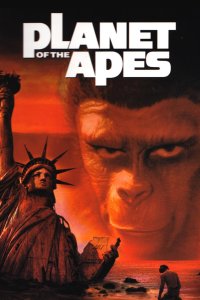

This summer’s non-superhero blockbusters are by and large a paean to anthropomorphism. Though if your options are talking robots, talking turtles, or apes eager to read a trade paperback of Charles Burns’s Black Hole, you’d do well to go with the comic book-loving apes and never look back. It isn’t “Battlestar Galactica,” but with humanity mostly destroyed and attempting to rebuild a home on what is, for all intents and purposes, a “foreign” planet, this franchise could be the space opera stand-in of your J. J. Abrams-weary dreams.

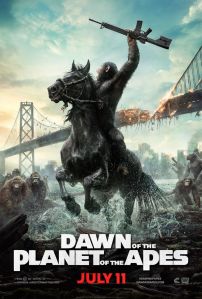

Dawn of the Planet of the Apes opens with soundbites of distressing global news broadcasts. An animated map charts the worldwide spread of Simian Flu, an airborne pathogen created by scientists to enhance ape intelligence that accidentally wiped out mankind. Individuals have a 1 in 500 chance of survival though containment seems unlikely. This initial sequence is similar to that of Dawn’s blockbuster neighbor to the north Edge of Tomorrow, and serves to bring viewers who may have skipped 2011’s Rise of the Planet of the Apes up to speed with our imminent extinction.

Ten years have passed since we last saw Caesar (Andy Serkis) claim Muir Woods as the home of enlightened apekind. The first shot set in the present is an extreme close up of his eyes, minutes before a hunt, that could have been plucked from the cutting room floor of The Good, the Bad and the Ugly. Adult apes track and chase live game as a group, relying on each other for protection from predators, while young apes remain at the homestead, learning the alphabet and the first law of ape robotics: ape not kill ape.

As for the humans, Dawn would have you believe the only people in San Francisco who survived the outbreak were genetically immune Tea Party supporters and Jason Clarke’s family (Keri Russell and Kodi Smit-McPhee). This film, like its predecessor, does not hide its disdain for the intolerant sectors of mankind. We made this bed, it says. And dammit, we’re going to lie with our uncharged iPads in it.

Frequently, Dawn’s humans are portrayed as frightened, gun-wielding children willing to slay the unfamiliar without a second thought. Gary Oldman plays Dreyfus, a man who read the words wrong and concluded with great responsibility came great need for sustainable power at any cost. He is the de facto leader of the human colony, whose crowded marketplace and heavily clotheslined sky make it appear like a live-action rendering of Agrabah.

Unfortunately, the colony is almost out of fuel. Malcolm, played by Jason Clarke, is therefore tasked with restoring a small dam located on ape territory. The goal is to generate enough hydroelectric power to maintain some semblance of human civilization. What follows is a zig-zag progression/regression of trust between humans and apes. While Malcolm and Caesar gradually develop a healthy rapport, individual members on either side grow increasingly distrustful of one another.

Unknown to the apes, Dreyfus has granted Malcolm a mere three days in which to fix the dam under the threat of launching an all-out military offensive should he fail to return. During that time, the film is often free of speech, with the majority of apes depending on sign language to communicate.

Among the many fascinating aspects of ape culture is the organic nature of its sonic reality. Theirs is a technologically devoid society. The apes have grunting and chest beating; we have strategically placed CDs by The Band. They have the slap of ape palm against tree branch; we have the rumble of automobiles and the clack of gunfire. It all seems so natural to them, existence. When a human member of the dam repair party confesses what he finds terrifying about the apes — that they don’t need power, they don’t need heat, that these advantages make them superior to man — the effect is more than a little disquieting. Dawn forces viewers to grapple with the uneasy anachronism of accepting superiority in the creature from which they evolved.

Some critics have compared the film’s quest toward peace to conflicts in the Middle East. Cited is the struggle between people who have lost everything and are desperate to hold on to what sliver remains and apes who have gained everything and are loath to lose it. However, this parallel would suggest $170 million was spent on a film in which humanity is Hamas, fitted with its own suicide bomber, demanding a right of return. Or ISIS staking claim to the Mosul Dam. While this train of thought leads to endlessly entertaining possibilities, it’s clear the humans are far from the heroes of this film– they are barely the humans; desperation has left so little intact.

To that end, while Dawn is eager to establish Caeser and Malcolm as peace-driven leaders of their factions, it develops its antagonists with equal fervor. Koba, a laboratory ape subjected to experimentation, cannot see past his former abusers and longs to destroy all humans. Both Koba and Dreyfus are easy enough to understand: If you can take something using violence — planetary dominance, in this case — why waste time figuring out whether now is the right moment to do so?

Their differences contribute as much to the deterioration of ape-human relations as their similarities. Human interaction frequently takes place via intimate one-on-one exchanges. Delicate, isolated scenes involving Malcolm and Dreyfus, Malcolm and his wife, Malcolm and his son. Conversely, virtually all ape conversations are carried out before the entire group. This communal forum serves as setting to one of the most haunting ape-to-ape encounters in the film. When Caesar informs his clan that the humans will finish their work on the dam and then leave, Koba, confounded, points to one scar on his body after the other saying the words, “Human. Work. Human. Work.”

Once Koba discovers Dreyfus’s plan to exterminate the apes he organizes a raid of the human colony. His vehemence is a thing of wonder, culminating in a 360-degree tank turret POV worthy of prestige season. All expected action tropes are present and accounted for in Dawn’s 130 minutes. The storming of a stronghold. A beautifully filmed stealth mission in a collapsing house. A final battle in a compromised structure. Primary characters falling to their deaths. There’s even the chance, 20 years later, to once more hear Gary Oldman yell the word “EVERYONE,” though this time into a megaphone. What makes Dawn different from its blockbuster ilk is the ability to craft a wide range of emotional effects due to its moral ambiguity. Director Matt Reeves, a man committed to the z-axis of his visuals, consistently steers the audience away from the binary of cheering for man or ape. This is Caeser’s film. It ends as it started: on an extreme close up of the ape’s eyes. We do as he says, and for now that is follow.