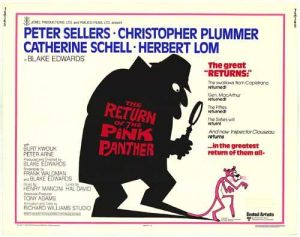

My sister and I spent every weekend of 1975 at my mother’s one-bedroom apartment, with afternoons at the zoo, swimming pool, or matinee of that week’s PG, Escape to Witch Mountain, Funny Lady, The Return of the Pink Panther. Money—I realized later—was tight. My mother skipped lunches to balance the once-a-weekday dinner out with us too. Her father had been a Westinghouse vice president, so even after his death her family could afford to stay in their large house on a treed cul-de-sac. But instead of collecting alimony after divorcing my father, my mother started a research career as an entry level lab tech feeding rats on weekends—always our Sunday morning adventure.

I’ve not seen The Return of the Pink Panther since, but the scenes are still vivid—that black-suited burglar creeping past museum security to pinch the precious diamond from its alarm-triggering pedestal. The Panther was the diamond, not the thief, which confused me. It should have been The Return of the Phantom. Though technically the Phantom didn’t return either. That was his wife, Lady Claudine, in the bodysuit, goading her husband, Sir Charles, out of a posh but boring retirement.

A life of luxury is a dangerous thing. Victorians feared it would destroy Mankind, starting at the top of the ladder with the Aryan aristocracy. “The white races of Europe,” warned E. Ray Lankester in his Degeneration: A Chapter of Darwinism, “are subject to the general laws of evolution, and are as likely to degenerate” and become “intellectual barnacles.” In fact, any “set of conditions occurring to an animal which render its food and safety very easily attained seem to lead as a rule to Degeneration.” Lancaster likens the process to how “an active healthy man sometimes degenerates when he becomes suddenly possessed of a fortune.” The problem is the “habit of parasitism” wealth produces: “Let the parasitic life once be secured, and away go legs, jaws, and eyes; the active highly-gifted crab, insect, or annelid may become a mere sac, absorbing nourishment and laying eggs.”

Half of the rats we fed Sunday mornings were getting heavy doses of grain alcohol in their feeding tubes. They’d just doze in the backs of their cages, quietly twitching with DTs. A philanthropic billionaire in Arthur Conan Doyle’s 1891 The Doings of Raffles Haw gets similar research results when he tries to help the world by sharing too much of his fortune. A vicar observes how an “ambitious, pushing, self-reliant” young artist, whose first words if you met him “were usually some reference to his plans, or the progress he was making in his latest picture,” now “does nothing. I know for a fact that it is two months since he put brush to canvas.” By the final chapter, Raffles Haw recognizes the error of his ways, writing in his suicide note: “alas! the only effect of my attempts has been to turn workers into idlers, contented men into greedy parasites, and, worst of all, true, pure women into deceivers and hypocrites. . . . The schemes of my life have all turned to nothing.”

So what is a well-born to do? E. W. Hornung offered a very different remedy. He strips his cricket-playing protagonist of his riches, all that easily attained food and safety, and evolves him into a gentleman thief who has to risk imprisonment to maintain his lifestyle. “Why settle down to some humdrum uncongenial billet,” asks A. J. Raffles, “when excitement, romance, danger and a decent living were all going begging together?” Sure, a life of burglary is immoral, but wouldn’t the aristocracy rather be robbed by a Keats-quoting “Amateur Cracksman” than a professional ruffian from the lower classes?

It’s a pleasantly perverse solution, one Hornung crafted in defiance of his brother-in-law, Sir Arthur. The author of Sherlock Holmes had yet to be knighted when Hornung published his first Raffles tale in 1898, but the gentleman thief turns Doyle’s knightly detective on his head. Hornung steals not only the name Raffles from Doyle’s billionaire but the character of Watson too. After Raffles rescues another destitute socialite from suicide, the narrator sidekick rises to their new life: “The truth is that I was entering into our nefarious undertaking with an involuntary zeal of which I was myself quite unconscious at the time. The romance and the peril of the whole proceeding held me spellbound and entranced.”

The Raffles mutation proved advantageous in the literary market place too—though always with a strain of Robin Hood do-goodery. Soon gentlemen thieves were relieving their boredom across magazine racks and bookshelves: R. Austin Freeman and Dr. John Jones Pitcairn’s Romney Pringle (1902), O. Henry’s Jimmy Valentine (1902), Arnold Bennett’s Cecil Thorold (1904), Maurice Leblanc’s Arsène Lupin (1905). Orczy’s altruistic Scarlet Pimpernel steals fellow aristocrats instead of diamonds, but his League of sidekicks are just more thrill-seekers: “for this is the finest sport I have yet encountered.—Hair-breadth escapes, the devil’s own risks!—Tally ho!—and away we go!”

After the Pimpernel, flowery aliases followed gentlemen thieves up the ladder too: Louis Joseph Vance’s Lone Wolf (1914), Frank L. Packard’s Gray Seal (1914), Roderic Graeme’s Blackshirt (1925), Leslie Charteris’ Saint (1928). Masks and signature emblems evolved into the formula too, beginning with the Gray Seal’s adhesive trademark found on the safes he cracks to the “P” blazoned glove Lady Claudine left on that museum pedestal. George E. Brenner preferred a literal calling card with his hero’s catch phrase: “The Clock Struck.”

The 1937 Clock beat Superman to comic books by a year, but it took Bob Kane and Bill Finger to raise a parasitic well-born into full superhero status. The “young socialite” Bruce Wayne signs his notes with a bat stamp, while affecting Lankester’s habit of parasitism: “Well, Commissioner, anything happening these days?” That’s Batman’s first 1939 panel. The avenge-the-dead-parents motive was an afterthought spliced in months later. The original Bruce was just bored.

Hornung’s Raffles faces the same problem. As a billionaire, “perhaps the only one in the world,” he feels a great responsibility: “I have not been singled out to wield this immense power simply in order that I might lead a happy life.” That was 1891, so the world population of altruistic billionaires has risen since. Bill Gates is worth about $78 billion, and, like Raffles Haw, he wants to give lots of it away. “My full-time work will be the foundation for the rest of my life,” he said last year. If that doesn’t keep him happily busy, Lady Melinda may have to slip into that Phantom outfit again.

David Niven played the Phantom in the original 1963 The Pink Panther—sort of a comic sequel to his 1939 Raffles. For his 2009 remake, Steve Martin swapped the Phantom for the Tornado, another female thief, the first played by Grace Cunard in the 1914 My Lady Raffles. My mother, the daughter of a corporate VP, did not become an aristocratic burglar. She had the push, ambition and self-reliance to evolve her rat-feeding job into a Ph.D. and more epidemiological publications than I can count.

But when she lost her last multi-million dollar research grant, her life devolved into early Alzheimer’s. She’s now living in an assisted living facility near my sister, where food and safety needs are easily attained. She says she’s gotten quite good at bingo, a game of chance not unlike a raffle or the stock market. Her retirement portfolio is making a killing right now. I visit on weekends, usually once a month. I can’t remember the last time we saw a movie together, but I may suggest a matinee on my next visit. Everyone needs an afternoon adventure.