I’m blogging my way through all the stories in A Drunken Dream, the collection of Moto Hagio’s stories out from Fantagraphics. You can see all posts about this collection here.

_______________________________________

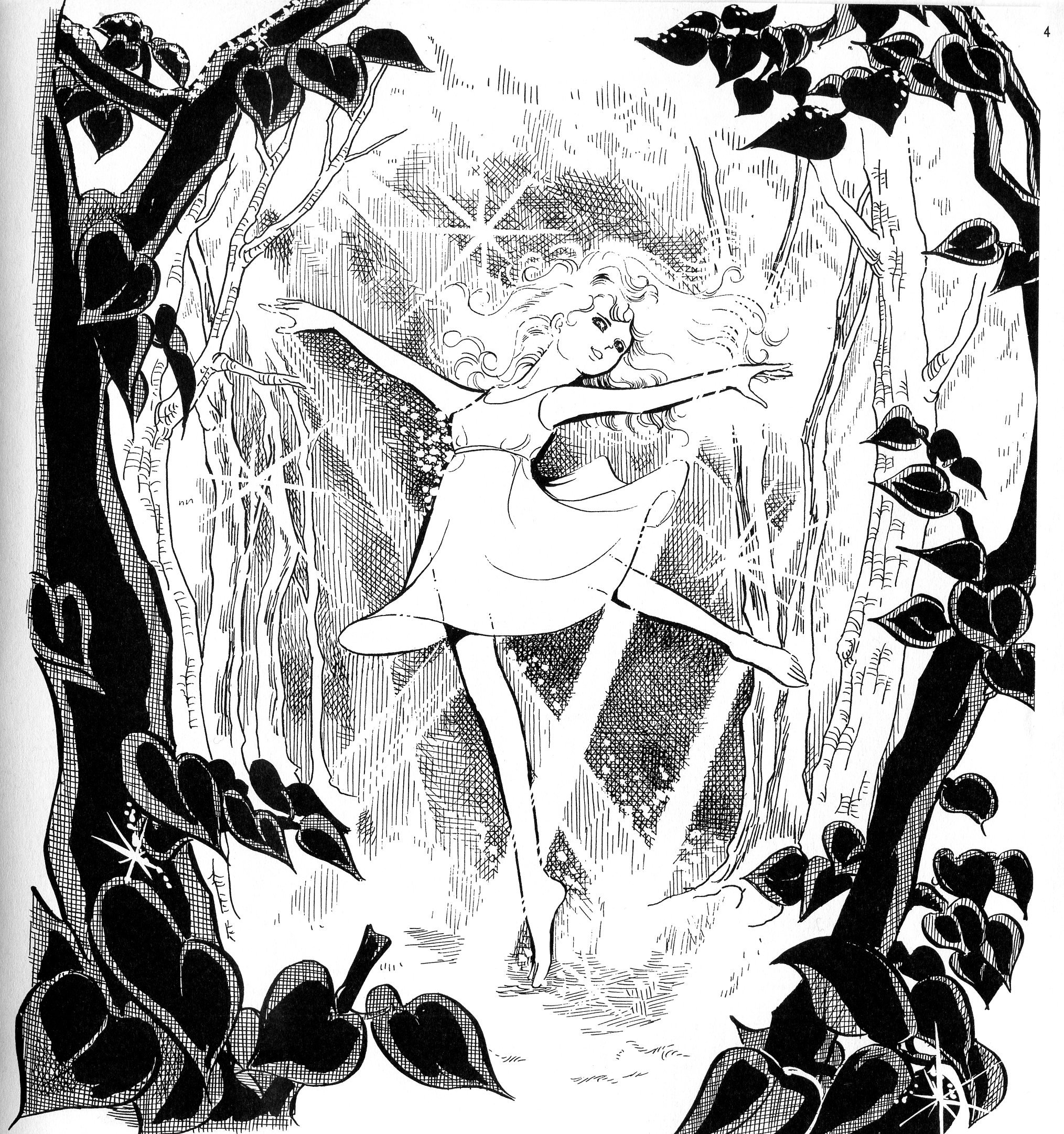

Moto Hagio’s “Hanshin: Half-God” is about Yudy and Yucy, conjoined twins. Yudy, who tells the story, is ugly, shrivelled, articulate, and competent; her twin sister, Yucy, is a beautiful, mute parasite, who sucks away both Yudy’s nutrients and the affection of parents, relatives, and passersby. Yudy has to help Yucy walk and bathe and perform even the simplest tasks; in return, the simple Yucy gives Yudy frequent fevers and bothers her while she tries to study genetics. Eventually, doctors decide that the twins will die if they are not separated; the only choice is to cut loose Yucy, who will die, allowing Yudy to live. Separated from her twin, Yudy grows into a normal young woman. The end.

Sort of. If that was the story, it would be a fairly straightforward, even banal feminist parable about casting off gender expectations in order to find your true self. Yucy, the delicate, helpless, beloved beauty, has to be destroyed before Yudy can grow up into a competent, independent woman. QED.

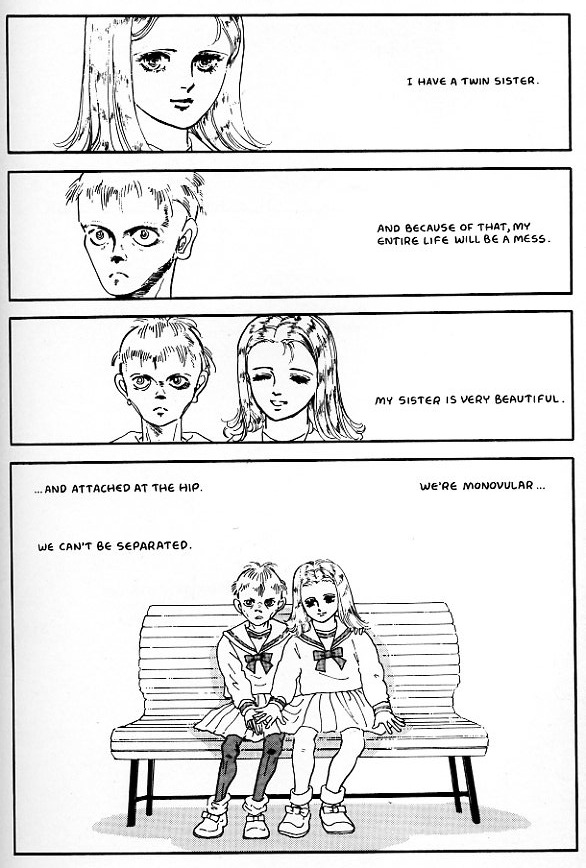

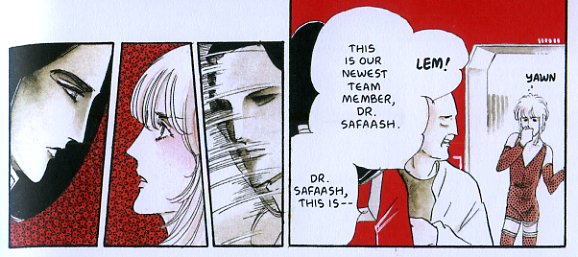

In this reading, Yudy and Yucy are different aspects of the same person…and there’s plenty of evidence for that in the art. For instance:

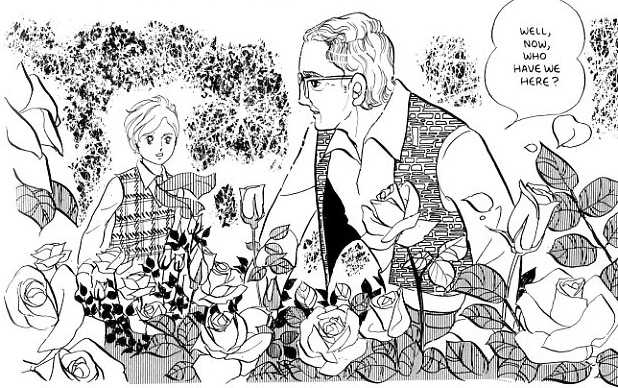

The first panel show Yucy off to the left against a blank background; then the second shows Yudy in the same position. In the third we see the two together…and only in the final panel on the page do we learn that they’re “attached at the hip.” The surprise reveal is, though, clearly rigged. If the two are attached, we shouldn’t be able to see them without each other. Particularly in the second panel, Yudy is placed so that we should see Yucy to her right — but all we see is blank space. The implication is that Yucy doesn’t exist except as metaphor…or perhaps, that Yudy doesn’t, since it’s Yucy we see first.

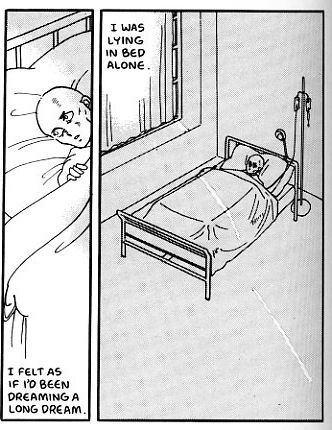

Again, just after the sisters have been separated, Hagio put in a tell.

“I felt as if I’d been dreaming a long dream.” The twin is just a fantasy; only when she is separated is Yudy living real life for the first time. The perfect girl she is supposed to be doesn’t exist.

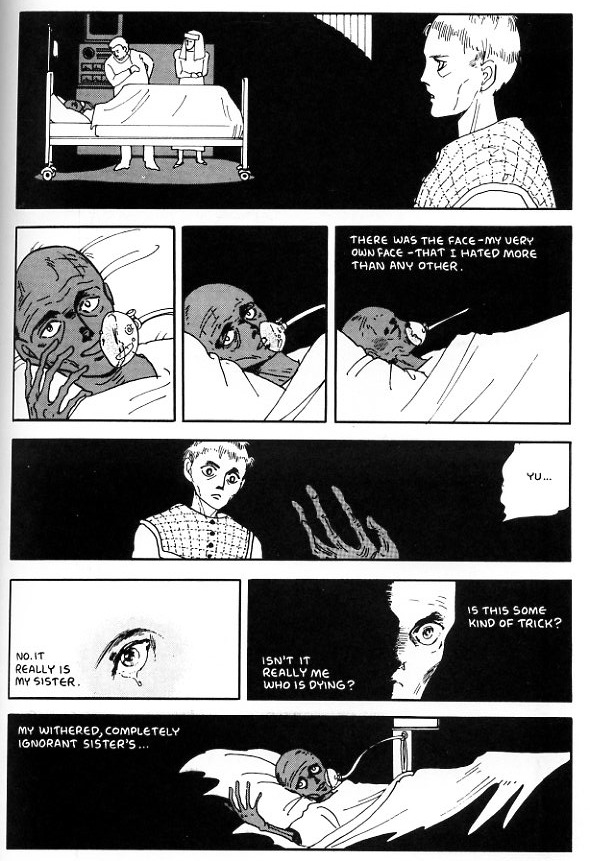

Except that she sort of does. Yucy doesn’t die immediately after being separated; instead she slowly wastes away. Yudy goes to visit her one last time, and is startled to see that her sister has turned into her own mirror image.

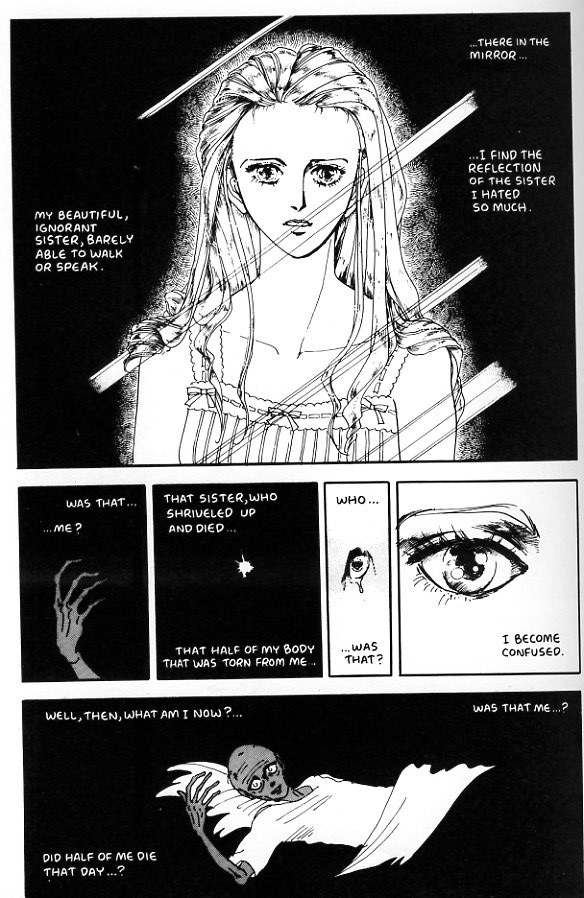

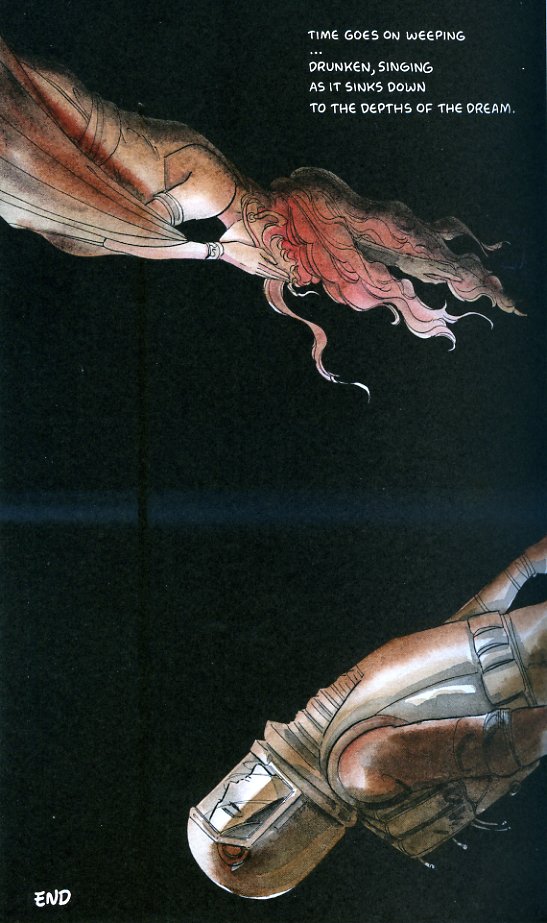

You could see this as still being about the escape from gender stereotypes — “Isn’t it really me who is dying? No it really is my sister.” Again, this could be a statement that the gender-normative self is not Yudy; that she has escaped other’s expectations. But the affect is off. Instead of joy or release, Yudy feels disorientation and grief. The self she has left behind is “really” a self; indeed, it now seems more like the real her than the her that has survived. As time goes on and she becomes healthier and healthier, Yudy begins to look like the sister who died, until finally she wonders which of them was killed:

The story is no longer about casting off an oppressive femininity. Instead, it’s about…what? Betraying the self perhaps…but how exactly? Has Yudy betrayed herself by turning into the femininity she thought she was rejecting? Or was the rejection of that femininity — which also encompasses childlike innocence — itself a betrayal? Or is it the loss of her pain which is a betrayal; leaving behind the helpless, shrivelled, wretched self to become a competent adult? If so, the bind seems double and unescapable; to grow up, one has to abandon one’s attractive weakness, but doing so is always a betrayal of that weakness. The child is not the adult, even moreso because the child is still there in your face. Or, perhaps, the conflict is not internal at all. Perhaps the bond that holds together Yudi and Yuci isn’t sisterhood or self, but love, and it’s the abandonment of that love for femininity which causes Yudi to both become more feminine…and to be haunted by the conviction that she has lost herself.

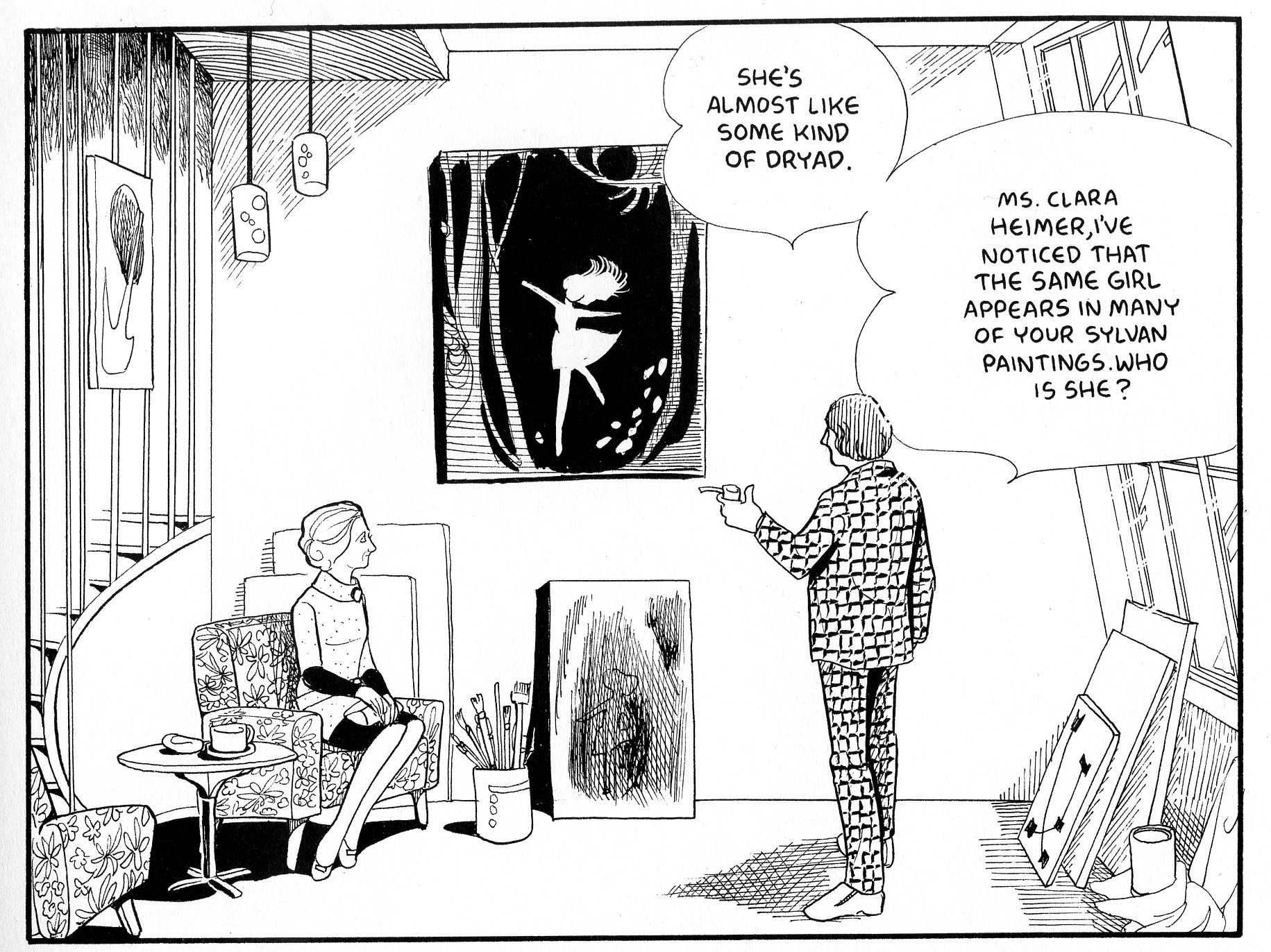

There isn’t any one “solution” to the story, of course. This is emphasized by the fact that there isn’t one Yudy, or even two, but many. In a recent post about doubles in comics, Caroline Small suggested that comics can do doubling in a way that is less “labored” than prose. I was skeptical about this — but Hagio’s story may have changed my mind. Because in “Hanshin,” the metaphorical uncertainty around Yudy and Yuci becomes an actual, concrete ambiguity. That is, when Yudy sees Yuci lying on the hospital bed, and wonders, “Is this me or is this my sister?”, the narrative insistence on ambiguous doubling actually obscures the concrete doubling — Hagio is, in this sequence, drawing the same person twice — or more accurately, six times.

Yudi and Yuci in Hanshin are just names, assigned as Hagio wishes to different iterations of the same body. In her confusion about who she is, Yudi is more, not less, aware of reality — she senses the arbitrariness of Hagio’s choices, the way that names and identities are linked, not as absolutes, but through arbitrary decisions.

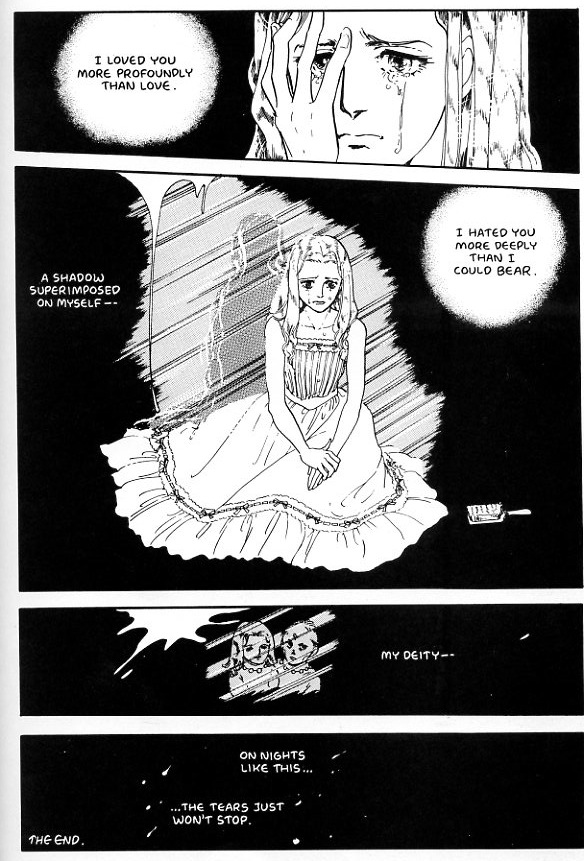

We “know” that is Yudi, but if Hagio changes the words, it could just as easily be Yuci who grew up. Which raises the question…who is talking here? Is that Yudi? Yuki? Or is it Hagio herself? “I loved you more profoundly than love. I hated you more deeply than I could bear. A shadow superimposed on myself….My deity —” Whose shadow? Whose deity? If one is drawn as two and two as one, who is doing the drawing? The same person who did the killing? Is the deity the one who is there or the one who is not, and how can you tell the difference? To create your soul is to split your soul; a god who has always already left half of herself behind.