In last week’s thread on definitions in comics, DerikB posed the question whether print advertisements count as comics. Sam Delany makes a convincing case that the question itself is impossible and probably shouldn’t even be asked, but he makes an exception for specific functional contexts where the project of definition works primarily to describe. On a case-by-case basis, examining whether or not a given definition describes a particular print advertisement (or anything else) can illuminate the strengths and weaknesses of the definition as well as the advertisement.

I responded to Derik’s comment by saying that I had a print advertisement I thought should count as comics. I called it a “found comic.” Wikipedia, not nearly as averse as Delany to defining things, observes that “the term found art…describes art created from the undisguised, but often modified, use of objects that are not normally considered art, often because they already have a non-art function.”

My usage recasts this definition for the present context: “found comics describes comics that emerge out of the juxtaposition of elements familiar from comics into material forms and contexts not normally considered comics, often because they have a non-comics function.”

Of course, the two definitions are not truly parallel: a definition of found comics that fully corresponded to found art would require that the elements of the comic be “readymade,” pulled from another context and different use, retaining the traces of that use, and making meaning through the resonance and/or contrast between the original and the artistic use. Found art depends upon that trace of the original context remaining, because the impact of found art is in the dissonant resonance between the original context and the art context.

Found art exposes the ways in which context – not form, not content, but the wall of the museum and the association with the artist – transforms a thing from an object into an art object. The sense of this depends on a cult of “the original” that is very powerful in visual fine art and less so in comics art.

Comics and literature are arts where reproductions retain the artistic value of the original (although not the historical value). They thus depend less on physical materiality and more on the creative generation and juxtaposition of ideas and images. Bricolage in comics, as in literature, pulls “objects” out of their original context and recasts them, and the act of recasting is so powerful that it transforms the meaning.

We don’t really have a concept of “found literature” because literature depends upon the context and presentation to a far smaller extent than visual art. The cut-ups of William Burroughs could be shoehorned into some definition of found literature – but it is essential to note that the conceptual signification of a cut-up novel is very different from that of found art. For this reason, although comics can certainly be made with readymade images using techniques of assemblage and collage and bricolage, I don’t see any particular analytic value in thinking of such comics as found comics.

Comics that can properly be called “found comics,” like found art, are objects whose very existence forces us to re-imagine the varied critical and cultural narratives that demarcate and generate the boundaries of what we think of when we think of comics. In that respect, they gesture toward critical positions and practices that are increasingly more and more inclusive of a broader artistic conversation, more engaged with liminal and marginal comics, more engaged with the normative critical practices of other art forms, while simultaneously allowing us, through comparison, to more finely tune our awareness and understanding of the comics at the center (a center that includes both conventionally defined art comics as well as “mainstream” comics, but not print ads).

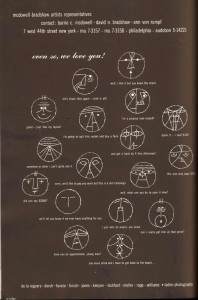

Here’s that advertisement I think qualifies as a found comic. (To read, click and zoom in.)

This advertisement appeared in the rear section of the 1950 New York Art Directors’ Annual of Advertising and Editorial Art. The last section of each year’s annual was a showcase for the trade: everything from ad agencies to typographers to paper companies took the opportunity to link their name and an impressive image in the consciousness of the most savvy and successful advertising and publishing professionals.

The agencies surely put their best foot forward in these ads, but as they were also selling a product, the work represented in that context necessarily reflected the company’s overall brand image. So to no small extent this ad represents the level of craft expected from a major advertising house, and it’s a pretty high level of craft. The faces are cubism in the guise of ‘50s flat-affect; the captions make the art director into a sort of “bogeyman wizard,” equal parts magic and intimidation. Representing the litany of criticisms and complaints the artist hears from the art director every day, each “panel” is so unique that it becomes easy for the viewer to imagine, to narrate, the day-to-day struggles of professional interaction and office life (this even without the suggestive resonance with Mad Men).

So this particular professional context certainly passes the criteria of “not usually thought of as comics.” I think I’m safe calling it “found.”

But does the ad fit any definition of comics previously advanced?

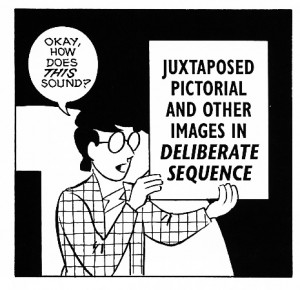

It would certainly be easy to think of it as a “single-panel cartoon.” But Scott McCloud tells us in Understanding Comics that single-panel cartoons don’t count as comics because they aren’t sequential. McCloud’s definition, building on Will Eisner’s simple “sequential art,” is “juxtaposed pictorial and other images in deliberate sequence intended to convey information and/or to produce an aesthetic response in the viewer.” Does my “found comic” fit that?

I think I’d say the intended response is not so much aesthetic as meta-aesthetic, but that could arguably count. It’s definitely not in deliberate sequence. It does, however, in contrast to McCloud’s example of Family Circus, have some of the narratological elements usually associated with sequence.

RC Harvey gives us a slightly more fitting definition (copied from Wikipedia for expedience): “Comics consist of pictorial narratives or expositions in which words (often lettered into the picture area within speech balloons) usually contribute to the meaning of the pictures and vice versa.” But it still doesn’t quite work. In my advertisement, the narrative emerges as a resonance, but it’s not IN the comic, explicitly. There’s no direct reference to it. The advertisement is allusive rather than illustrative.

Both words and pictures contribute to this resonant allusive meaning, which is other than both. So the meaning is not cycling in between the words and the pictures in some interdependent “vice versa” relationship described above; instead it’s located in this third term (which I’m sure narratology has a word for that I don’t know). The text in the ad functions less to “contribute to the meaning of the pictures” as it does to anchor and restrict the meaning of the pictures, preventing a completely visceral resonance with the drawn faces –the simplistic “identification” with cartoons that McCloud talks about – and instead directing the reader to interpret the face, not only as a specific, identifiable expression but also as a moment in a narrative that the reader can fill in from general knowledge. These are clearly cartoons, but they are not “stripped down to their essential meaning” (McCloud, Understanding Comics, p. 30.)

I don’t think this is really a problem with my print ad being considered comics. I think it’s pretty obviously comics. I think this is just a problem with the definitions – they are not functional descriptions of this thing. Yet it’s not news that resonant, allusive meaning is part of comics, or that not all characterization in the cartoon form works via a very personal “identification” with an abstract face. Meaning in The Bun Field for example is located entirely in metaphor and resonance.

If you’re “in the know,” if you’re already a comics reader, it’s clear that Harvey’s definition refers to, well, things that meet Noah’s criteria of “things we all agree are comics.” But if you’d never seen a comic, what does that definition make you imagine? What do you imagine reading Scott McCloud’s definition – or at least, what would you imagine if you encountered the text pulled out of Understanding Comics without the pictures to clarify? Is it possible that comics can only be defined by showing a picture of them? And if that’s the case, why is McCloud’s definitional project so entirely unsatisfying?

Personally, I think that McCloud’s definition is perfectly suitable for describing the interior design of the hotel restaurant where I ate at on my last business trip:

Remember the definition was “juxtaposed pictorial and other images in deliberate sequence intended to convey information and/or to produce an aesthetic response in the viewer.” I realize the obvious response is that the definition doesn’t fit because sculpture – in this case vases, mosaic, and a light differential – are not pictorial or images. But sculpture is visual art, so there is no real reason why someone who wasn’t already familiar with comics would immediately understand this distinction. And that objection becomes irrelevant once the design is photographed. Even if the design doesn’t strictly meet the definition, the photograph does.

Both the design and its photograph are sequential because of the light differential, getting brighter moving to the right in the vases and to the left on the blue lap. There are gutters and panels. You could argue that the sequence is not “deliberate” – but there’s also no way to determine conclusively that the effect wasn’t intentional. And it certainly provokes an aesthetic response.

I’m not implying that this hotel display is comics, or even found comics, necessarily. I feel certain that McCloud didn’t really intend for his definition to include it. Definitions that emphasize the print medium certainly exclude this design outright – but I nonetheless think it’s perfectly illustrative of the inadequacies of McCloud’s definition, and surely of many others.

To come up with a definition that actually fits my “found comic” advertisement, I have to go to the barest pared-down definition: Wikipedia’s page on comics uses the phrase “interdependence of image and text” to describe comics. (Their actual definition replays the “sequential art” line.) But honestly, that’s so vague that it’s not really functionally useful for understanding anything — it’s obvious just from looking at the page, so it doesn’t add any understanding to comics, and a illustrated newspaper article technically fits.

Yet, my advertisement really does look and feel like comics. I’m sure it’s some subset, like the single-panel cartoon, but it surely belongs in the comics universe. There’s definitely something else, something not captured in any of these definitions, that makes comics comics.

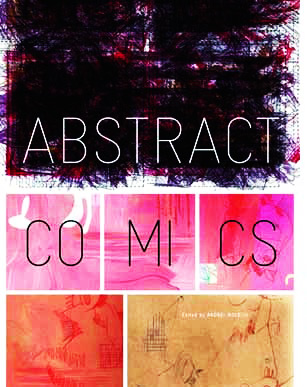

Second, the above simple version implies that any comic involves a coherent narrative of some sort. Andre Molotiu, editor of the amazing

Second, the above simple version implies that any comic involves a coherent narrative of some sort. Andre Molotiu, editor of the amazing

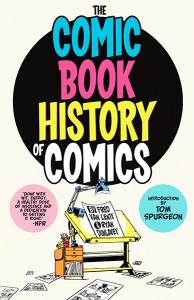

First, we have formal, aesthetic, and/or moral definitions of comics roughly paralleling traditional, pre-twentieth century definitions of art. Nontable examples include David Kunzle (The Early Comic Strip: Narrative Strips and Picture Stories in the European Broadsheet from c. 1450 to 1825, 1973), Will Eisner (Comics and Sequential Art, 1985), Scott McCloud (Understanding Comics: The Invisible Art, 1993), David Carrier (The Aesthetics of Comics, 2000), and Thierry Groensteen (The System of Comics, 1999/2007). Comparisons are easily made to Plato, Kant, and even John Dewey’s accounts of the nature of art. But, just as the second-half of the twentieth century saw a widespread rejection of any such account of the nature of art that entails that an object is an artwork solely in terms of some properties (whether formal, aesthetic, or moral) that inhere in the object itself, during the early twenty-first century comic studies has seen a similar turn away from formal definitions in favor of other approaches. Interestingly, the three main alternative approaches to defining comics match almost exactly the three main approaches found in earlier, twentieth century work on defining art.

First, we have formal, aesthetic, and/or moral definitions of comics roughly paralleling traditional, pre-twentieth century definitions of art. Nontable examples include David Kunzle (The Early Comic Strip: Narrative Strips and Picture Stories in the European Broadsheet from c. 1450 to 1825, 1973), Will Eisner (Comics and Sequential Art, 1985), Scott McCloud (Understanding Comics: The Invisible Art, 1993), David Carrier (The Aesthetics of Comics, 2000), and Thierry Groensteen (The System of Comics, 1999/2007). Comparisons are easily made to Plato, Kant, and even John Dewey’s accounts of the nature of art. But, just as the second-half of the twentieth century saw a widespread rejection of any such account of the nature of art that entails that an object is an artwork solely in terms of some properties (whether formal, aesthetic, or moral) that inhere in the object itself, during the early twenty-first century comic studies has seen a similar turn away from formal definitions in favor of other approaches. Interestingly, the three main alternative approaches to defining comics match almost exactly the three main approaches found in earlier, twentieth century work on defining art.

Thus, the work on defining comics has closely mimicked earlier debates about the definition of, and nature of, the larger category of art (presumably, all, most, or at least typical comics are artworks – even if possibly bad artworks – solely in virtue of being comics). This much seems undeniable, but it also seems somewhat problematic. After all, sticking solely to approaches and strategies that appeared plausible when used to define art is only a wise strategy if we have some sort of prior conviction that the properties and relations that make an object an artwork (i.e. that explain the artwork/non-artwork distinction) are the same properties and relations (or at the very least, the same kind of properties and relations) that make an object a comic (i.e. that explain the comic/non-comic distinction). And to my knowledge no argument has been given that this is the case. As a result, it behooves us to ask if comic studies has been too traditional, and too unimaginative, in this regard. Isn’t it possible that we could be convinced that there is an adequate definition of comics, but also convinced that such a definition should look very different from extant attempts at defining art (i.e. it would take very different kinds of factors into consideration)? And, more to the point, isn’t it possible that such an attitude could be correct? If so, then the close parallel between work on the definition of comics and work on the definition of art seems unfortunate, since it seems to ignore this possibility in favor of recapitulation of past history.

Thus, the work on defining comics has closely mimicked earlier debates about the definition of, and nature of, the larger category of art (presumably, all, most, or at least typical comics are artworks – even if possibly bad artworks – solely in virtue of being comics). This much seems undeniable, but it also seems somewhat problematic. After all, sticking solely to approaches and strategies that appeared plausible when used to define art is only a wise strategy if we have some sort of prior conviction that the properties and relations that make an object an artwork (i.e. that explain the artwork/non-artwork distinction) are the same properties and relations (or at the very least, the same kind of properties and relations) that make an object a comic (i.e. that explain the comic/non-comic distinction). And to my knowledge no argument has been given that this is the case. As a result, it behooves us to ask if comic studies has been too traditional, and too unimaginative, in this regard. Isn’t it possible that we could be convinced that there is an adequate definition of comics, but also convinced that such a definition should look very different from extant attempts at defining art (i.e. it would take very different kinds of factors into consideration)? And, more to the point, isn’t it possible that such an attitude could be correct? If so, then the close parallel between work on the definition of comics and work on the definition of art seems unfortunate, since it seems to ignore this possibility in favor of recapitulation of past history.