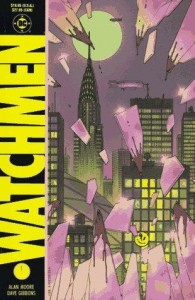

We’ve had a lengthy thread about the relative merits of Watchmen here. Lots of interesting contributions from Eric Berlatsky (my brother and an Alan Moore scholar); Marc-Oliver Frisch; Darryl Ayo Brathwaite (who wrote the original post); Chris Mautner, and just a ton of other people. For me personally, though, the highlight has been Jeet Heer’s negative take. As Ng Suat Tong said recently, Watchmen hasn’t attracted a lot of skeptical criticism. Anyway, I thought I’d reprint his thoughts here. (Noah B.)

Heer’s comments have been extensively rearranged and edited so that they can be read through with a minimum of difficulty. Please see the numbered links for the original comments. (Ng ST)

(1) The idea that Watchmen, of all things, is the greatest graphic novel ever is so alien to my experience of art that I find it fascinating. I’ve actually read Watchmen a couple of times to figure out why some people love it so. And while I can recognize the craft and intelligence that went into it, I’m still left with a work that lacks any of the humanity, humor, and depth to be found in the works of Chris Ware, Dan Clowes, Jaime Hernandez, [and] Gilbert Hernandez.

(2) [In] brief, the political critique of modern America to be found in Lint or The Death Ray seems to me much sharper than the politics of Watchmen. Both Lint and Andy are recognizable and plausible personality types whose character traits reflect dark aspects of the national psyche. That’s one example of many.

(3) [The] best argument that can be made on behalf of Watchmen [“is that superheroes and pulp narratives are a pretty important way in which we think about our geopolitics and our selves.” (Noah Berlatsky)]

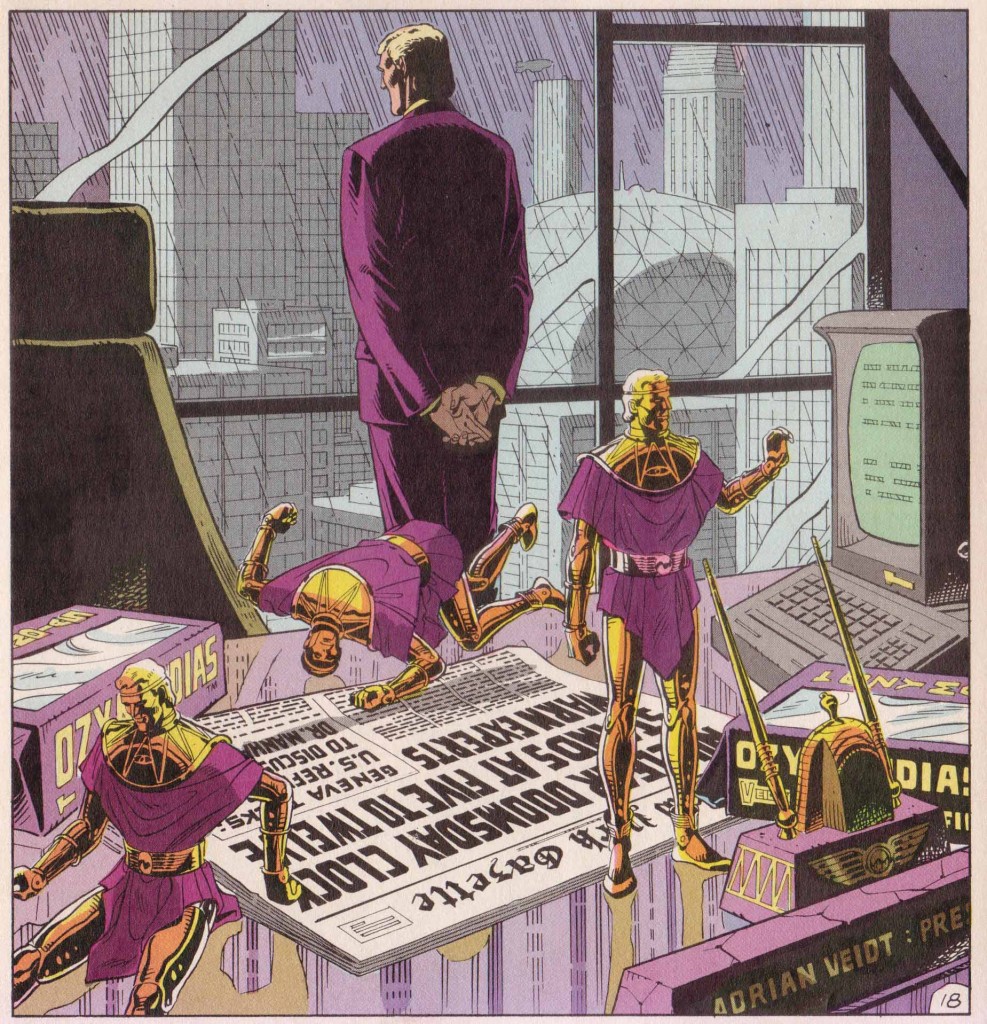

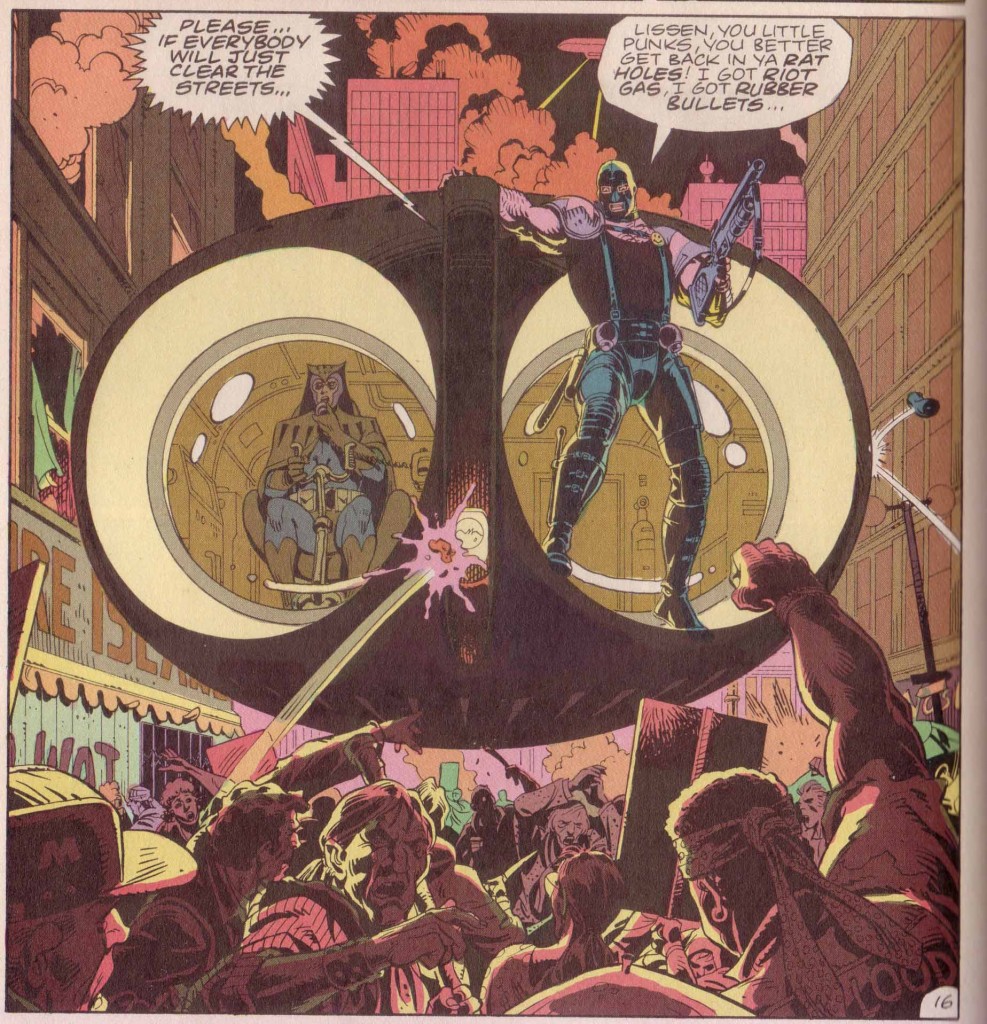

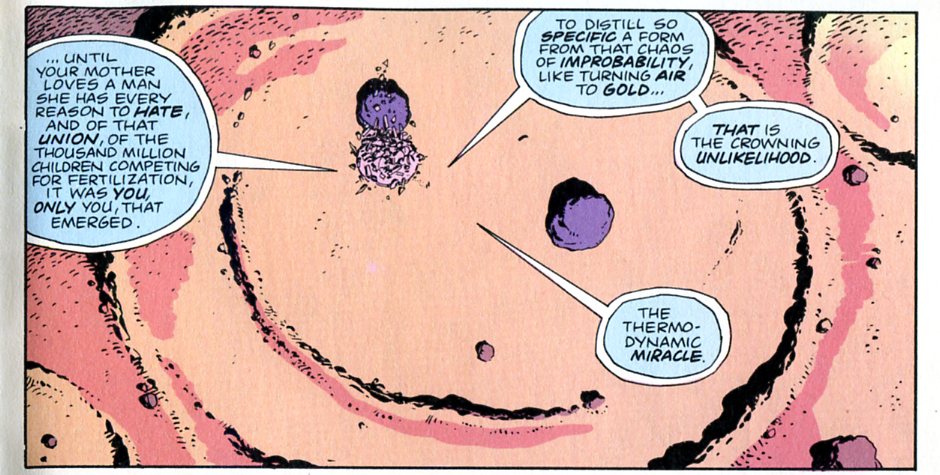

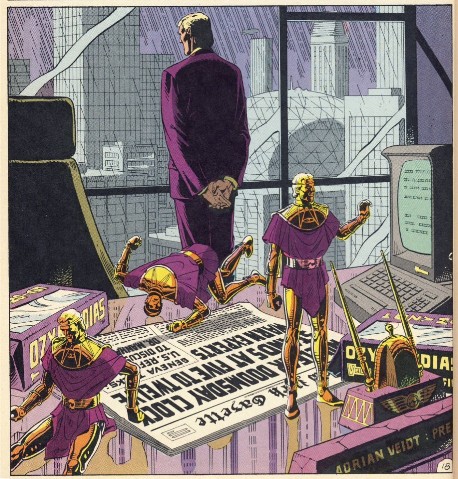

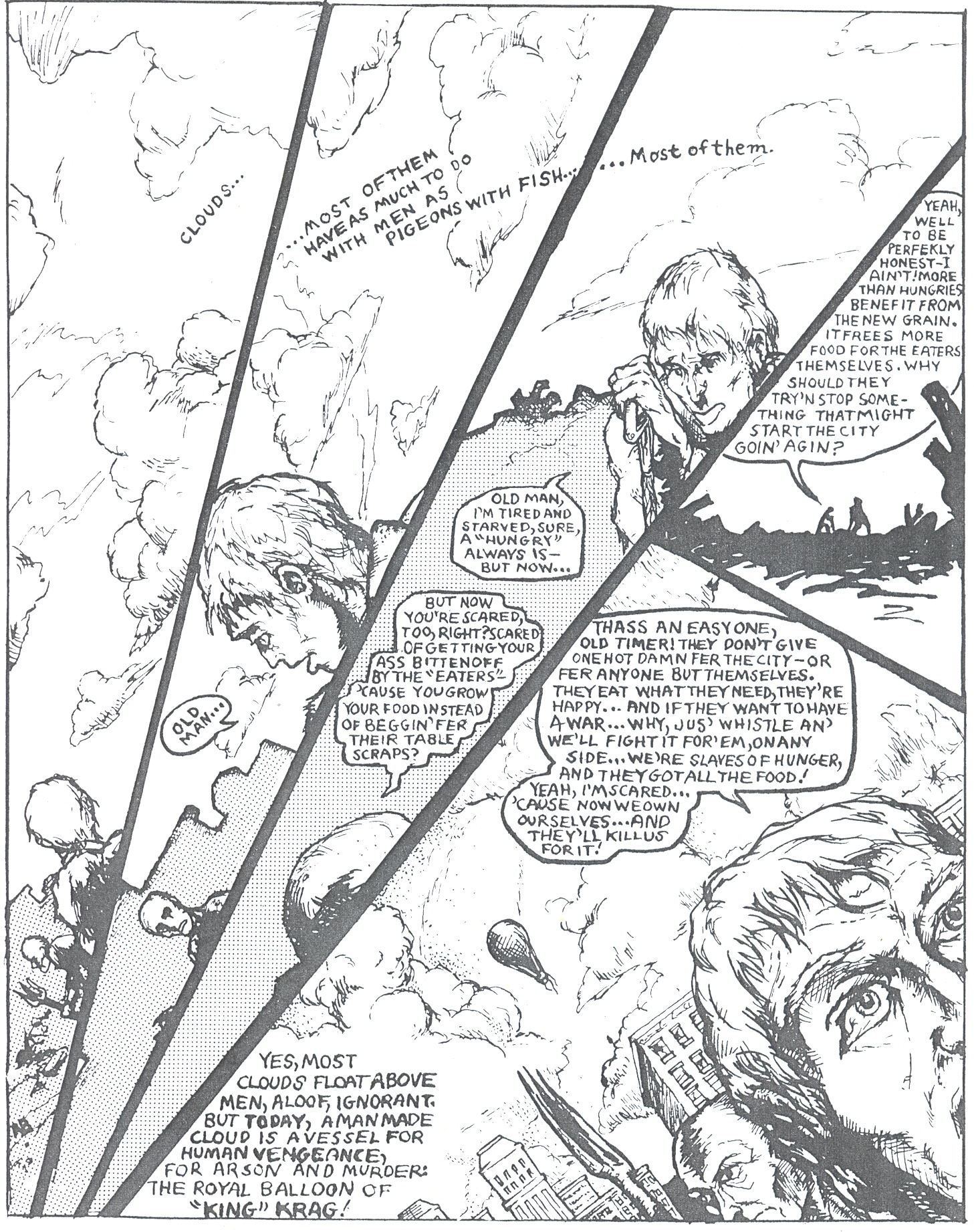

The problem is that politically the book accepts the geopolitical implications of superheroes on their own terms, so the only solution to nuclear Armageddon is the intervention of “the world’s smartest man” and the disappearance of the superhero god. For a professed anarchist, Moore has very little faith in grass-roots political activity. In the real world, the Cold War came to an end because of human agency: Gorbachev and other communists apparatchiks started to see that the regime was untenable, and were pushed for reform by dissidents while in the west Reagan had to start negotiating with the Soviets because of the peace movement. So the real heroes who saved humanity from nuclear war were figures like Solzhenitsyn, Sakharov, Lech Walesa, Gorbachev, E.P.Thompson, Helen Caldicott, etc. and the millons of ordinary people on both sides of the Iron Curtain who refused to accept the Cold War consensus. There are no counterparts to such figures in Watchmen: humanity’s fate is decided by superheroes (one of whom is willing to sacrifice millions of lives for his political agenda, another of whom is indifferent to humanity’s continued existence). There’s a despair for humanity at the heart of Watchmen which I reject both on political grounds but also because it seems callow and unearned. The darkness of Moore’s vision is ultimately closer to Lovecraft than to Kafka (think of the giant tentacled space monster Ozymandias concocts).

(4) It’s true that both the United States and post-Soviet Russia have many flaws. But fortunately there are people in both countries who are working to make things better and challenging the authorities. This type of resistance is notably absent in Watchmen. V for Vendetta is an interesting book because it does show resistance to the ruling class, but that resistance takes the form of a superhero. We can take control of our destiny but only if the superhero shows us how (and if we’re a woman, he might have to torture us along the way). There is an interesting tension between Moore’s anarchism, his philosophical determinism, and his use of the superhero genre. In my charitable moods I like to think of this tension as fruitful rather than incoherent. It certainly helps make Watchmen a little bit less programmatic than it would otherwise be.

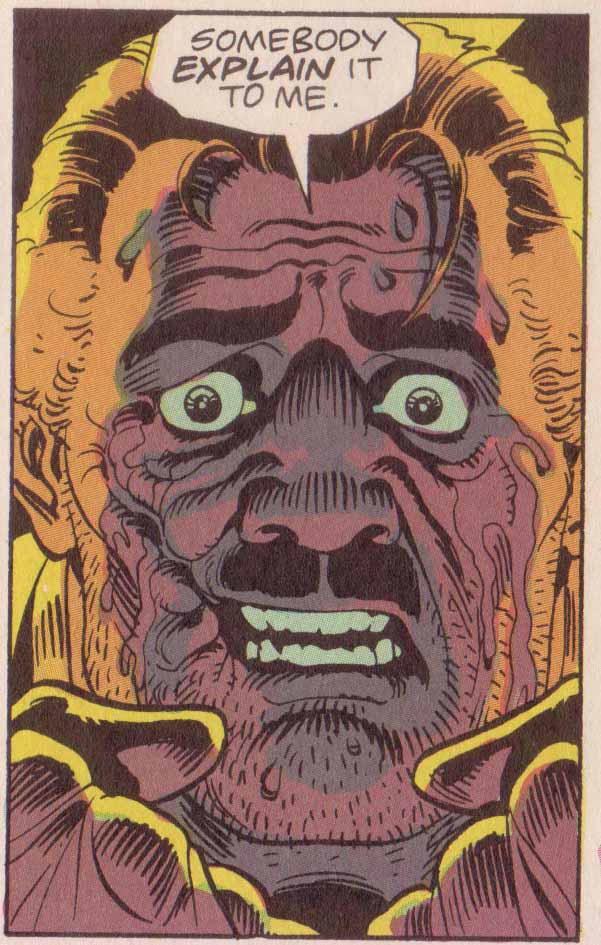

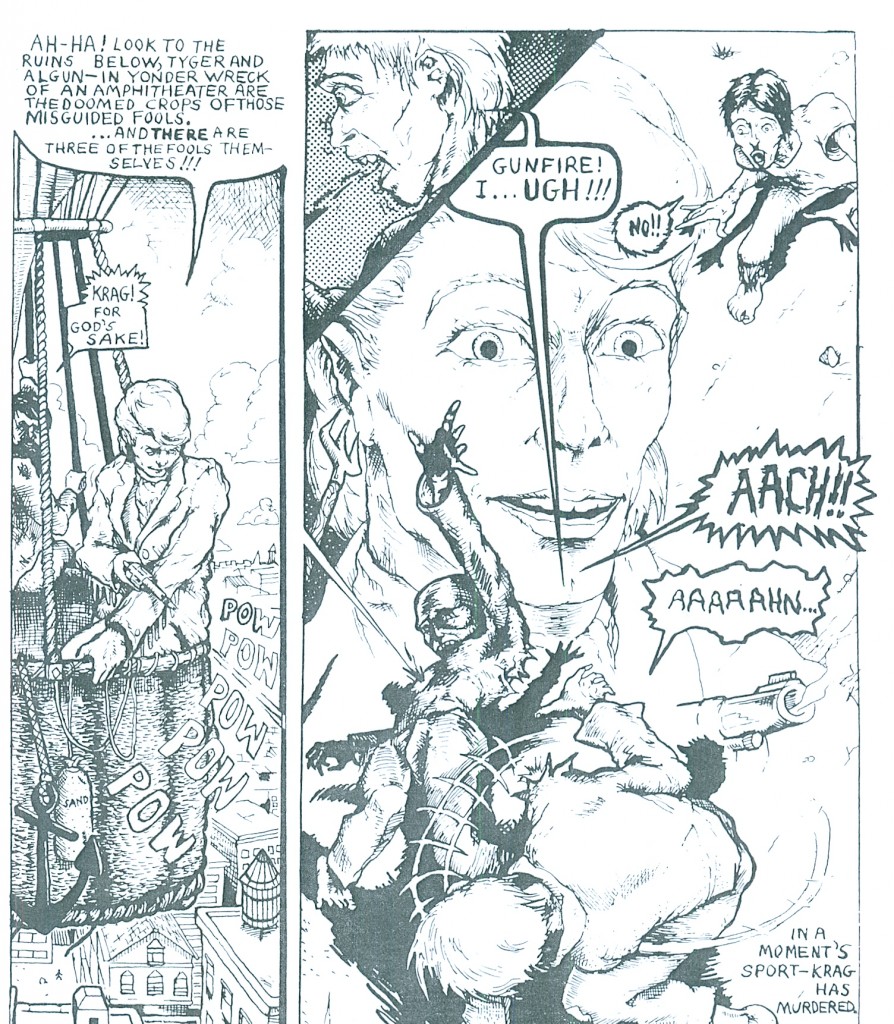

(5) [If] we take the deaths in Watchmen seriously we should regard Ozymandias as a moral monster, a veritable Eichmann. Yet even after the extent of Ozymandias’ actions are revealed, he’s treated not as a moral monster but rather as a pulp figure, a superhero-who-turns-out-to-be-supervillian. His plot is so outlandish that we can’t treat it seriously and feel the full moral import of his actions. (6) The thing is, in the context of the book Viedt is cool in the way that Rorschach is cool. Viedt has a secret hide-away, just like Superman! He’s the smartest man in the world and a gifted inventor, just like Lex Luthor! He’s always one step ahead of the game, just like the Kingpin or Dr. Doom! So as you read about his plot, Viedt doesn’t seem like Eichmann or Beria or Pol Pot. He seems like Dr. Doom or Magneto. So it’s hard to take his crime or moral culpability seriously. Or at least I can’t take it seriously. His murders don’t seem real. (By contrast, the killings in The Death Ray are chillingly believable). (7) If the squid is supposed to be idiotic and Ozymandias is an idiot and the ending a stupid anticlimax, then doesn’t that undercut the moral horror we should properly feel at the fact that within the narrative Ozymandias has killed millions of people in cold blood? We don’t think of Eichmann as an idiot who came up with an idiotic and anticlimactic scheme.

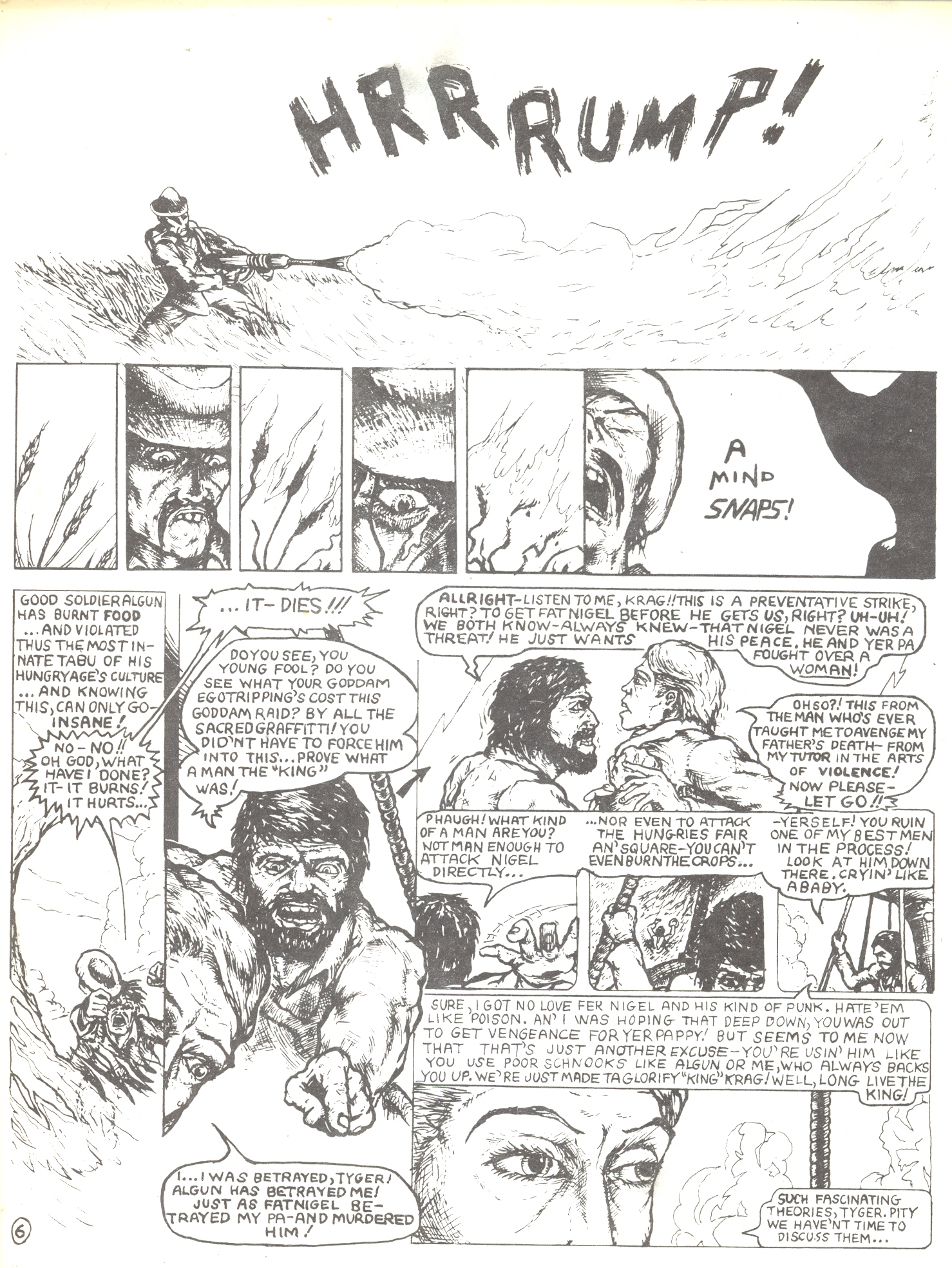

(8) It seems to me that Eric, Noah, and Mike (among others) all fall into the same habit of reading Watchmen the way Moore intended the book to be read, as an anarchist critique of superheroes and authoritarianism. But it seems to me that like many other works of art Watchmen is latent with contradictory meanings that undermine the authorial intent. It’s a story where the superheroes act and ordinary people re-act (just [as] in Shakespeare the tragic hero acts while the secondary characters and ordinary people re-act). Because characters like the Comedian, Ozymandias, and Rorschach are the agents of change and action, they are the figures that engage the imagination. It’s no accident that DC is doing “Before Watchmen” about the early life of the heroes rather than “The Early Life of the token black and lesbian characters who die in Watchmen.”

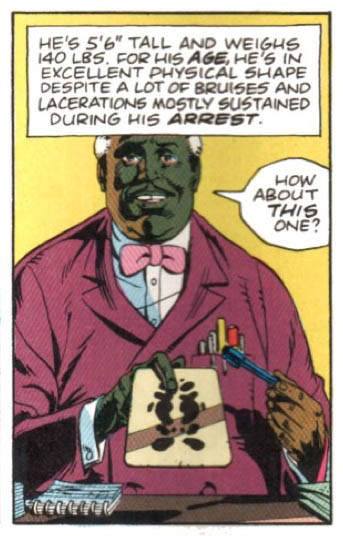

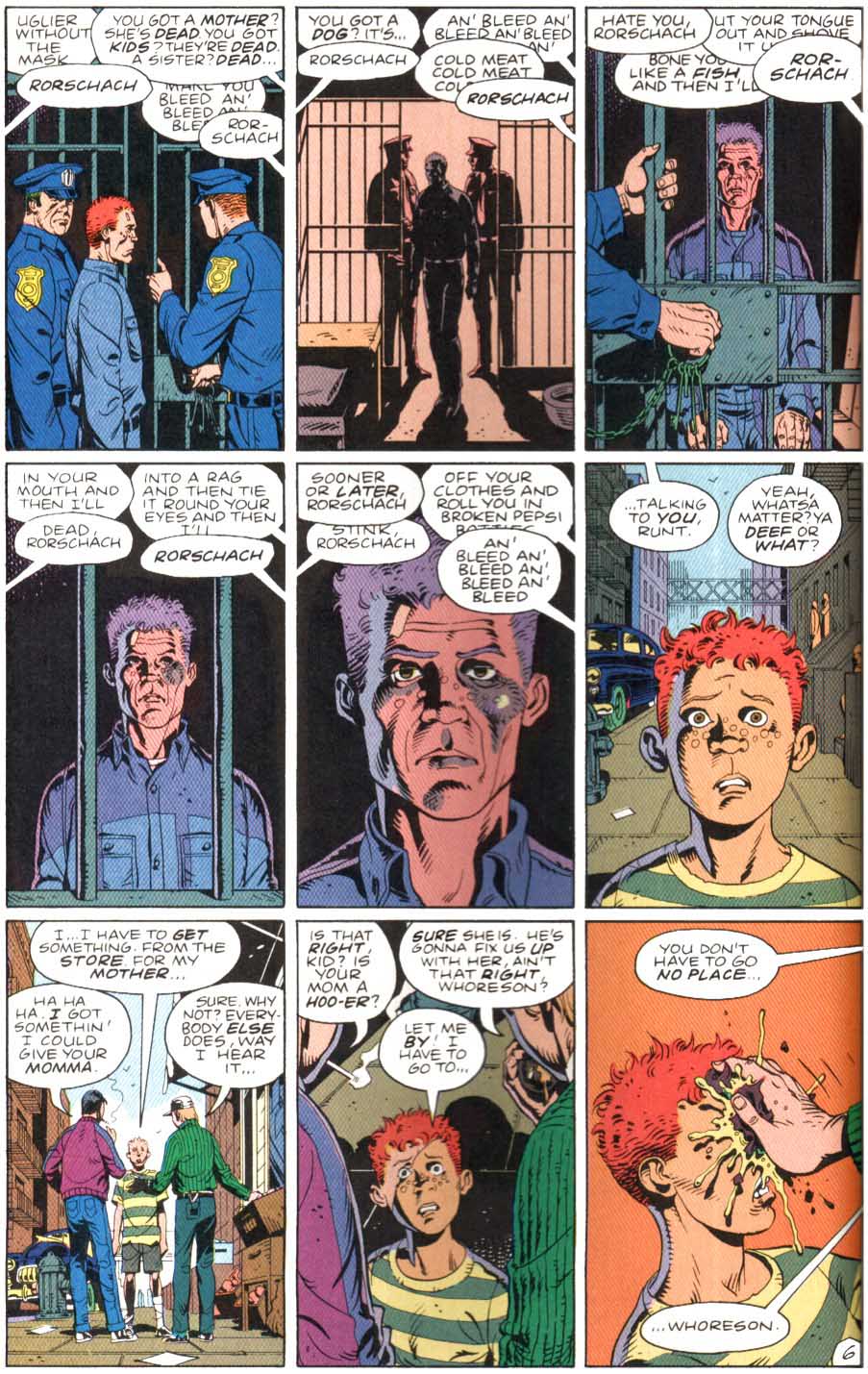

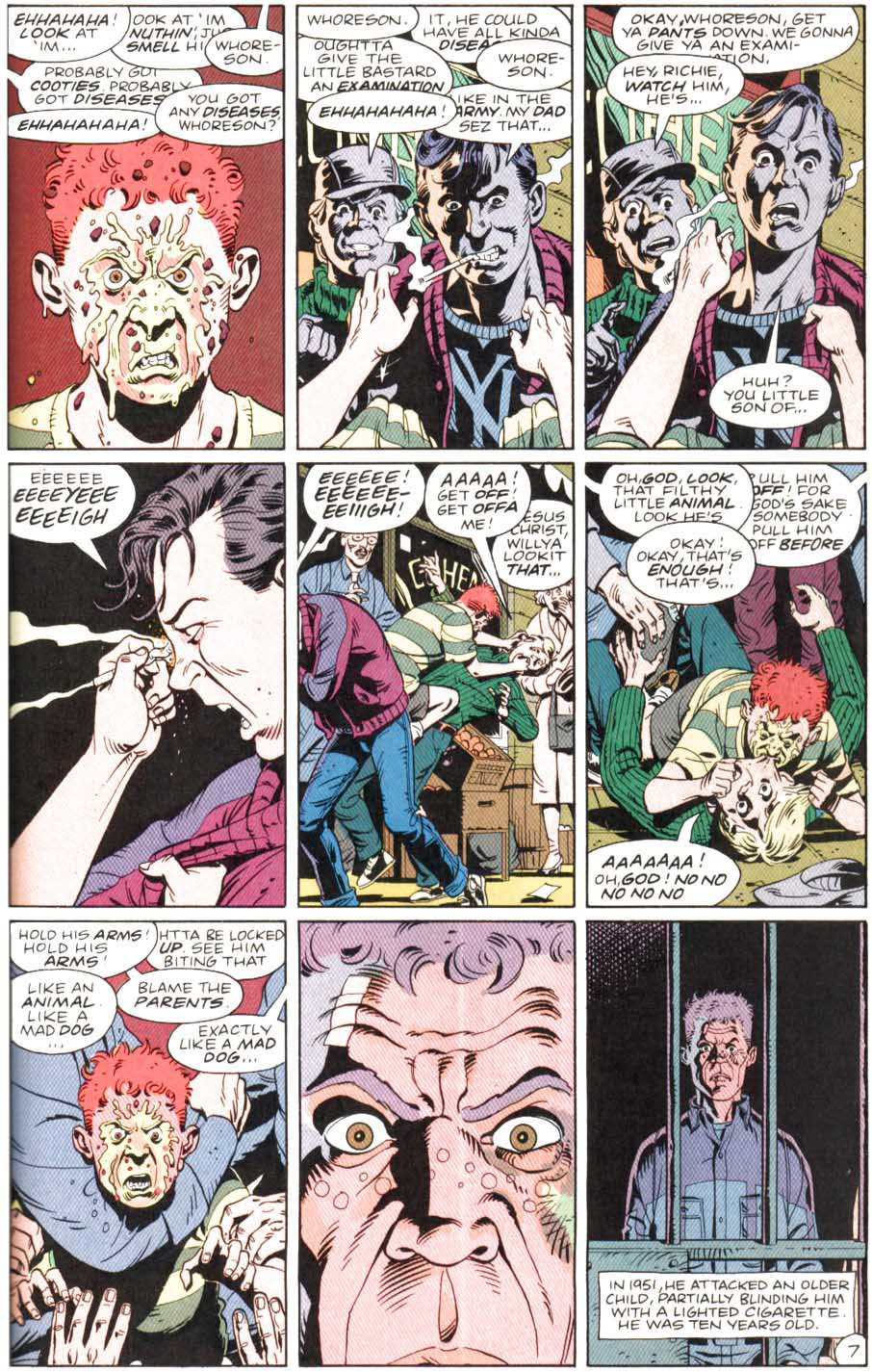

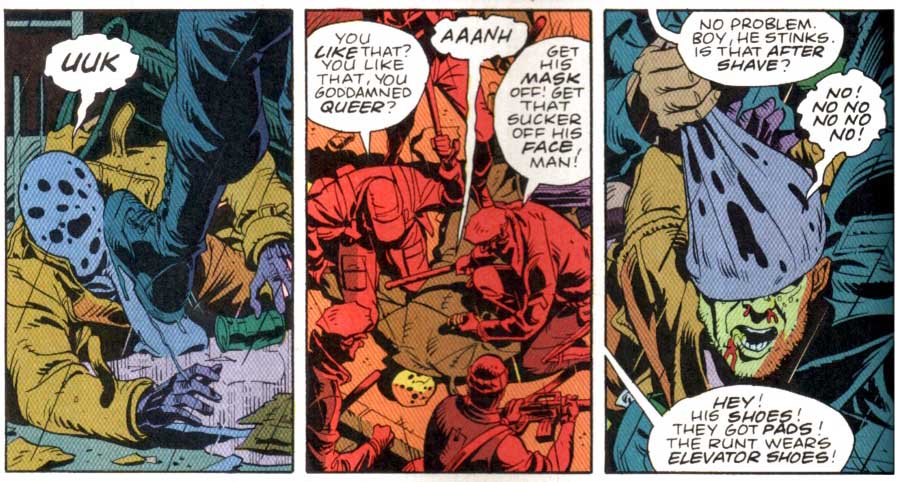

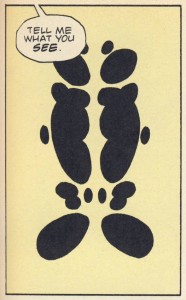

According to Mike Hunter, the fans who love Rorschach and identify with him are “dimwits” who have an “asinine” reaction. But in point of fact I think such readers understand the narrative logic of Watchmen better than the defenders on this site (Eric B., Noah, and Mike among others) do. These Rorschach loving readers understand that he’s presented as sympathetically as Peter Parker or Bruce Wayne — he’s someone who has been wronged and he’s ready to kick-ass. When you read a superhero story, your natural instinct is to identify with such a character, even if he’s a fascist loser. Moore’s authorial intent can’t overcome the logic of the genre, in part because Moore’s skills as a pastichist makes him do all the right genre moves to win over readers.

As for Rorschach being a complex character, the fact is that he takes the law into his own hands and beats people up. Am I [correct] in thinking that he also kills people? So he’s a thug — in real life he’d be horrifying but in the context of the book he’s sympathetic — because the book ultimately accepts the logic of the superhero genre. Also self-pity is a big part of the fascist mindset but Moore does not sufficiently distance us from Rorschach to make us critical of his self-pity — rather we share in it. Again, Clowes handles this better in The Death Ray.

(9) [I was just looking at Katherine Wirick’s piece on Rorschach as a rape victim.] It’s a very smart piece. This is not meant as a knock on Wirick (who makes a convincing case for how Rorschach should be interpreted) but I’m wary of accounts of fascism that start with the victimization of fascists. To the extent that fascists are victims or losers, its because they’ve benefited from systems of privilege (capitalism, imperialism, patriarchy, imperialism, racism) which are being challenged.

Mike Hunter: “…there are plenty of examples of humble, noncostumed humans, who are shown as moral, caring, striving to do the right thing, for all their final fate. The cops and psychiatrist who as their last act moved to stop the fight of the lesbian couple. The way the salt-of-the-earth newsstand vendor, as death moved to overwhelm the city of New York, protectively embraced the black kid who’d been hanging out reading this pirate comic. As their bodies merged and dissolved, tears came to my eyes…”

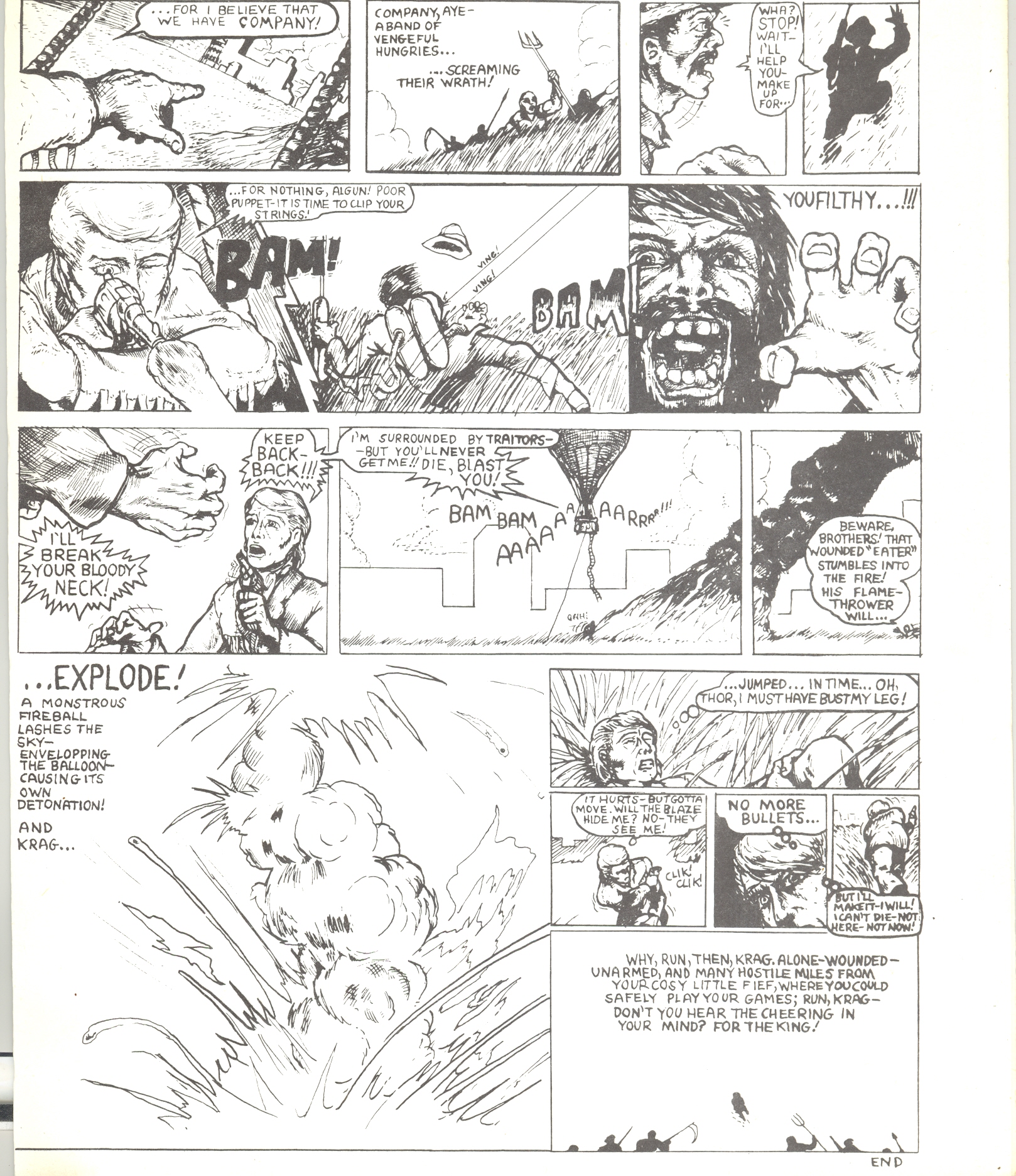

(10) Non-superheroes in Moore’s universe can try (unsuccessfully) to defend themselves but they can’t make their own history or challenge the power that be. (11) It’s fairly common in movies to spend a few moments with sympathetic figure — say a cop who is about to retire — who is then killed. This is done to establish some moral gravitas or emotional engagement on the cheap. In terms of narrative, these characters are created in order to be killed. That is what Moore is doing — being talented he does it well, but it’s still a relatively cheap effect.

In the real world, thankfully, ordinary people can and do stand up to tyranny, even if they are often defeated. (12) [In] 1984 Winston Smith and Julia do resist the totalitarian state. They are ultimately defeated and brainwashed (in a horrifying way) but despite the defeat the book hinges on the idea that there will be some internal resistance. There’s no resistance in the world of the Watchmen, only futile attempts to save a few lives in the fallout from the actions of the superheroes — but no attempt to change the system whereby the superheroes dominate or the geopolitics the superheroes are embedded in and support.

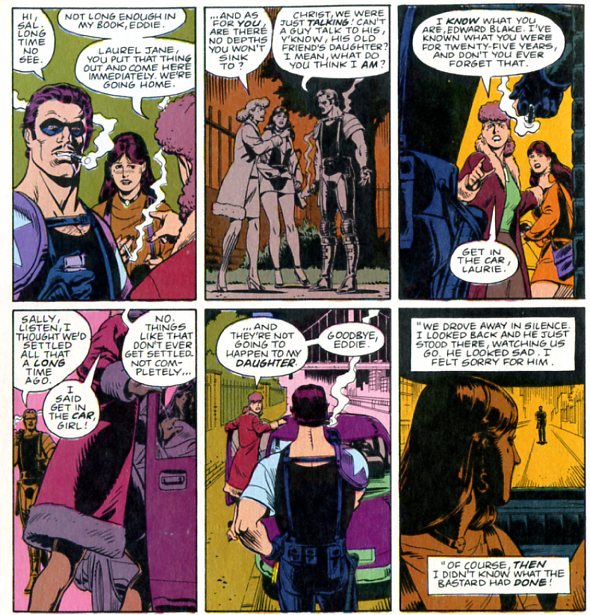

(13) Despite repeated attempts to enter into it sympathetically, I can’t accept the characters in Watchmen as human beings. Moore has them do all sorts of improbably things (like a woman falling in love with her rapist). They seem like puppets to me. There is also sorts of violence in Watchmen — rapes, murders, and even the killing of millions — but none of [this] effects me as I read the book because none of the characters are able to stake out the emotional claims that are necessary in order for us to care about the fate of fictional creations. It’s telling that many readers seem to fantasize about being Rorschach. If the violence Rorschach unleashes had any felt reality, those readers would be terrified of Rorschach and regard him as a psychopath.

(14) That’s why I brought up Clowes. He has the ability to create characters that you can both empathize with but also see their flaws and limitations — no one wants to be Andy in The Death Ray, although despite how horrible he is he remains recognizably human. The middle-aged Andy is pretty much an asshole, albeit one gifted (as many Clowes characters are) in self-justification. But the young Andy was more sympathetically presented — he’s someone in flux, with good traits and bad. The story is about the process where the young Andy starts on the road that turns him into the middle-aged Andy. And Clowes sense of how characters are shaped and formed by their environment seems much more plausible that Moore, who has a crude pop-Freudian understanding of personality formation (i.e. trauma leads to violence). The same applies to Lint — the process by which Lint becomes who he is, the way he’s shaped by his memories and decisions as well as his lifelong traits, is very finely handled. By contrast, Roscharch is just a high-brow version of The Punisher or Wolverine — a psychopath you can root for!….I just don’t see the Moore of Watchmen as being anywhere near the writer Clowes is.

(15) [As for] the rape of Sally Jupiter, just in terms of Watchmen itself, it’s a fairly minor lapse but becomes a bit more problematic because of the pervasiveness of sexualized violence towards women in Moore’s work. Again, I think there is a charitable interpretation that can be made: Moore is interested in creating genre-deconstruction and pastiche of genre material. The “damsel in distress” is a key figure in many genres and Moore is simply bringing to the fore the rape subtext that is latent in many narratives. But it’s possible to take a more critical stance towards Moore’s handling of rape as well.

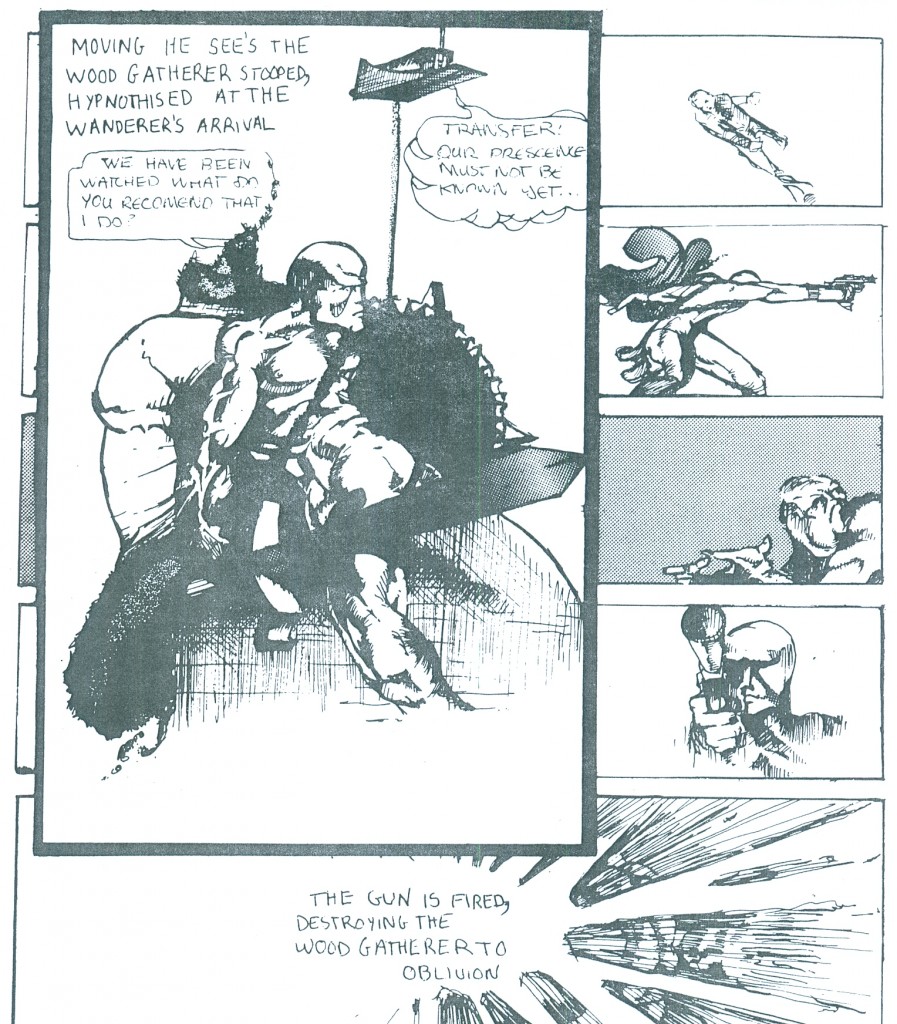

(16) [My] objection isn’t that Watchmen is a superhero comic. I have a high regard for the superhero comics of Kirby, Ditko, Eisner, Cole, and others. As I noted elsewhere Kirby offers a clue as to what bothers me about Watchmen. In all his comics Kirby created an open universe that could be imaginatively inhabited and colonized. Moore’s genre work, by contrast, seems not just closed by the airtight structures the author has created but even suffocating in the way they don’t allow the characters any freedom from the dictates of the plot and theme. A character like Maggie (in the Locas stories) or Andy (in The Death Ray) has the ability to surprise you even as they remain true to their nature. By contrast, Moore’s characters are merely pawns in the service of his agenda.

It seems to me that the critique [recently] leveled against Jaime Hernandez applies much more to Watchmen. Watchmen really is a giant Easter egg hunt. Moore is quite clever at packing his narrative with lots of little clues that readers can spend endless hours matching up in order to solve the puzzle. But I find this type of cleverness to be an arid and gimmicky exercise because the story is so utterly devoid of humanity, so utterly contrived and constructed.

____________

Okay, I think that’s it. Thanks to Jeet and all who participated. It was a fun discussion. (Noah B.)