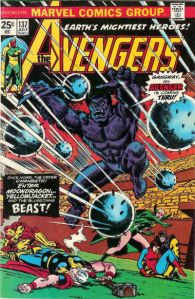

As a kid reading comics, I loved when superhero teams scrambled their rosters. For The Avengers No. 137, “We Do Seek Out New Avengers!,” Vision and the Scarlet Witch left on their honeymoon, Yellowjacket and Wasp rejoined, and Moondragon replaced the recently deceased Swordsman, leaving Hawkeye’s spot (he went off in a time machine to find the Black Knight) to be filled via an open call at Shea Stadium, where only the Beast showed up. Sounds easy, but when the Defenders televised a similar recruiting call three years later, the team was inundated with 23 would-be members, from canonical crushers Captain Marvel and Iron Man (cover appearance only) to inspired backpagers White Tiger and Prowler.

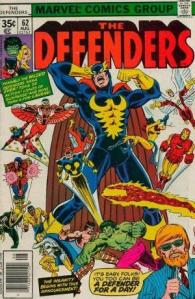

The Defenders No. 62 cover features team leader Nighthawk holding his apparently throbbing head and roaring at the impressionistically pint-sized heroes buzzing around him. Which is how I feel as I juggle the roster for a would-be course on the recent American novel. Even my open call “I Do Seek Out American Novelists!” attracts trouble, since that Canadian crusher Margaret Atwood showed up in the Shea Stadium of my brain (so does that mean I have to add “North” to the course title?). I already sent her Nobel-winning countrywoman Alice Munro home on a technicality (“Novel” not simply “Fiction”), which still leaves over twenty superpowered authors buzzing across my cover.

Writer Steve Englehart and editor Marv Wolfman weighed a dozen factors when revising the Avengers in 1975. It must be hard tossing out fan favorites like Wanda and Vision, but see how they replaced them with another married couple? And notice how they improved gender distribution by swapping in Moondragon? (Though, okay, the female count plummeted back to one when Wasp gets hospitalized in her return issue). Of course you still want some of the old standards, Thor and Iron Man, while leaving room for an unexpected choice like the newly blue-furred Beast. And what happens when you put all these costumes in the same room? How do they get along?

Syllabus-assembling makes the same demands: are these powerful books, a balanced range, what story do they tell when they stand shoulder-to-shoulder? By balanced, I mean are half by women? Are half not by white authors? It’s not political correctness but good storytelling. If a course representing the last sixty or so years of the American novel consists mostly of Caucasian men, the story is: white guys write the best stuff. That’s a stupid story, so I know four of my roughly eight slots are going to be filled by women, and four by non-WASPs. Though that doesn’t reduce the swarm of authors in Shea Stadium much.

The Englehart-Wolfman Avengers range from the team’s oldest character (Henry Pym was buzzing around in 1962) to the two-year-old Moondragon (plucked from the 1973 pages of Daredevil). When I taught a 21st century American lit course, I had about the same age range and so felt free to juggle the reading order by convenience and whim. But a span of sixtysome years requires a more disciplined time machine. Start in the 50s and bound forward decade by decade. That draws attention to gaps though, so suddenly distribution matters too. That’s one of many good reasons that Leslie Marmon Silko’s Ceremony made my first cut, as a rep of my underpopulated 70s favorites (I prefer that decade’s short stories). It also means my overpopulated 80s is a problem, so DeLillo’s White Noise could be in trouble.

And what about genre types? In addition to two insect-sized humans, the 1975 Avengers include a mutant, an alien-trained telepath, a cyborg, and a god. So I should probably hit the key literary schools too. Pynchon is an easy pick for Metafiction, though Nabokov’s Pale Fire is even more fun. New Journalism’s “nonfiction novel” list is harder to prune: Capote, Mailer, Thompson, Didion, and of course my college’s beloved alum Wolfe. But if experimental memoirs are fair game, then I want Kingston’s Woman Warrior on my team (okay, maybe I do like the 70s). So maybe it’s better to swat away all things nonfiction?

I called my 21st century fiction course Thrilling Tales and focused on the pleasant collision of traditional literary novels with the formerly lowbrow genres of scifi, fantasy and mystery. I could make the second half of the 20th century an Old Testament to that thesis. Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale is an alternate future, and Morrison’s Beloved a ghost story. Chabon won his Pulitzer for transforming superheroes into literary subject matter, and what’s The Crying of Lot 49 but a riff on thriller conventions? Egan’s genre-splicing A Visit from the Goon Squad could cap it all, and, for a truly blue-furred freak, I could shoehorn Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons’ Watchmen (I know, Moore’s British, but he was living in the States at the time of his very American collaboration, which, by the way, made Time’s ALL-TIME 100 Novels, thank you, Lev Grossman).

If you want to push the genre angle even further, swap out Flannery O’Connor for Patricia Highsmith. Or revise the subtitle to “Since World War 2” and open with Wright’s Native Son. Trade Pale Fire for Lolita and suddenly the course opens with a legion of supervillains: Bigger Thomas, Mr. Ripley, Humbert Humbert. Maybe I need to read Bret Easton Ellis’ American Psycho next? Baker’s The Fermata is a bound too far, though White Noise and its “Hitler Studies” is back in the running. I was thinking about Jones’ The Known World, but I just finished Whitehead’s Zone One, and all those zombies pair so well with the horrors of Beloved and the shadowy PTSD of Ceremony. Maybe the name of this course is American Monsters?

I was nine when I started reading The Avengers. My students are about nineteen, but they have something in common with my former Bronze Age self. Englehart and Wolfman mixed and matched their roster, knowing theirs was just the latest incarnation of a team other writers would continue to juggle for decades. But No. 137 was the first Avengers comic I ever saw. This wasn’t one version of an evolving team. This was THE Avengers. And for the students on my would-be class roster, this is the only American Novel Since 1950 course they will ever take.

And at the moment it looks something like this:

1955 Patricia Highsmith, The Talented Mr. Ripley

1966 Thomas Pynchon, The Crying of Lot 49

1977 Leslie Marmon Silko, Ceremony

1985 Margaret Atwood, The Handmaid’s Tale

1987 Toni Morrison, Beloved

1986 Alan Moore & Dave Gibbons, Watchmen

1999 Michael Chabon, The Adventures of Kavalier and Clay

2010 Jennifer Egan, A Visit from the Goon Squad

2011 Colson Whitehead, Zone One