This piece first ran on Splice Today

__________

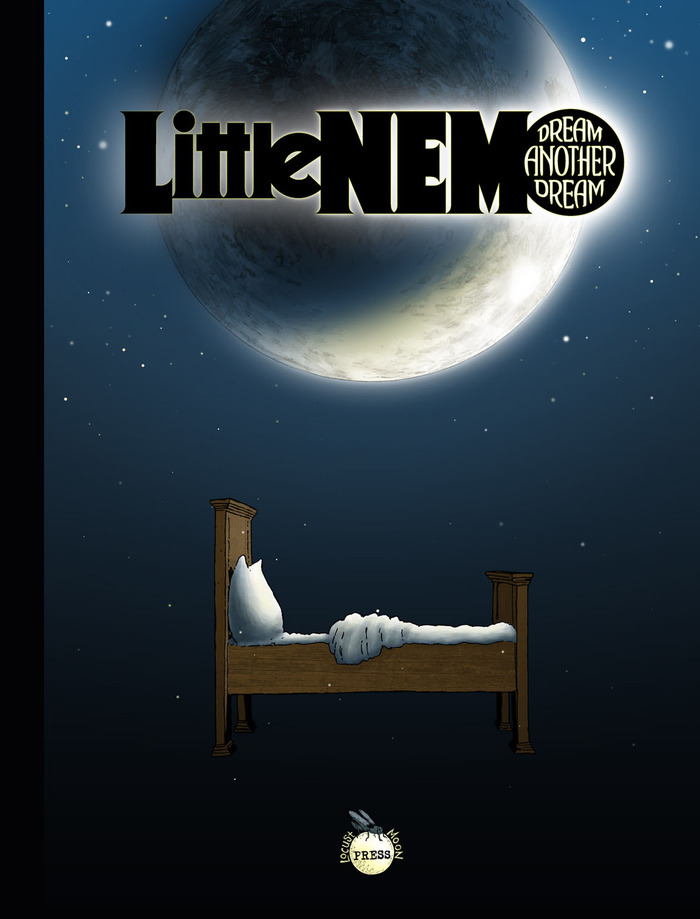

“Now that most of Winsor’s work is public domain he can be imitated by lesser artists with a fraction of his skill and vision,” artist Fil Barlow quips in his contribution to the kickstarter-funded Winsor McCay tribute anthology Little Nemo: Dream Another Dream. The volume — paying homage to the famous newspaper comic in which Nemo falls asleep each night, dreams fantastical dreams, and then falls out of bed into waking in the last panel, —features an embarrassment of talent. Starting with Gerhard’s magnificent Escher-like frontispiece, the oversize volume, which ran a successful kickstarter campaign, includes ravishing full page works by Craig Thompson, Bill Sienkiewicz, P. Craig Russell, Jill Thompson, Carla Speed McNeil, and just about everyone else you can think of in the world of comics.

And yet, despite the skill on display, Barlow’s snark still has bite. If there’s one person in the world of illustration who’s inimitable, that person would be Winsor McCay, with his walking beds and giant dragons and monstrous geese, his inexhaustible drawing facility and equally inexhaustible imagination. McCay already drew the perfect Little Nemo. Why does anyone else need to bother?

Barlow suggests that others are bothering, or are able to bother, because McCay’s work is out of copyright. Public domain has left McCay’s corpus defenseless before the onslaught of rabid artistic poachers.

It’s certainly true that an independent publication on the scale of Dream Another Dream wouldn’t have been feasible for copyrighted work; you can’t just start a Mickey Mouse Kickstarter project without Disney’s say so and expect that to be okay. But just because a comic remains in copyright is hardly a guarantor that the original artistic vision will be left politely alone. Copyrighted characters are regularly reinterpreted across multiple media by artists who have little interest in, and often seemingly little knowledge of, the original creations. As just one example, the hunky salt-of-the-earth Kryptonian-battling Superman in Man of Steel doesn’t have a whole lot to do — visually, conceptually, or ideologically — with the quasi-socialist high-jumping basher of corrupt mine-owners that Siegel and Shuster invented way back there in the Great Depression. The forthcoming Dr. Strange movie will almost certainly abandon Steve Ditko’s visual style and Stan Lee’s overcarbonated prose for something blander and more conventional.

Being public domain doesn’t make Little Nemo uniquely vulnerable, then. On the contrary, being public domain seems to afford him some measure of protection. When you’re owned by a large conglomerate, there’s no telling what sort of sordid nonsense will happen to you under the auspices of “official” continuity — a villainous thug may turn into a dashing anti-hero, a warrior woman can be changed into an amnesiac sex doll. Why not, if it’s good for business?

Public domain, though, seems to at least potentially change the incentives. Nobody owns Nemo. He doesn’t belong to a corporation; he belongs to everyone. And since he belongs to them, the artists in this anthology treat him as if he’s in their care.

Not that all the cartoons here are necessarily reverent. Alexis Ziritt’s psychedelic Jack Kirby meets Day of the Dead space skull vomit is about as far as you could get from McCay’s preternaturally neat art nouveau style, while R. Sikoryak’s Freud/Little Nemo team-up introduces the kind of layered dream interpretation that McCay’s dazzling surfaces deliberately, and even ostentatiously, avoided. Even when artists in the volume deliberately subvert McCay, though, it’s McCay they’re deliberately subverting. It’s his original that they’re playing with, or riffing off of, or questioning. Sometimes it’s just an affectionate nod to his themes, as in Carla Speed McNeil’s adorable fantasy of a giant cat. Sometimes it’s a clever stylistic nod, as in Moritat’s use of imagery from Asian prints, neatly suggesting some of the sources (perhaps once or twice removed) for McCay’s own visuals.

And in many cases, it’s a tribute to the amazing way McCay put together a page. Paolo Rivera’s tour de force juxtaposition of the song “Row, Row, Row Your Boat” with a self-referential meta-adventure narrative, for example, seems only tangentially related to Little Nemo’s art; the visuals seem to owe as much to Hergé as McCay, and the verbal economy certainly isn’t inspired by McCay’s meandering repetitive prolixity. And yet, McCay’s hand is there, in the way that the page is seen so strongly as a spatial and temporal whole. McCay wouldn’t speed up time, or have his narrative loop back around, the way that Rivera does, but Rivera is able to do it because of the ideas, and the tool-kit, McCay gave him.

Admittedly, some piece in the book don’t gel. Peter Bagge’s wise-cracking, clunky cartooning style is a particularly poor fit for McCay’s elegant wonder; Dave Bullock and Josh O’Neill’s use of received fantasy adventure tropes seems like a waste next to McCay’s much less hidebound flights of fancy. But even the failures are talking to the original, not stealing from it, or ignoring it in the name of some larger cinema audience determined by focus group. We tend to see copyright as a way to protect intellectual property from abuse or misuse, but this tribute volume suggests that it may have the opposite effect. A dream isn’t meant to sit forlornly by itself in a bank vault with a bunch of lawyers; it’s meant to get out and inspire people. The more artists take from McCay, the bigger McCay gets. The more public Nemo becomes, the bigger the domain of his dream.