Like comics, folk tales and fables are sometimes mistaken for children’s stories. The pretty palette and cutesy end papers of First Year Healthy belie enough abandonment, blood, and weird sexual situations to match the original Grimm brothers’ tales. That’s not to say it comes stocked with shriveled villains and plump children with rosy cheeks. There’s a baby, I guess, but it looks like the kind of thing you might find on a dusty shelf, in a jar. A quintessential Michael DeForge character, you probably wouldn’t want to touch it without latex gloves.

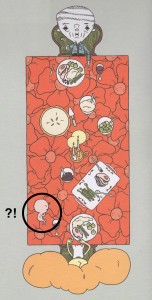

The fuck is up with this baby.

Question number one: what is this thing, anyway? Not the baby, I mean, but the book. I suppose in terms of genre it falls somewhere between faux folk and modern myth. Is it, as the synopsis on the back suggests, a “parable about mental illness”? I’m not sure that captures its central paradox, so let’s say a sinister fairy tale, or an inscrutable fable. Horror-barf meets early Björk.

DeForge’s specialty is drawing charming things with a palpable sense of disgust, a sensibility that particularly suits First Year Healthy. A slender story with big illustrations and short typed paragraphs of text, it’s reminiscent of a Little Golden Book. Plot-wise, of course, we’re pretty far afield of the poky little puppy. This is the story of a troubled young woman—our narrator—trapped in a hostile landscape filled with joyless sex and uncaring neighbors. Her chief interests seem to be wound care and walking on thin ice. Mm-hmm, literally.

“My hobbies include anything that sounds like a huge bummer.”

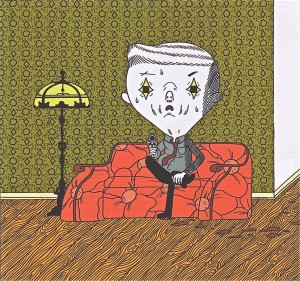

Our girl has recently emerged from an extended stay in a mental hospital. For what, we do not know, though we learn that her absence was long enough for her brothers to get married and have children to whom she has not been introduced. (Or is it possible she’s confused?) Her present-day life is full of intrigue, but it’s not exactly fraught. In fact, there’s something uncanny about the calm way in which she tells us her incredible story, which involves an orphan, several gangsters, and an enormous magic cat. All her observations seem to occur on a delay, as through a thick layer of static. Her flat affect hints at severe depression or even schizophrenia—or maybe she just doesn’t GAF.

The writing is well paced and strong, and the tension between it and the format, along with the wordless sequences with the magic cat, are probably what I would point to if someone were to get all Well, actually… about this book being not-comics. So far as I can see I stand alone in finding DeForge’s work aesthetically uneven. To me he’s at his best when he finds organic outlets for his inventiveness, like with the nightmare baby or the gray-faced gangster. The latter is the coolest thing I’ve seen in a while.

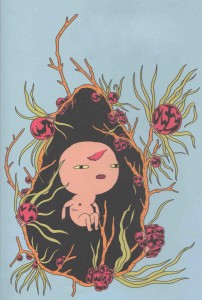

I like the artist’s weirdness less when it feels like affectation. Take, for instance, the opening image, an aggressively strange composition of some gore in a fish shop, or just the protagonist in general, whose inverse Cousin It situation is a bit much. (There are a million less ridiculous hairstyles that could’ve established a visual connection between the woman and the cat, who is—bear with me a moment—more or less her murder dæmon.) DeForge is more consistently successful with his use of color. While his tones here are earthy and muted compared to his penchant for neon, frequent shocks of pink and orange suggest that some things in our narrator’s world burn a little too brightly.

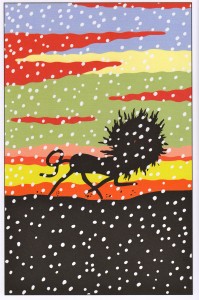

While it’s never clear how much of the story takes place in the narrator’s head, First Year Healthy doesn’t interrogate reality. The huge magic cat that silently lopes through these pages undeniably is. Many texts that explore mental illness are built around the anxious question of what is or isn’t real; that tension, and when and if it’s resolved, is what drives the plot. Remarkably, First Year Healthy is not about mental fragility. It is, rather, the story of a woman whose mind takes on a life of its own. It stalks her, but then again it eats her enemies. Is it a hallucination? Supernatural? Scary? Protective? DeForge’s answer seems to be whatever, and his utter lack of judgment is one of the things that makes this story so great.

Not for nothing, First Year Healthy is not just a portrait of mental illness; it is also a portrait of faith. Technically, it is a Christmas story (and therein are some iinteresting parallels), but what I see above all is a woman who is herself the most real and palpable thing in her universe. Her connection to the external world, and the people in it, is tenuous at best. Her closest personal relationship is with her boyfriend, who she refers to as “the Turk” in lieu of a first name. Her anonymous neighbors and nameless brothers barely register as beings in the story at all.

First Year Healthy’s focus on the narrator’s complex interiority makes it an interesting companion piece to the relentless biology of Ant Colony, DeForge’s full-length graphic novel from last year. Ant Colony’s glowing critical reception paid a lot of lip service to the young cartoonist as the next Great Pumpkin, but evidence of his genius in that volume was, to my mind, scant; its fresh look and flashes of humor couldn’t mask its Flea-grade nihilism and fundamental lack of depth. First Year Healthy is much shorter and sweeter, but beneath those trappings are big thoughts and surprising sophistication. Put another way, are we all just insects, fucking and fighting and oblivious to our own insignificance? Or is there meaning and magic in this hostile world for those who seek it? Of course the honest answer is a bit of both, but the latter makes for a more compelling story.

DeForge’s worlds are always weird but recognizable. They’re universal in that you’re meant to see yourself in them, but they’re always also Other. By design, Ant Colony explores the human condition from a sort of cold and alien vantage. First Year Healthy, which is set in the world of actual humans, is more warm-blooded. While its narrator is in many ways a familiar folk heroine—willful and self-reliant in the face of constant peril—her emotional detachment has a thoroughly modern feel. She’s brave but never spirited. Melancholy. Awkward. Alone. The strangeness of her life, which escalates quickly over just 30 pages, never fails to resonate. Like David Bowie, DeForge takes every flicker of sadness, self-doubt, insanity and total fucking loserdom you’ve ever felt and turns it into something unassailably cool.

Last month I went to see a Bowie retrospective at the Museum of Contemporary Art. It was called David Bowie Is—a perfect title, I thought, until I came to understand that the organizers approached the artist’s identity as a construct to be deciphered and explained. In breaking down Bowie’s influences, his context, and his impact, the exhibit failed to find his human heart. He is this, they told me. He is that. But the entire point of Bowie is that he can’t be reduced to a series of personas. He has always transcended any label you might wish to apply. To some degree the same is true for the rest of us mere mortals, perhaps especially when it comes to mental illness.

It’s one thing to make an old idea look new, or to make a new idea look old. It’s another to craft something unique out of what has been there all along. From David Lynch to Haruki Murakami, the weirdos who mean the most to me transform everything into something else—something other—the whole of which is greater than the sum of its parts. After weeks of thinking about First Year Healthy, I’m still not so sure what it means. Whatever. Should I someday come face to face with my own magic cat, I can only hope my first instinct won’t be to dissect it.