For this column, I’d like to return to the subject of comics criticism. A while back, HU hosted a Popeye roundtable, which raised some interesting general questions, but seemed to stop from lack of enthusiasm before it went very far. Not being in a position to contribute at the time, I would like to resurrect it for the purpose of raising a number of issues pertaining to how we talk about comics and art.

Noah in his ambiguous essay on E. C. Segar’s strip expresses frustration at what he perceives to be its shallowness:

Though I enjoyed the energy of the drawing, and the Sea Hag and Goon provided some evocatively creepy moments early on, the limited range of the humor, and its empty-headedness, quickly becomes numbing. Wimpy is lazy, Wimpy eats a lot, Popeye is noble, defends the underdog, and always wins.

Robert, in his piece, which references a series of earlier, excellent reviews on his own site, concludes that the strip is “largely of historical interest”, writing:

The challenge I gave the work was for it to transcend that description. It occasionally did; there were flashes of satirical and absurdist genius every now and then. “The One-Way Bank” storyline from Volume II and the finale of “The Eighth Sea” storyline from Volume III stood out, and I was especially taken with Volume II’s “The Nazilia-Tonsylania War” — its treatment of state and military folly ranks with Dr. Strangelove (almost) and Duck Soup. (No pun was intended with the name “Nazilia,” by the way.) However, Segar was generally far more enamored with farce and slapstick for their own sake than he was with satire. That greatly limits the appeal of his work, at least for this adult reader. Farce and slapstick that don’t connect with anything deeper are best in small doses; they tend to wear out their welcome fairly quickly.

So the strip is less than great because it is simplistically conceived and primarily concerns itself with slapstick and farce, only rarely ‘transcending’ these. For Robert, this happens when it becomes satirical, because that somehow connects ‘deeper’ than mere laffs.

This seems to me a holdover from modernist conceptions of aesthetic value that privilege the framework provided by the ‘high’ arts. Robert even spells out this bias:

No reasonable person would consider it on the level of Faulkner, Kandinsky, or Jean Renoir’s work, but it looks right at home when viewed alongside the efforts of Mae West, W.C. Fields, and the Marx Brothers. I have nothing against the popular-entertainment standard for determining “good” comics, by the way. If a comic entertains people, it’s doing its job. And if it’s entertaining people to the extent that it becomes a pop-culture phenomenon, which Segar’s Popeye certainly did, then it’s doing its job terrifically well.

…But it still isn’t as great as Faulkner, Kandinsky or Renoir. Invoking the consummate elitist Harold Bloom’s definition of the canon as what should be taught in our schools, Robert judges Popeye out. But why? He has himself conceded that it gripped more than one generation of readers and became a pop-culture phenomenon. Isn’t that worth teaching in schools? And what about those great humorists cited? Irrelevant to the understanding of our culture?

My intention here is not to claim that Popeye – or Thimble Theater if we want to be correct – is the equal of the best high art had to offer at its time (conversely I’m not saying that it ain’t either). What I am saying is that it will necessarily look impoverished when judged in the framework of high culture, and that I find such a yardstick unhelpful in assessing its qualities — qualities that clearly resonated widely and persistently. Although we have now for several decades described our times as postmodern, with everything that entails, the elitist legacy of modernity is amazingly hard to shake.

Noah recognizes this, essentially framing his dismissal of the strip as personal preference. He compares with another low-culture medium, which has received even less high-culture acclaim: television, concluding that,

…what is and isn’t considered art is really arbitrary. Comics critics have spent a lot of energy for the past decades trying to get comics accepted as high art. They’ve had definite (if not unqualified) success, and now even frankly pulp, unpretentious works like Popeye can be put up in galleries, given lavish reissues, and hailed as canonical examples of the form.

I would guess that someone like Noah, who spends a fair amount of energy as a critic acclaiming the qualities of some of the most commercial iterations of contemporary pop music, would be unsatisfied with the kind of high-culture point of view brought to bear on comics by some of its more assiduous critics at this current, mercurial juncture in their history.

Having long regarded hip hop as one of the most inspiring cultural manifestations of the last 30 years, I sympathize. It has been interesting to watch its fortuna critica in the cultural establishment as it has evolved: regarded initially as a fad, its staying power has come to be recognized and it is now classified as a legitimate musical genre, but it still isn’t considered an art form on the level of, say, rock music. “Gangsta Gangsta” by N.W.A simply doesn’t cut it when measured by the yardstick of “Like a Rolling Stone”, but it is undeniably a hugely resonant piece of work, every bit as influential on the generation from which it sprang.

Similarly, at the time of Thimble Theater, surely ‘no reasonable person’ would consider something like ragtime or jazz on the level of opera. Yet, today, these forms and their progeny are regarded as entirely respectable art forms, capable of greatness akin to that achieved in classical music. Music unites us in ways that other art forms don’t, and we seem to be more receptive to “shallow” qualities there than we do in literature, fine art, or even comics. Perhaps this is not so surprising, since music generally is less cerebral than those forms, making us appreciate — and intellectualize — our emotional and visceral responses to a higher degree.

And actually at least one perfectly reasonable person did consider ragtime and jazz, and with them a whole range of other popular forms such as vaudeville, the movies, and yes, comics, on the level of high culture. A cultural critic and New York correspondent of T. S. Eliot’s Criterion, his name was Gilbert Seldes (1873-1970). In his precocious defense of popular culture, The Seven Lively Arts (1924), he wrote:

If you can bring into focus, simultaneously, a good revue and a production of grand opera at the Metropolitan Opera House, the superiority of the lesser art is striking. Like the revue, grand opera is composed of elements drawn from many sources; like the revue, success depends on the fusion of these elements into a new unit, through the highest skill in production. And this sort of perfection the Metropolitan not only never achieves — it is actually absolved in advance from the necessity of attempting it. I am aware that it has the highest-paid singers, the best orchestra, some of the best conductors, dancers and stage hands, and the worst scenery in the world, in addition to an exceptionally astute impresario; but the production of these elements is so haphazard and clumsy that if any revue-producer hit as low a level in his work, he would be stoned off Broadway. Yet the Metropolitan is considered a great institution and complacently permitted to run at a loss, because its material is ART. (pp. 132-133)

Lest he be dismissed offhand as the kind of contrarian philistine such statements might evoke in us today, I hasten to supply the following; during a visit to Picasso’s studio in Paris, he was shown a fresh canvas by the master, which prompted in him a synthesis:

I shall make no effort to describe that painting. It isn’t even important to know that I am right in my judgement. The significant and overwhelming thing to me was that I held the work a masterpiece and knew it to be contemporary. It is a pleasure to come upon an accredited masterpiece which preserve its authority, to mount the stairs and see the Winged Victory and know that it is good. But to have the same conviction about something finished a month ago, contemporaneous in every aspect, yet associated with the great tradition of painting, with the indescribable thing we think of as the high seriousness of art and with a relevance not only to our life, but to life itself — that is a different thing entirely. For of course the first effect — after one had gone away and begun to be aware of effects — was to make one wonder whether it is worth thinking or writing or feeling about anything else. Whether, since the great arts are so capable of being practised today, it isn’t sheer perversity to be satisfied with less. Whether praise of the minor arts isn’t, at bottom, treachery to the great. I had always believed that there exists no such hostility between the two divisions of the arts which are honest — that the real opposition is between them, allied, and the polished fake. (pp. 345-346)

I think we could do worse than take a cue from Seldes’ notion of the ‘lively arts’ in our current reassessment of comics as cultural phenomena and art. About the comic strip:

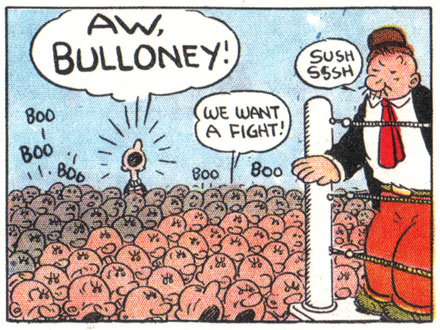

Of all the lively arts the Comic Strip is the most despised, and with the exception of the movies it is the most popular. Some twenty million people follow with interest, curiosity, and amusement the daily fortunes of five or ten heroes of the comic strip, and that they do this is considered by all those who have any pretentions to taste and culture as a symptom of crass vulgarity, of dullness, and, for all I know, of defeated and inhibited lives. I need hardly add that those who feel so about the comic strip only infrequently regard the object of their distaste.

Certainly there is a great deal of monotonous stupidity in the comic strip, a cheap jocosity, a life-of-the-party humour which is extraordinarily dreary. There is also a quantity of bad drawing and the intellectual level, if that matters, is sometimes not high. Yet we are not actually a dull people; we take our fun where we find it, and we have an exceptional capacity for liking the things which show us off in ridiculous postures — a counterpart to our inveterate passion for seeing ourselves in stained-glass attitudes. (p. 213)

Seldes doesn’t mention Thimble Theater, and couldn’t have known Popeye (on account of he hadn’t been born’d yet), but he regarded highly its neighbor in the New York World, Krazy Kat, whose creator George Herriman he considered one of the two genuine artistic geniuses in America at the time (the other was Charles Chaplin). In his famous essay on that strip, he wrote:

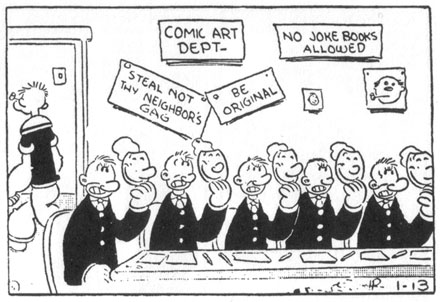

With those who hold that a comic strip cannot be a work of art I shall not traffic. The qualities of Krazy Kat are irony and fantasy — exactly the same, it would appear, as distinguish The Revolt of the Angels; it is wholly beside the point to indicate a preference for the work of Anatole France, which is in the great line, in the major arts. It happens that in America iron and fantasy are practised in the major arts by only one or two men, producing high-class trash; and Mr Herriman, working in a despised medium, without an atom of pretentiousness, is day after day producing something essentially fine. (p. 231)

Granted, Krazy Kat has received greater high-culture recognition than any other strip of its day, and seems more effortlessly to accommodate a fine arts perspective, but I don’t see why one couldn’t formulate something along similar lines for Thimble Theater. Noah suggests that one might compare the strip with the cinema of Buster Keaton, which strikes me as particularly instructive:

Keaton’s work rightly occupies an important place in the cinematic canon, despite it being similarly resistant to the kind of interpretative framework that eschews slapstick. As the New Wave filmmakers recognized, however, his auteurial presence is acutely felt throughout his work, and it gives us a highly original, fatalistic and uncannily comic conception of depersonalized action in a world of strange, fickle serendipity.

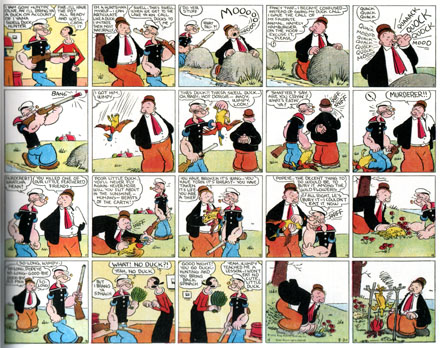

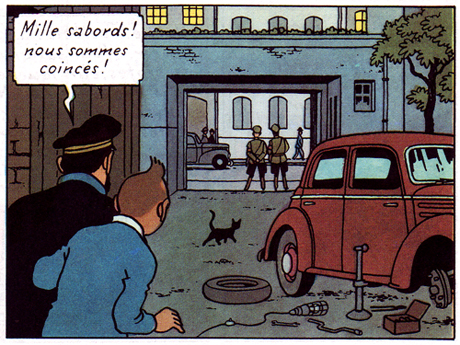

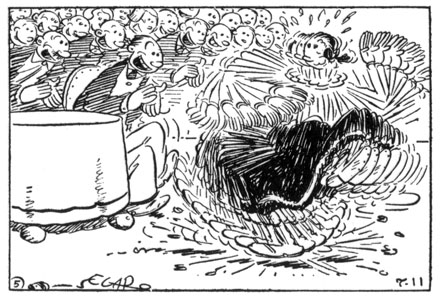

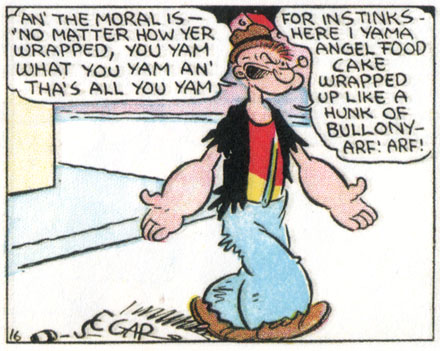

Now, let’s look at fairly typical, self-contained Sunday page from Thimble Theater (sep. 30th, 1934):

On the surface, it delivers a straightforward gag pitting, as is so often the case, Popeye’s morality against Wimpy’s lack of same. But Segar is anything but a utilitarian gang man; he proceeds like a cartoon behaviorist, generously packing in as much character detail and humorous instance to create a highly seasoned repast, all the while unfolding a strongly intuited moral ethos.

Watch his unaffectedly plump line and vernacular wit unfold across the page: Wimpy insinuating himself into the frame and the duck hunt, bodily/verbally; his mention of his favorite animal, “hamburger on the hoof”; the manner in which he splays his three surplus fingers while pressing his nose to quack (and, inevitably, to hamburger moo); his poker face registering the hit, turning to sniff; the derision on his face against Popeye’s soon-to-vanish irascible scowl; the silent burial bookending Popeye’s contrition, Wimpy empathetically yet efficiently settling the mound; the exchange: “WHAT! NO DUCK?!” — “Yeah, no duck”; the unchanged expression on Wimpy’s face as he kneels caninely to exhume the duck with speed, his coattails waving; it remains unchanged as he sits at the end, counter to the left-right flow, roasting the kill.

Clear in presentation, yet richly studied, this sequence is a perfect summation of the profane reality of Thimble Theater. A true comedic hero, Popeye is pugnaciously selfless in a world governed by selfishness. He always restores order around him (often, disturbingly, by violence), but is simultaneously given enough of a tragic edge — his morality is rarely reciprocated — to keep us involved. As with Keaton, there’s a fatalistic undertone to his and, by its frequent extension to the rest of the cast, the strip’s indomitable catchphrase: “I yam what I yam, an’ that’s all I yam!” It’s trenchantly inspirational and it is great fun, so why can’t it be great art?

Part of the answer, if one compares with cinema, is that it has taken comics much longer to expand its field beyond a fairly restricted set of idioms and genres, all of which are candidly low culture. It hasn’t had its James Agee, though people like Donald Phelps, R. Fiore and Art Spiegelman have done their best in recent decades; they haven’t had their Raymond Rohauer and have only recently begun experiencing comprehensive restoration and republication, and they haven’t had their new wave until now.

Which brings us to the matter at hand: this is a time of redefinition for comics, which is not only manifest in contemporary cartooning, but naturally extends back to encompass its history. Neglected by critics and historians, and forgotten even by most cartoonists, the classics now demand our attention for what they teach us about their time and the evolution of the form, but ultimately also as works of art. Though it is surely healthy to assess comics in the expanded field of cultural production being opened up as distinctions between high and low are collapsing, to not cut them any exceptionalist slack, it would seem ill advised to judge them according to antiquated systems of hierarchical exclusion.

PS — Because Noah mentioned them as part of his high-low concordances, I can’t help bringing in the Coen brothers here. While it is correct that they are becoming canonized as directors, it is remarkable that their best loved, and arguably best though not most critically acclaimed film, The Big Lebowski, is so unabashedly shallow. It totally fails the modernist test as a work of art, and yet there it is, and it’s glorious.

Squint, imagine some more punching, and it might almost play at the Thimble.