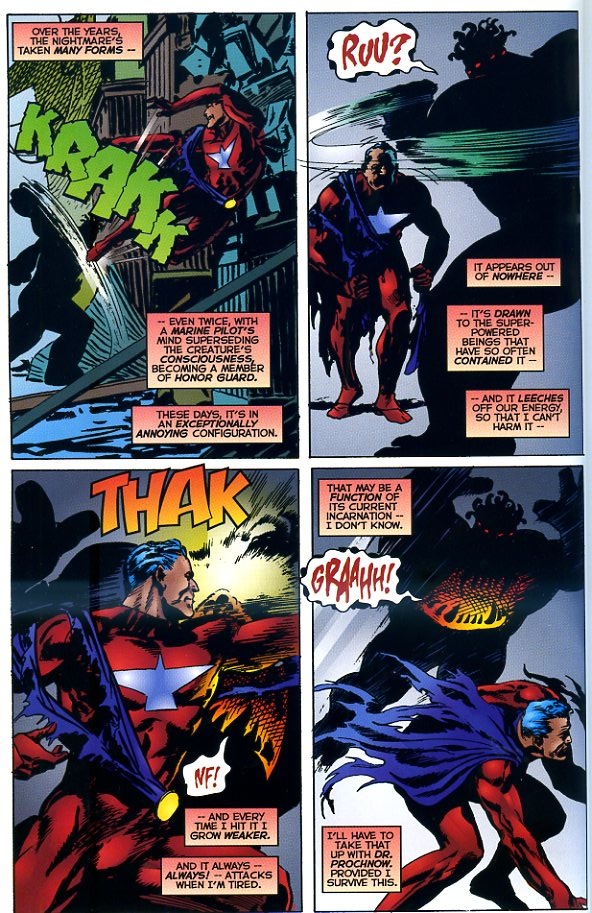

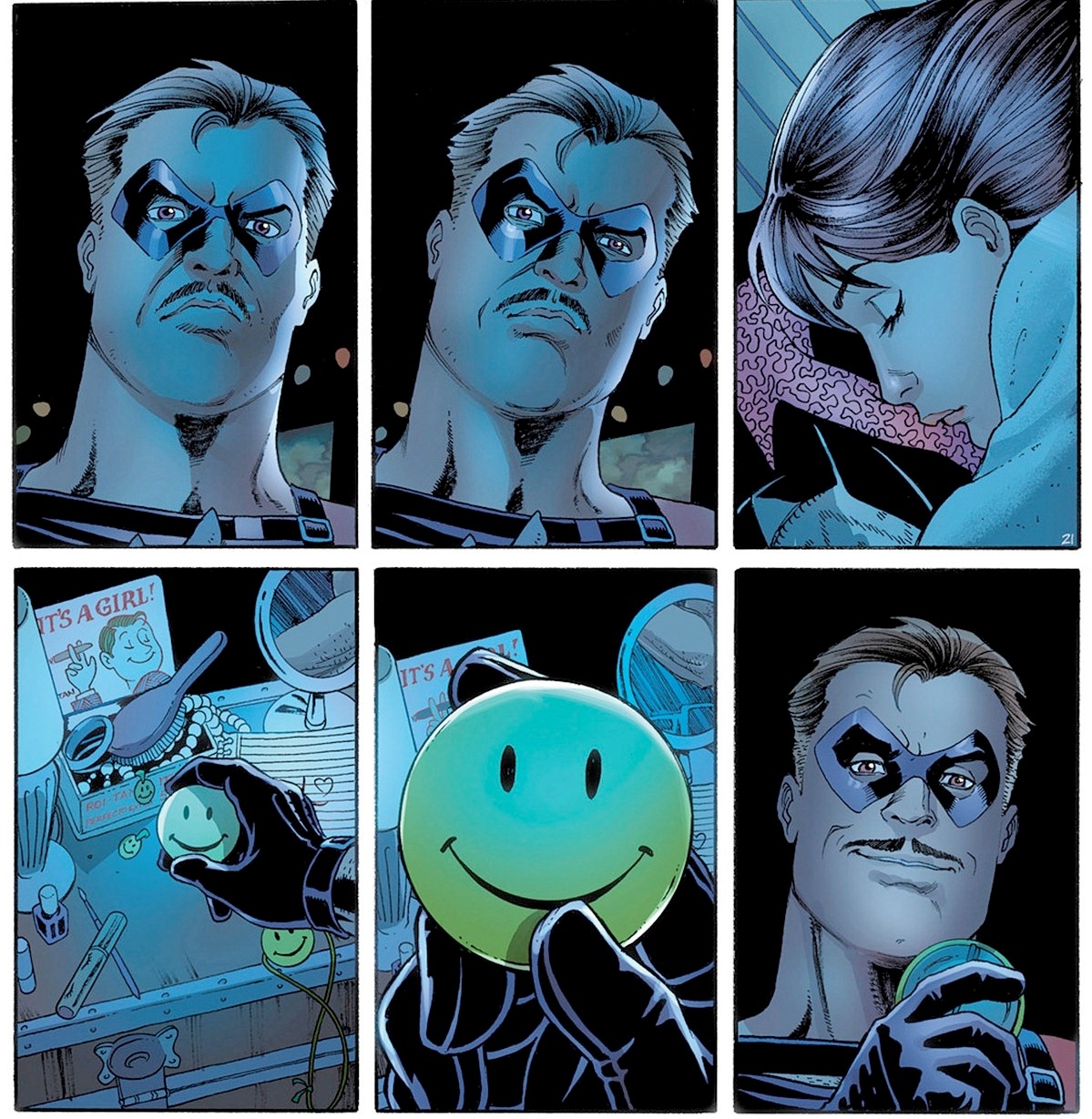

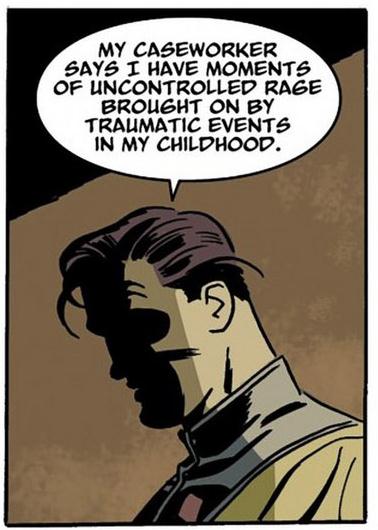

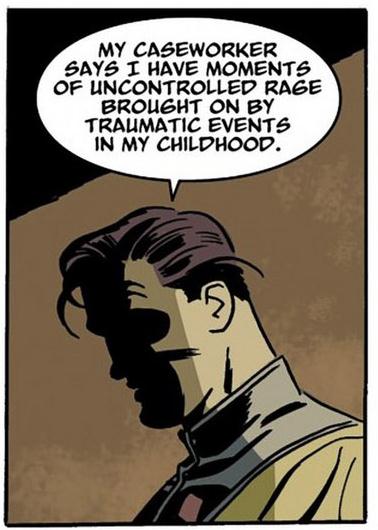

In Minutemen, Cooke throws all this out of the window and sets out to retcon Eddie into a conventional macho antihero.[xiii] Interestingly, the whitewashing of Eddie comes in tandem with the blackening of Nelson and Hooded Justice. This is noticeable already in Book 1’s introductory vignettes. Even when Eddie is about to beat someone senseless with a stick, Cooke ensures that maximum sympathy is marshalled for him by putting in his mouth an out-of-character confession that he experiences “moments of uncontrolled rage brought on by traumatic events in my childhood” (Figure B3). In contrast, the vignettes about Hooded Justice and Nelson are limited to revealing the grotesque sadism of the former (killing a man even after he has dropped to his knees begging for mercy) and the pompous vanity of the latter (taking a bath in his penthouse and bossing a manservant around).

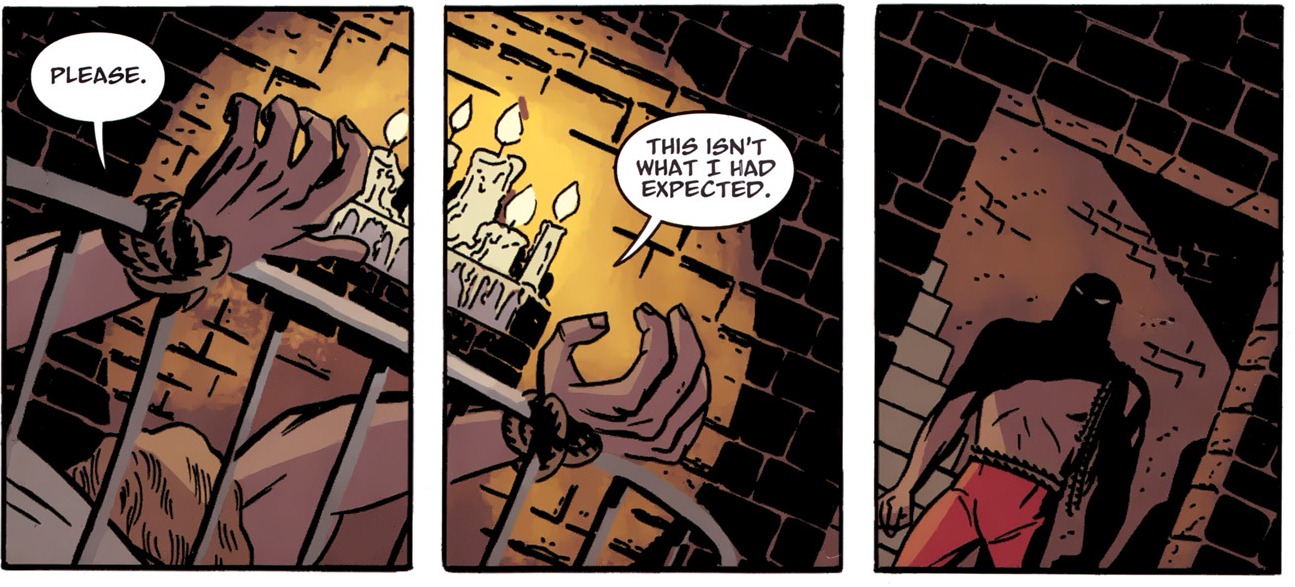

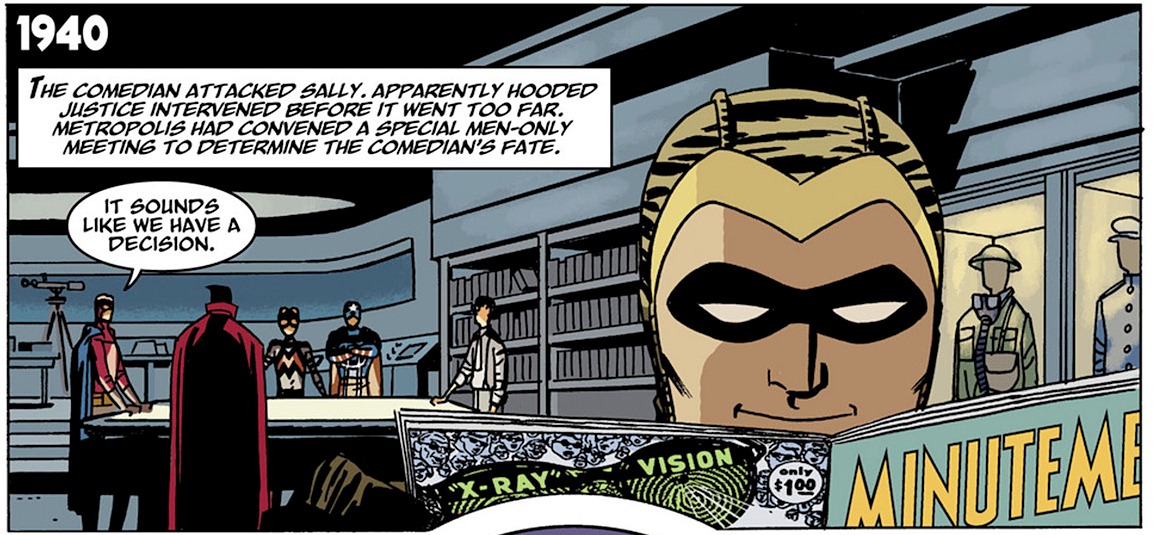

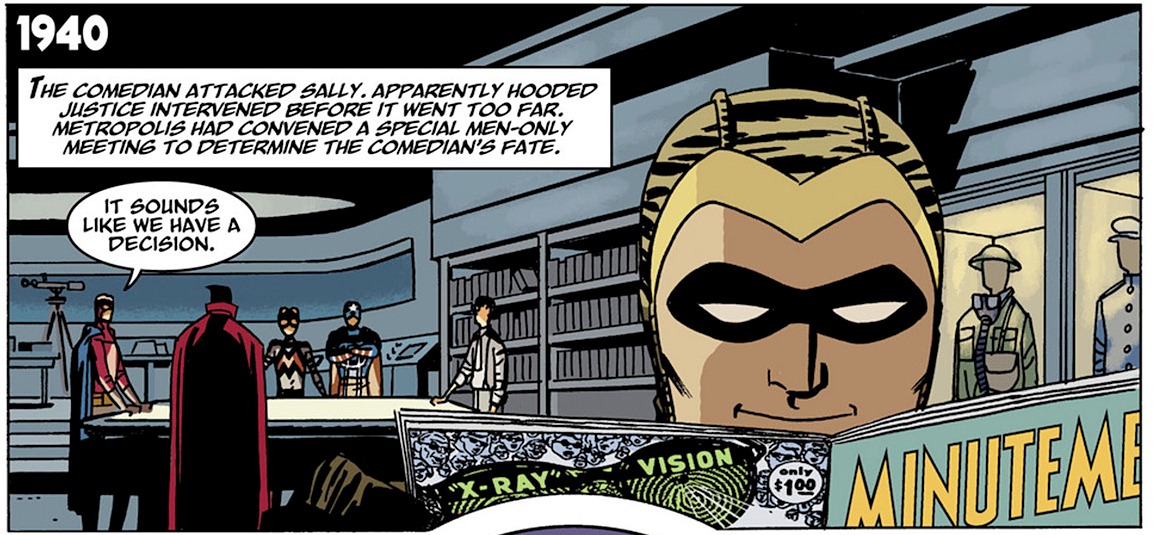

The introductory vignettes seem a minor quibble compared to what Cooke does next to exonerate Eddie: retelling the attempted rape of Sally to call into question whether it was an attempted rape. Cooke employs a number of strategies to this ends. First, he writes the victim out of the picture: no image of Sally is shown immediately before, during or after the attempted rape. In the absence of any image showing Sally’s bloody mouth, bruised body, broken ribs, or a scene showing her recuperating in hospital, the incident becomes mere hearsay, a product of Hooded Justice’s biased perception and Nelson’s prissy overreaction. Second, Cooke prefaces the Minutemen’s emergency meeting by a light-hearted image of Hollis reading a comic book (Figure B4).

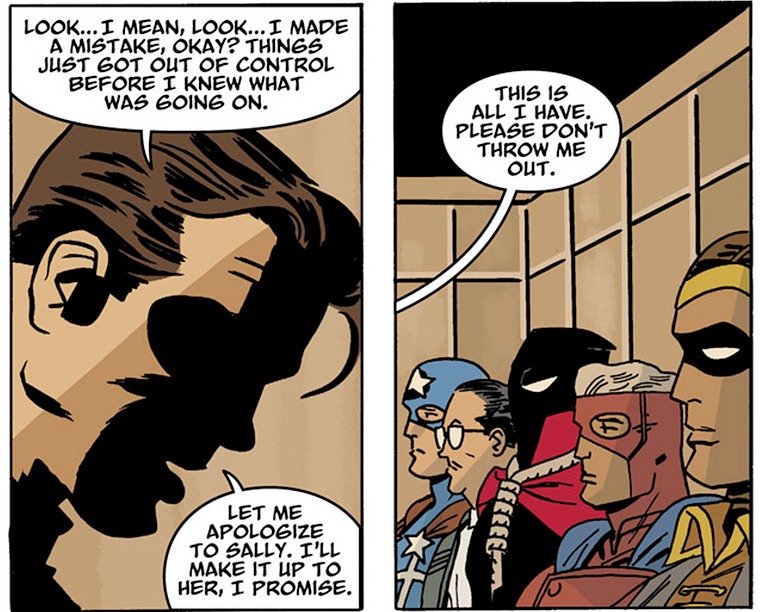

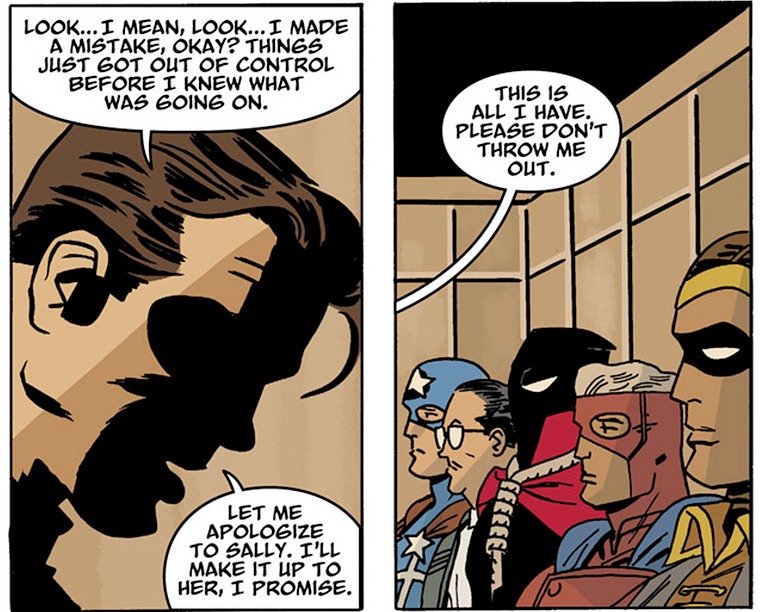

This alters the tone of the incident and supports Eddie’s claim that he is being trialled by a “kangaroo court”. Whereas Moore repeatedly called the incident “rape”, Cooke plays legal semantics with words such as “apparently” and “attacked” (at common law, Sally’s apprehension of danger is enough to make it an “assault”). Third, Eddie is no longer the cocky, unrepentant scoundrel who taunted Hooded Justice even after committing a serious crime. Instead, he is a vulnerable, confused, contrite “kid” who pleads his case poignantly with his peers: “Let me apologize to Sally. I’ll make it up to her, I promise. This is all I have. Please don’t throw me out” (Figure B5).

By omitting any visual evidence of Sally’s injury, Cooke gives weight to the theory that what happened is as Eddie says: a harmless miscommunication between him and Sally. So the emphatic “ENN OH” that Sally tells Eddie is now re-spelt “maybe”, and rape is something that a rapist can just “make up” to the victim with an apology.

The retconning goes further. When Eddie’s peers refuse to forgive him, Cooke turns the scene around to allow Eddie to become judge and jury of his peers (Figure B6).

The incident set up by Cooke in Book 1 to establish Nelson’s and Hooded Justice’s corruption now allows Eddie to turn the tables on his accusers: “We blew up a goddamn warehouse full of firecrackers and we told the world we’d saved them from Axis terrorists.” Eddie’s righteous indignation is also explicitly sexuality-based: he sees heterosexual rape as no worse than homosexuality: “You want to talk about perverts? You sick fucks are going to judge me?” Then, Cooke reverses Moore’s and Gibbons’ humiliating spectacle of Eddie being caught with his pants down by showing Eddie skilfully defeat Hooded Justice in a scuffle. While holding down Hooded, Eddie reiterates his righteous contempt for the disgusting gay men: “Stop squirming, you pansy”; “Stop right there, missy. I’ll choke your boyfriend to death”. And with a stinging anti-gay taunt: “Bunch of fags. Go fuck yourself”, Eddie exits the scene with his gun cocked and his head held high. In contrast, Nelson is left embarrassed and exposed, the panel cutting off half his face as his metaphorical hair pins fall out. In light of this, the supposedly ironic propaganda cartoon that completes the sequence—“What a man!”—can be read literally as a valorization of Eddie’s gutsy exposure of his teammates’ hypocrisy.

Cooke further consolidates the theory that the rape is “legitimate” in his depiction of Eddie’s reunion with Sally in Book 4. In the original Watchmen, Sally describes their reunion like this: “I shouted at him. He looked surprised, couldn’t image why I’d bear a grudge …. I just couldn’t sustain it, the anger” (IX.7). This suggests among other things that Eddie is a man so morally deficient that he felt no qualms about casually dropping by to woo a woman he has bashed and tried to rape. Instead, Cooke whitewashes their reunion by placing them in a completely honorable setting: at the graveside of the martyred Ursula. Dressed in a nice clean suit to pay his respects to his fallen comrade (those “bunch of fags” Nelson and Hooded are the only ones who didn’t show up), Eddie indeed “ma[kes] it up” to Sally. He taps her gently on the shoulder. She, not he, looks “surprised”. There is no shouting, no attempt to sustain her anger, and her uneasiness is easily quelled by his manly reassurance of his good will. Cooke then treats us to an extended flashback to Eddie’s participation in the Pacific War, which becomes a retcon version of the later Eddie in Vietnam.

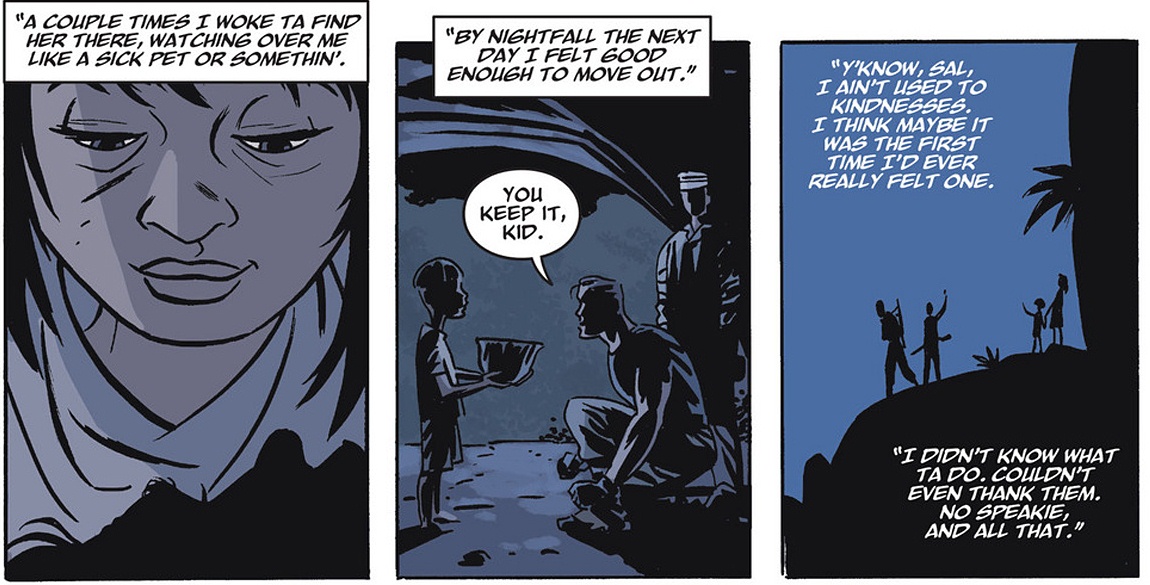

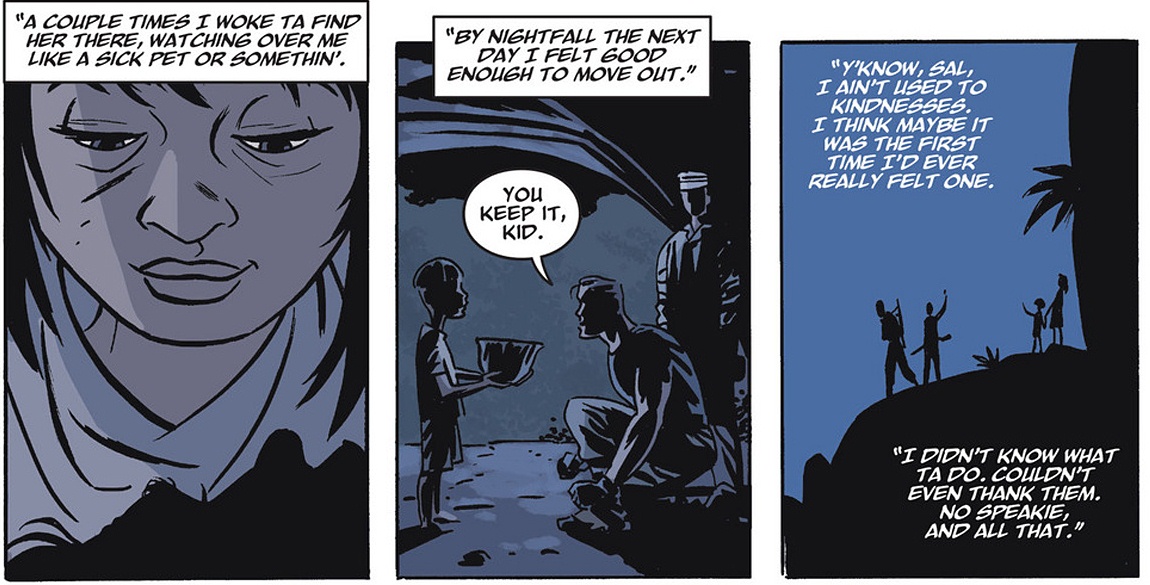

In contrast to Moore’s hyper-masculine psychopath who found his true element in the killing fields of wars, Cooke’s Eddie is portrayed as an innocent soldier poignantly losing his innocence in a contrived scenario worthy of any military tearjerkers. Injured on the battlefield, Eddie was rescued by a kind-hearted Solomon woman and her little boy (Figure B7).

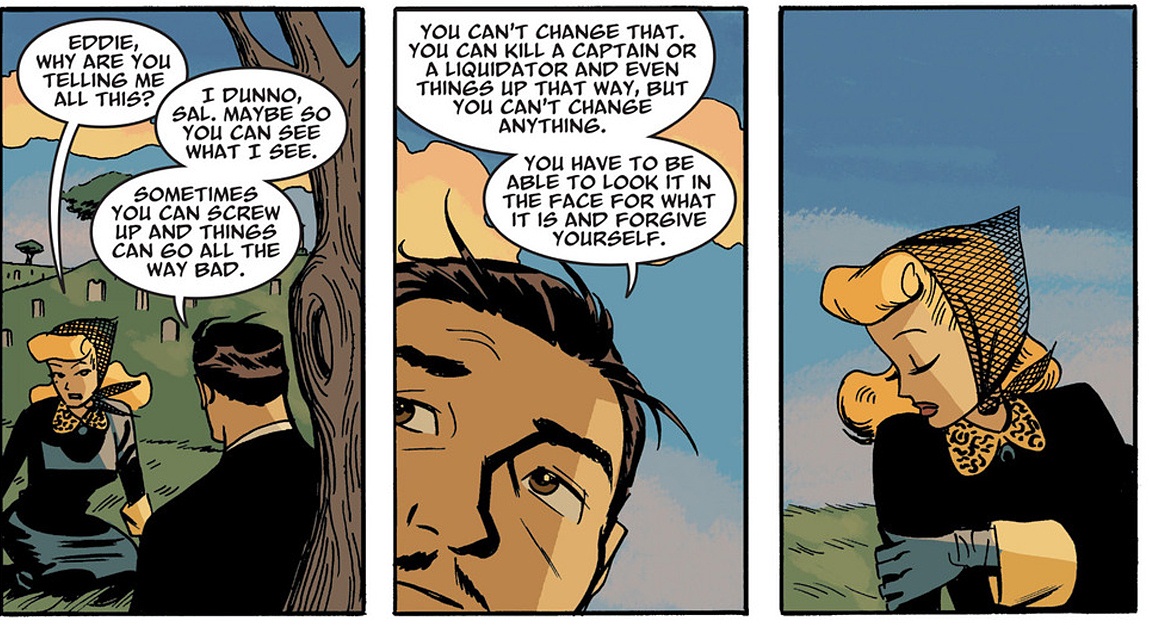

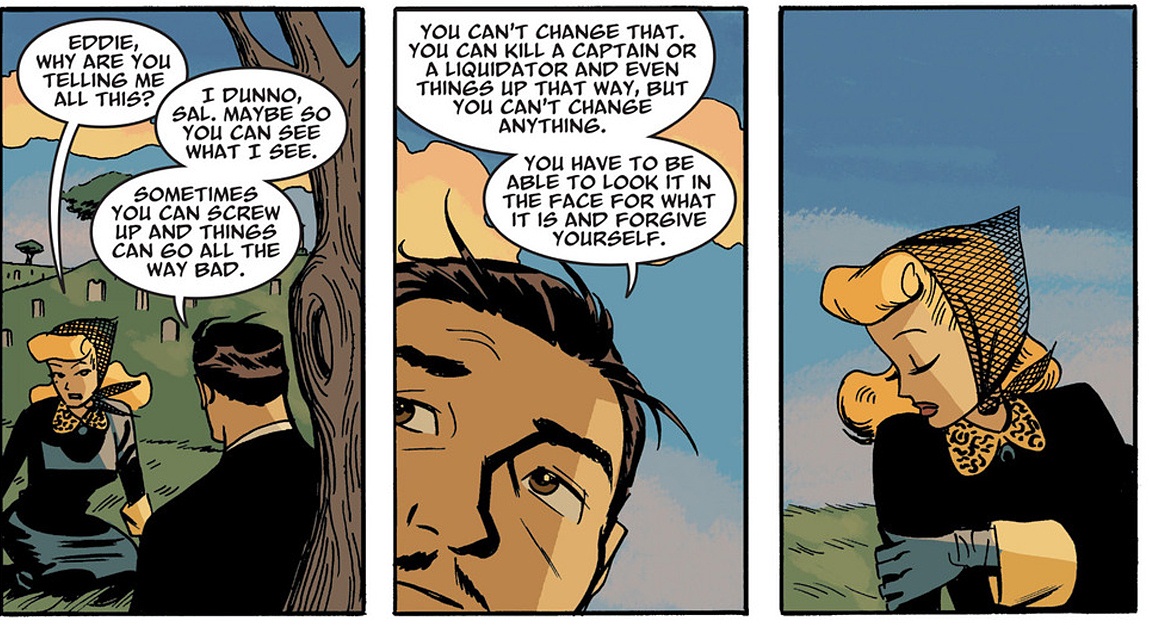

Despite their cultural and linguistic differences, he bonded with the pair because this was the first time anyone had treated him with kindness. He was devastated when his nasty commander gave orders to bomb the natives’ village and he could do nothing to save their lives. So, Eddie once again learned that life is a bitch and one must play hard to survive: he killed the nasty commander that killed the woman and boy. Apparently, the war also brought out something of the poet-philosopher in the uncouth Eddie, and he teaches Sal a lesson from the school of hard-knocks: “You have to be able to look it in the face for what it is and forgive yourself.” (Figure B8)

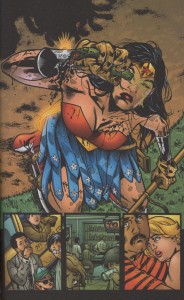

Sally reacts by looking away demurely like a little girl, acknowledging the potency of Eddie’s manly eloquence. So Moore’s and Gibbons’ morally bankrupt aggressor has morphed into a salt-of-the-earth gentle giant spouting pearls of wisdom to purify a woman’s soul. Presumably, the shooting of the pregnant Vietnamese woman thing (Figure B9) is just an isolated incident that happens along with all the other shits that happen by the time Eddie gets to ‘Nam.

And because Eddie is such a rough diamond, macho badass and poet-philosopher, Sally naturally falls in love with him and offers him her body and soul. Their reunion is no longer “just an afternoon, in summer. He stopped by. I tried to be angry …. I just felt ashamed” (XII.29). It is now retconned into a serious relationship which she wholeheartedly embraces and passionately enjoys. In contrast to Dr Manhattan’s epiphany that Sally “loves a man she has reasons to hate” (IX.26), Cooke’s version of Sally really has no reasons to hate Eddie except that their consensual relationship didn’t work out the way she wanted. So, trauma, anger, shame, guilt and emotional dependency which are the complex symptoms of an abuse victim are reduced to stereotypical female neurosis and jealousy that Eddie is just too much of a stud to settle down with her. And what Moore and Gibbons had the good sense to leave out, Cooke exhibits in full chauvinistic detail: he not only depicts Laurie’s conception as the result of a quick shag between Eddie and Sally in the lavatory on Sally’s wedding day, he also depicts it as a facetious homage to the famous Tijuana bible image in the original Watchmen (Figures B10-11).

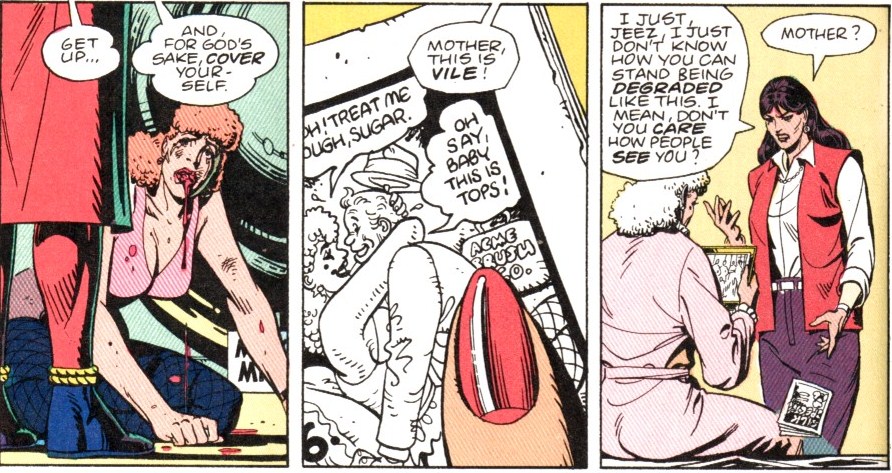

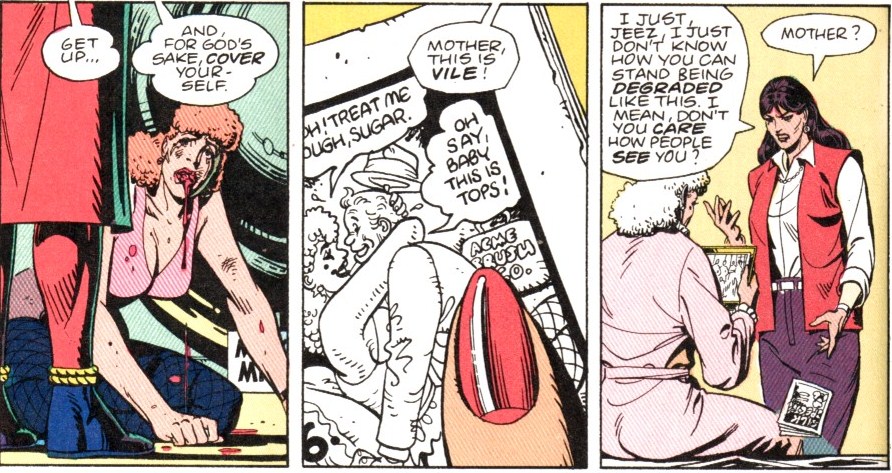

The contrast in concept and execution is stark. In Moore’s and Gibbons’ depiction, the three panel sequence offers an incisive critique of gender violence in comics:

- Panel 1: A confronting image of sexualized violence is presented. Sally is on her hands and knees, spewing blood while exposing her cleavage to the readers. Sally’s “rescuer” Hooded Justice stands over her. He is unsympathetic to her plight and tells her to cover up, insinuating that she is partly to blame for Eddie’s violation of her.

- Panel 2: The scene abruptly changes to a page from a Tijuana bible. The crudely drawn porno cartoon reiterates the misogynistic stereotype that women invite rape and enjoy “rough” sex. But the comic-within-a comic device makes the readers self-conscious that they are reading a comic book, and reminds them of the genre’s tendency to eroticize sexual violence. Covering the most explicit part of the porno cartoon and frustrating the (male) readers’ gaze is a woman’s red-varnished fingernail and the libido-dampening caption: “Mother, this is vile!”

- Panel 3: The image zooms out and we see that the speaker is Laurie, who tosses the porno comic aside in disgust and scolds Sally for accepting this kind of degrading treatment of women. The comic book tradition of eroticizing sexual violence is undercut by a woman’s angry, accusatory voice.

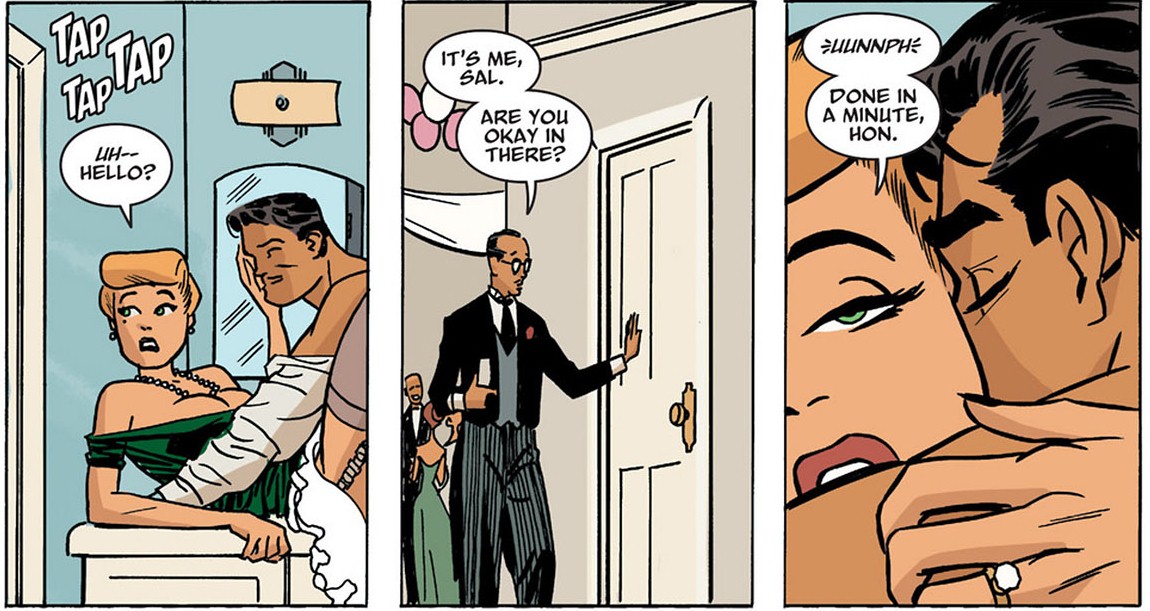

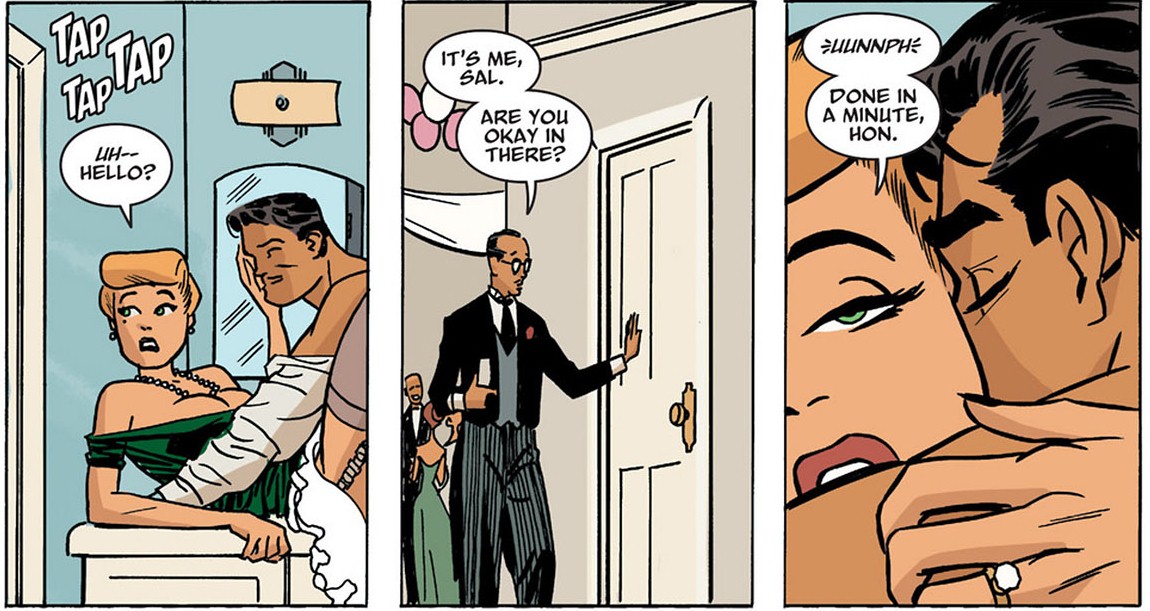

In Cooke’s depiction, the three panel sequence is all about celebrating male sexual conquests and boosting male ego, and would not be out of place in any seedy frat boy sex comedy:

- Panel 1: A tawdry image of frivolous sex is presented. Eddie is seen screwing Sally in the lavatory. Good old Eddie has finally vindicated his manhood by knocking up the girl who thought she could say “no” to him.

- Panel 2: Larry Schexnayder, the bumbling beta male, anxiously asks his bride why she is taking so long. He is stupidly imperceptive that he has been cuckolded by a real man.

- Panel 3: The image zooms in on Sally’s face. With a dazed expression, she fobs off Larry while enjoying being banged by Eddie. Significantly, the readers’ perspective corresponds to Eddie’s: they are positioned as Eddie giving it to Sally. Her line “Done in a minute” is sexually suggestive and anticipates the come-shot that happens off panel.

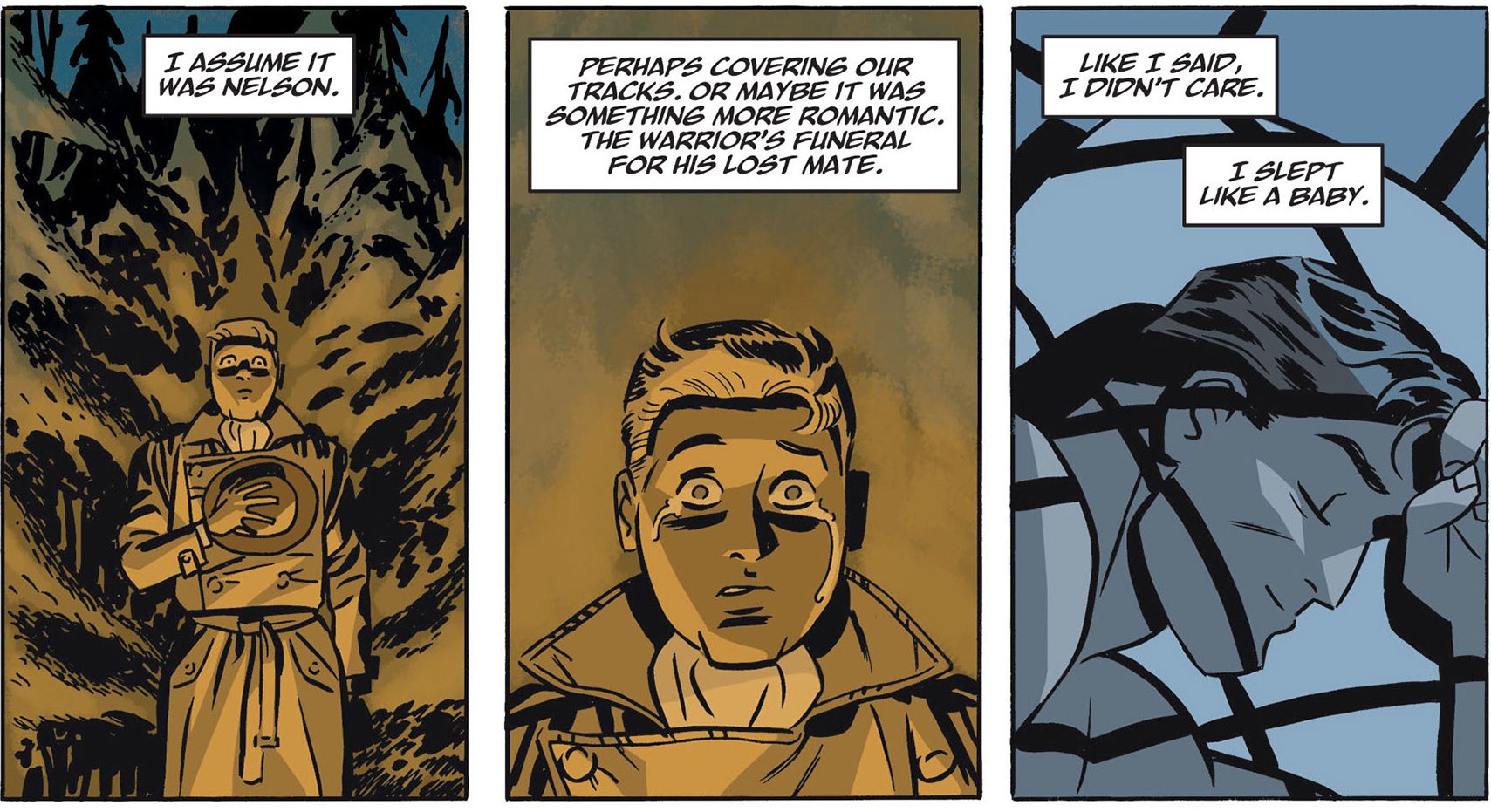

Thus a subtle, incisive critique of sexual violence is transformed into a moment of adolescent toilet humor and phallocentric double entendre in complete support of Eddie’s virility. This more or less summarizes the tenor of all six books of Minutemen. Cooke has ensured that just about anything Eddie does is given an explicit or implicit justification. Even the “twist” in Book 6, if one thinks about it, is really all about setting up a big finish to demonstrate what a cool badass Eddie is. In the original, Eddie’s suspected part in the murder of Hooded Justice was part and parcel of his nasty, vicious personality. Hooded Justice was completely right to interrupt the attempted rape, yet Eddie not only wouldn’t admit that rape is wrong but also wouldn’t allow the perceived blemish to his manhood to go unrevenged. And rather than confronting Hooded upfront, he likely resorted to a secret assassination: a bullet to the head, J.F.K.-style.[xiv]

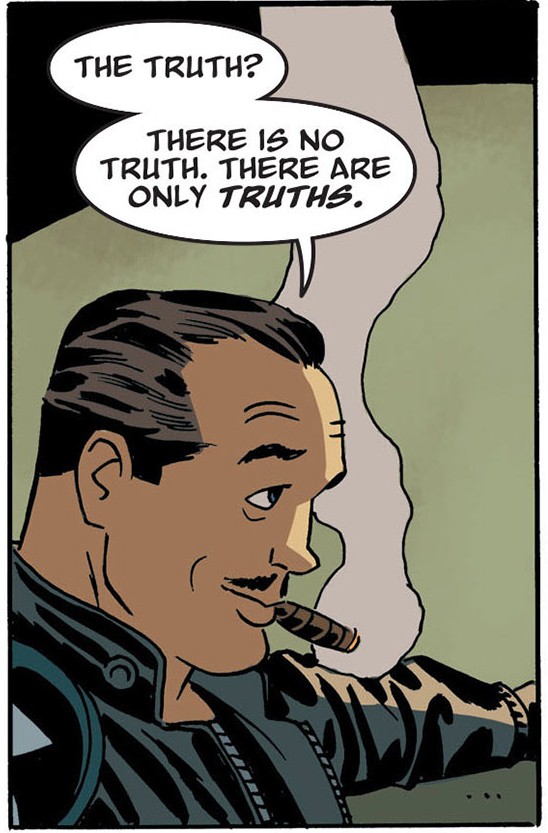

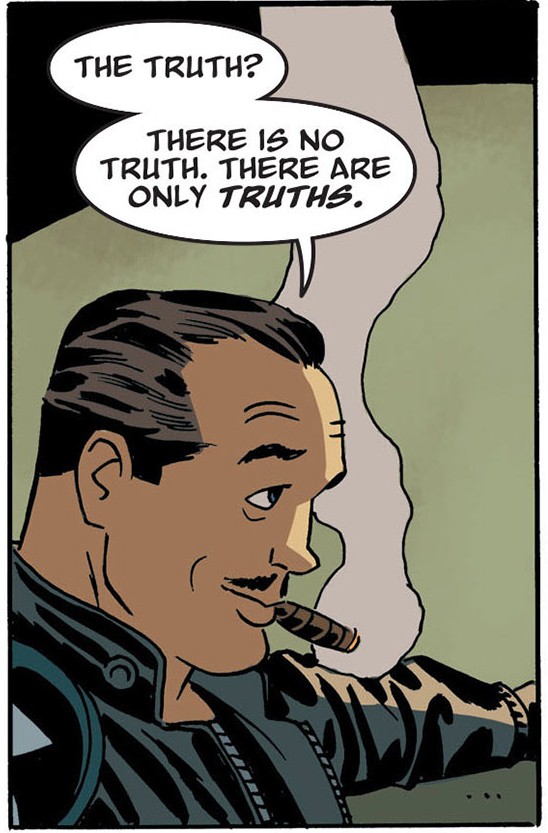

In Cooke’s version, everything comes together to vindicate Eddie. Hooded Justice is a sick bastard who is far sicker than Eddie. Eddie can effortlessly defeat him in head-to-head combat. Eddie’s “attack” on Sally is a harmless misunderstanding rather than a brutal rape attempt. Sally’s reunion with Eddie is a heart-warming romance rather than evidence of her vulnerability, confusion and psychological damage. And Eddie doesn’t even want to kill Hooded—he only wishes to “humiliate” him. The killer turns out to be the unwitting Hollis Mason, who publishes a sanitized version of Under the Hood as a cover to “protect” himself and those dearest to him.[xv] Eddie retains the ability to outsmart and outplay everyone even as his moral culpability is drastically reduced. His sage advice to Hollis: “there are only truths” (Figure B12) becomes the de facto “vision” of the series: it takes a real man to make lesser men see what they don’t want to see.

Eddie is now a macho antihero akin to Frank Miller’s version of Batman, a master tactician who follows his own code of morality and dispenses his own brand of badass justice, a man whose heroism lies in his manly indifference as to whether the world sees him as a hero. Moore and Gibbons’ deconstruction of a macho antihero has been fully reconstructed by Cooke into a traditional macho antihero.

[i] Some critics (e.g. Hughes) have accused Moore of hypocrisy for wanting to stop other people from revisiting Watchmen when so many of his own books are based on other people’s works. While I don’t have any strong objections to the idea of the Watchmen prequels per se, I don’t think the charge of hypocrisy against Moore is really tenable. There is surely a big difference between a writer borrowing elements from public domain classics to create original fictions in a different medium and a large corporation wielding copyright laws to develop a franchise explicitly marketed as being continuous with the most celebrated work of a disenfranchised writer.

[ii] As of 19 May 2013, Minutemen and Silk Spectre are the most favourably reviewed Before Watchmen titles on Comic Book Roundup: Minutemen scores 8.4; Silk Spectre scores 7.9. Scores for the other books are: Dr Manhattan 7.9; Ozymandias 7.0; Rorschach 6.9; Nite Owl 6.1; Moloch 5.7; Comedian 5.4; Dollar Bill 5.3.

[iii] E.g. MTV Geek: [Minutemen] honestly felt like a book I’ll be able to put on my shelf right next to Watchmen. It’s not the original work, but it’s also not, like everyone feared, detracting from Moore and Gibbons’ book… It’s enhancing it” (Zalben); Newsarama: “For the first time since reading the Before Watchmen prequels, I feel like the authors have actually added something to Alan Moore’s seminal work” (Pepose par.1); Superherohype: “Cooke has created back stories that not only don’t negate the original text but make it richer” (Perry, Minutemen par.4); “What [Cooke and Conner] have created is a good story that not only fits well into the Watchmen mythos, but could be removed from the lens of Watchmen and would still hold up” (Perry, Silk Spectre par.2).

[iv] See, e.g. Moore’s interview with Pindling: “I wanted to … make [Rorschach] as like, ‘this is what Batman would be in the real world’. But I have forgotten that actually to a lot of comic fans, ‘smelling’, ‘not having a girlfriend’, these are actually kind of heroic! So Rorschach became the most popular character in Watchmen. I made him to be a bad example. But I have people come up to me in the street and saying: ‘I AM Rorschach. That is MY story’. And I’d be thinking: ‘Yeah, great. Could you just, like, keep away from me, never come anywhere near me again as long as I live?’” (4.42-5.28).

[v] For an essay propounding the ingenious theory that these diners are actually Hooded Justice and Captain Metropolis, see Gifford.

[vi] This overarching vision is expressed by Jon in his conversation with Laurie on Mars. At this epiphanic moment, the most powerful being in the universe is humbled by the realization that the existence of human lives is already a “thermodynamic miracle”; a person doesn’t need to be a “hero” to be important. Something of this vision is also expressed by V in V for Vendetta: “Everybody is special. Everybody. Everybody is a hero, a loner, a fool, a villain, everybody. Everybody has their story to tell” (Chp 3).

[vii] In Watchmen, Hooded Justice is said to harbor neo-Nazi sympathies (II.30) and has roughed up several of his former boyfriends (IX.31). Nelson has made racist remarks about African and Hispanic Americans (II.30), and his ulterior motive in forming the Minutemen is explored in Dan Greenberg’s and Ray Winniger’s non-canonical role-playing games (see Callahan). Yet, even with these precedents in mind, Cooke’s portrayal still comes across as relentless in its negativity. Cooke isn’t the only Before Watchmen writer to try to hetero-normalize the Watchmen universe. In Len Wein’s Ozymandias, the “possibl[y] homosexual” Adrian Veidt is also “outed” as a heterosexual.

[viii] I suspect Cooke might plead that Bill’s attitude is “historically accurate” here (to make a Mad Men analogy: Don Draper is sexist, but that doesn’t make Matthew Weiner so), but the tenor of Cooke’s writing goes beyond historical accuracy. On Bill’s death, Hollis is unreserved about Bill’s integrity: “Bill was a good man and a good friend. I miss him.” (IV.5) The problem is that Cooke has done nothing in all six books to establish Bill’s goodness and friendliness except through his male-bonding scenes with Eddie and Hollis over their righteous disgust at Nelson and Hooded. This makes it hard not to infer that Bill’s homophobia is presented as being completely consistent with his goodness and friendliness.

[ix] The Bluecoat and Scout sequence is a good example of Cooke’s inability to transcend banal heroic antics even in a moment that is supposed to offer meaningful historical insights. The duo is obviously Cooke‘s attempt to comment on US treatment of Japanese-Americans during World War II. However, the duo comes across not as real people but as moralistic tools. If we compare Cooke’s cloyingly sanctimonious Scout to Moore’s refreshingly normal African-American boy Bernie, who doesn’t need to do anything heroic to convince us of his humanity and make us think deeply about the cultural construction of heroism—Bernie’s position as reader of the Tales of the Black Freighter makes him an “everyman” reader of Ur-heroic narratives—we have a decisive demonstration of what makes Cooke a mediocre writer and Moore a great one.

[x] Cooke’s moralistic pitting of the “best buddies” Hollis-Byron against the “degenerate lovers” Nelson-Hooded establishes a good-vs-bad dichotomy that the original Watchmen doesn’t support. In the reunion party at Sally’s house in Book IX, Nelson’s words clearly indicate that he has kept in touch with the mentally ill Byron: “I’d better go check outside. He should arrive soon, and I promised I’d meet him ….” (IX.11)

[xi] E.g. in the Sin City story “The Hard Goodbye”, Marv chivalrically knocks Wendy out to spare her witnessing his brutal revenge on Kevin. Rape as an act of honor is probably less common in mainstream US comics than in Japanese manga. E.g. in Kazuo Koike’s and Ryoichi Ikegami’s outrageously compelling The Injured Man (Kizuoibito), the alpha male hero’s violent sexual antics (which include the rape of a young teenage girl) are presented as unambiguously heroic. Moore’s essay “Invisible Girls and Phantom Ladies” demonstrates that he is well aware of the problems with the genre’s depiction of women.

[xii] Moore is unequivocal about this point: “He raped her. He raped her and she still had Laurie with him some years later … she had consensual sex with him some years later. And I was trying to think, is this psychologically credible? And I could see that it was—I certainly didn’t want to say: ‘Ah, she secretly enjoyed being raped,’ or something like that. But I wanted to say that it might be more complex than that …. That there might have been, despite his behavior, there might have been some part of her that responded or that she felt guilty about the response…. I’m not saying that it makes it right for him to do those things or that she is right to return to an abusive partner; but I’m saying that it happens, that it’s a real part of how humans fit together” (Khoury 117-118).

[xiii] On the whole, the portrayal of Eddie is so favorable in the franchise that one wonders if DC had given an editorial mandate to redeem his character. The whitewashing is equally evident in Brian Azzarello’s six-issue Comedian, which elevates Eddie almost to a symbol of America’s troubled conscience by charting his Kurtzian descent into the heart of darkness. Significantly, none of the books mentions the rape of Sally or the murder of the Vietnamese woman—surely a glaring omission considering that Eddie’s yearning for Laurie is psychologically explainable as an outcome of his guilt about murdering his unborn child in Vietnam. In the original, Laurie’s throwing a glass of scotch into his face (IX.21) mirrors the Vietnamese girl cutting his face with glass (II.14).

[xiv] This point is offered as a speculation rather than as a fact in Watchmen. It is based on four pieces of information: (i) Eddie warns Hooded before he leaves: “I got your number … [O]ne of these days, the joke’s gonna be on you’ (II.7); (ii) Hollis conjectures that Hooded Justice’s real identity is circus strongman Rolf Müller, whose “badly decomposed body” was found “shot through the head” (III.30); (iii) Adrian asks: “Had Blake found Hooded Justice, killed him, reporting failure? I can prove nothing” (XI.18); (iv) at the white house cocktail party, Eddie jokes: “Just don’t ask where I was when I heard about J.F.K.” (IX.20)

[xv] I have trouble following Cooke’s reasoning in this episode. The facts are simple enough: Eddie wants to get back at Hooded Justice. He disguises himself as Hooded and tricks Hollis into believing that Hooded is the paedophile Ursula was looking for. This leads Hollis to hunt down the real Hooded and kill him in a scuffle. Years later, Hollis prepares to tell all in his book Under the Hood. Before the book’s publication, he receives a midnight visit from Eddie. Eddie shocks him with an account of what really happened, and advises him that “Mr Hoover and other interested parties” would prefer a “light-hearted”, “sunny reminiscence” of the truth. Out of a desire to “protect” his friends, Hollis agrees to rewrite the book, and the version of the book excerpted in Watchmen is a “sanitized” account of the truth. I have at least two problems with this revisionist history: (i) I fail to see how the pages from Under the Hood as they appear in Watchmen would have been acceptable to “Mr Hoover and other interested parties,” given Hollis’ explicit critique of the government’s role in manipulating the phenomenon of the masked avengers; (ii) given that Cooke has already established in Book 5 that Sally is strongly against the publication of Under the Hood (Moore’s Sally also angrily reprimands Hollis for mentioning the book to Laurie at the reunion party in Book IX.12), why doesn’t Hollis “protect” Sally’s privacy by censoring the parts relating to her? If the “truth” was as Cooke had painted them, I suggest the most plausible and sensible action for Hollis would have been to abandon publishing Under the Hood altogether. My impression is that Cooke is so determined to create a cool “gotcha” moment for badass Eddie that he is willing to ride roughshod over realism, plot logic and character consistency in order to achieve this sensational effect.

Read Part 2 here.