A week or so back, I posted a response to a post by Jeet Heer which prompted a strenuous objection from Gary Groth. In the course of responding to Gary, I said this:

I was replying to the structure of [Jeet’s] argument and to his examples, not to his actual argument per se.

There seemed to be some confusion about this, and some suggestion that more explanation would be helpful. So I’m going to give it a try. This is going to be somewhat ad hoc, and I suspect if I knew my linguistic theory better, I’d be able to (a) have better terms at my fingertips, and (b) present a better case. But you work with what you have.

Right; off we go.

Any work of art (defined quite broadly here) is going to create meaning in various ways. I’m going to divide those ways of creating meaning into two.

First, you have what I”m going to call “emphatic” meaning. I also thought of referring to this as utilitarian meaning or didactic meaning. This is the meaning that is purposeful or directed; it’s what the work of art is saying that it is about. In a novel, this might be plot; in a portrait, this might be the effort to represent the sitter. Intentions aren’t always easy to parse, but with that understood, emphatic meaning would in general be the obvious, intentional point of a piece.

Second, you have what I’m going to call “phatic” meaning. If you’re not familiar with the term “phatic,” Wikipedia is helpful as ever.

In linguistics, a phatic expression is one whose only function is to perform a social task, as opposed to conveying information. The term was coined by anthropologist Bronislaw Malinowski in the early 1900s.

For example, “you’re welcome” is not intended to convey the message that the hearer is welcome; it is a phatic response to being thanked, which in turn is a phatic whose function is to be polite in response to a gift.

Here, though, I’m using “phatic” not just to mean a word or phrase meant as a social placeholder, but rather any element in a work of art that isn’t directly pushing the emphatic meaning. The phatic here is the excessive, the superfluous, the additional. I think you could argue, in fact, that the phatic defines the aesthetic; it’s the additional meaning beyond the utilitarian, which creates ambiguity, frisson, beauty, and the other kinds of confusions and responses we think of when we think “art.”

These distinctions are somewhat arbitrary, and you could argue about whether a particular meaning is phatic or emphatic. And of course most critics (which is to say, most readers or viewers) don’t systematically separate out meanings in this way. But I think the terms and concepts can be useful in thinking about what we’re doing as critics or readers.

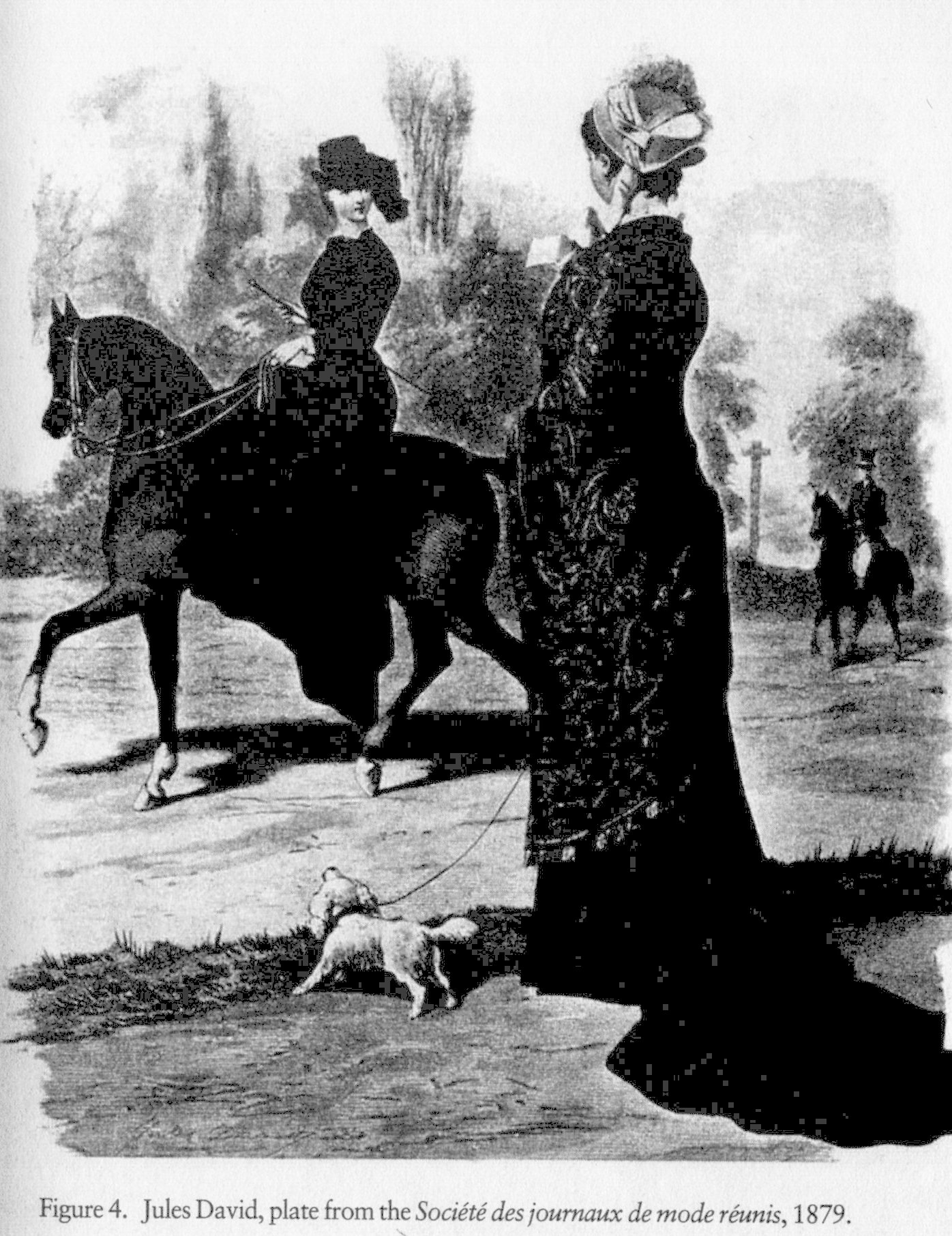

Okay, so let’s try some examples. Here’s a Victorian fashion plate, as shown in Sharon Marcus’ 2007 book Between Women: Friendships, Desire, and Marriage in Victorian England.

The emphatic meaning here is, obviously, “look at the pretty clothes.” (Though you lose some of the emphasis thanks to my not ideal scan; sorry about that.) The image is designed so that the viewer (presumably female) can look at the dresses on display. The dresses themselves, then, are the emphatic content. In some sense, you don’t need anything but the dresses. The dog, the horse, the guy in the background, even the women filling up the dresses are superfluous. They add charm or interest, but they’re not the emphatic point.

So if you wanted to talk about this picture looking at the emphatic meaning, you could critique the rendering of the dresses (are they accurate? are they pleasing?) and you could also pull back and talk about whether selling dresses like this is a worthwhile use of art (capitalism, Marxism, hackwork, what have you.)

However, there is also phatic content in the picture — that is, it isn’t just two dresses standing there. There is the dog, there’s the guy, there’s women filling the dresses out. Though the point is the dresses, those dresses have been placed in a scene — and we can think of that scene as excessive, or phatic.

Now, you could just say, “well, the scene isn’t the point — it’s phatic, and so it’s not worth getting into how it’s set up or why the artist made the choices he/she did.” That’s one possibility. But you can also take the phatic content as being as, or even more, important than the emphatic content. That is, the phatic content has meaning too; it’s excess, but it’s not empty excess.

So here’s Sharon Marcus, doing a critical reading based mostly on the phatic content of this image;

Fashion plates were images of women designed for female viewers, and that homoerotic structure of looking is intensified by the content and structure of the images themselves. Fashion plates almost never depicted women singly or coupled with men, but most often portrayed two women whose relationship is contained and undefined. An 1879 plate shows a woman on horseback staring intently at another woman whose back is to us and appears to return the rider’s gaze; a male figure in the background appears to look toward and reflect the viewer, who watches the two women as they inspect one another. The park setting and the physical distance between the two women code them as passing strangers, intensifying the erotic valence of their mutual scrutiny. The composition suggests that the two women are about to move toward one another….Fashion, often associated with a sexually charged inconstancy, becomes a respectable version of promiscuity for women, a form of female cruising, in which strangers who inspect each other in passing can establish an immediate intimacy because they participate in a common public culture whose medium is clothing. That collective intimacy extended to the fashion magazine itself, consumed by thousands of female readers separately but simultaneously.

A woman who looked at a Victorian fashion plate did not simply find her mirror image, for in that plate she saw not one woman, but two.

In a bravura move, Marcus takes the excessive phatic meaning (not one dress, but two women) and twists it back into the emphatic meaning (fashion as not just intended to sell dresses to women, but to sell the women in the dresses to each other.)

An analogous example in prose: Marcus in her book does an extended reading of Great Expectations. She talks a good deal about the plot…but she also pays a lot of attention to when Dickens does and does not describe Pip’s clothing. In one sense, the description of fashion is always superfluous to the plot; you don’t need to know what Pip is wearing to know what happens to him. But Marcus argues that the book is in large part about Pip’s effort to escape his social class, which is equated with his masculinity. That is, Pip is trying, in her reading, to become a woman, and the sign of this in the text is his relationship to his clothes. His finery, therefore, is a sign of his progress towards (or a failure to progress towards) his Great Expectations. The excess phatic meaning is not just excess silk and lace, but something which can be read as important in its own right.

Doing a reading that includes a discussion of phatic content isn’t at all controversial. On the contrary, the phatic content is the focus of a lot of the most creative criticism, precisely because it is less straightforward and often more open to interpretation.

But, at least among the folks I talk to in the comics blogosphere, there seems to be some resistance to thinking about phatic fripperies as central when it comes to critical prose. For me, on the other hand, it seems like a very natural thing to do. That’s what I did in my initial discussion of Jeet Heer’s post. In particular, when Jeet said this:

If we define criticism narrowly as analytical essays on an art form or particular works of art, then it’s true that criticism is a minority interest. But if we define criticism more broadly as any discussion of art or works of art, including conversations and the response of artists themselves to earlier art, then criticism is as unavoidable and essential as art itself. To be more concrete, some of the best comics criticism has come in the form of interviews done by artists like Gil Kane, Robert Crumb, Art Spiegelman, etc. As Joe Matt mentions elsewhere in the discussion, he turns to interviews in The Comics Journal before anything else. Without these interviews, our entire sense of comics would be very different.

I responded by saying this:

For Jeet, the ultimate justification for criticism seems to be that artists do it.

Gary in turn responded by saying this:

Jeet said nothing of the sort, seemingly or otherwise, in the paragraph you quote to support that assertion. His point, obviously, is that criticism takes place in interviews.

And Gary’s right; that is the most obvious point of Jeet’s statement. In the terms above, it’s the emphatic point. Jeet’s argument, the point he is getting at, is that there is criticism in interviews. Period.

But there’s more in the statement than just “There is criticism in interviews.” Jeet doesn’t just say, “There is criticism in interviews” (or,more fully, “There is criticism outside of analytic essays.”) He fleshes that argument out with other words, examples, and rhetorical flourishes. All of that excess is the phatic content. And if you look at how the argument is arranged, what you see is that Jeet states in general that there are many different kinds of criticism, and then clinches (or makes concrete) the worth or importance of those kinds of criticism not by attempting to explain why criticism is important or necessary in itself, but instead by making an appeal to authority.

This is why Gary is especially wrong when he says that “Jeet doesn’t let Matt off the hook”. Because if you look at the way the argument is structured, the final appeal to authority is to — Joe Matt. The argument is structured not in terms of, “Joe Matt said this dumb thing, and he’s wrong for this reason.” Rather, it’s set up as a tension between authorities. Joe Matt said this; however, that contradicts other authorities — and ultimately, when we look at it closely, we see that Joe Matt is actually not opposed to criticism at all, but supports it in the context of interviews. Far from undermining Matt, Jeet uses him as the final prop for an argument whose other supports are a series of imposing appellations (“Gil Kane, Robert Crumb, Art Spiegelman, etc”.)

You can see a similar process at work in this sentence:

But if we define criticism more broadly as any discussion of art or works of art, including conversations and the response of artists themselves to earlier art, then criticism is as unavoidable and essential as art itself.

The main point here, the emphatic meaning, is that “If we define criticism more broadly as any discussion of art or works of art…criticism is as unavoidable and essential as art itself.” Nestled in between that if/then construction, though is phatic content: the phrase “including conversations and the response of artists themselves to earlier art.” The second bit there is the clincher; we already know about “conversations” (a synonym with discussion), but Jeet feels it necessary to add, to highlight, the phatic fact that the response of artists to earlier art is part of criticism. The very fact that the phrase is superfluous to the argument gives it weight; it’s what Jeet decided to add even though he didn’t have to. In short, while Jeet’s emphatic meaning is a simple assertion that criticism is important, his phatic excess points again and again to artists as the exemplars and support for his statement.

In this context, I think Jeet’s note in comments that ” I think you are reading implications into my writing that weren’t meant to be there (and which other readers aren’t seeing either),” is an interesting commentary on emphatic (intentional, sometimes common sense) and phatic (excessive, implicit, requiring interpretation.) Jeet’s forswearing implications, especially those he doesn’t see. But surely part of what critics do is precisely to look for those excessive, phatic moments not, perhaps, directly connected to artist intention, but still, perhaps even all the more, important for that. Jeet’s emphatic point may not have been “criticism is valid because artists do it,” but his phatic excess shows that he validates criticism through reference to the fact that artists do it.

So here’s a final example: Gary’s response to me in comments.

It’s as if you just want to argue for arguing’s sake and since no one of any prominence is stupid enough to suggest that we substitute artists for critics or justify the validity of criticism on the grounds that artists do it, you extrapolate wildly from an essay so that you have something to argue with. You’re like a precocious 12 year old who hears the grown-ups arguing and has a compulsion to enter the fray without having the wherewithal to know what’s being discussed.

The emphatic argument is basically “you, Noah, want to argue for arguing’s sake.” But, there’s also excessive, phatic material here, perhaps best exemplified by the analogy in the last sentence. Gary accuses me of being “like a precocious 12 year old who hears the grown-ups arguing.” The phatic meaning zeroes in on generational conflict; Gary wants to infantilize me. He and Jeet are the grown-ups, I’m the precocious 12-year-old. This is especially resonant, of course, given Gary’s status as éminence grise — and given his longtime campaign to pry comics away from their status as children’s entertainment. (Indeed, the argument over who is or is not juvenile gets picked up again in later comments; I throw it at Tom Spurgeon, who volleys it back with gusto. )

Gary’s discussion is especially relevant here since he actually maps the adult/juvenile discussion onto what can be seen as an emphatic/phatic distinction. That is, he accuses me precisely of arguing for argument’s sake — for phatic (excessive) fripperies, rather than for good, emphatic reasons. Emphatic arguments are adult, phatic arguments are childish…and Gary sides with adulthood.

Supposedly. The irony is that phatic readings are, as I noted above, really what experienced “mature” critics are supposed to do. The phatic is what criticism is made of; it’s where creativity comes into criticism. It’s this kind of effort that Tom Spurgeon revealingly (and phatically) denigrates as “mak[ing] shit up.”

For Tom, making shit up, in reference to me, is a synonym for lying or, more kindly, for inadvertent but systematic misrepresentation. But, of course, making shit up is also what artists are supposed to do. And it’s what critics have to do as well; there’s an imaginative effort to figure out what the author or artist is and isn’t saying, and how that can be rephrased, rethought, recreated. The emphasis by Tom, Gary, and Jeet on intentionality, the nervousness around interpretation, does precisely the opposite of what Gary seems to hope for it. It doesn’t make writers about comics look adult and serious. It makes them look petulantly childish.

Not that Gary would necessarily be opposed to that entirely, I don’t think. After all, you don’t go around calling someone a 12-year-old if you aren’t enamored to some degree of schoolyard taunts. And Gary shows other signs of waffling around the issue of child/adult when he notes that

If Jeet has any fault as a blogger, it’s that his posts are virtually impossible to argue with — smart, literate observations that are by and large uncontroversial.

There’s a sense there that Gary wishes Jeet were maybe just a little less grown-up; that there was more juvenile, phatic pep in his posts (though, as we’ve seen, Jeet provides plenty of phatic goodness if you’re willing to look for it, and so Gary’s criticism in this case is really just unfairly projecting his own emphatic dullness.)

The emphatic point here, of course, and at length, is that I am right and everyone else is wrong. But secondarily, I want to note that the central place of interviews in comics criticism which Jeet points out seems to me to be of a piece with the tentativeness in this conversation around phatic meanings. To see the artist as the best or most important interpreter of his or her own work inevitably privilege intentionality and emphatic meaning. There’s a feeling in these discussions that phatic readings may undercut everything Gary and his cohorts have worked so hard for; that if you start playing with too many meanings you’ll end up acting like a child. Artists know best what artists say, and that emphatic meaning is and always will be, “we are not just precocious 12-year-olds, damn it.”

And that’s right, actually. Precocious 12-year-olds are smart, they’re fun, they’re surprising. If I have to choose between the 12-year-old and the intellectually stupefied eminence defending his turf…well, it’s not a hard choice to make. But really, and overall, I’d rather not pick one over the other, but just put bustles, and petticoats on both. The excess on life is art; the excess on art is crit; and the excess on both is the blogosphere with its endless rustling of frills.