Has anyone “really” read Action #1?

This question — on the face if it, a rather strange one — was raised by cartoonist and scholar Don Simpson, comic book artist and art historian, on the COMIXSCHOLARS-L list serve maintained at the University of Florida just a few days ago. (And if you haven’t signed up for the list yet, what are you waiting for? After all, the only requirement for membership is an intellectual interest in comic-art.) The context for Don’s question was a thread devoted to what is nowadays an increasingly contentious issue for lovers of all kinds of literature: the shift from print to digital culture. More specifically, we were discussing the aesthetic and formal consequences of that shift, debating the losses and gains, and considering the question of when and whether the transformation in the material instantiation of comics (from print to screen) constitutes a fundamental transformation of the comic art form itself. (I say “we,” but the truth is I was mostly lurking, while letting others handle the heavy lifting; my usual mode.)

This question — on the face if it, a rather strange one — was raised by cartoonist and scholar Don Simpson, comic book artist and art historian, on the COMIXSCHOLARS-L list serve maintained at the University of Florida just a few days ago. (And if you haven’t signed up for the list yet, what are you waiting for? After all, the only requirement for membership is an intellectual interest in comic-art.) The context for Don’s question was a thread devoted to what is nowadays an increasingly contentious issue for lovers of all kinds of literature: the shift from print to digital culture. More specifically, we were discussing the aesthetic and formal consequences of that shift, debating the losses and gains, and considering the question of when and whether the transformation in the material instantiation of comics (from print to screen) constitutes a fundamental transformation of the comic art form itself. (I say “we,” but the truth is I was mostly lurking, while letting others handle the heavy lifting; my usual mode.)

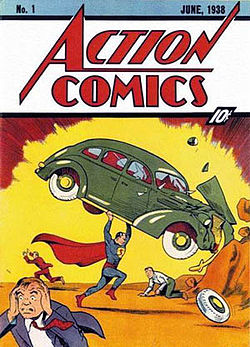

The terms of the debate may seem rarified, but the stakes were high. For example, if a given comic was originally designed for the medium of print, and you have “only” read it in an electronic format on a screen, is there a sense in which it might be said you have not “really read” it at all? (And I apologize now for the proliferation of scare-quotes in that sentence; I’m just trying to avoid leading the witness. As I hope will become clear, my purpose is not to diminish the glories of the digital archive, nor to romanticize the encounter with print, but to insist nevertheless that the differences between these two modes of transmission are worth thinking about.)

The challenge of this question will be familiar to anyone who has ever debated film with a true cinephile; it’s a variant on the insistence that if you didn’t see a movie in a real-live public movie theatre, then you didn’t really see it. It is hard not to respond to such challenges defensively; after all, they question the validity of our experiences, implying that our encounter with the artwork in question was in some way impoverished, and hence less than fully legitimate. Very quickly, such conversations can degenerate into debates about the relative merits of the opposed technologies of transmission, and the larger, more abstract questions — “what does it mean to have ‘seen a movie’?” or “what does it mean to have ‘read a comic’?” — get sidelined.

But Don hit upon a provocative way of re-framing the debate. Instead of contrasting print with digital comics, he pointed out that there is obviously a difference between reading a copy of Action #1 from 1938, and reading a facsimile or reprint. But while the majority of people have not had and will never have the first experience, Don felt that “one would be hard pressed to argue that of the thousands if not millions who have read some kind of facsimile edition of greater or poorer quality are somehow missing out on some ontological dimension of great import.”

Partly because I just like playing devil’s advocate, but more because I was inspired by Don’s initial observation — that hardly anyone alive today can be said to have “really” read Action #1 — I fired off a response to the list suggesting that there were some important and even fundamental (if not necessarily ontological) dimensions worthy of our consideration when comparing the experiences of these different readers. Good ol’ Noah Berlatsky read it, and invited me to resubmit my thoughts here; and so, for what it’s worth, I offer up the ruminations that Don’s provocation inspired in me, only slightly tweaked for public consumption.

__________________

Whether you can afford to read an insanely priced original copy of Action #1 (and that oxymoronic phrase, “original copy,” already suggests that we are in philosophically paradoxical territory), or whether you have read a facsimile of the entire book, or whether (like most of us) you have only read the Superman story, sans commercials and accompanying adventure strips, in a modern reprint collection such as the DC Archive Edition — or (indeed) whether you have read Action #1 in some version online — it was clearly a very different experience to read Action #1 in the late Spring or early Summer of 1938.

That difference is obviously partly a function of history — which is why it wouldn’t be the same thing to read the “original” comic today, even if you happen to be one of those members of the 1% who can afford to buy that particular thrill. But for most of us, the different reading experience is not simply or only a matter of temporal distance. The text that we have read is likely to be significantly materially different from that of the “original”: if we have read a print version, then we are talking about different paper stock; different standards of line reproduction; different color quality; different weight and heft, whether we are reading a hardcover or paperback; different surrounding contexts (most likely other Superman stories, rather than the generic mix of adventure tales that first accompanied the Man of Steel on the newsstands). If we are reading an electronic version, our experience will be still further transformed; we may have gained the ability to expand single panels to many times their usual size with the swipe of a finger, for example, even as we will have inevitably lost the phenomenological dimensions of the encounter with print.

I’m not sure that any one of these reading experiences could be said to be more authentic or legitimate in some absolute sense than any other. But on the other hand, I do think that when we write about comics critically, and especially when we teach them (something I am privileged to do as part of the University of Oregon’s Undergraduate Minor in Comics and Cartoon Studies), we are obligated to at least think about the experiential difference that these material differences make.

When I teach the first year of Superman stories from Action, using the (wonderfully practical and reasonably priced) Superman Chronicles Volume One collection from DC, I want students to understand that while my choice of text has put some interesting old comics in their hands, their reading experience will nevertheless be radically different from that of Siegel and Shuster’s first audiences. I therefore also ask them to read some excerpts from Gerard Jones’s Men of Tomorrow, so they can start to get a sense of those lost historical contexts. (Some of these are harder to invoke than others. For example, imagining the world before TV may be difficult for many of my students, as it is for me; sadly, however, it is easier for my students to identify with the experience of living through a profound economic depression.) I try to recreate some pop-cultural contexts, too, by lecturing about and providing examples of some of Superman’s literary and comic-strip precursors — things that were just part of Jerry and Joe’s consciousness but which are obviously obscure to most contemporary teenagers (newspaper adventures strips such as Alex Raymond’s Flash Gordon, SF pulps, excerpts from Philip Wylie’s crappy novel, and so on).

But we also have an archive of Golden Age comics at the UO (left to us by Gardner Fox himself — and yes, it was a good day when I discovered that resource!). This archive includes copies of Action and Superman from as early as 1940 (as well as examples of early Flash Comics, Adventure Comics, and other cool stuff), and the last time I taught my course on the “Modern American Superhero” I built an assignment around it. The students were required at some point in the term to go to Special Collections, where the books are housed, and order up a 1940s superhero comic — I didn’t even specify a title — and then asked to write about the different experience of reading the “original” comic versus reading the modern reprints they have been assigned.

These essays were a treat to read. For a start, the students tended to write with more sensory and tactile awareness than was the norm in their other papers. They would find themselves describing the feel of the paper, even the smell of the paper, and the different quality of the colors as they appeared on newsprint. (Which is to say, they responded with enhanced aesthetic awareness, from the get go.) Almost without exception, they seemed compelled to talk about the strange advertisements and curious government-sanctioned messages they encountered interleaved between the stories. (Which is to say, they responded with a heightened sense of political and cultural transformation.) And many of them then went on to draw illuminating contrasts between the superhero strip that headlined the book they had chosen, and the accompanying adventure strips that made up the anthology in their hands. (Which is to say, they came away with a more acute sense of the generic contexts in which superhero comics were first established.) Some talked about the comics as paradoxical “time machines” that provided them with a glimpse of a lost historical reality even as they paraded a cavalcade of fantasies that never were.

Again, I would not mean to suggest that these students were having something closer to the “original aesthetic experience” of a person who read superhero comics in the 1940s — or to suggest that the experience of such a person should be regarded as more “authentic” than that of a contemporary reader. This discussion is not (or need not) lead to the reassertion of some metaphysics of presence by the backdoor. My point is simply that the students were having a different experience from that of reading a reprint or a digital scan. Moreover, this experience is one that, from a pedagogical and scholarly point of view, might be thought of as educational and productive — an experience that deepened their knowledge and appreciation of the history of the comics form, and the processes of comics reading.

It was also a privileged experience — no question. (I hadn’t read many golden age books before I discovered this archive, either.) And (to bring us back to the question of whether it matters whether you have read an “original” comic if you have “only” read it online), it is by no means obvious to me that many salient aspects of this experience could be reproduced digitally — even if we were to scan the “original” books in their entirety.

If I may be allowed to invoke a parallel from my own education: when I was trained as a scholar of Renaissance Literature, I was required to spend some time setting type by hand for an old-school letter press, working from a piece of manuscript written in Elizabethan secretary hand. The project was not scrupulous in its historical verisimilitude; the press itself dated from the 18th century rather than the 16th, for example, although the systems were still close enough for the purposes of my teachers. I blush now to recall how petulant and dismissive I was about this assignment at the time; it seemed only a short step away from dressing up for an SCA gathering, and I couldn’t imagine what I would learn from it. But actually this forced encounter with an older printing technology actually taught me a huge amount, very quickly, and in a way that stuck. I learned in a practical way about the differences between early modern printed books and modern mass-market paperbacks. I learned how errors occurred, and how difficult it was to correct those errors even once they had been noticed. I felt first hand the temptation to set verse as prose, for reasons of expedience, and to tamper with authorial spelling and syntax rather than undo and re-set a whole page of type to correct a mistake I had noticed too late. I came to understand in a phenomenological way the differences involved when reading, say, a modern edition of Othello versus the (radically different) print versions that we have from early 17th century. In short, it was an experience that made me a stronger reader of Shakespeare (and other early modern writers), from a scholarly point of view — much better placed to interpret and contest contemporary editorial choices.

So: at the risk of repeating myself — to ask students to be aware of the differences that both material and cultural contexts make in the reception of texts is not necessarily to argue for the privileged “authenticity” of a particular instantiation of the text. It is not to elevate the experience of print over the experience of digital texts on the grounds of a mystified or fetishistic understanding of the “original” book. It is simply to insist that how and when and in what form you encounter something makes a difference; and to insist further than once you become aware of those differences, your whole response to that artwork can change.

As comics scholars today, we live in a true “golden age” of reprints from quality publishers such as IDW and Fantagraphics — while the digital archives of sites such as comicbookplus.com have made available an incredible range of rare materials: comics I had only read about or seen cover images for; comics I never knew existed. Faced with such an embarrassment of four-color riches, it is easy to forget (or repress) the potential difference that the material instantiation of those comics makes to the reading experience. But Donald Simpson’s observation that, in an important way, very few of could be said to have “really read” Action #1 reminded me of those differences (even though I think Don was ultimately making a different point).

It’s a counter-intuitive observation that raises issues that, for me, are more epistemological than ontological; it goes less to the question of “What is a comic?” and more to the question of “What is reading?” What do we mean when we say we have read something? Again, the question may seem rarified and abstract, but the stakes remain high (I personally believe the world would be a better place if more people asked how it is they think they “know” stuff, after all).

To put it another way; while most of the time it’s probably not that big a deal, there are circumstances in which it might be considered a problem that most people who would claim to have read Action #1 have in fact “really” “only” looked at a modern reprint of the Superman story that Action #1 contained. Not to say that this itself would not be a worthwhile thing to have done; in fact, if you have done it, then if nothing else you have already met the minimum requirement for one of my classes. But the kind of reading I am trying to encourage is finally a little more imaginatively and historically engaged than that.

For the record, and lest I be misunderstood, it may be worth reiterating that I have no problem with digital comics, and am not speaking against them. I read quite a few and when print versions are unavailable or prohibitively expensive I require my students to read PDFs on their computers.

But I think that as comics scholars and critics, we need to remember that the experience of reading a comic digitally is not the same as reading it in print; and that the experience of reading a reprint is not the same as encountering an “original” comic; and further, that reading a printed comic is not the same as actually being lucky enough to look at original production art (something else I try to make possible for students by bringing in examples of original comic art, and organizing exhibitions of the stuff). Good critical work on comics must remain conscious of these differences. This is not an elitist position or a metaphysically dubious one. It is merely a scholarly one.