Like most nerds, I communicate primarily in quotes from The Simpsons, but I’m old enough that Bloom County makes it into the rotation from time to time. Nary a San Diego Comic-Con can pass, for example, without a Superman comic or “My Little Pony” display triggering me to say to my husband, “The Truth, Steve, is that ‘Knight Rider’ is actually a children’s program.” (The correct response: “Can’t be! Can’t *@#!* be!!”)

When Bloom County debuted, it was criticized, often rightly so, for lifting from Garry Trudeau’s Doonesbury. Breathed’s loose, doodle-y early style was a slightly more polished version of Trudeau’s; he later developed into one of the most skilled illustrators on the comics page, more reminiscent of Chuck Jones than any newspaper cartoonist, but that would come later. Both cartoonists used an eclectic cast of slice-of-Americana characters to discuss current events. And both were unusually political for the comic strips of the era, which mostly stuck to safe sitcom material. Early on, Trudeau’s periodic hiatuses from Doonesbury allowed Breathed to replace him in some newspapers.

But in retrospect, Bloom County came from a fundamentally different perspective. Trudeau emerged from the 1970s late-counterculture tradition of National Lampoon and Saturday Night Live: erudite young left-wingers, trained on Ivy League humor magazines, out to smash the system with subversive comedy as a vehicle for progressive politics. Breathed’s strip anticipated the next generation, the style that would replace Lampoon-ing: media-saturated, self-referential, political only to the degree that politics is part of pop culture, as surreal and anarchic as a two-in-the-morning flip up the TV dial. The humor of Bloom County is the humor of The Simpsons and all that came after.

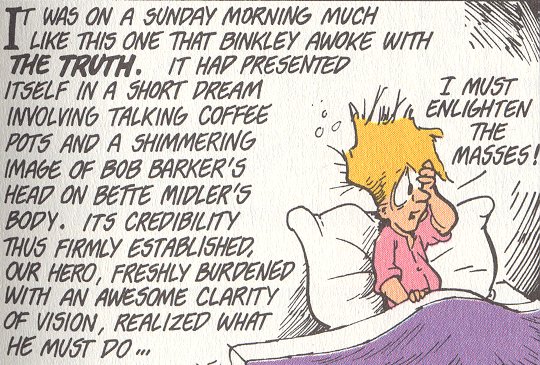

In its original context, the “Knight Rider” line is spoken by Binkley, the only Bloom County character to outpace Opus in gormless naïveté, after mysteriously awakening with a revelation of The Truth in all matters. The other knowledge Binkley shares: the Monkees didn’t play their own instruments, Opus looks more like a puffin than a penguin, and Reagan will never fulfill his promise to share Star Wars missile defense secrets with the USSR. That all of these revelations are presented as equal in importance sums up the difference between Bloom County and Doonesbury.

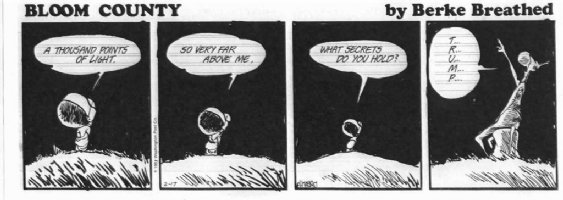

And that was life in America in the 1980s. The political became the personal, then it became the trivial. Colors were bright, patterns disorienting, everything expensive and hideous. The president was a movie star, of course, but more to the point it seemed reasonable for the president to be a movie star, to be just a guy hired to play The President. Billions of lives depended on a missile defense system named after the movie franchise that had just introduced Ewoks. We couldn’t handle the truth about the government or our souls, but neither could we handle the truth about David Hasselhoff. In Bloom County, Bill the Cat, the strip’s Garfield-parodying symbol of half-assed commercialism, has two recurring careers: rock star and presidential candidate. The careers are close to interchangeable and often inspire near-identical storylines. In the final years of the strip, Bill switches brains with Donald Trump, the human embodiment of the peculiar mishmash of money, politics, celebrity, and tackiness that could be said to define the decade.

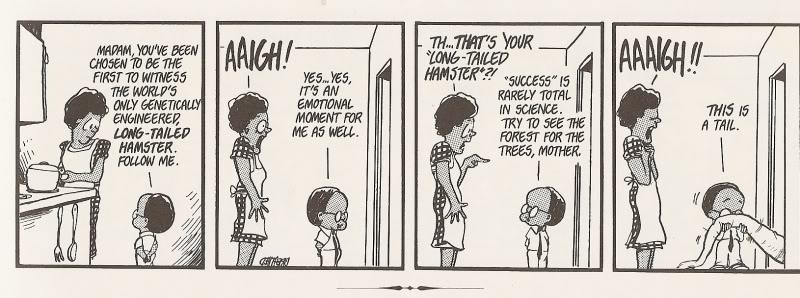

Many of the most successful Bloom County strips make a social observation without making a social statement. When the characters go hunting for the endangered liberal by baiting a trap with the Village Voice (“Just let me read the Feiffer cartoon!”), it’s very funny, but it doesn’t express any particular viewpoint about liberals or conservatives or American political debate. (Which is not to say that the artist’s personal views don’t sometimes come through; Breathed seems consistently uncomfortable with women and feminism, for instance.) One of the most famous Bloom County storylines begins with boy genius Oliver responding to South African apartheid by inventing a “pigmentizer” that turns white people black. An earlier generation of political humorists would have built this into a moralistic civil-rights fantasy, or followed the premise to disturbing and challenging places. A story that starts with apartheid has the potential to get dark. Instead, the gang gets lost at sea on the way to South Africa, leading to Opus eventually returning to Bloom County with amnesia, which is ultimately cured by news of Diane Sawyer’s wedding. Race relations, soap opera parodies, celebrity gossip: they’re all potential comedy material. Bloom County’s central innovation was to reject the old-fashioned idea that they should be different kinds of comedy.

The Simpsons played the same tune, ten years later, when it responded to Bush Sr.’s criticisms of the show’s crassness with “Two Bad Neighbors,” an episode portraying George and Barbara Bush as George and Martha Wilson from the 1950s Dennis the Menace TV show. In the DVD commentary for the episode, writers Bill Oakley and Ken Keeler comment that the older writers on staff were frustrated by the episode; they wanted a show about the President to be a sharp-edged political satire, not a pop-cult parody where the basic joke is “George Bush is old.” But the younger writers didn’t want to do satire. And George Bush was old.

To some degree Bloom County, which ran from 1980 to 1989 precisely, is of its time. In sheer volume of cultural detritus invoked, it certainly stands in stark contrast to the other great 1980s comic strip, Calvin and Hobbes, which strove for a sense of children’s-book timelessness. (My friend Jason Thompson once commented that he always found himself waiting for Calvin to pick up a video game controller.) Yet Donald Trump is still with us, all these years later, and so is David Hasselhoff, and so is the Bloom County sense of humor, the comedy that comes from collapsing every cultural signifier to a single level of blind, bland confusion and romping through the ruins.

Only occasionally does Bloom County take a coherent political or social stand, most notably in its extended attack on animal testing. More often, it adopts a “both sides are just as bad” attitude, or simply seems baffled by all the fracas. When Breathed abandons his post-counterculture cynicism and reaches for a sweet and gentle note, he usually does so by having the characters abandon their pop-culture wasteland entirely for a trip to the swimming hole or the dandelion patch. In Bloom County, there’s no salvation in political action or cultural revolution; the only hope is to drop out of our oversaturated civilization and go looking for reality. And that, maybe, is the final truth.

_____

The entire Bloom County roundtable is here.