Alan Moore’s Providence has been well served by the online community of researchers and critics over the past year. Of greatest note, perhaps, are the detailed annotations at the Facts-Providence blog. It would also be remiss of me not to mention Craig Fischer’s long overview of Alan Moore and Jacen Burrows’ Lovecraft cycle at The Comics Journal.

For once the backcover blurbs accompanying Providence have been largely correct. The work is easily Moore’s most heavily researched and intricately devised comic in years. Yet of the many mysteries of Providence, there remains one which has sternly defied explanation.

Why did Alan Moore choose Jacen Burrows to draw Providence?

Was it a true appreciation of Burrows’ art, a choice made for the sake of consistency (since Burrows worked on The Courtyard and Neonomicon), some connection on the personal level, the path of least resistance (Burrows being Avatar Press’ best artist), or some combination of all these (and more)? Whatever the reasons, I think there is little doubt that the choice was fully within Moore’s hands.

Some perspective on this issue might be gained by listing out a few of the artists who have worked with Moore on his long form works over the years: Stephen Bissette, Brian Bolland, Eddie Campbell, Alan Davis, Melinda Gebbie, Dave Gibbons, Ian Gibson, Gary Leach, David Lloyd, Kevin O’Neill, Bill Sienkiewicz, Curt Swan, John Totleben, Rick Veitch, J.H. Williams III, and Oscar Zarate.

Some might argue that the work of Jacen Burrows exceeds one or two of these artists, but I think it’s safe to say that many more would consider his contribution to Providence to be somewhat indifferent and strangely out of place among these illustrious names. Certainly, on a purely technical level, it is very hard to place Burrows ahead of most of these cartoonists but this also assumes that this was Moore’s primary consideration in choosing Burrows to be his partner on Providence.

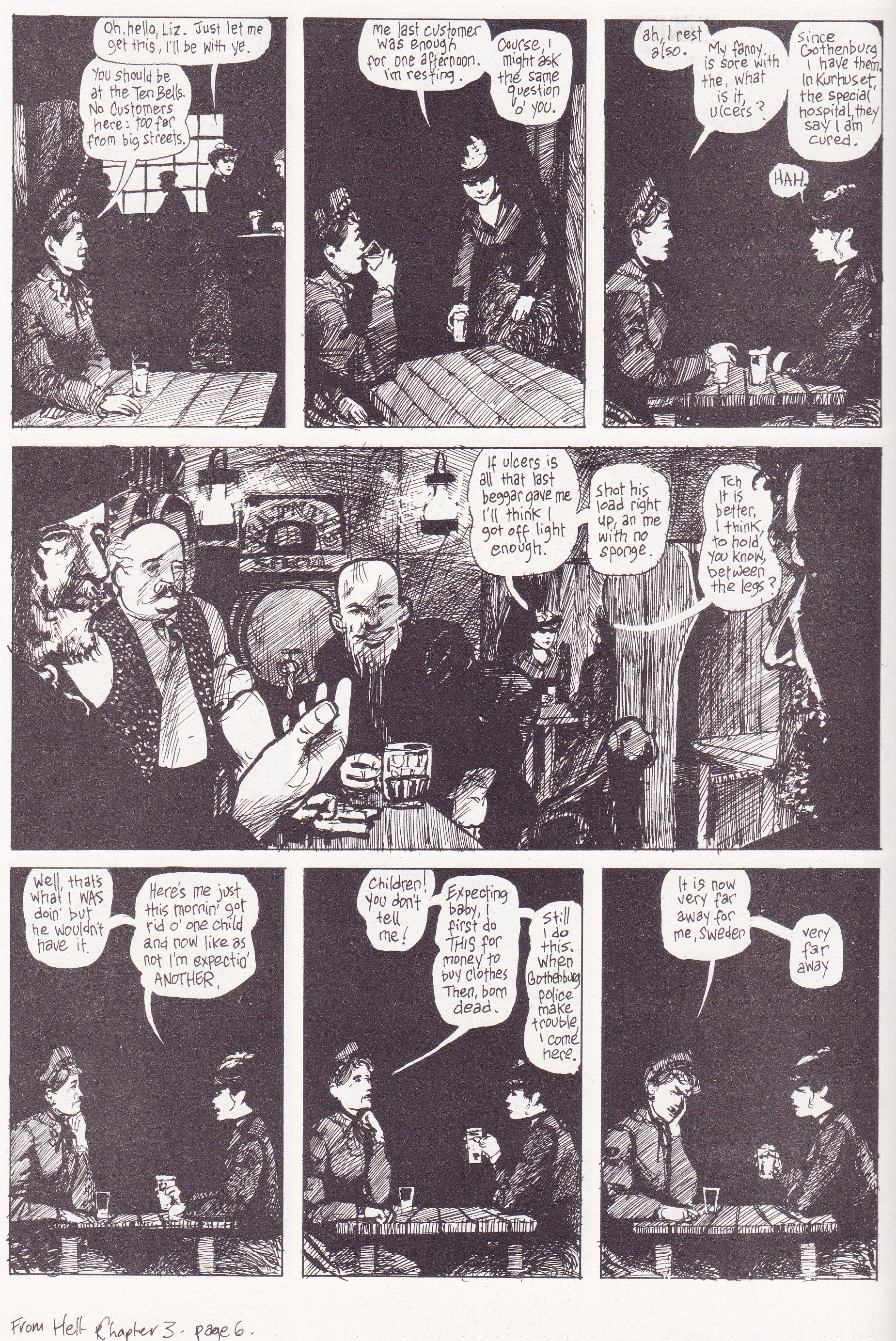

If Moore’s contributions are generally always visible in his careful structure at the level of both page and book, his obsessive research, and his sometimes baroque dialogue and themes; then the contribution of his collaborators is even more apparent. Eddie Campbell’s contribution to From Hell is an unrelenting crepuscular inking, the rush of lines swiftly scratched across the page suggesting something indistinct, something hidden; the figures in deep black coats suffocating entire panels in impenetrable night. When William Gull does his work, he is the darkest point in the room, his tunic bleeding into the stains hemorrhaging from his victims; the rest is a kind of rolled-on hatch work candlelight.

A quick flip through the scripts of From Hell at hand suggest that Moore was capable of giving Campbell free reign to exercise his imagination (and research) in a number of scenes, while Campbell himself felt free to change Moore’ suggested panel progressions and compositions across entire tiers of panels.

By comparison, J. H. Williams’ work on Promethea is almost lightness personified; the manifestations of the comic’s matriarchal thaumaturgy might be colorful, labyrinthine, and decadent but it rarely seems truly frightening. Which is a roundabout way of saying that Moore seems to choose his partners with great intent (more so as his reputation has grown), seemingly tailoring his scripts to their abilities. Which makes the choice of Burrows all the more puzzling.

There is of course the simple matter of reliability and temperament with Moore’s experience on Big Numbers being the main point of provocation (Bill Sienkiewicz having shown a distinct distaste for working on Moore’s detailed scripts). This is perhaps one of Burrows’ main selling points—his willingness to subsume much of his own artistic vision to that of Moore’s; you can almost sense his desire to pay obsessive attention and deference to the details of the script. The plainsong delivery of Providence seems to provide us with an almost unfiltered expression of Moore’s writing (which is arguably not the point of a collaborative piece where we want both distinct voices to be heard).

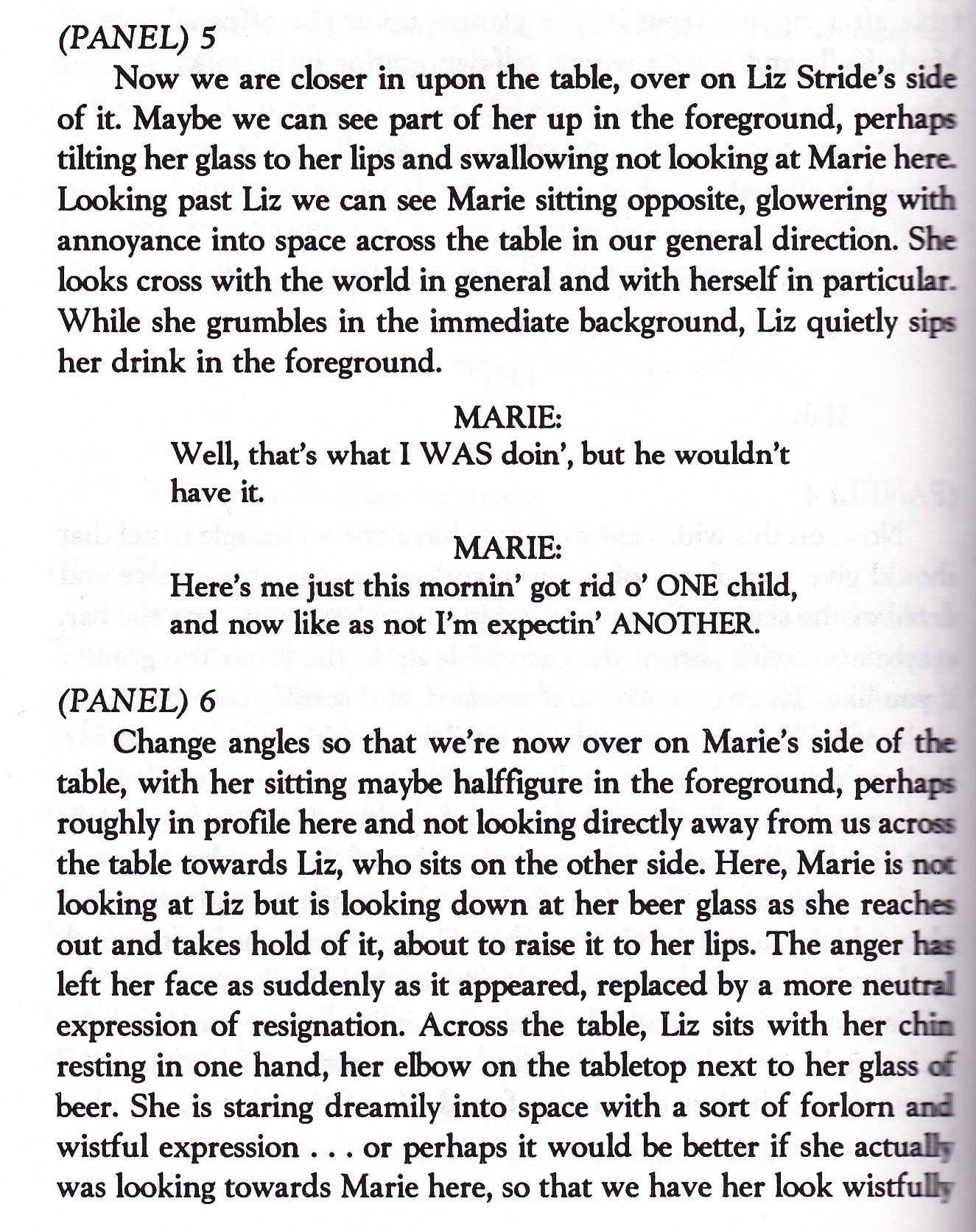

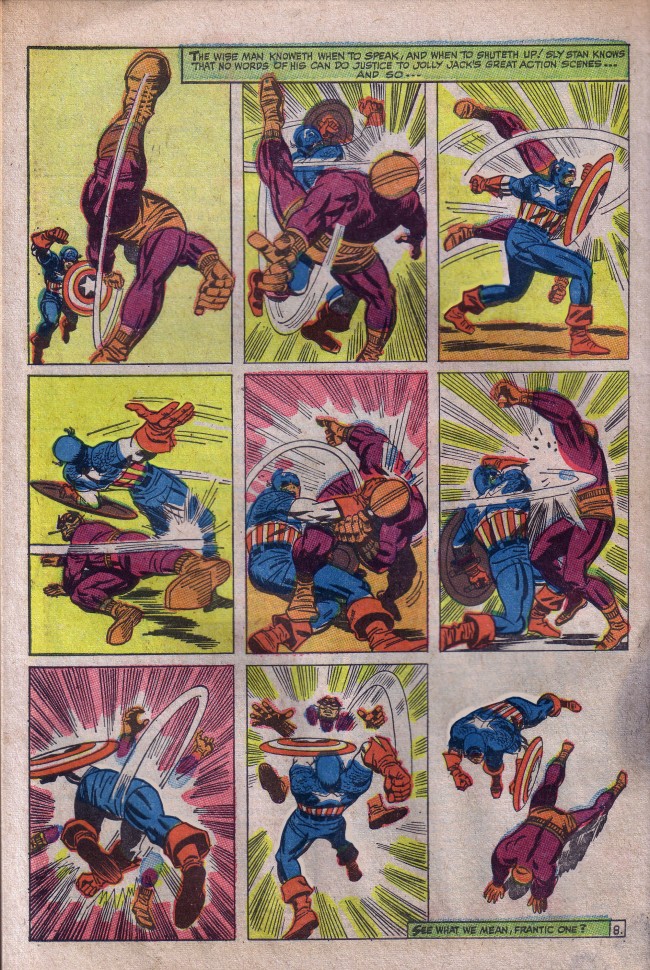

The clarity of Burrows’ expression is such that almost every element depicted has the impression of being placed in space under the direction of Moore (with a modicum of artistic direction by Burrows). What I am describing is the effect of Burrows’ drawing style and it may be something very far from the truth—its scrubbed cleanliness, its theatrical violence, its precision if not in draftsmanship, then in obsessive depiction and placement. Consider Providence #5 where Robert Black and Hekeziah Massey ascend and descend the same set of steps on different pages, the disparity in their heights across two different pages presumably accounted by the height of the steps they are traversing.

Such is Burrows’ attention to detail that the reader is left to wonder if the height of the steps is sufficient to account for the difference in their heights as seen from the exterior of the house (Massey is considerably shorter than Black as is). The house is based on that in Lovecraft’s The Dreams in the Witch House; an abode existing in indeterminate time and space. The branches which cast their shadows across the facade of Massey’s house were first seen on the cover to issue one of Providence (depicting the site of Lovecraft’s story, Cool Air) suggesting an arcane connection. In this and other scenes, Burrows seems almost mathematical in transcribing Moore’s script.

In this sense, Burrows is the artist who most resembles Dave Gibbons as far as Moore’s oeuvre is concerned. That earlier pairing appears to have been a bit more collaborative in nature; more taken with the squalor and boisterousness of life and drawing. Whatever your opinion about Gibbons’ work, there is something to be said for the way he managed to work around Moore’s voluminous scripts despite the constrictions of the nine-panel grid—a format which forced him to engage in a series of medium shots and close-ups for much of Watchmen.

This is not to minimize Burrows’ own contributions if Dave Gibbons’ experience on Watchmen is anything to go by. Here’s a typical interview by Gibbons explaining his contributions just before the launch of the Watchmen movie.

“…people unacquainted with graphic novels, including journalists, tend to think of Watchmen as a book by Alan Moore that happens to have some illustrations. And that does a disservice to the entire form, because comics are stories in words and pictures.”

“…like the notes where I plot the rotation of a perfume bottle through the air — might not be particularly obvious to anyone who reads it. But those who do will note the consistency, the reality behind it all that exists in great depth. It gives it a more magical quality…”

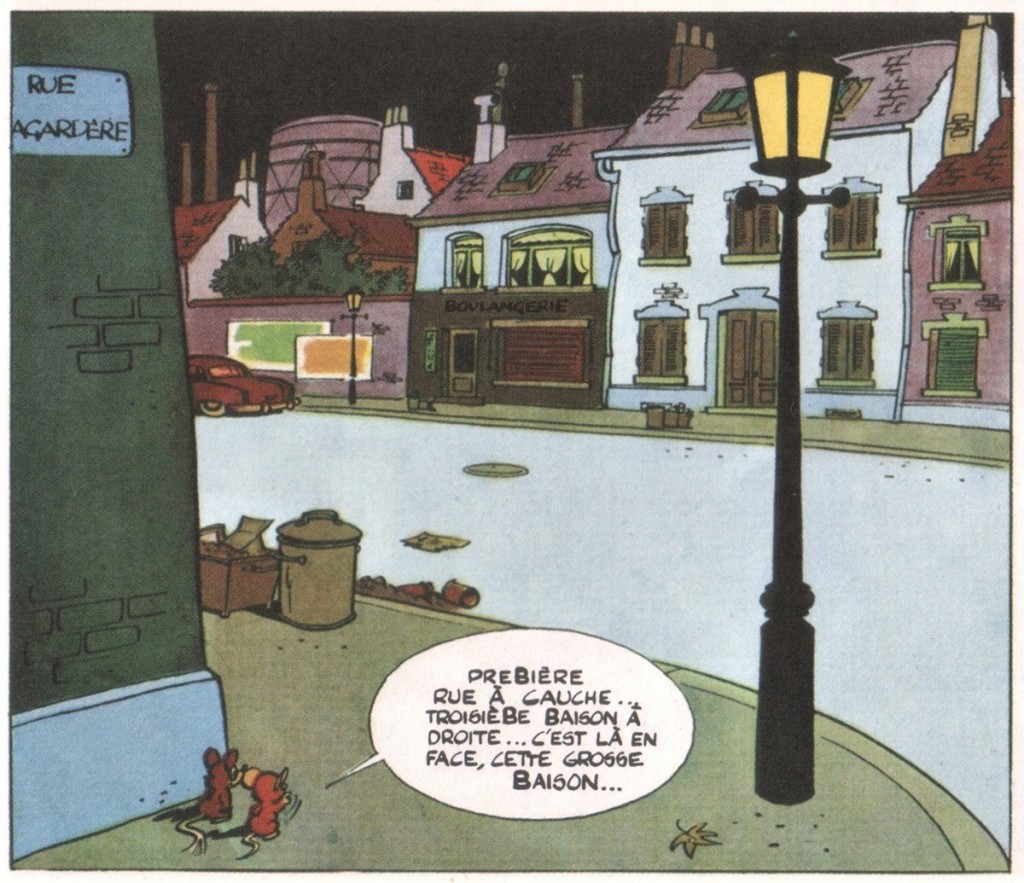

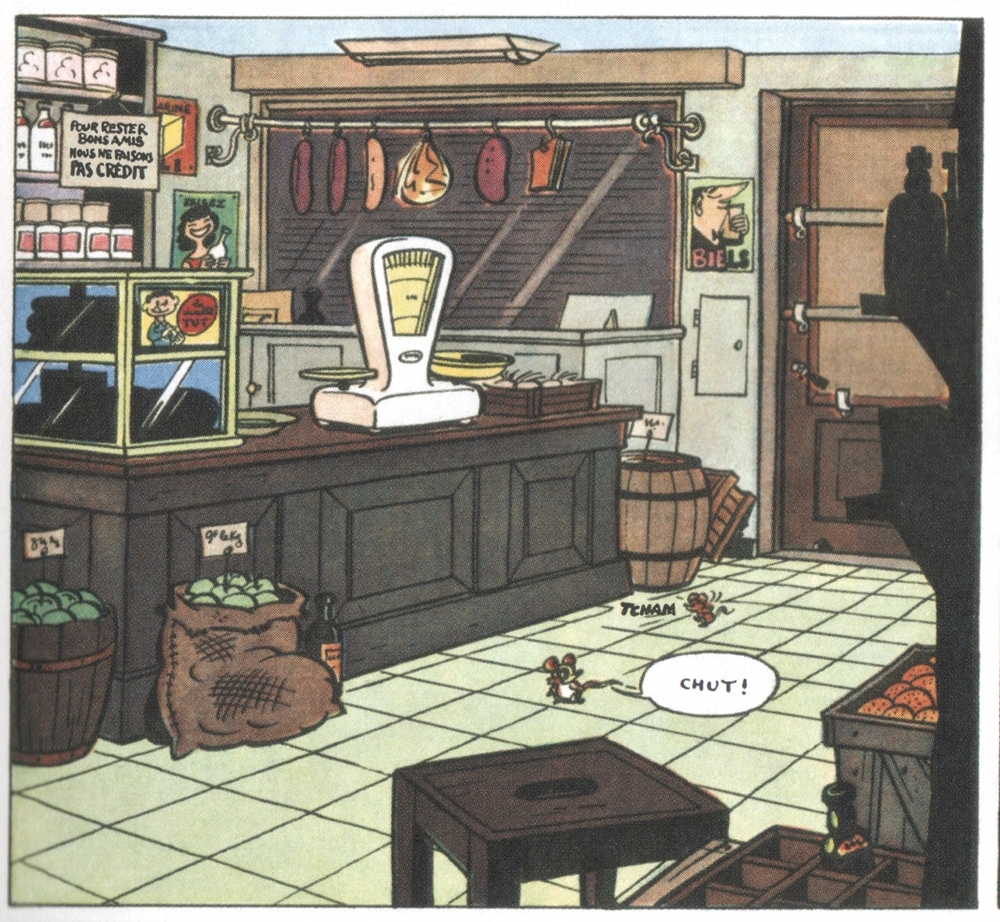

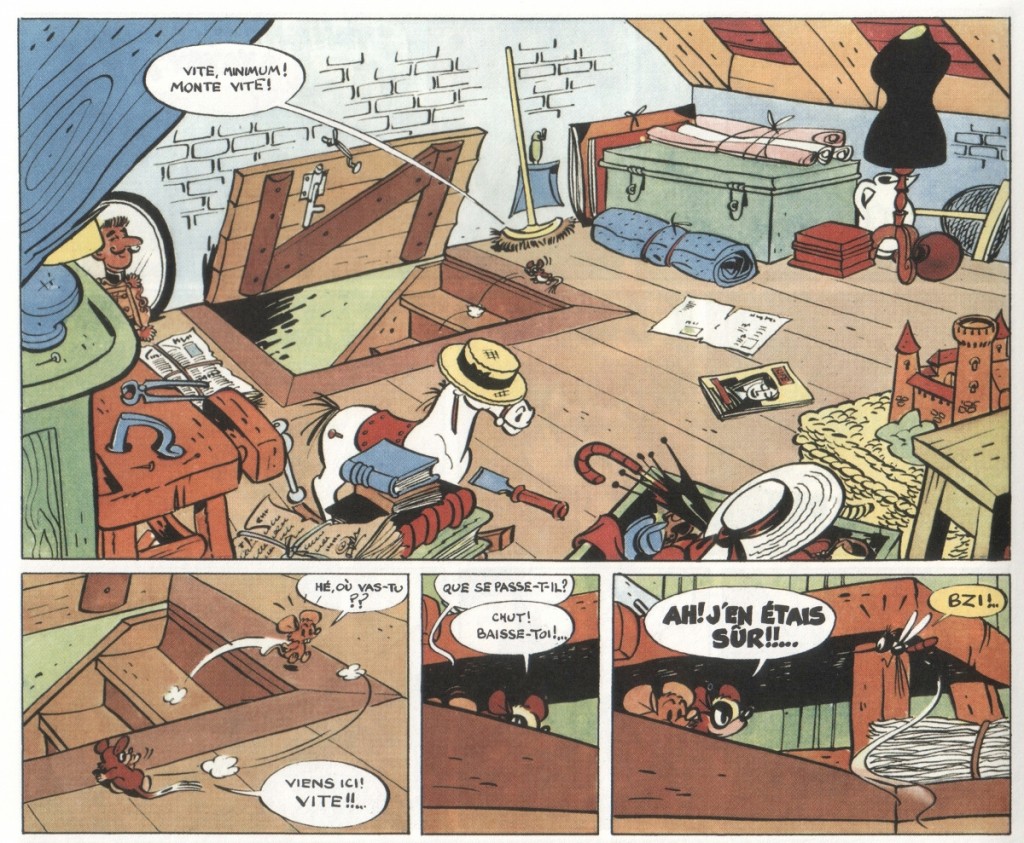

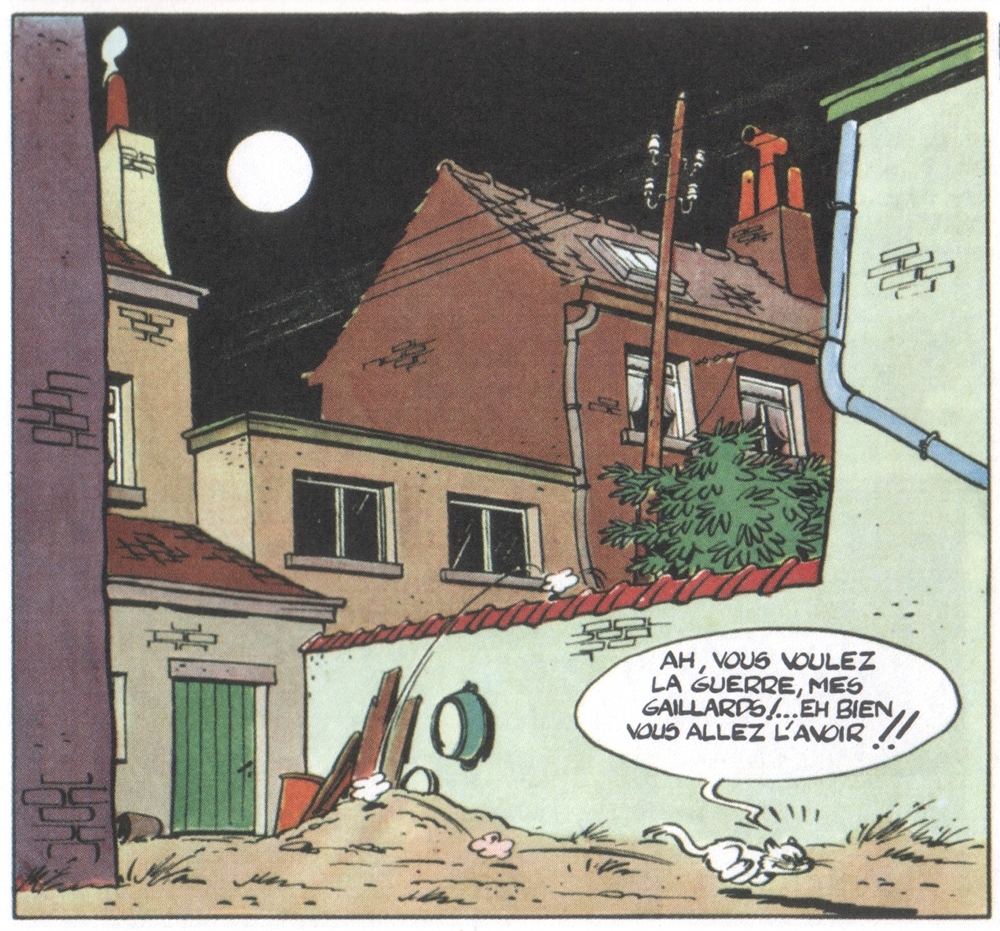

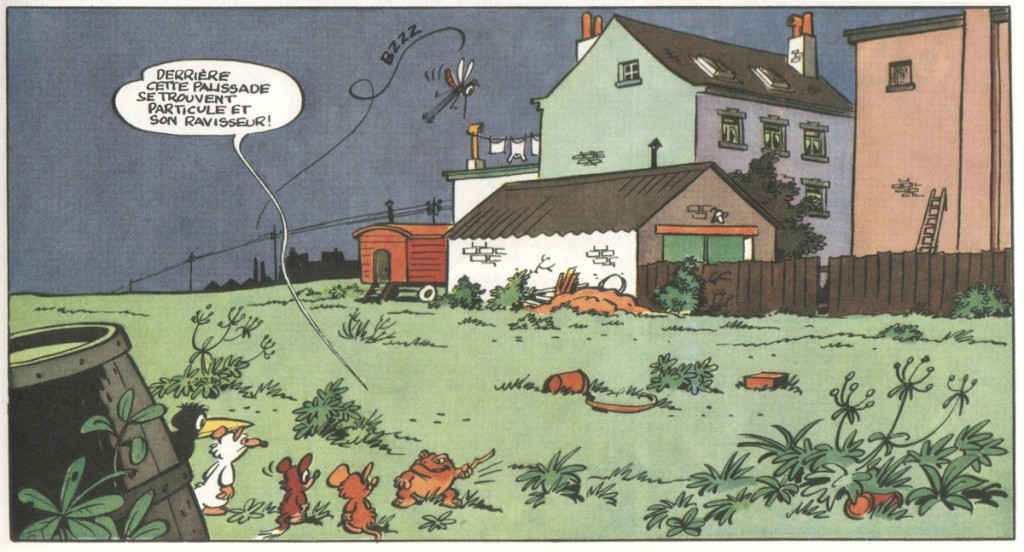

Burrows describes a somewhat similar experience for his work on Moore’s scripts in various interviews. At the very least, the reader will find a substantial amount of his contributions in the character designs, the style of dress, and the everyday objects which populate Providence—the kinds of things which people only notice when they go horribly wrong. Burrow’s greatest contribution appears to be in the recreation and reimagining of various outdoor locales. While he is not an architectural maestro of the level of a François Schuiten (or even a Dave Gibbons), he seems most comfortable when dealing with the facades of buildings (his interior spaces are another matter; see below). Perhaps the photo referencing helps in many of these instances.

An uncredited writer at Facts-Providence is one of the rare unadulterated defenders of Burrow’s work and suggests other aspects of his art which might be due some appreciation:

“As far as gore and grue goes, it can be honestly said that few artists in the industry get quite the mileage out of their anatomical studies as Burrows does—both in terms of making sure every organ and muscle is in its correct place, and for not shying away from the nipples and genitalia.”

“…the sense of space. Some of the subtle but effective visuals and layout choices focus on shifting perspectives in the same space, with visual cues directing the readers’ attention rather than dialogue, forming an effective visual rhetoric.”

In any case, Moore has persisted with Burrows and his faith in the artist has paid off in a way. Providence is undoubtedly Burrows best comics work to date, and it is done with a level of confidence and brio which suggests a greater sense of mission brought on by the new script. The oft cited stiffness has been reduced in severity throughout. Much of this has to with a better grasp of proportion, a more naturalistic placement of figures within each panel, and a greater variety in his panel compositions.

Having said this, some awkward foreshortening still rears its head at times and there are other more significant difficulties.

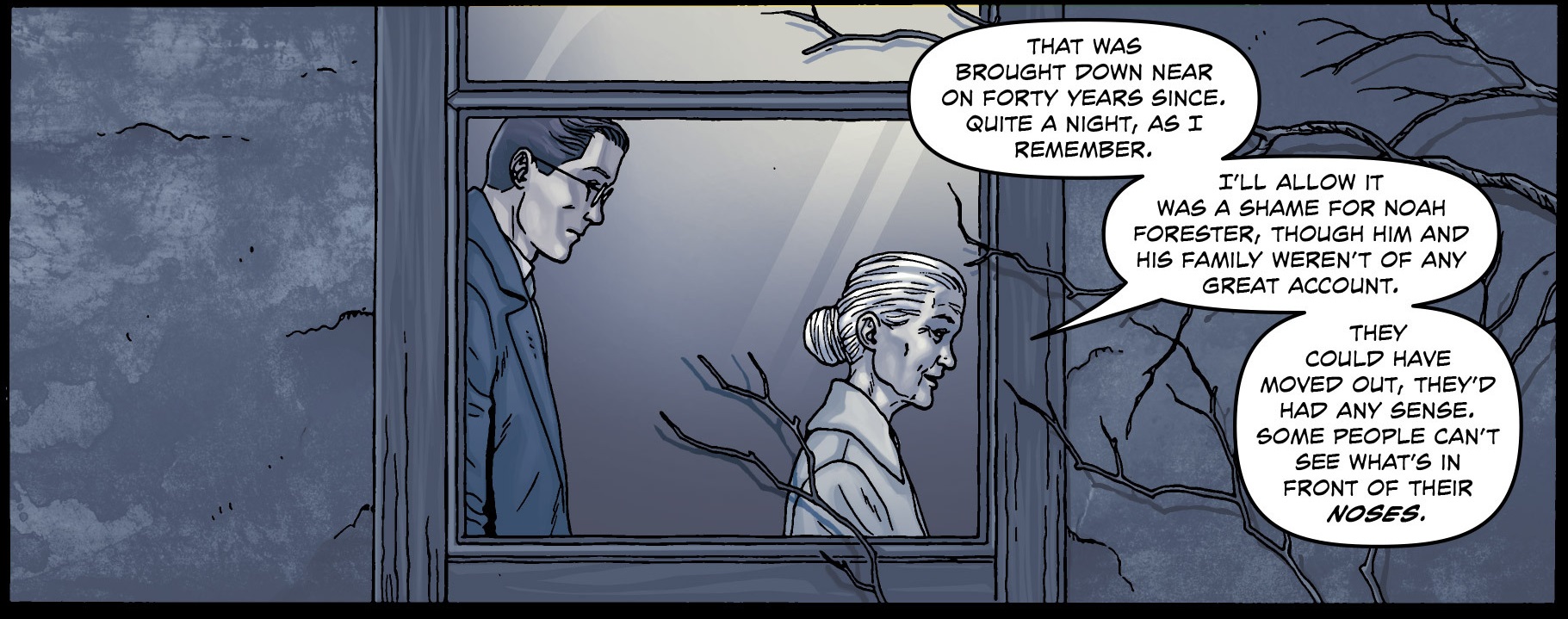

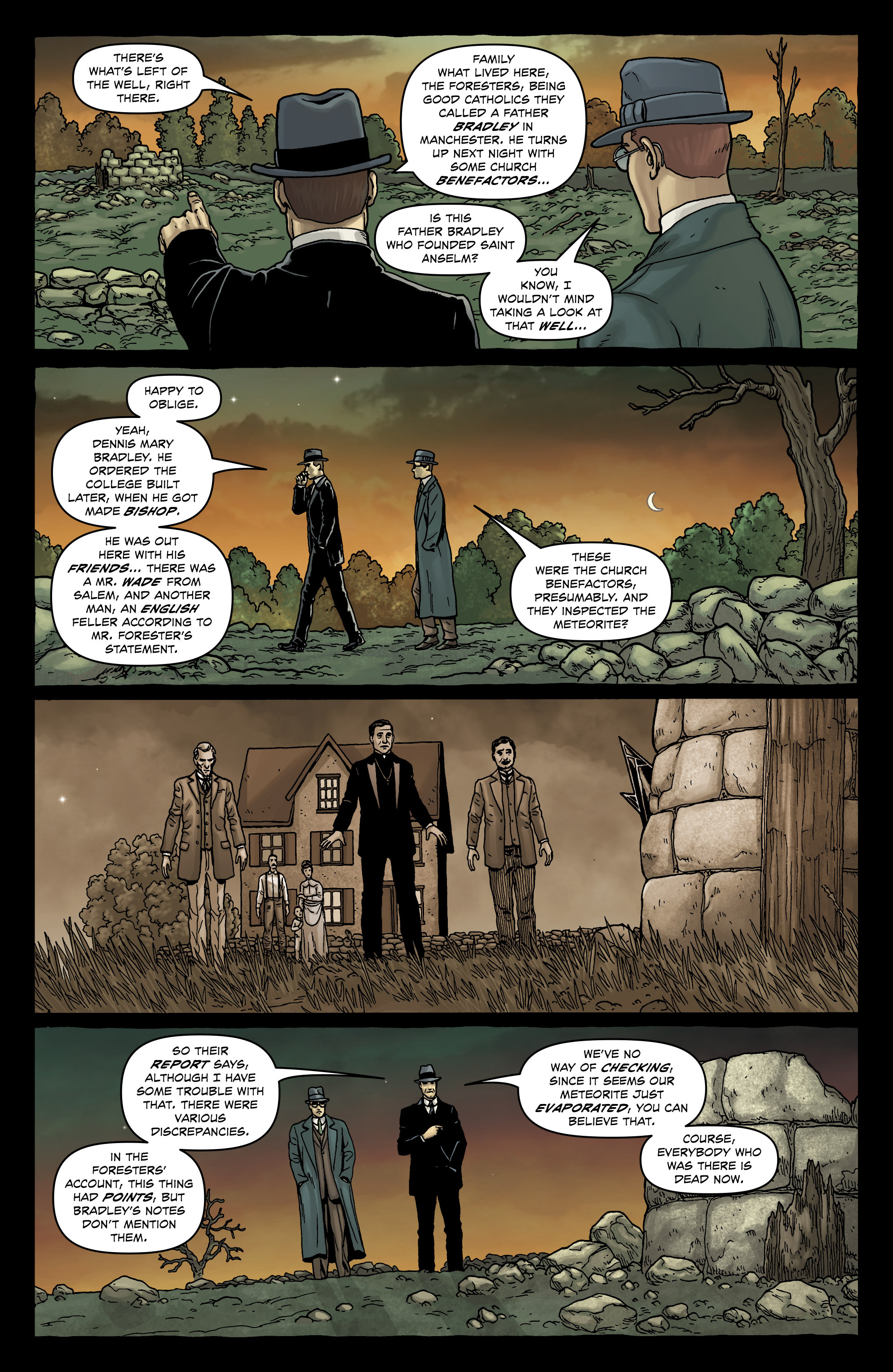

The scene above comes from a less than successful sequence in Providence #5 where Robert Black talks to Frank Stubbs at a meteorite crash site. Like many other parts of Providence, there is lengthy exposition through dialogue here with two figures talking and striding across a barren landscape, almost always equidistant from each other with the occasional reverse shot.

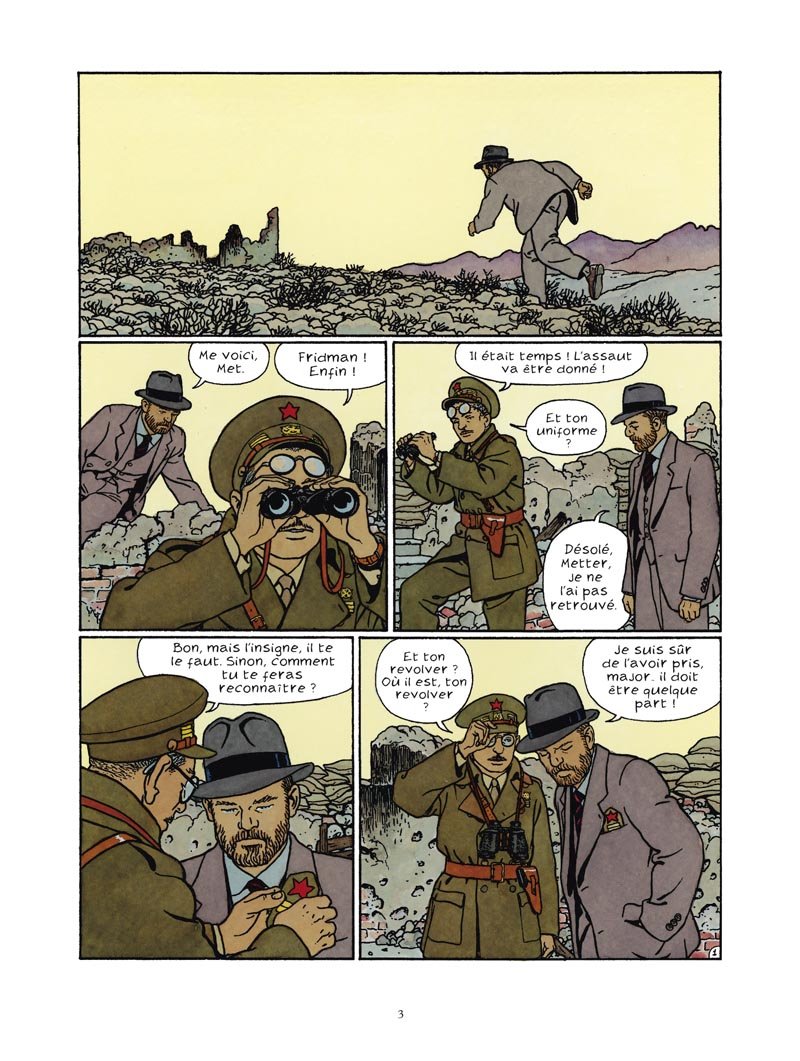

The foliage, background and foreground are unremarkable, the figures seem to pace forward like graceless stick figures wearing whalebone corsets, hands largely in their pockets and at their sides except for the odd stray cigarette hand; and it just seems like a very tired exercise in drawing, perhaps a combination of fatigue, boredom, and time pressure. We can see what a relatively old hand like Vittorio Giardino does with a similarly unremarkable sequence set in a barren landscape in the page below.

An unfair comparison perhaps because of the lack of expository dialogue (and the demands of the script) but also a useful one because of Giardino’s passion for naturalistic clean-clear lines. You might have qualms about the art, but at the very least, these people seem like human beings and their clothes lived in

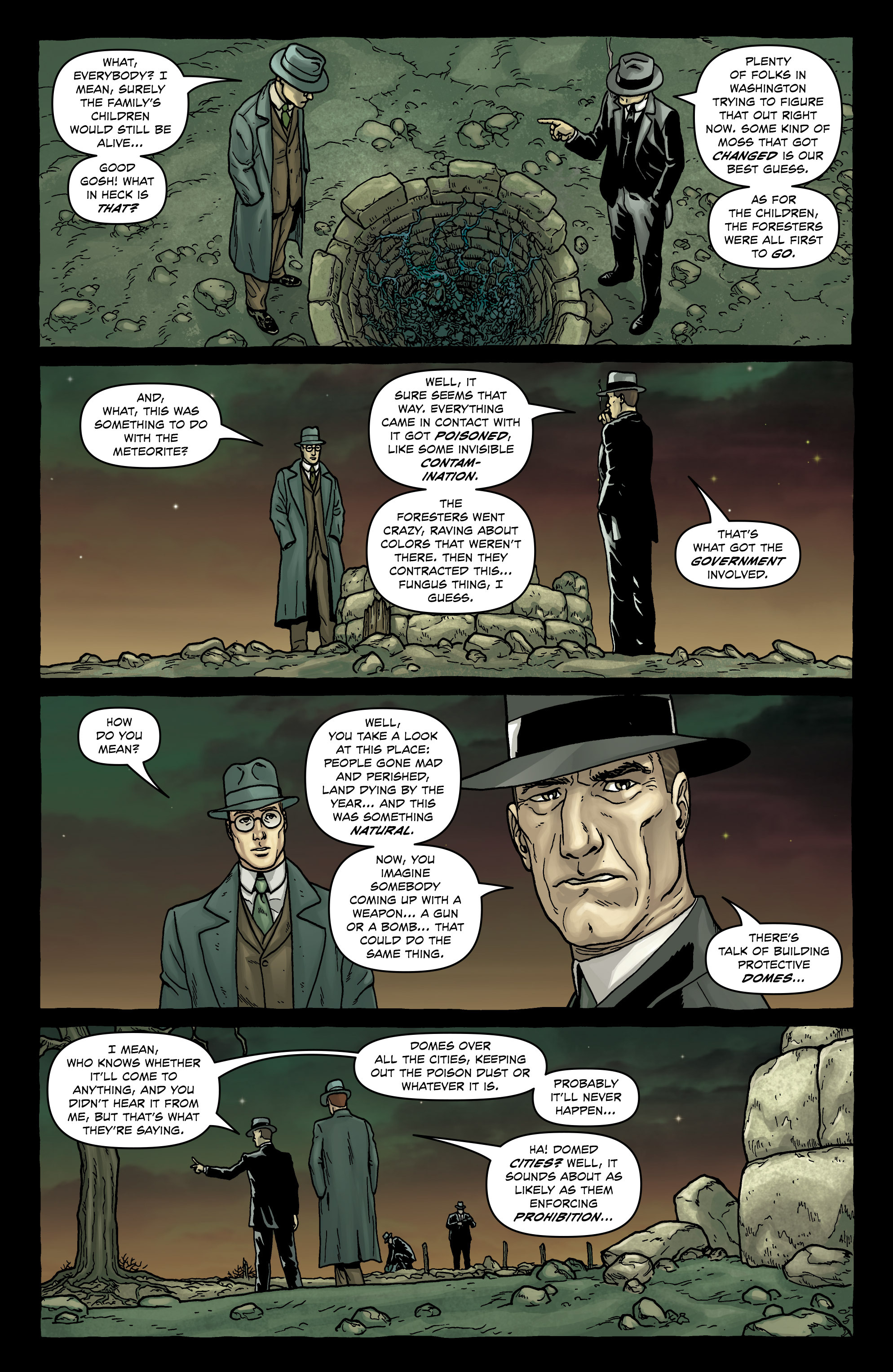

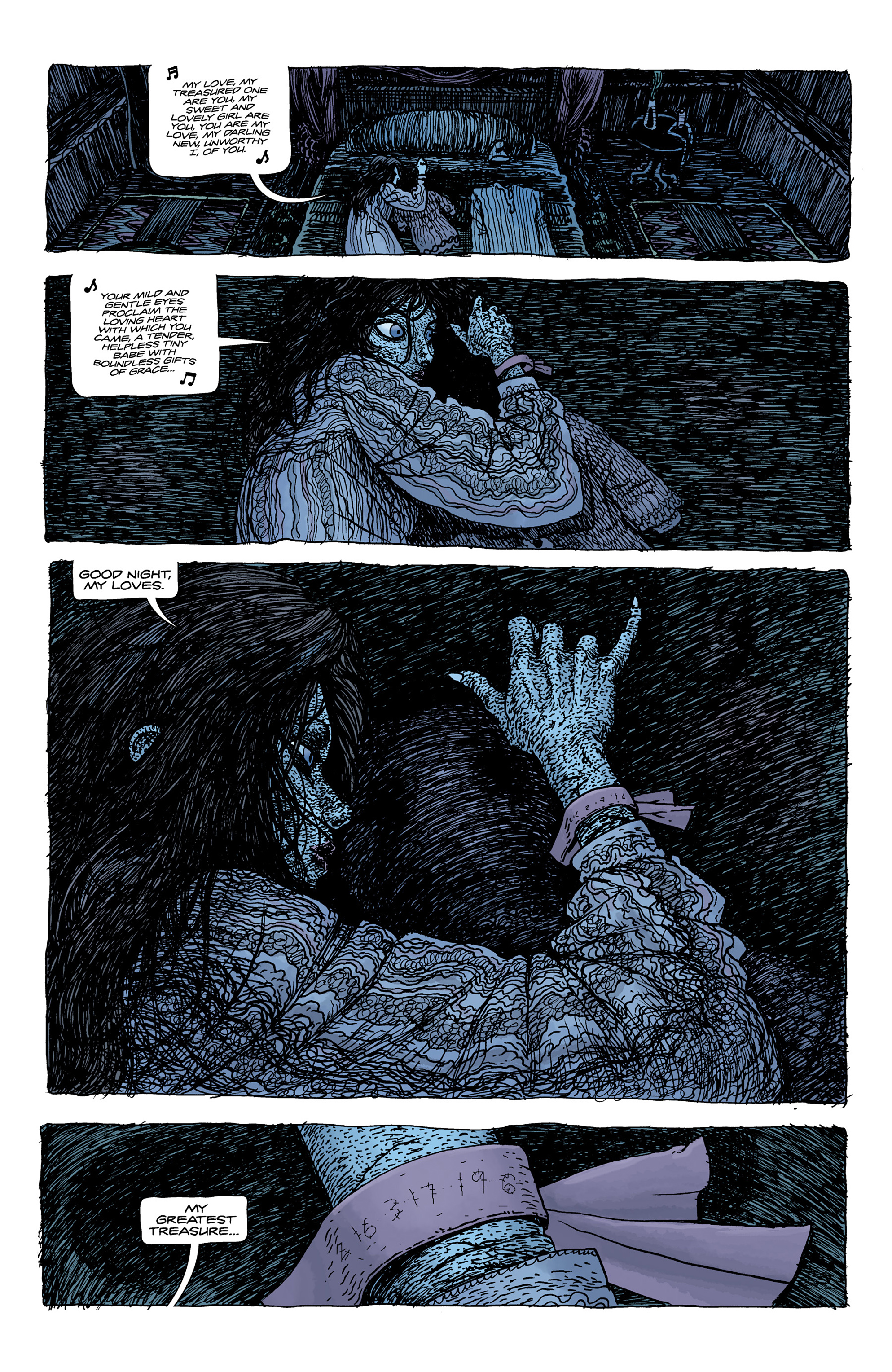

Burrows’ failure at such pedestrian scenes of everyday dialogue is in sharp contrast to an episode later in the same issue where a placid, bulbous hag sits comfortably breast feeding her familiar (Jenkins).

This almost seems to be drawn from nature when compared to many of the somewhat staid and geometric beings who otherwise inhabit Providence. Yes, the protagonist (Robert Black) doesn’t seem especially distressed as he puts on his clothes in a situation which would have most wetting themselves; he could just as easily be speaking to his wife after breakfast in bed. But Burrows’ feeling for the grotesque helps obscure his deficiencies in depicting the commonplace. One could almost make a case that the sheer tedium and falsity of the everyday images throughout Providence is exactly the point—the real world is the one we should be rejecting.

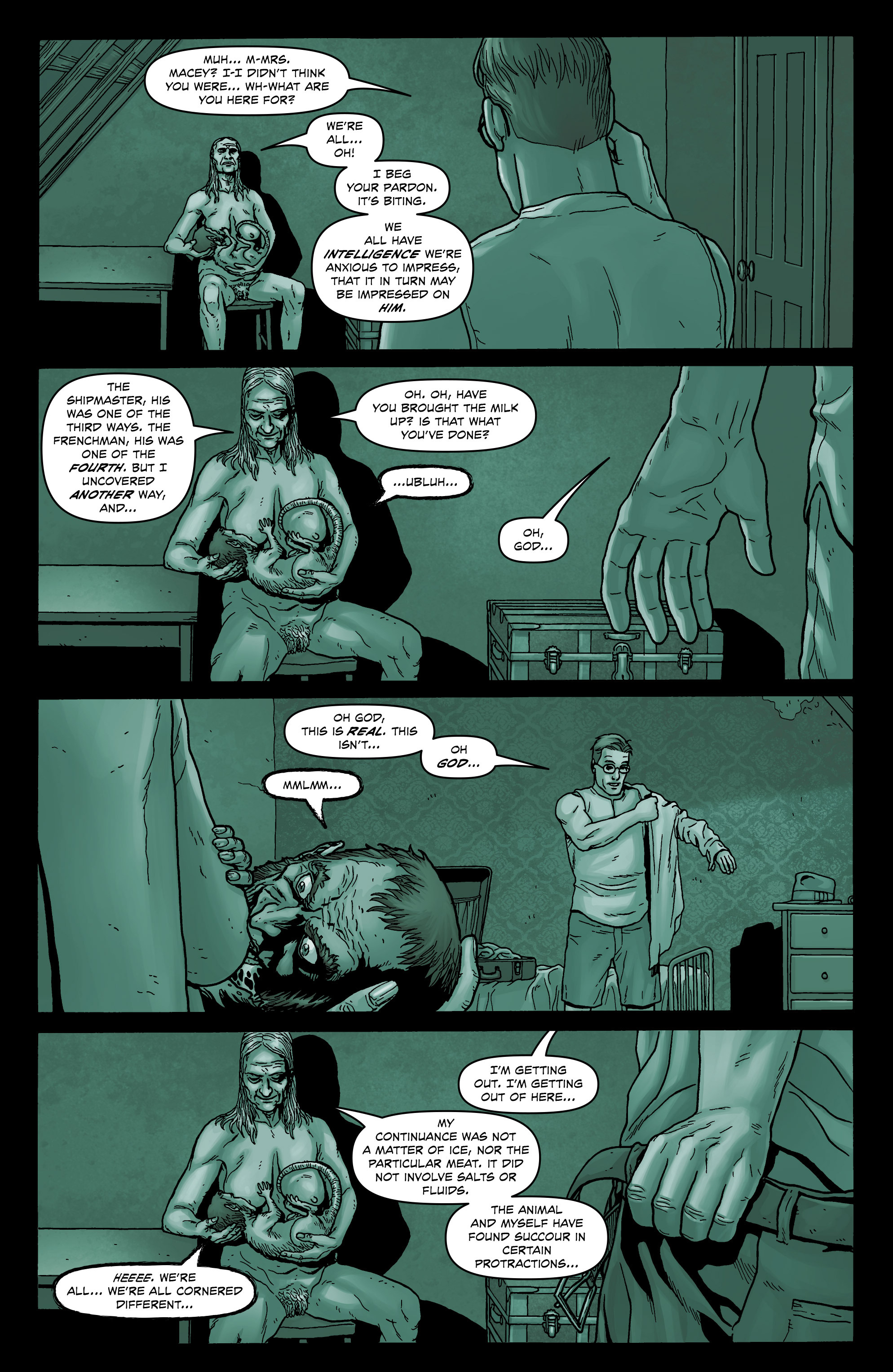

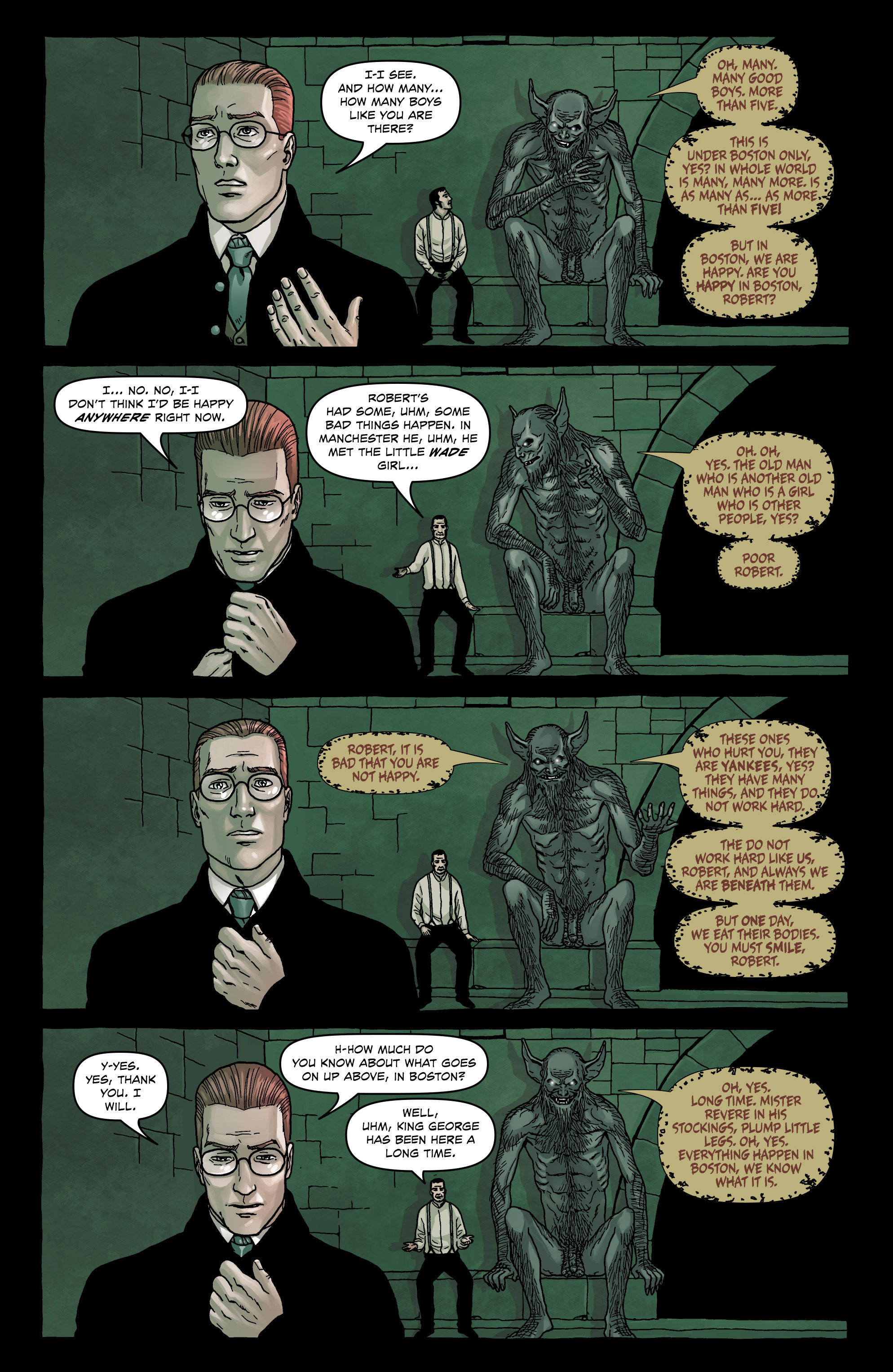

The six page sequence where Black encounters the ghoul King George shows a similar limitation in facial expression. The postures are once again unnatural and repetitive and the reactions of the protagonist fall far short of the requirements. For an encounter of such psychological terror, Black seems almost sphinx-like in parts.

The repetition in the perspective and background highlights a sort of anergia in Burrows’ line, a kind of disinterest in the psychological effects of lighting; the terror in this underworld is imperceptible and almost fully to be imagined by the reader.

Readers will also need to use their imaginations to determine what could have been in the alternative lives of a comic named Providence—the possibilities as you would expect are endless. In just the last month, a young artist by the name of Ian Bertram has shown what can be done to elevate a relatively sedate horror script in House of Penance.

But would the lack of photorealistic architecture affect our appreciation of Moore’s script and displace us from its everyday possibilities and ever present terrors? By the same token, would the dreams, fantasies, and terrors which haunt Providence’s North American underworld have been brought that much closer to us if we had someone other than Burrows to chart our course?

In the final analysis, it seems unlikely that Providence as a whole will attain the kind of status it probably deserves because of this weak link. If comics are to be seen as a truly collaborative process, then the wide disparity in achievement in Providence (between script and drawing) can often be ruinous if not quite tragic—a conductor and composer can only achieve so much with a tolerable orchestra. We can read the music and imagine its aborted pleasures but in comics, there will almost never be a second performance.

_____________

Addendum – Different Perspectives

(1) Craig Fischer writing at The Comics Journal has a few short thoughts on Burrows’ work:

“I’ve talked up Providence among other comics fans, their opinions of Jacen Burrows have been wildly different, with some liking his cool, architectural approach, and others sorry that his art lacks gonzo energy. (One friend wishes that the splash page of Leticia’s rape had looked more “like a mind-blowing combo of Steve Ditko, Rory Hayes, and Henry Darger” and less like an airline safety brochure.)”

(2) In the same vein, I asked a few of my own friends about Burrows art. First up is Domingos Isabelinho.

“…the art is stiff and the characters are lifeless, but what I can’t bear looking at is the computer coloring. It’s the worst thing that happened to comics ever, apart from the stupid stories, of course, but Alan Moore is never stupid. On the contrary, sometimes he’s too intelligent for his own good.”

(3) I also had an email exchange with a working cartoonist (henceforth known as Cartoonist Z) and here are a sampling of his remarks:

“Jacen’s style reminds me of Steve Dillon’s work. I think because his faces and expressions are reminiscent of Dillon, and with him also being tied to Garth Ennis (like Dillon) on whatever slightly grotesque stories come out of Avatar. For me, Dillon is the standard for ‘good’ comic book art in America (clear storytelling/consistent art) and I feel Jacen’s works falls just short of that Dillon quality.

What I particularly like about his work is it’s completely realized. Meaning it’s not phototraced or pulling inspiration from conflicting voices. It’s drawn in his hand, in his own voice. If you showed me a few images of this I’d know it instantly as “that guy who works for Avatar.” What I think he has improved on is at times his work can be stiff, but here I’m impressed with things like his hands, some lively expressions, and of course a gross lumpy body or two.

One thing that sometimes bothers me about his art, and I think holds him back as a clean line style/detail guy, is that his backgrounds can tend to be off. Not in reference and detail, but sometimes in the basic use of perspective. Clean line style doesn’t let you get away with those minor hiccups. Whereas someone working in a bit more ‘artsy’ style (think Sienkiewicz) can use suggested brush marks, artistic fades, crosshatching, splatter, and spot blacks for quicker backgrounds that are impressionistic (and have a lot of wiggle room to be technically off but still work in the context of their respective styles).

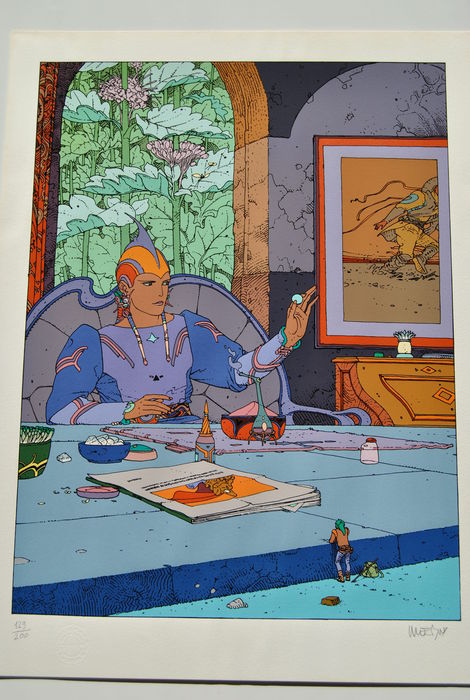

With Jacen’s clean line style, his use of perspective could stand to be tightened up. Examples of the very best working in this fashion are Moebius, Darrow, and Quitely. I can look at their work and use a ruler too learn perspective by finding the vanishing points and figuring out what they were thinking. Or simply just be mesmerized at their use of perspective, and how easily things exist and move within their environments. Jacen’s work isn’t at that level of skill yet.

Here’s some organic stuff I love, stuff that lets me know he has the potential to be really good. But for me right now his work feels like its good in spots.

Great face, eyes are alive.

Excellent expression for a small female figure.

Nice hands. His work tends to be a bit stiff (and hands are particularly difficult for all artists), so you’d expect his hands to be as such, but they are pretty organic and expressive.

Terrible. I know this is supposed to be a painting or whatever in the comic but it breaks the one big thing Jacen has going for his art—that consistent voice. I talk about this a lot with comic book making. You can read a great comic with stick figures as long as it’s drawn honestly and in the same voice.

It’s why a little kid’s drawing can resonate with you. It’s honest. Not in the romantic sense but in the mechanical sense. This painting in the middle of the comic is just an absolute turd. Terrible drawing. Terrible Photoshop coloring. It doesn’t fit in with the art whatsoever. As such, all of his flaws are amplified and made apparent. It just doesn’t work. I’d much rather Jacen draw the painting in his current style and just have the colorist color it slightly different. Or even color the same and color hold (lighten) the line art.

Notice how Moebius handles paintings and posters in environments. It’s all the same voice.

To better get across my point of his backgrounds being close but not exact. I picked a few things out to draw over.

On this page here, let’s look at panel four. I like the concept of the cuffed hands being in the foreground, but the figures in the background aren’t engaged in the scene. As of now they are too far back from the inmate (based on the established distance in panels 2 and 3). So to make the drawing ‘right’ (referring back to my earlier point that clean line style perspective needs to be exact), you’d have to put the inmate back into the shot (version A); or keep the great concept of the hands in the foreground, but actually move the camera down to the hands, moving the vanishing point lower and allowing the vanishing point to guide the rest of the drawing. The lowered vanishing point would mean more of an upshot on the officers in the mid ground (version B).

This allows for a much more engaging shot, really establishing a foreground, mid-ground and background, and creates all kinds of nice overlaps which creates the perception of depth. I also think, storytelling wise, the reader would feel the investigators urgency and get sucked to a greater extent into the story. I feel that Jacen’s work while clearly thought out in a storyboard type of way, can sometimes fall flat in the finish and not engage up to its full potential. In this sense, every so often an environment while referenced and detailed accurately can just feel ‘there’, and doesn’t feel 100% lived in. I hope this over draw brings a little bit of clarity to that point.”

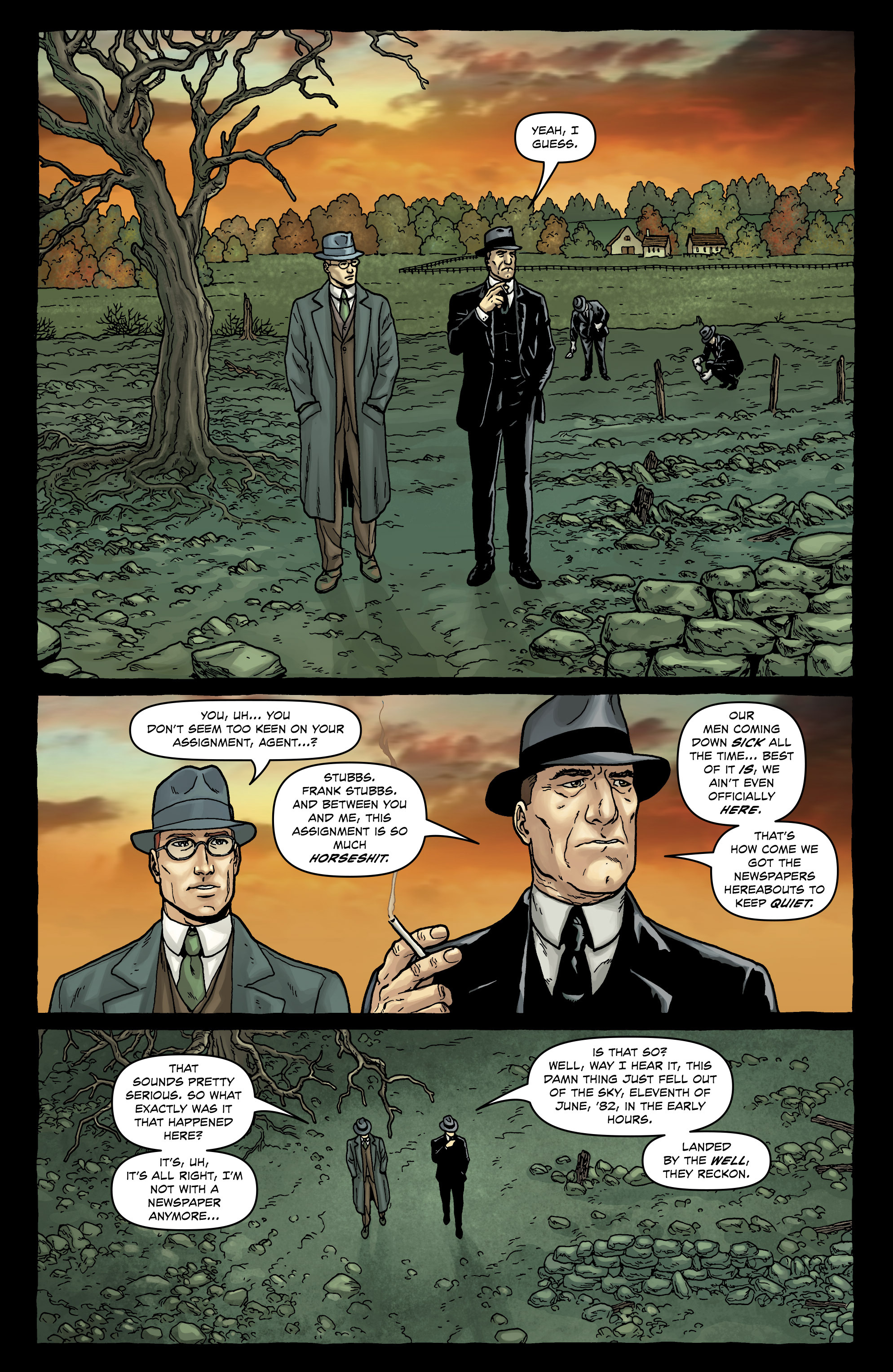

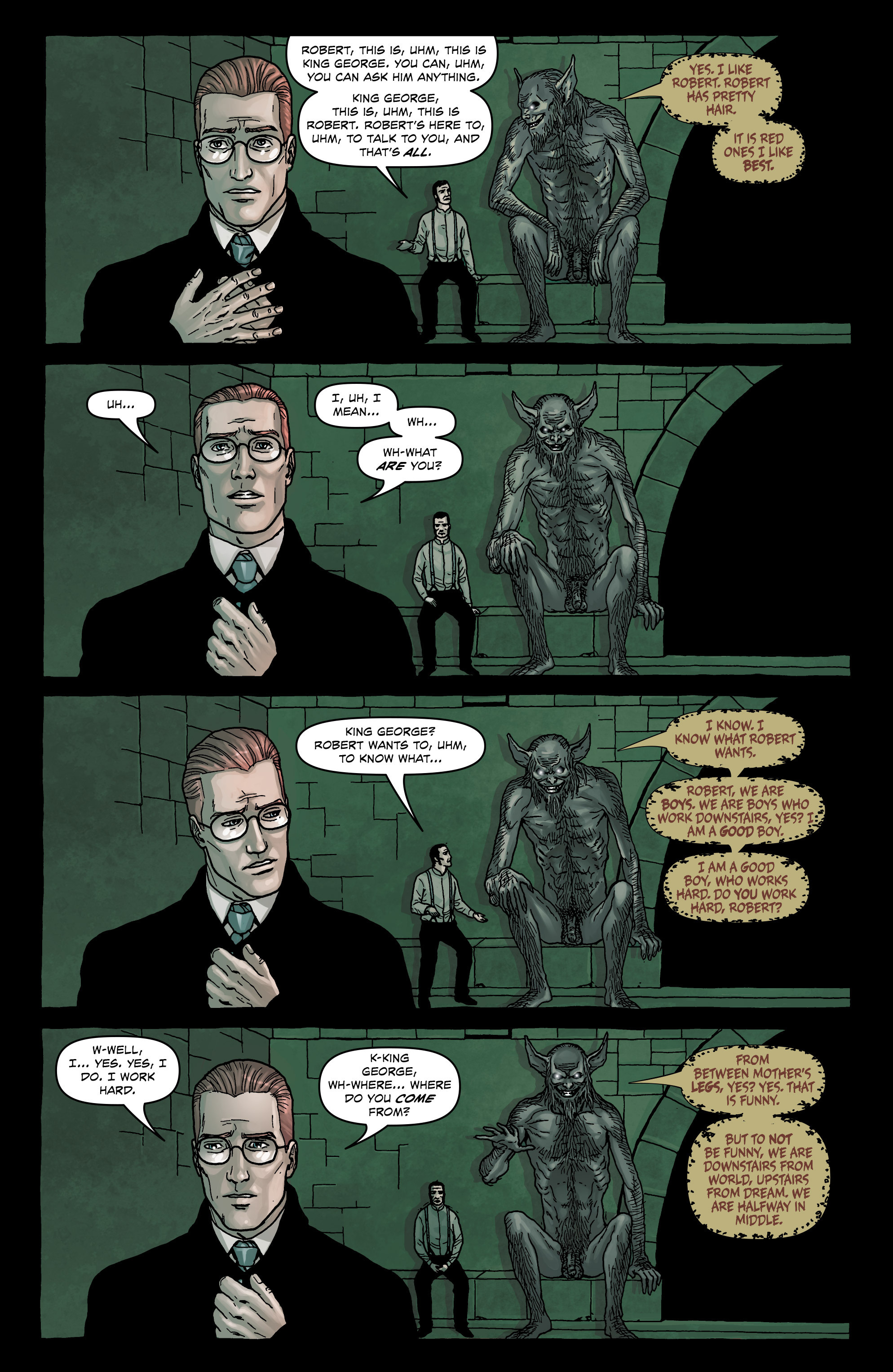

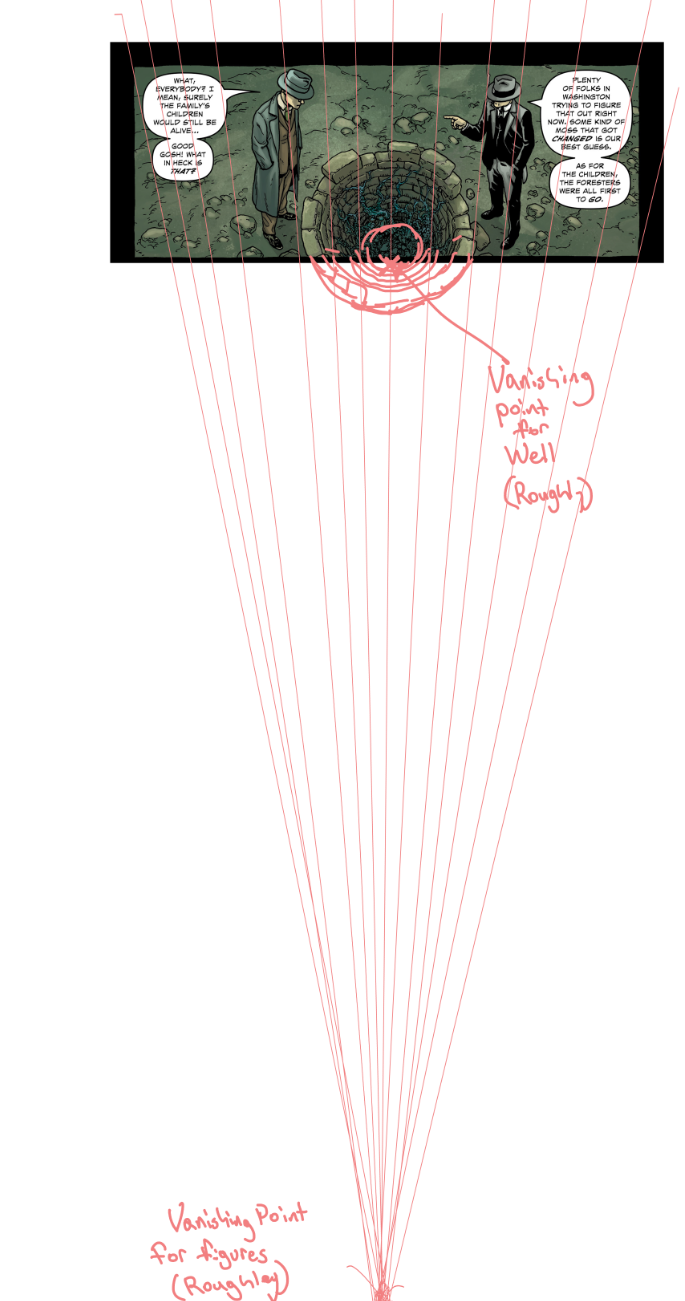

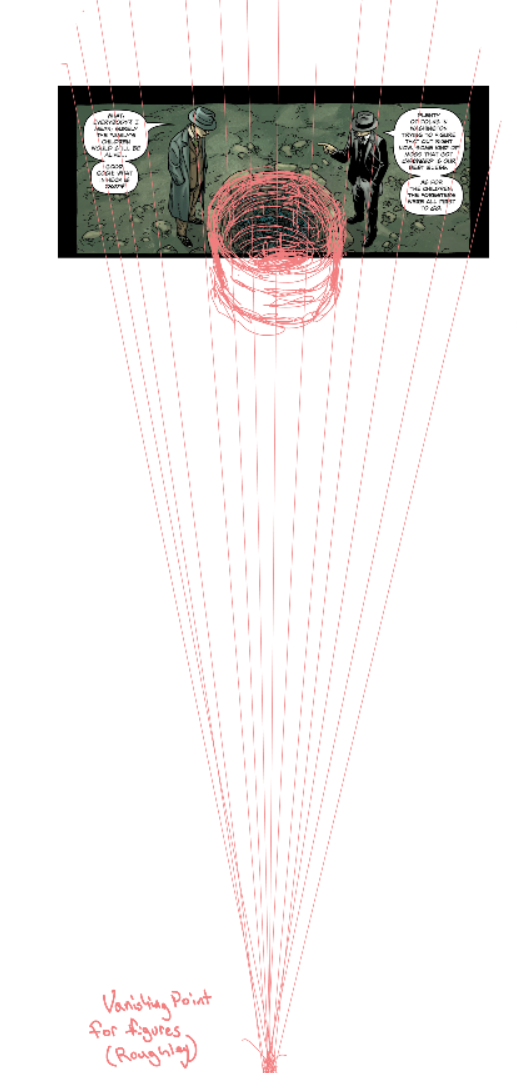

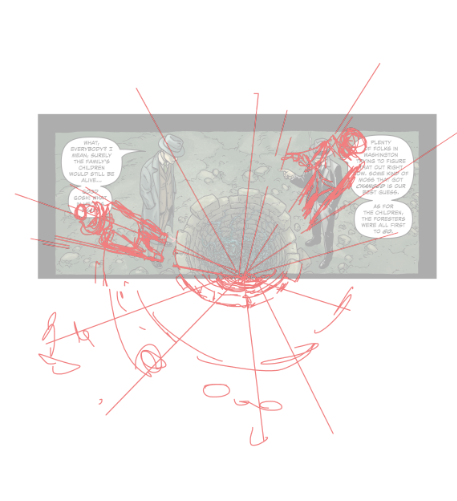

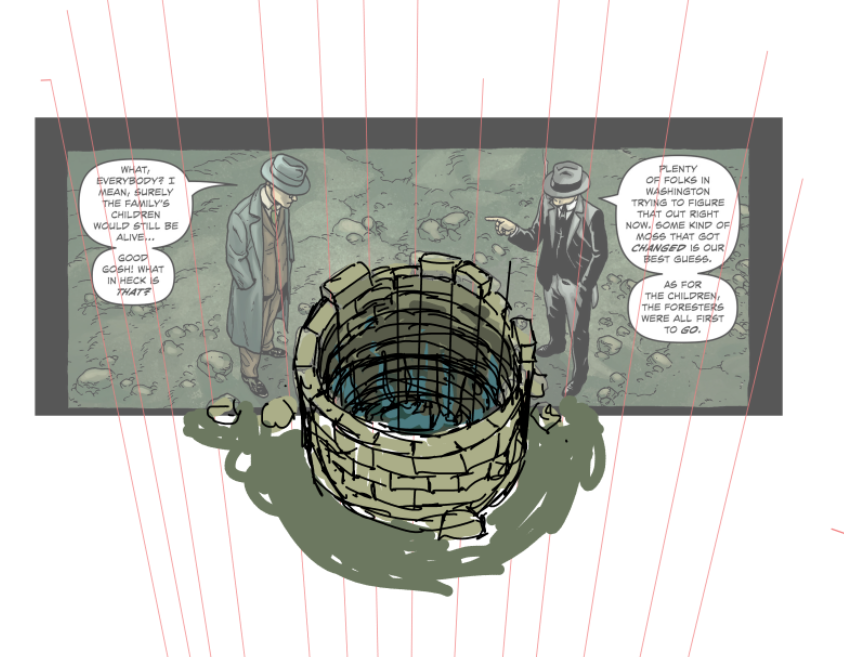

Let’s look at panel one of this page.

Mechanically speaking the perspective is off. The figures have a different vanishing point than the well. You would either have to pick the vanishing point for the well or for the figures, and that vanishing point must dictate all objects in the environment.

Here the well perspective is corrected to align with the figures.

It’d be tougher to align the figures with the well perspective at this point. A quick rough if we did correct it that way.

To correct what Jacen already has down I’d choose to handle it as such.

I believe with a little more care when it comes to the mechanical workings of perspective and environment drawing, Jacen would level up as an artist. I hope these over draws help clarify my perspective.”

(4) Jacen Burrows on his first experience working on an Alan Moore script (Neonomicon):

Bleeding Cool: Well, Alan’s famous for long involved script descriptions that at the end say “but if you have a better way, do that instead”. What changes, if any, did you make while working on the book?

JB: I haven’t made any that I can think of off hand. I pride myself on trying to get as close as I can to the writer’s vision. It’s kind of a game for me. I think I must have a little OCD buried in the back of my mind somewhere that this kind of thing triggers.

(5) Mahendra Singh on Jacen Burrows (added 27th May 2016)

Jacen’s Providence work is pretty much the current American corporate comix house-style for realism. He’s a younger artist and his draftsmanship and cropping (the latter is very important in his style) are indicative of this. They will improve over time although there is a potential to devolve into a slick, hack-style if he’s not self-aware. In short, he is a competent artist with a full set of competent skills but is still going through an apprentice phase. The flow of his panels and the on-off draftsmanship need improving but I suspect that he knows this. The worst thing he could do, if he wishes to do seriously good work, is continue drawing for fanboyish tastes. The inherent limitations and demands of this material are going to wreck him.

It’s the same old story: do work that pays and also destroys your talent or do work that no one cares about and that will allow you to become a real artist. Jacen is on the cusp of that decision. He can draw and he can tell a story, he needs to pull it all together by throwing off the shackles of this corporate style.