“Seven cities contended for Homer when dead, Where Homer living had to beg his bread.”

At least three towns are contending for Popeye.

Above, this statue of Popeye was erected in Crystal City, Texas, in 1937.

Below, this six-foot-tall bronze statue stands in Segar Memorial Park in Chester, Illinois.

[…] whose frown

And wrinkled lip and sneer of cold command

Tell that its sculptor well those passions read

Which yet survive, stamped on these lifeless things,

The hand that mocked and the heart that fed.Ozymandias, Shelley

Chester was the birthplace of Popeye creator E.C. Segar, as recorded on the statue’s plaque:

Now, let’s examine another Popeye statue in Universal Studio’s Island of Adventure, in Orlando, Florida:

…where Popeye’s arch-foe Bluto is also menacingly present:

What differentiates these statues from the ones in Crystal City and Chester?

The Florida Popeye is set in an amusement park. It’s a prop, part of the scenery in a hundred-acre show set.

The Texas and Illinois Popeyes aren’t props. They have a weightier function, civically and semiotically. They are monuments.

Chester is obviously honoring a native son, who went forth into the vast world and achieved renown. This tradition goes back millenia; thus the Greeks of Antiquity would perpetuate the glory of a successful warrior, of a victor at the Olympic games, of a winner at the great theater festivals: that glory was also the glory of his city.

What, then, of Crystal City’s statue– considered so important that it stands sentry before City Hall?

Popeye is credited with saving the town.

Crystal City has long billed itself as the World Spinach Capital. The leafy crop dominates the agriculture of the region. But spinach has always been a hard sell, especially to children — it is bitter. Compound this dissatisfaction with the withering effects of the Great Depression, and Crystal City found itself facing disaster.

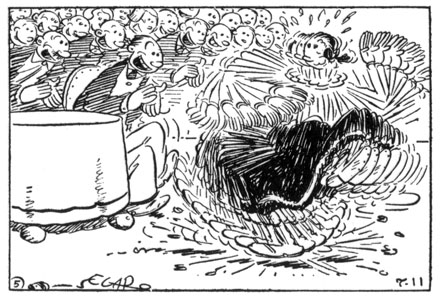

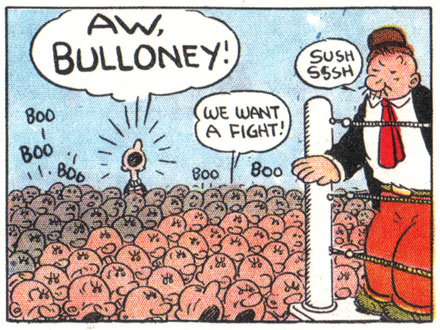

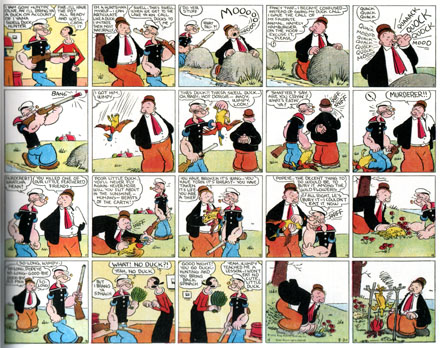

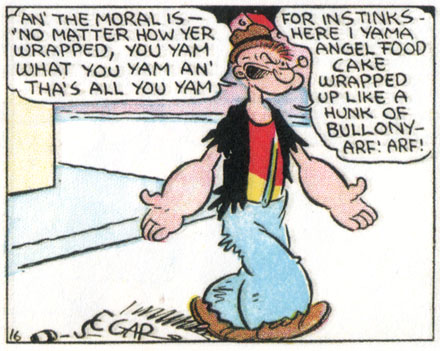

Along came Popeye, his great strength attributed to his consumption of spinach (less so in the strips, conspicuously so in the animated cartoons.) Kids all over America — over the world– internalized the sailor’s profession of might:

“I’m strong to the finish, ’cause I eat me spinach; I’m Popeye the Sailor Man!” (Toot toot!)

…and they devoured their spinach with gusto. (I, too, fell for the propaganda. In fact, spinach is, of course, no builder of strong bodies– it isn’t even particularly rich in iron, the oft-cited source of its potency.)

The spinach industry was saved. The grateful burghers of Crystal City, thus, put up their statue as a votive thanksgiving– another monumental tradition.

( That statue outside City Hall isn’t, contrary to its plaque’s assertion, the one inaugurated in 1937; it’s a modern copy, while the original is inside the building.

So it’s a simulacrum of a sculpture of an animated cartoon character based on a comic strip character inspired by an acquaintance…I’m getting situationist vertigo, here.)

Crystal City is by no means alone in its gratitude to this cartoon character. Alma, Arkansas, also claims the crown of World Spinach Capital, and celebrates Popeye in bronze:

According to one report:

Popeye Park, built in a former vacant lot, is a big part of Alma’s image makeover. It is a place where people can get out and look at things. The centerpiece statue is glorified atop a fountain, and according to Mark the park will soon have two kiosks with flat screen monitors that will relate the history of Alma and Popeye. A large mural is planned for the wall of the adjacent water company building, with hidden Popeyes to engage children (and maybe the tour bus drivers).

This is getting out of hand, some may think. And why Alma, anyway? Because it’s the site of the Allen Canning Company, producers of Popeye Spinach:

…at one point producers of 63% of the world’s canned spinach.

So the livelihood of many Alman households depend on this brand– this cartoon. What’s wrong with a little sculptural homage?

Yet one might find this unsettling.

As the semioticians remind us, we live in a world of signs; some overt and loud, some whispering, some in the dog-whistle domain of the subliminal.

A monument is a bellowing, gigantic voice in this landscape; it aggressively forces its meaning on us; small wonder monuments are the favorite markers of tyrants’ rule.

Prudence, thus, traditionally presides over the choice and placement of public monuments. Commissions debate them, the public is consulted; they are scrutinized for glorification of the unworthy, or for partisan agendas. Often they are isolated from the city proper, as in cemeteries.

The subjects of monumental statuary tended ever to be divine: gods and saints, the Christ; or heroic– gallant soldiers, philanthropists, poets and other writers. One might legitimately question the sculpted exaltation of corporate cartoon characters. In contrast to the Orlando Popeye, those in Crystal City, Alma, and Chester are free of irony– indeed, almost of playfulness.

Perhaps we should judge these statues by their function. This image of Garfield stands just outside a children’s hospital:

Who can object to an attempt to make a sick child smile, or to allay his fears with a familiar old “friend”?

But it’s still troubling when an online search for ‘Garfield statue’ returns more results for the cartoon cat than for the effigies of James A. Garfield (1831– 1881), America’s 20th president, felled by a deranged assassin’s bullet:

We shall later show sculpture inspired by the strip Peanuts.

A different Peanut can be seen below–‘ Mr Peanut’ , the corporate mascot of the company Planter’s.

Such commercial images are already omnipresent in our visual ecology, so it is not over-curmudgeonly to hope their monuments do not proliferate, unless it be with the wit of an Andy Warhol or of a Jeff Koons:

Well, at least he offers you a seat.

Travel to Metropolis, Illinois, and you find monumentalism tipping slightly towards idolatry.

As readers of the Superman comic know, the mighty hero makes his home in Metropolis– a booming city modeled on Cleveland and New York.

Metropolis, Ill., is a far more modest place. But in 1972, D.C. Comics and the state of Illinois officially declared it to be the hometown of Superman. This was a prelude to a titanically hubristic enterprise: The Amazing World of Superman.

Concept Art by Neal Adams. For more, click here

There were to be a museum and an amusement park dedicated to the ur-superhero, the whole dominated by a 200-foot-tall statue of Superman. The entire venture collapsed.

Today, Metropolis’ exploitation of Supes is much more modest, but definitely there… as evidenced by this fifteen-foot bronze polychrome statue:

Metropolis celebrates the Man of Steel every way it can. The local bank is “home of super financial services.” The town newspaper calls itself The Planet. A sign in the grocery store informs customers: “Just as Superman stands for truth, justice and the American Way, Food World stands for quality, convenience and friendly service.”

Below, Bill Griffith‘s pinhead clown Zippy pays the statue a visit:

It’s a typical absurdist Griffith gag, but he makes a larger point: it’s wrong to invest your hopes in a fake idol. There’s no Santa Claus, no Tooth Fairy, no Superman– even metaphorically.

Metropolis seems to have learned this lesson from the 1972 fiasco. Its exploitation of Superman is mostly limited to photo ops for tourists:

…or Supes collector George Hambrich’s ‘Super-Museum’:

… or the annual Superman Celebration:

Special guest star at the 2010 Celebration:

Yep, U.S. President and lifelong comic book fan Barak Obama.

Incidentally, this wasn’t the first Superman statue erected in Metropolis. First came a fiber-glass 7-footer.

Problem was, the locals took to testing the hero’s noted bulletproof powers, resulting in a sorry Swiss cheese of a statue. It was replaced by the current bronze colossus.

Ah, yes, the Colossus. The need to extract awe from sheer size alone, as Emperor Nero did with the giant gold statue of himself in ancient Rome. All over America, you’ll find colossi of another kind: celebrating the folk giant lumberjack, Paul Bunyan:

Bunyan, however, is a prominent example of ‘fakelore’– artificial modern folklore; in fact, the giant’s tales were all spun by a copywriter for a lumber company. A visual simulacrum (the statue) to represent a conceptual one (the fakelore.)

And the size of the colossus seems to validate this manufactured myth.

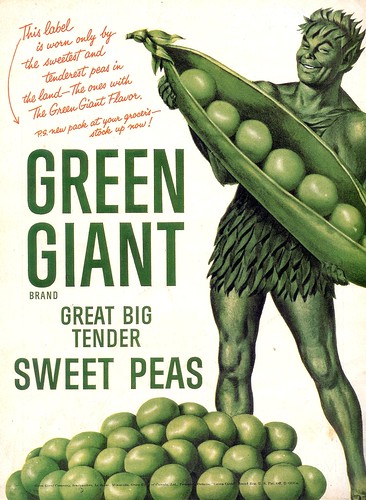

In Blue Earth, Minnesota, stands a towering figure drawn from one of our other modern sources of pseudo-icons, advertising:

“Good things from the garden,

Garden in the valley,

Valley of the Jolly Green Giant!

Some are green-snappin’ fresh

Kitchen-sliced to taste the best

Tender beans are comin’ from the valley! (From the valley!)Good things from the garden,

Garden in the valley,Valley of the Jolly (‘ho, ho, ho’) Green Giant!”

— Leo Burnett

The Green Giant is the mascot of a vegetable canning company belonging to agribusiness behemoth General Mills.

As with Popeye, the locals in Minnesota show pride and gratitude towards a symbol of their livelihood.

Why, man, he doth bestride the narrow world

Like a Colossus; and we petty men

Walk under his huge legs, and peep about

To find ourselves dishonourable graves.–William Shakespeare, Julius Caesar

Perhaps popular enthusiasm goes too far, though, when the locals adopt the name of a mass-media character. This has happened at the town of Idaho Springs, when the residents of its Squirrel Gulch district renamed it Steve Canyon, after the comic-strip adventurer created by Milton Caniff.

In 1950, they persuaded the federal government to commission a giant limestone sculpture of the cartoon aviator for their town. Its plaque reads, in part,

“The United States Treasury salutes Steve Canyon and through him, all American cartoon characters who serve the Nation.”

Say what?

Ah, well, perhaps I’m merely indulging in cultural snobbery. It’s true that a lot of the statues above are way cool, after all.

And at least they don’t celebrate tyrants:

Stalin

Lenin

Kim Il-Sung

Walt Disney

All right, that was a cheap shot… but the juxtaposition of similar images makes one think.

Disneyland bills itself “the happiest place on Earth”. Happiness is mandatory. Well, in what other sort of place is happiness mandatory? The “workers’ paradises” of Communist countries.

Disneyland also resembles them by its degree of control. The entire park is a panopticon. It even has a ‘secret police’– the security guards are there, but not in uniform.

Disney headquarters, as designed by Michael Graves: the cartoon as slave to the corporation

All four statues show the same gesticulation towards… what? The glorious future?

Let’s hope Walt and Mickey’s statue doesn’t suffer the same fate as Saddam Hussein’s:

A final farewell to the colossus…with the fearsome effigy of cloud-gathering Zeus in the French ‘Parc Astérix’ amusement park:

;

Yet, pass humbly between his divinely titanic legs and look up:

<

Tch! This is the Underwear of the Gods? Feh.

Meanwhile, in Philadelphia, we find this effigy of Sylvester Stallone— sorry, of Rocky Balboa:

Bronze, neoclassical pedestal-mounted kitsch or celebration of the human spirit? Celebration of Hollywood, certainly.

And along those lines comes another bad idea. Detroit will see a statue of Robocop.

What are they thinking over in Motown? The city is depicted in the Robocop films as a hellhole, a behavioral sink rancid with corruption and violence. (Well, okay, but they don’t have to dwell on it.)

But I suppose such masochism is to be expected. Kneel to our media overlords.

Wow, I’m getting grouchier by the second. Don’t I see any place for public statuary? Actually, I do, as I shall note in my appreciation of the St.Paul Peanuts statues.

St. Paul, Minnesota, is another city that honors a famed native son– Charles Schulz (1922– 2000), creator of the comic strip Peanuts — with a series of bronze sculptures.

But these are anything but monumental: they were specifically designed to be kid-friendly. They exude charm allied with modesty, which was also the case for the strip and its author.

Along these lines, in Hartlepool, England, we find a statue of their own native son Reg Smythe‘s comic strip hero Andy Capp:

The statue was controversial, actually, as Andy was a wife-beater among other things. And note that his ever-present cigarette was censored.

Now, note the proportions of head-to-body in the statue and compare them to those of the drawn Andy:

About three heads tall for the cartoon, about five for the statue. Why?

So that people can do this:

That’s right– they can hug it, clink glasses with it… interact with it! People want to be pals with the cartoons!

Note, too, the absence of a pedestal. The character is on the same footing as us.

This is key: people have strong affection for “their” cartoon characters; they literally take them into their homes, with the newspaper or through the tv screen. So the best cartoon sculptures will promote a feeling of affectionate intimacy.

Here, in Dundee, Scotland, are Desperate Dan and Dawg:

… and Minnie the Minx:

Again in England– in Ipswich– Carl Giles‘ beloved Grandma character:

But my favorite interactive cartoon sculpture is this one of Mort Walker‘s Beetle Bailey: you can actually sit and have a drink with him.

And my favorite non-cartoon interactive public sculpture is in London. A Conversation with Oscar Wilde is designed as a bench; you’re supposed to sit and tell Oscar the latest gossip:

The statue of Tintin in Brussels used to be on a pedestal in a park; when it was moved to a city street, the pedestal was removed, and you can now have a playful chat with the globe-trotting boy reporter:

This more intimate, anti-monumental style seems to be catching on. Here’s James Joyce in Dublin:

As a final example of interactive statuary, consider the much-beloved Alice in Wonderland group in New York’s Central Par, over which I scrambled as a child– a tradition that continues, it would seem:

There is more to be said about the curious class of cartoon sculpture; about its polysemic ambiguity, about the colonisation of public space by corporate imagery,about kitsch and irony, about ….

But :

Now its time to say goodbye

To all our company.Em-eye-cee-

“See you real soon !”

Kay-ee-wy-

“Why? because we like you!”

Em-oh-you-ess-ee

–signoff song for the Mickey Mouse Club

A great guide and source of information about similar curiosities is http://www.roadsideamerica.com/