Ballet Scene from Meyerbeer’s Opera “Robert le diable”, 1876, oil on canvas, 76.6 x 81.3 cm.,

London, Victoria and Albert Museum

Last year’s Degas show at the Royal Academy in London was an eye-opener. Premised on an obvious idea that nevertheless has yet to be fully examined, it presented the artist’s work on subjects relating to the ballet with focus on contemporary interest in the understanding and truthful depiction of movement.

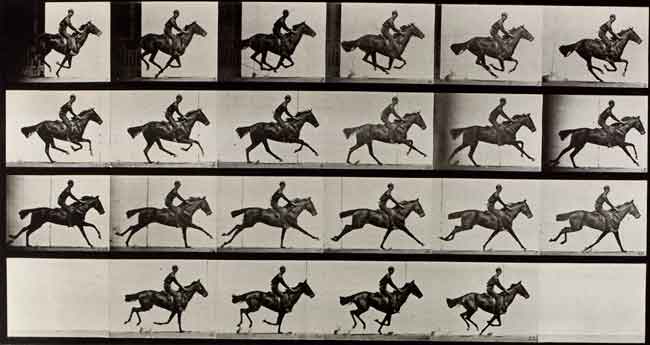

Juxtaposing Degas’ work in drawing, painting, sculpture, and photography with the photographic, cinematic, and sculptural studies of human and animal locomotion of Eadweard Muybridge, Étienne-Jules Marey, Paul Richer, and others, the exhibition made the case not so much for direct axes of influence (as the Burlington Magazine’s confused reviewer assumed, for instance), but rather of a general confluence of interest between them.

Conspicuously missing from the show, however, was one of the quintessential nineteenth-century forms dealing almost obsessively with the depiction of movement: comics. This is hardly surprising: despite the show’s progressive approach to the study of nineteenth-century art, we have unfortunately not yet reached a stage where the specific and highly charged connections between popular and high culture of the period are fully recognized.

Pointing fingers at an otherwise stellar show only goes so far, however. More interesting is how it laid bare new ways of understanding the language of comics as it developed in Degas’ time, and how its fresh perspective on his art, when seen from a comics standpoint, illuminate further the epistemological insights of his art.

As the show emphasized with a stunning display of pastels hung in the penultimate room, Degas was ever an artist in the grand tradition of the renaissance, fastening raw human experience in color, his dancers timelessly moving to the tune of history. The paragons are clear: Raphael, Titian, and Veronese, through Watteau and even Goya, all found in Degas a modern interpreter.

This, in part, is due to his investment in contemporary media and form—his boundary-challenging work in photography is but one example of this, while the exhibition suggested other parallels, one of which — a short fumetto in which Degas acted out a vaudeville skit with a couple of friends — touch directly upon the language of comics.

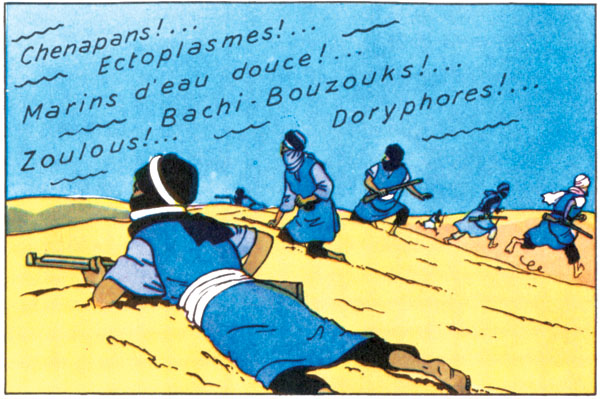

Years earlier, in his attentive depictions of stage performances, he touched initially upon sequentiality as a means of depicting movement, and more fundamentally conveying subjective experience. Not only is his Ballet Scene from Meyerbeer’s Opera “Robert le diable” of 1876 (see above) framed to suggest his particular point of view from the front stalls, it depicts in a brushy swathe the sensation dancing movement across the stage. Simultaneously a snapshot depiction of the large, costumed ensemble on stage and a suggestion of movement from back to front and left to right, it proposes a dynamic and novel solution to the centuries-old problem of conveying the passage of time in a single image. This strategy of employing individual figures to suggest a general pattern of movement was later employed to great effect in single panels of comics, most famously by Hergé in several of the Tintin books.

It would seem that such innovations developed from the old problem of how to represent the passage of time with one image. This has been essential to narrative picture-making since antiquity, but reached new levels of sophistication in the high renaissance when the single image became increasingly divorced from the narrative series of medieval and early renaissance art. How to suggest the before and after? How to pose a figure to indicate previous or future action? Acutely aware of this tradition, Degas crucially achieved a synthesis of this knowledge with the aesthetic of photography. His figures are often posed in ways only the mechanical eye of the camera could otherwise see, but are simultaneously tweaked to achieve the illusion of movement that is mostly absent from snapshot photography.

Left: preparation for an Inside Pirouette, c. 1880-1885,

charcoal and black crayon on paper, 336 x 227 mm., Belgrade, National Museum;

Right: Dancer (Préparation en dedans), c. 1880-85,

charcoal with stumping on butt paper, 336 x 227 mm., Trinity House

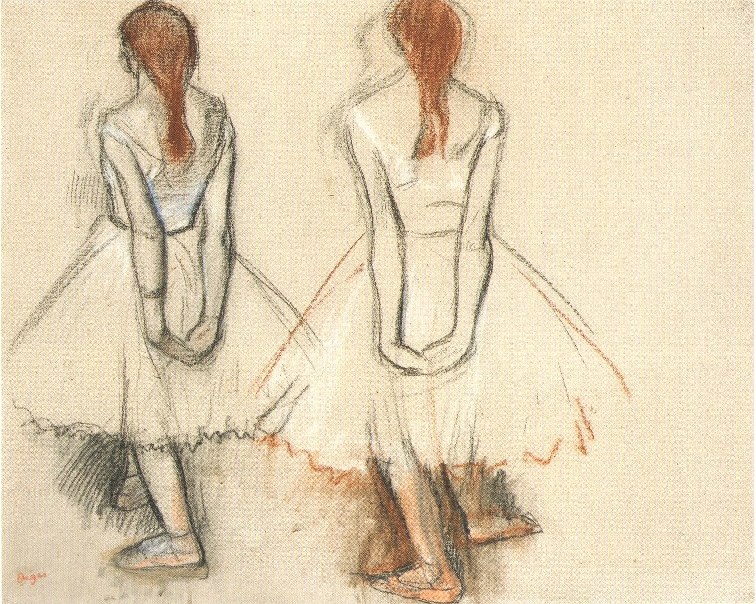

This is evident from his astonishing on-the-spot sketches of ballerinas practicing from the 1880s. Drawn in something approaching real-time, the artist’s hand following the motion of his model, these sketches are fundamentally different from the sequential, or chronophotographical experiments of Marey and Muybridge along with which they were displayed in the exhibition. Although their ambitions are similar, the photographers achieve the illusion of movement through juxtaposition of individual photos frozen in time, whereas Degas’ knowledge of temporal illusion conveys an almost bodily sensation of the movement suggested.

In one sketch, the dancer torques her body in preparation, motion lines of the kind later so familiar to comics readers conveying the movement of her right arm, and judiciously applied vertical hatching between her feet helping further to suggest the determined circle she is beginning to describe. Another sketch conveys vigorously the imminent discharge before a pirouette. By drawing his models in positions tweaked beyond the anatomically possible and energizing them through motion blur, Degas achieves an effect of action-through-time impossible in photography.

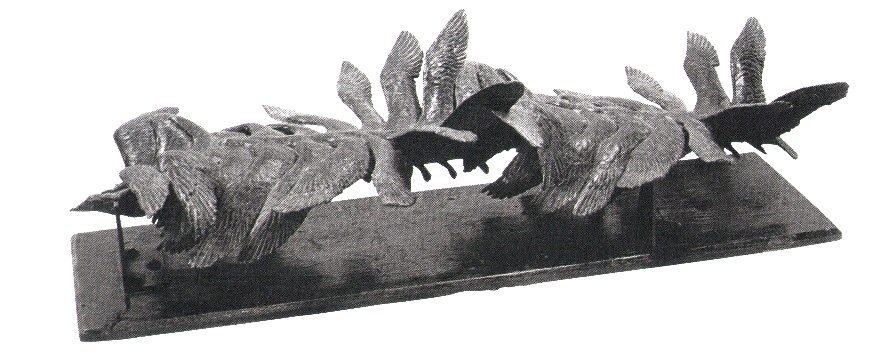

In the same room, Marey’s fascinating sculptural renditions of birds in flight — transposed from photography, fusing duration in bronze — were shown alongside Degas’ bronze studies of female nudes in motion, well-known but rarely arranged as they were here, sequentially performing three steps of the grande arabesque. The connection to comics is apparent, and it would have made sense to place the similar experiments by contemporary cartoonists of combining narrative single drawing with sequence to describe movement and action.

Grand arabesque: First, Second and Third Time, c. 1885-90, bronze, 48.5 x 24 x 34.5/ 42.6 x 29.2 x 61.2/ 43.2 x 33 x 50.8 cm., Glasgow City Council/ Sterling and Francine Clark Institute/ Norton Simon Art Foundation

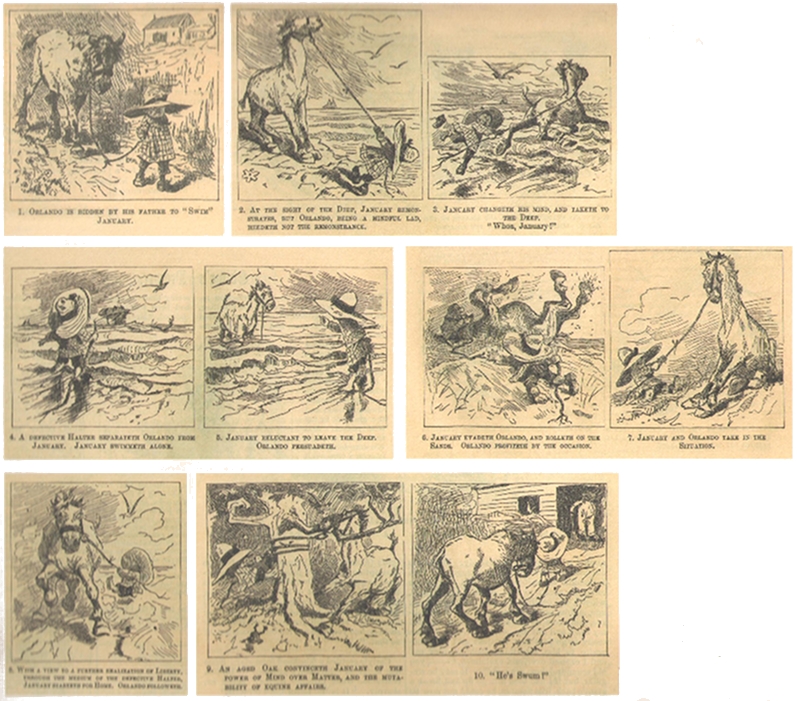

Among the most accomplished in this respect is the American cartoonist A. B. Frost. Immediately attentive to the discoveries of chronophotography, he lampooned it in his early 1880s cartoons. But as Thierry Smolderen has shown us he also learned from it in a way that helped transform the sequential grammar of comics.

The natural movements of a horse in motion became the occasion for visual comedy, but the subtlety of a body’s motion moment-to-moment also opened cartoonist’s eyes to the narrative potential therein, resulting in sequences with only minor but no less crucial changes from panel to panel—something that would have been unthinkable earlier, not the least because the laborious wood-engraving process necessary for printing the comics generated an imperative for variety.

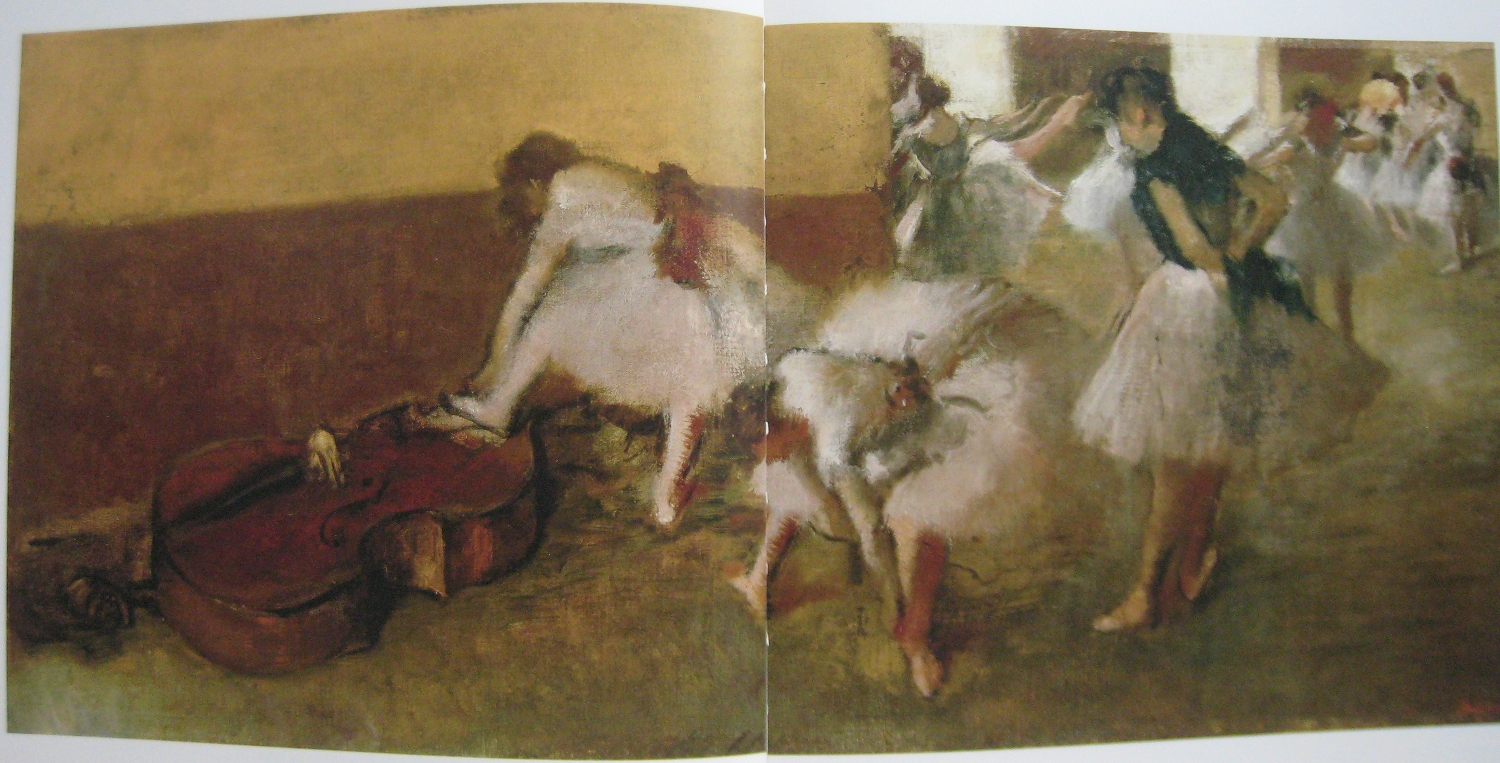

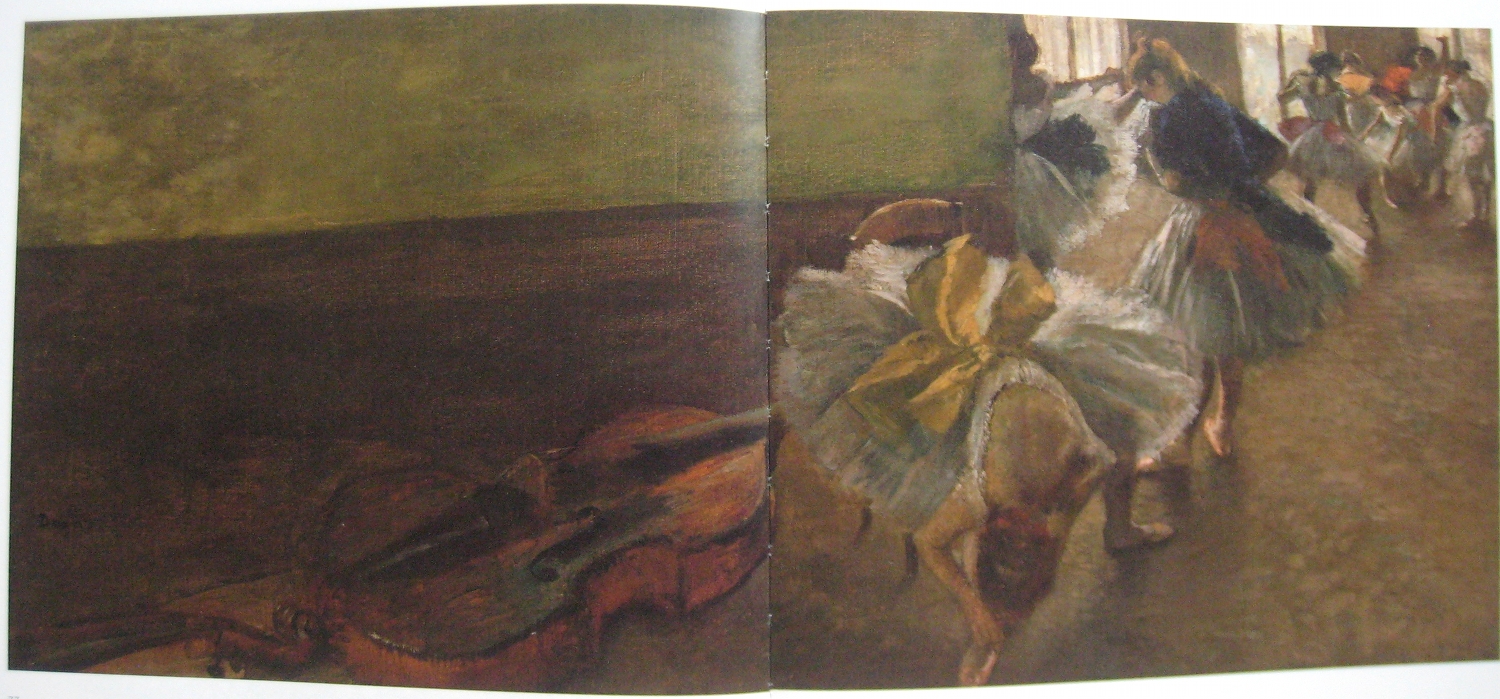

Surely these discoveries also inform Degas’ series of widescreen rehearsal studio interiors. Degas painted almost a dozen of these canvases over a period of around twenty-five years, all set in roughly the same space — initially adapted from a real dance studio, but clearly turned into a malleable architectural framework for him to experiment with. The exhibition presented five of these works, proposing a link to the contemporary vogue for the panorama, but it seems more appropriate to understand them, again, in terms of representing movement, or perhaps rather time.

Dancers in the Rehearsal Room with a Double Bass, c. 1882-85, oil on canvas, 39.1 x 89.5 cm., New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art

Dancers in the Foyer, c. 1889-1905, oil on canvas, 41.5 x 92 cm., Zurich, Fondation E.G. Bührle Collection

Panoramas may have provided Degas with his unusual formatting, but his clearly articulated, subjective point of view is far from the Archimedean ambitions of that form. Having been executed over such a long stretch of time, it was certainly not a tightly planned series, but when taken together they nevertheless represent inspiringly the passage of time on several levels. A profound take on the impressionist penchant for series, Degas here paints the years passing. Seasons change with the light while his brush technique expands and flowers, achieving heightened tactility and depth of glow. The figures are animated initially through snapshot posture and motion blur, but later also through the dynamic pulse of their loosened outline. These young dancers flick through the space in a way akin to fast-motion in film — and of course to the by now commonplace technique in comics of setting action against a fixed backdrop, panel-to-panel.

From “A Clockwork Orange”, directed by Stanley Kubrick (1971)

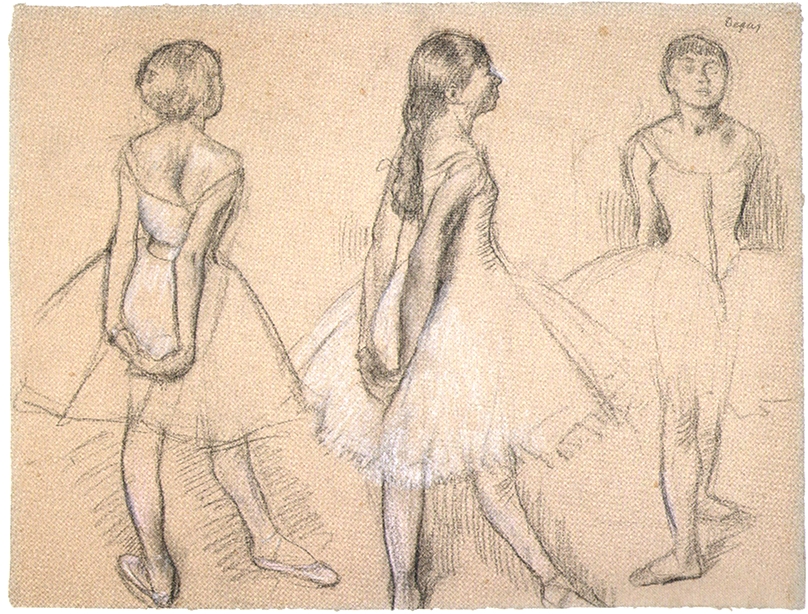

The conceptual set piece of the exhibition, however, was no doubt the display of sketches for Degas’ most famous sculpture, the Little Dancer Aged Fourteen (c. 1922). In preparation for the work, Degas made a 360-degree survey of his model. Juxtaposed, these drawings form a number of broken sequences conveying the sense of circling the little dancer, again and again. Of course, artists had made studies from multiple angles before, but it is the systematic approach — similar finish, same distance to the subject, the sheer number of sketches — that gives this series of sketches its temporal character. It is not just about seeing in the round, but about the locomotive, bodily way we experience the world, forming our impression from a multitude of fragments processed in time.

Three Studies of a Dancer, c. 1878-81, black chalk with white heightening on pink paper, 470 x 623 mm., New York, Morgan Library

Two Studies of a Dancer, 1878-79, charcoal, pastel, and wash on paper, 472 x 585 mm., private collection

There is something fundamental to Degas inquiry into time and space as articulated by movement here. The show suggested how he reached these insights by situating him in a context obsessed with inquiry into these phenomena, as someone who by virtue of his classic orientation and unique eye was able to probe their epistemological significance. It has become almost common knowledge how early nineteenth-century pictorial arts anticipated photography, and it is evident how photographic and other pictorial techniques and approaches, such as those practiced by Degas, anticipated film. What remains unacknowledged, and as mentioned was entirely ignored by the curators here, is to what extent the same phenomena were explored in comics, a medium in which Degas can be said to have worked with as great sophistication and insight as anybody else in comics history.

Edgar Degas and the Ballet: Picturing Movement was shown at the Royal Academy, London, September 17–December 11, 2011. Catalogue by Richard Kendall and Jill Devonyar, London, Royal Academy of Art, 2011. The paragraphs on Frost are heavily indebted to Thierry Smolderen’s eye-opening book, Naissances de la bande dessinée (Brussels: Les Impressions nouvelles, 2009).