La storia dell’Orso (the bear’s story) by Stefano Ricci

Some comics artists find the word balloons annoying. To them, it’s an intrusion in the purity of the drawings; holes in the composition, so to speak. This pushed them to find solutions to minimize the word balloon’s weight in the panel. Hal Foster, below, for instance, eliminated the word balloon altogether including captions and spoken captions (in italics between quotation marks) in the same caption box.

Hal Foster, “Prince Valiant” Sunday Page, December 21, 1952.

Hal Foster, Prince Valiant Sunday Page, January 7, 1956. Another procedure used by Foster: the elimination of the caption box putting the caption in a negative space.

Federico del Barrio, below, used the upper part of the panels, contiguous to the gutters, with a very discreet tail, to put the direct speech, freeing the images from the balloons’ intrusion.

Felipe Hernandez Cava (w), Federico del Barrio (a), Lope de Aguirre, La conjura [Lope de Aguirre, the conspiracy], Ikusager, 1993.

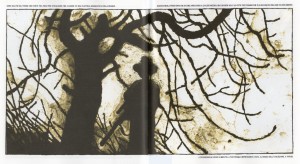

La storia dell’Orso by Stefano Ricci was first published in French as L’histoire de l’Ours (Futuropolis, 2014). The Italian edition, by Quodlibet, followed shortly after four refusals from other publishers. It definitely is, in my opinion, one of the best graphic novels published last year.

Stefano Ricci, La storia dell’Orso [the bear’s story], Quodlibet, 2014.

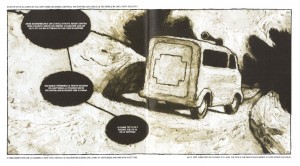

La storia dell’Orso is a graphic novel in cinemascope: every drawing is a double-page spread. Stefano Ricci has nothing against word balloons (his are computer lettered white fonts on a dark sepia background – the color of the grizzly), but, most of the times, he strategically puts them – single or coupled by connectors – on the right or on the left hand of his drawings.

Stefano’s innovation is the use of the page margin (see below) to achieve a counterpoint of narrative voices, sometimes diverging and sometimes converging with the images and the word balloons.

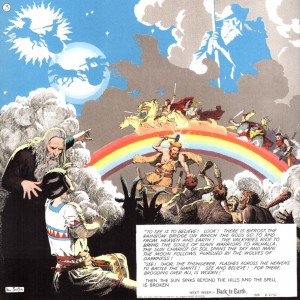

The bear referred to in the title is Bruno (a name that also means “brown” as in “brown bear”), famous in Italy, Slovenia, Austria and Germany for a while in 2006. Bruno was born in Italy as part of the Life-Ursus project in Adamello-Brenta park. It roamed between Austria and Germany for a while until, in spite of the World Wildlife Fund’s efforts, it was hunted down in Bavaria.

Stefano Ricci was living in Germany (Hamburg) at the time (he is Anke Feuchtenberger’s partner) and so, in his own words, connected with Bruno’s story at some level.

There are five main stories being told in the book: Bruno’s; Stefano’s (a Ricci alter-ego who writes letters to Stella reporting his travels in Pomerania – these are readable on the page margins) and is also a rabbit performing community service in an ambulance; Enrico [Tinti]’s and Sirio [Ricci]’s life stories during the American invasion of Italy in WWII (Enrico and Sirio were fascists who deserted the German army); Manfred’s (during the fall of the GDR). Bruno’s and Stefano’s stories are the only ones being enacted, all the other stories are told in the first person to Bruno or Manfred. Another story was told by boars on one of Manfred’s tapes. Yet another narrating a dream is told to Bruno by Anke (a Anke Feuchtenberger alter-ego).

Anke and Manfred (an alter-ego of Heinz Meinhardt, a GDR ethologist) are the only humans who help Bruno.

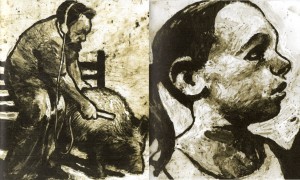

Manfred and Anke

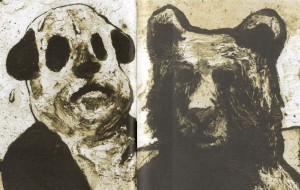

Humanized animals (a grizzly bear, a rabbit, a chimpanzee, a dog), boars that talk: we must be in the fable realm. Stefano helps the reader, who expects verisimilitude, to decode the visual metaphor: Renzo, the ambulance driver and Stefano’s co-worker, calls him “the rabbit” because, according to him, Stefano is always scared. So, this is the ages old procedure of disguising people as animals giving them the latter’s humanized character traits. The boars though, are just wild boars, it’s Manfred who understands them. (This isn’t the time nor place to study all the very complex focalizations of this graphic novel, but this is one of the most interesting: the reader reads the boars’ speech balloons with Manfred’s mind.)

Bruno as man-dog-panda at the beginning of the book

and Bruno as grizzly bear, after hibernating, at the end.

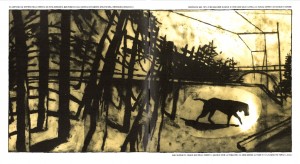

When characters just tell their stories talking heads were to be expected, but are out of the question for Stefano Ricci. What he shows us are the storytellers talking while they walk in the landscape. Or, even more interesting, in one of the sequences the words have one focalization (Ernesto’s) and the drawings have another (Bruno’s or the ocularizer’s when it’s following Bruno). The landscape, by the way, is a true character. It is one of the most important characters even…

Stefano Ricci’s drawing style reminds its roots in animation — the paint-on-glass technique specifically. It’s interesting to note, as an aside, how many avant-garde European comics artists were seduced by this technique; I mean the Fréon artists Thierry van Hasselt and Vincent Fortemps, mainly). Parts of La storia dell’Orso were also animated.

The dog is detached from the background in order to be animated. The trees are constant vertical and horizontal visual barriers.

Stefano Ricci’s drawing style is materic and sensual, but, at the same time, creates a distance that reminds of a strangeness (the feeling that something is not quite right) akin to mute cinema. Not showing the characters’ faces – darkening them – also helps the estrangement.

As I put it above, the humanized animals could be a reference to fables… It’s not exactly what happens here though. Stefano Ricci’s inspiration came from Shamanic culture. Since he admired Heinz Meinhardt’s work he chose him to be the story’s shaman linking the human and the animal world.

Being the original habitat of the grizzly bear, the forest is now humanized: the landscape is punctuated by roads, railroads, houses. Created by a well intentioned human program the bear is not allowed to show its true nature. The humans in the story also mirror the absurd feeling of “not belonging” symbolized by the bear: either because they are being chased (Enrico and Sirio) or because they have to adapt to a completely different set of political circumstances (Manfred when the GDR was united with the West) or because of losing territorial references (Stefano). As Michel Foucault put it (in Le courage de la verité – the courage of truth, 244):

It was by distinguishing himself from animality that the human being affirmed and manifested his humanity. Animality was always a point of repulsion in this constitution of man as a human being endowed with reason.

Stefano Ricci tells us that we may very well substitute “animality” with “being on the wrong side of a war or a revolution,” “belonging to a minority,” “being an immigrant,” you name it… We construct ourselves by not being them… And that’s the root of violence…

The hunter and his spider web.

![Felipe Hernandez Cava (w), Federico del Barrio (a), Lope de Aguirre, La conjura [Lope de Aguirre, the conspiracy], Ikusager, 1993.](https://www.hoodedutilitarian.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/Aguirre-227x300.jpg)

![Stefano Ricci, La storia dell'Orso [the bear's story], Quodlibet, 2014.](https://www.hoodedutilitarian.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/Orso-1-269x300.jpg)