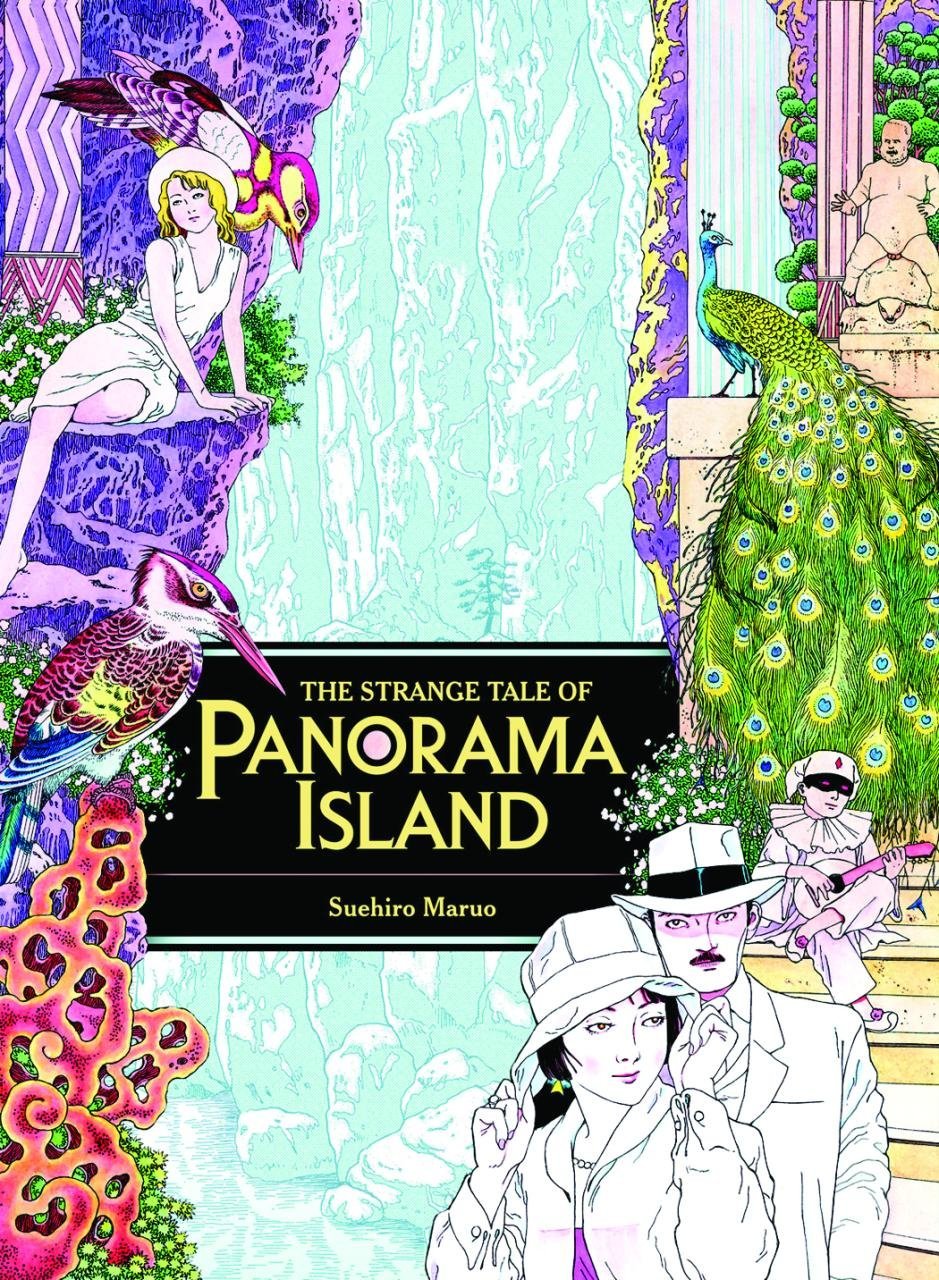

A review of Suehiro Maruo’s adaptation of Edogawa Ranpo’s The Strange Tale of Panorama Island

Synopsis (spoilers throughout)

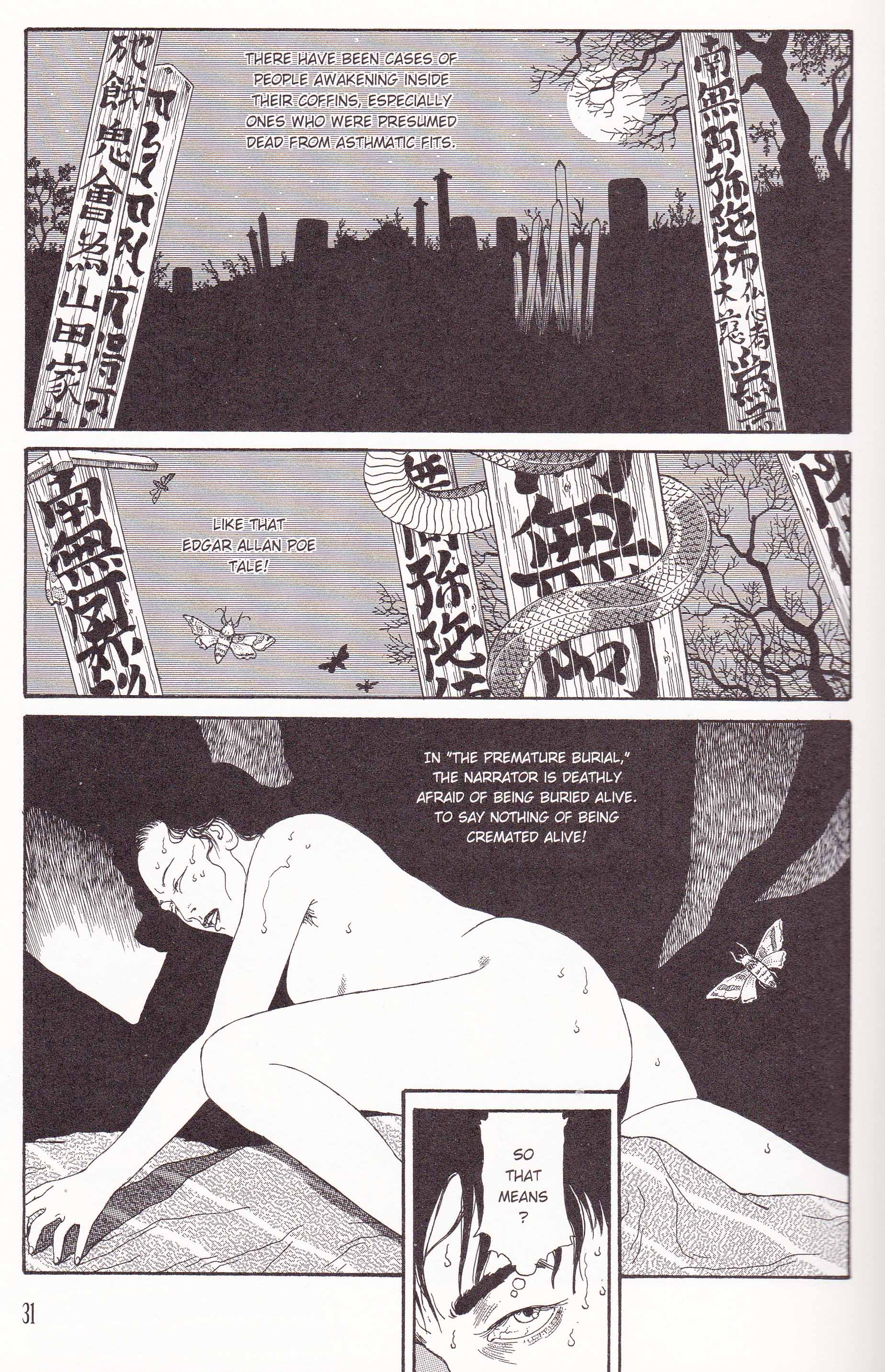

An unsuccessful author named, Hitomi Hirosuke, has visions of creating the ultimate work of art, a Utopian panorama of existence. He hatches a plan to impersonate a university friend (a millionaire named Genzaburo Kodoma) who is not only his physical twin but who has also recently expired due to a seizure (epileptic in the novella, asthmatic in the manga). Hirosuke first feigns his own suicide, then digs up his friend’s grave, disposes of the corpse, and presents himself as a risen victim of an unintended live burial (he is initially mute in the novel but is completely articulate in the manga).

Over the next few months, he manages to seize control of the Kodoma empire and initiates his plan to build his Utopian society—Panorama Island. The only person who suspects his dissemblance is his wife, Chiyoko. He is drawn to her but also finds her unworthy of his attentions (and possibly dangerous) in view of his greater project. He soon decides that he must kill her. Hirosuke arranges for them to travel to the island when it is near completion, and in an extended passage presents her with its wonders. Torn between the life of vulgarity and excess he has created and his strange attraction to Chiyoko, he finally strangles her and buries her remains on an island resembling Böcklin’s Isle of the Dead (a concrete cylinder in the novella). He hides her disappearance and continues a decadent life style on the island, exhausting the Kodoma fortune before finally being confronted with his misdeeds.

* * *

Suehiro Maruo has long been held to be one of the masters of the Japanese “underground” ever since his introduction to American audiences in Comics Underground Japan (ed. Kevin Quigely). His “Planet of the Jap” from that collection is a violently ironic tale of the Japanese conquest of the United States. Propagandistic slogans (lifted from educational songs) proclaiming the superiority of the Japanese race are presented alongside images showing the brutalization of American women. In his compendium of ero-guro tales, Ultra-Gash Inferno, Maruo offers depravity as the only solace for humanity.

We find these aspects of Maruo’s artistry straining for release in all corners of The Strange Tale of Panorama Island (1926-27). The manga is an adaptation of Edogawa Ranpo’s novella of the same name. Ranpo (the pseudonym of Hirai Taro) was one of the key figures in Japanese mystery fiction but his novella (recently released in a new English translation by Elaine Kazu Gerbert) is less concerned with crime then with modern mechanistic entertainments (the panorama and the cinema), the siren call of art, and the obscene depths of the human soul. Ripe ground then for Maruo and not for the first time. His story, “Putrid Night” (1981, collected in Ultra-Gash Inferno) is clearly a bestial homage to Ranpo’s famous anti-war story, “The Caterpillar” (1929). The story concerns a quadruple amputee (“a large , living parcel wrapped in silken kimono”) tended to by his long suffering wife. Not only does the text deny (with a kind of black humor) anything to do with the glory and honor of war but, for the purposes of this review and as a reflection of a common theme which will soon become clear, Ranpo writes the following concerning the wife:

“…like two animals in a caged in a zoo, they pursued their lonely existence…her crippled husband’s greed had infected her own character to the point where she too had become extremely avaricious…[she] also managed to find a secondary source of pleasure in tormenting this helpless creature whenever she felt like it. Cruel? Yes! But it was fun—great fun!”

As with the short homage by Maruo, it should be made clear that the manga being reviewed isn’t a completely faithful transcription of Ranpo’s Panorama Island. In many ways, it is a rather different object. Certainly the sequence of events and the skeleton of the plot remain largely intact but there is a distinct difference in emphasis between manga and novella. Read in isolation, the manga overwhelms with its Caligulan decadence and florid imagery. Read alongside the prose work, it shows a preference for narration and wonder over psychological and philosophical depth.

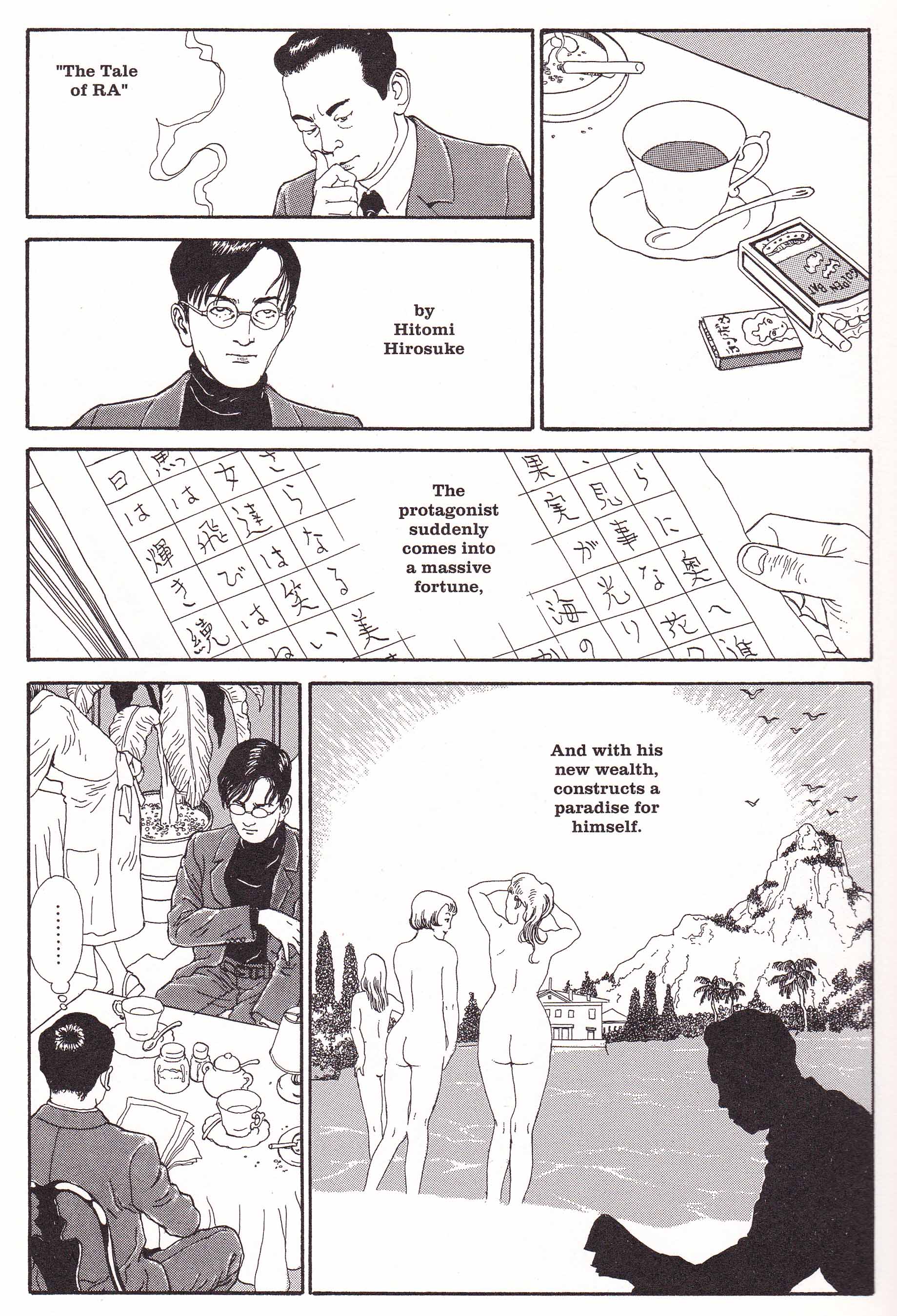

The dream sequence which opens the manga sees Hitomi Hirosuke imagining the strange vistas that will fill his novel, “The Story of RA,” and eventually his creations on Panorama Island. The manuscript which ensues is submitted to an editor and the conversation he has with him replaces the internal monologue which fills the first part of the novella. The stuff of captions not being much in favor in manga publishing, the internal musings and meanderings of the protagonist’s mind in Ranpo’s prose are largely made flesh through conversation and suggestion in the manga.

This alteration plays down the deus ex mechina ending of the prose work where the protagonist is confronted by a manuscript and an editor-detective which the readers have not hitherto been apprised of. In fact, Hitomic Hirosuke’s surprise at being confronted with “The Story of RA” at the end of the novella is as absolute as the reader’s. Ranpo submits this final chapter—this unwinding of deception and evil—with an air of knowing and fatalistic resignation:

“Reader should we here announce the happy ending of this fairy tale? Could Genzaburo Komoda, who was actually Hitomi Hirosuke, continue to immerse himself in the pleasures of this extraordinary land of panorama like this until he was one hundred year old? No, no, not at all. After all, it’s the pattern of in old-fashioned tales that right after the climax an intruder bearing a “catastrophe” is always on hand.”

As Gerbert (Ranpo’s translator) explains, this has everything to do with Ranpo’s predilections—his fascination with the kineoramas of time past and his desire to recreate these childish amusements:

“… a taste for playacting and theater animates [Ranpo’s] stories. They are often presented as if on a stage, with a dramatic buildup leading to a surprise ending that is presented abruptly, as if to the clatter of wooden stage clappers signaling the finale of a show.”

The dream sequence which opens the manga also makes flesh the mysteries with which Ranpo will later titilate his readers. One might say it almost circumvents the awe readers are meant to feel as Hirosuke (disguised as Genzaburo) leads his wife through the nearly finished island of his dreams; this surprise being a part of that darkened space before entering a room filled with the panoramas Ranpo is recreating, a form of entertainment which reached its height in the early 19th century in Japan—a tradition re-enacted today in movie theaters and amusements parks throughout the world.

This final unveiling of the villain seems almost a secondary concern, as is the actual construction of Panorama Island which Ranpo dismisses in the course of a single paragraph:

“Thus a whole year of struggle in every sense went by. To speed up the telling of this story, I’ll leave it to you readers to imagine the troubles Hirosuke experienced…[ ]…I’ll just say that in the face of the power of money the word ‘impossible’ does not exist, and leave it at that.”

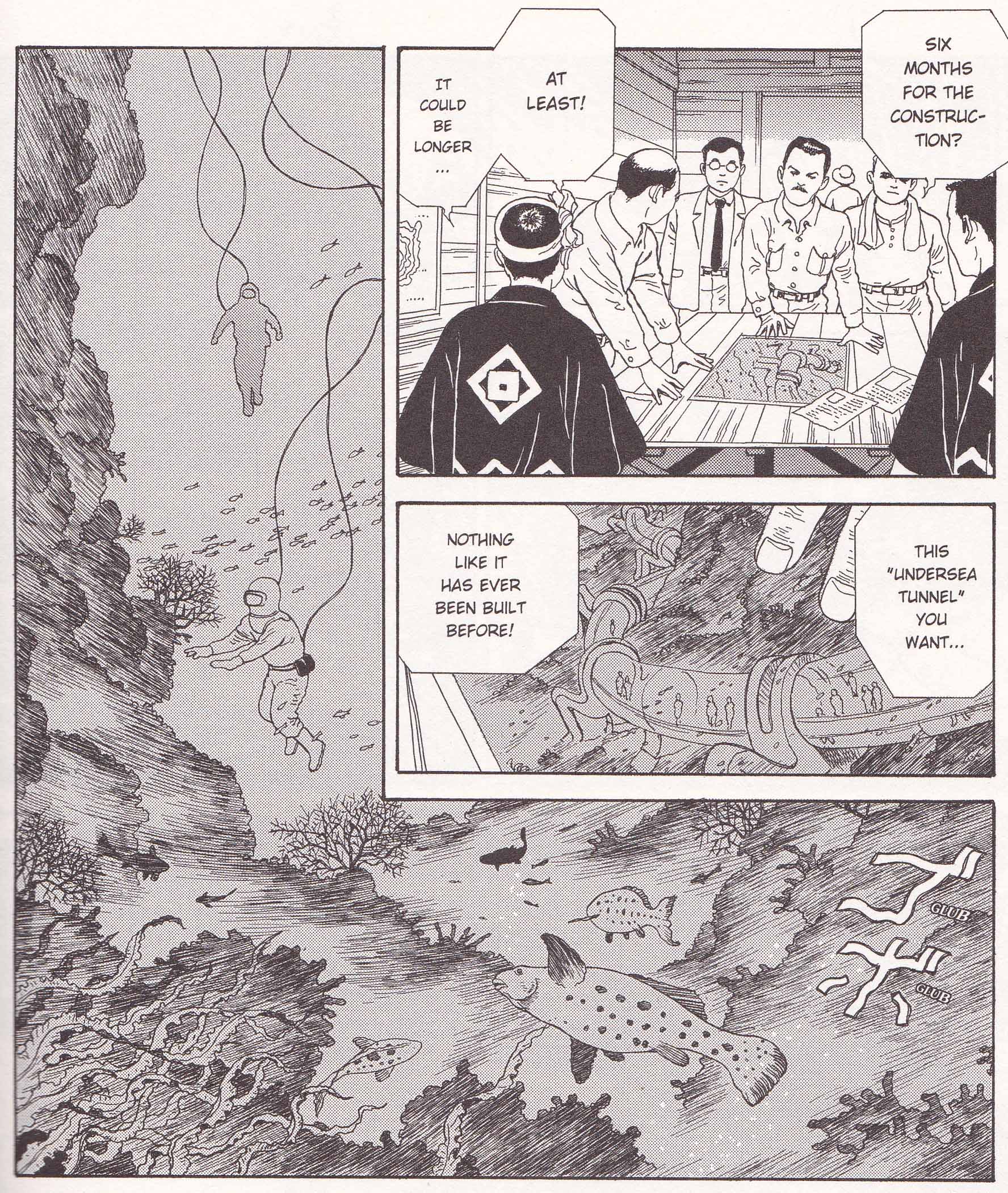

This may have been a side effect of the stories original serialization but this giant ellipsis is filled up quite thoroughly by Maruo in imagined scenes of construction and the hiring of specific workers for the island amusement. In so doing, the narrative threads are closed tight, the act of creation emphasized over psychological intensity and dread.

“…no such combination of scenery exists in nature as the painter of genius may produce. No such paradises are to be found in reality as have glowed on the canvas of Claude. In the most enchanting of natural landscapes, there will always be found a defect or an excess- many excesses and defects. While the component parts may defy, individually, the highest skill of the artist, the arrangement of these parts will always be susceptible of improvement.”

The Domain of Arnheim (1846) by Edgar Allan Poe

In the novella, the author is almost at pains to reveal the antecedents of his work; not only Edgar Allen Poe’s “The Domain of Arnheim” which provides inspiration for the descriptive flourishes in the work but also the Utopias imagined by writers and artists over the centuries; societies which have not only been expressions of human yearning but an unguarded divulgement of the creator’s ethics and desires. These utopias have rarely been places of “ideal perfection“, all too often embodying the stuff of nightmares. The only correct modern reaction befitting Thomas Moore’s “first” Utopia might be one of horror and perhaps recognition for it was a state of slavery, territorial confinement, and unapologetic expansion as dictated by the purely selfish motives of population growth and the aura of superiority of its leaders.

As Gerbert tells us in her introduction, the protagonist’s own name (Hitomi Hirosuke) is a play on the Japanese characters meaning “person” (hito) and “see” (mi) as well as “wide” (hiro). This is a counterpart to the meaningful names given by Moore to his characters in Utopia. In fact, the first fifth of the novella dwells extensively on Hirosuke’s tortured idealism, a burnished twin of his final descent into iniquity. Manchuria (latter day Korea) was just such a dreamworld brimming with promise—an undiscovered country conquered, colonized, and transformed following the First Sino-Japanese War. Gerbert notes the public fascination with that land at the time of the work’s serialization:

“Ranpo, in his novella, transformed the expansionist vision of Manchuria into a literal panorama spectacle, complete with a ‘gory battle frightening to behold.’ As few other Japanese writers managed to do, he conveyed the way in which mechanized visions of the twentieth century fed dreams of greatness, and how those dreams might lead to destruction and death.”

The most famous Panorama–kan was located in Asakusa and destroyed in the Great Kanto Earthquake of 1923. In The Edogawa Rampo Reader, Seth Jacobwitz describes Asakusa as:

“…a famously disreputable and squalid place even before the hard economic times brought on by Japan’s increased militarism and the Great Depression…for Rampo these were not only locales where tradition butted up against modernity, or high culture encountered low, but contact zones where the firm lines separating the quotidian, bourgeois realities of daily life from the the realm of dreams and unconscious desires terrifyingly blurred and disappeared.”

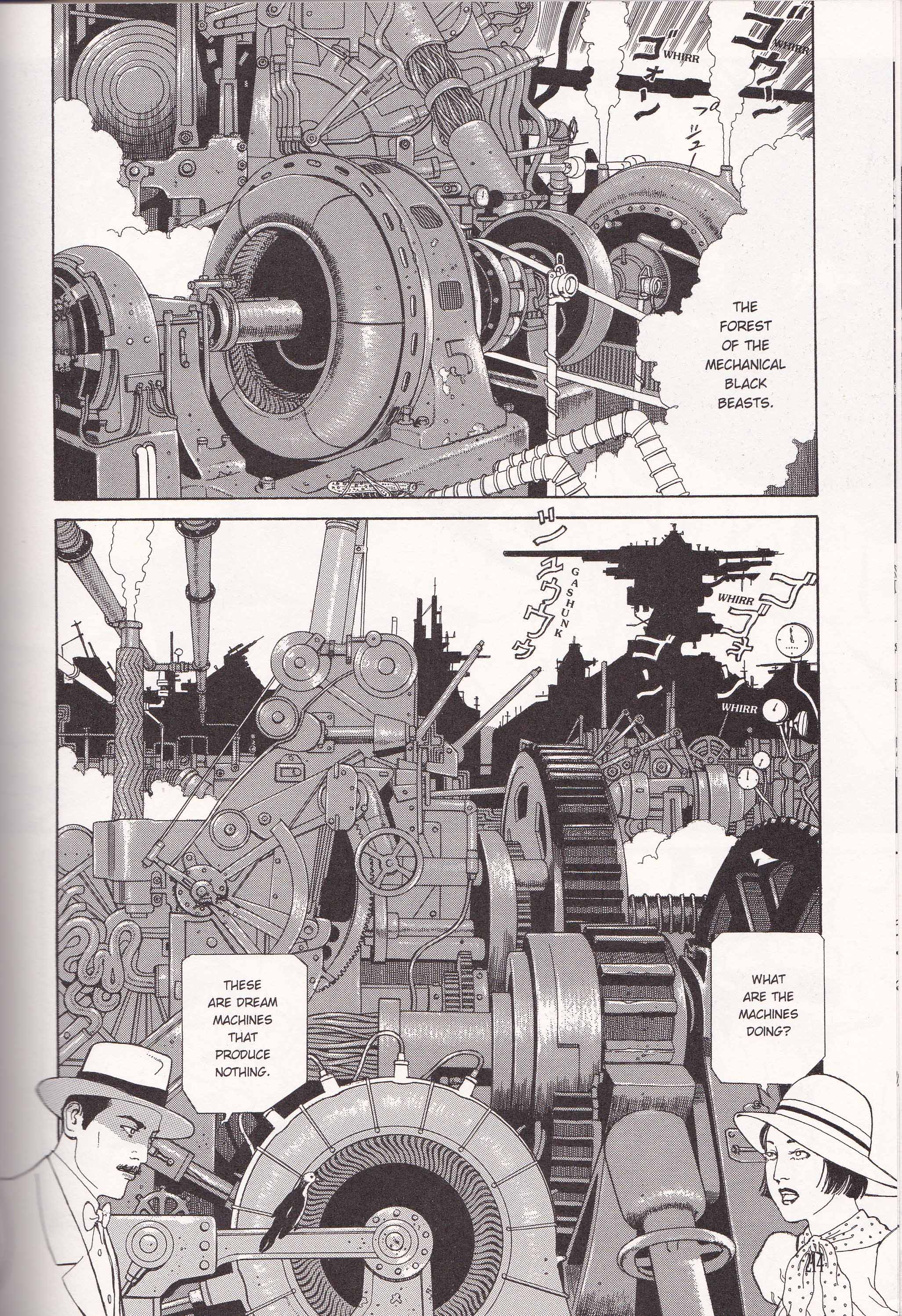

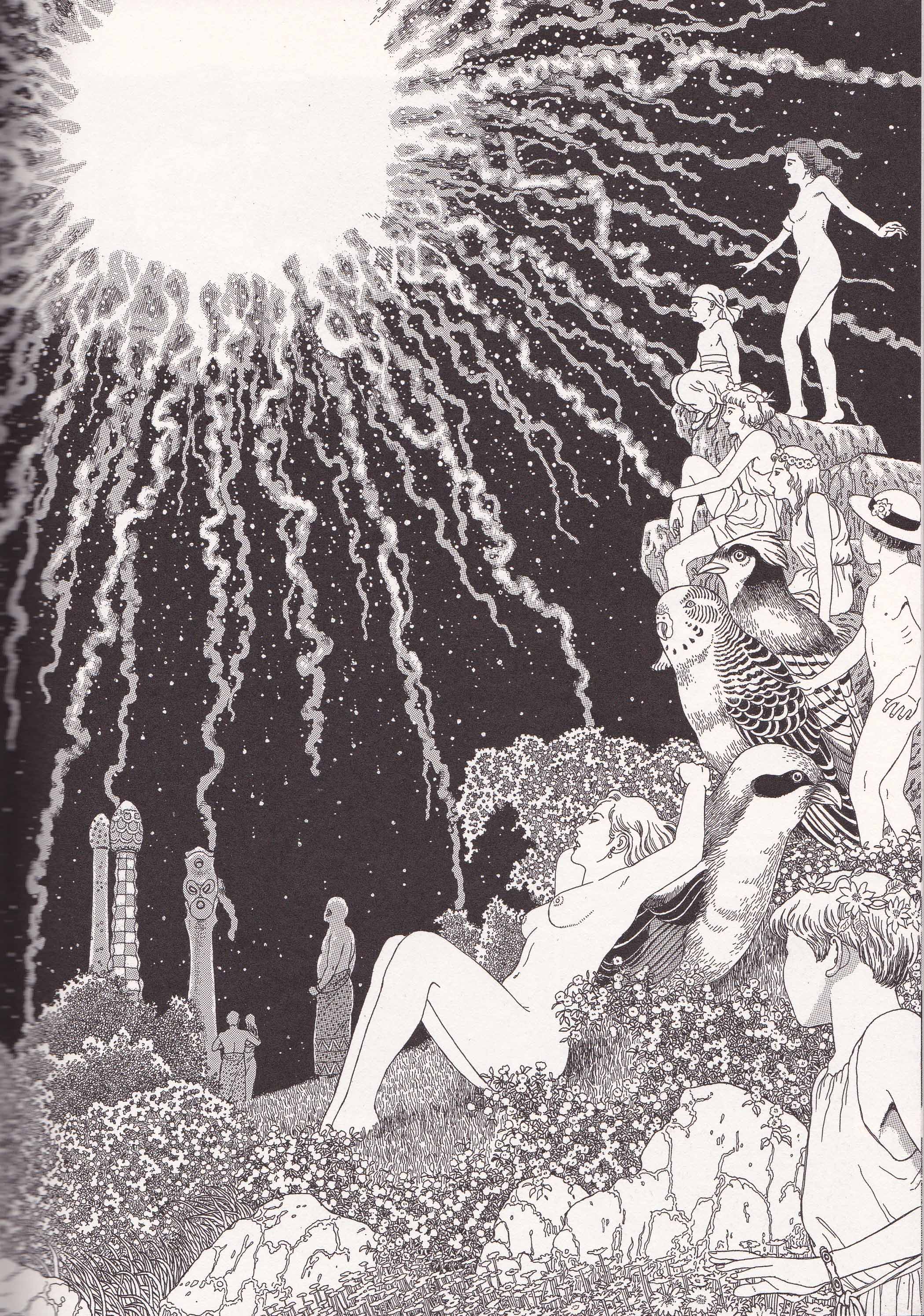

Maruo transcribes both the mechanistic fantasies—the “dream machines that produce nothing”—and the Manchurian wonderland ripe for harvesting in the climax of the manga. It is in such scenes that the comic excels, making tangible the half imagined; not only placing Hirosuke in the banal depravity of a prostitute’s den and the rigid conformity and poverty of early 20th century Japan but opening our eyes to the unbridled fantasies of capitalistic excess.

If the protagonist (in the novel) had once declared an admiration for William Morris’ socialist utopia, then these feelings have been utterly suppressed by rampant greed and an egoistic gluttony. The novella is littered with instances of Hirosuke’s hypocrisy, on the one hand suggesting a preference for Morris’ socialist News from Nowhere and then dismissing the young peasants who discover him in his feigned helplessness (i.e. as a recently “resurrected” Komoda) as a bunch of foolish simpletons:

“He became aware that he was being stared at like some unusual sideshow attraction by sniveling, runny-nosed children with peasant faces, and as he visualized the comical scene, he grew all the more anxious and angry…He couldn’t help despairing. He couldn’t very well get up and scold them…The whole thing seemed so stupid that he felt like dropping everything and getting up in front of the children and exploding in laughter.”

A situation played for humor and irony since he very nearly comes from the same stock and is inserting himself into the highest level of Japanese society

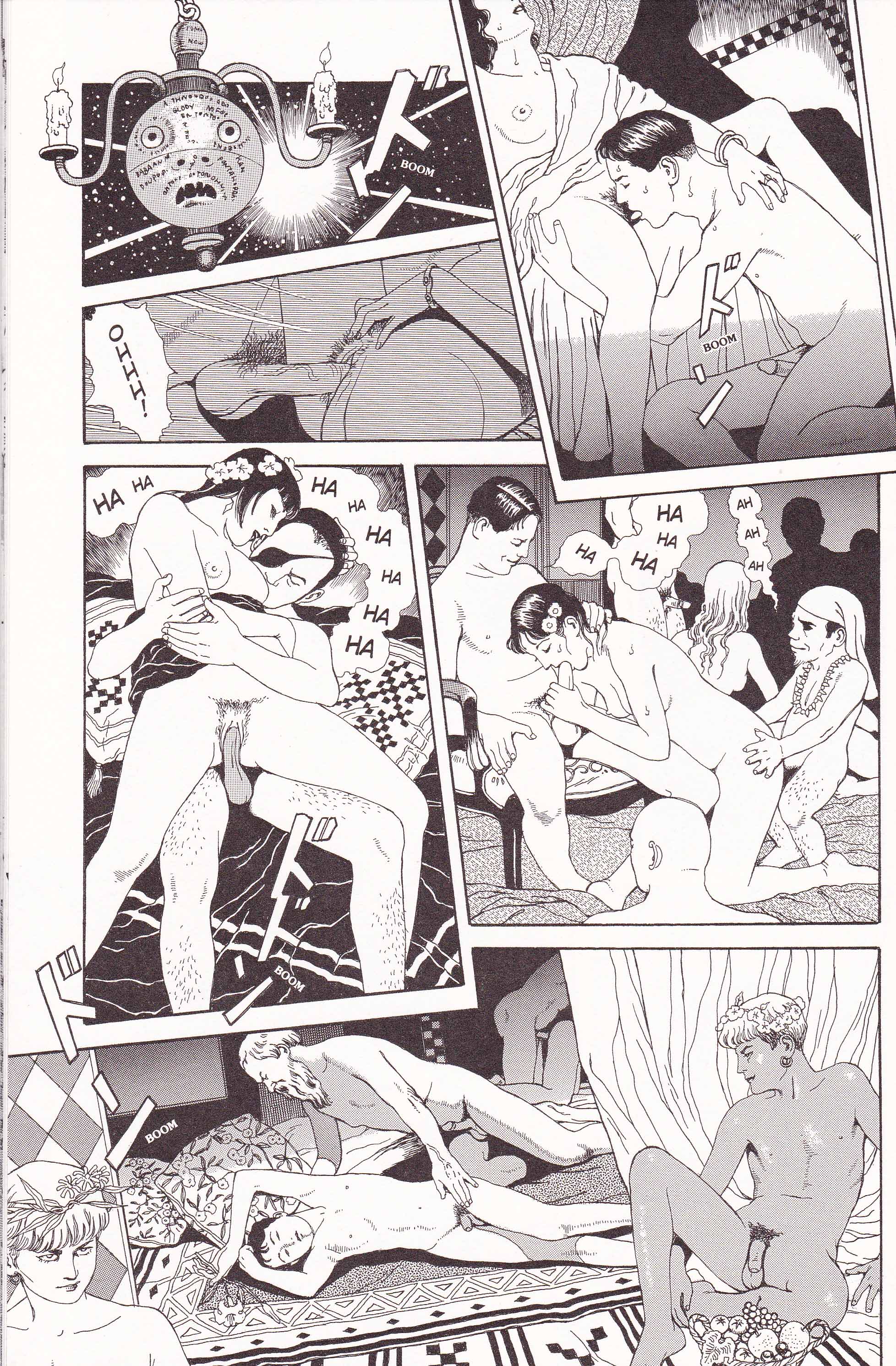

One would expect the sybaritism and licentiousness of Ranpo’s tale to be of primary interest to Maruo and this is very much the case. While Maruo excises Ranpo’s improbable image of the happy couple straddling naked servants in the guise of swans, their thighs chaffing against naked flesh as they navigate a man-made river (perhaps this was considered too fantastic), he is altogether more relentless in depicting Hirosuke’s panorama of nudity and libido.

In the manga, sex becomes an indelible counterpart to artistic intent from the outset, in fact it becomes a presentiment of death (note the Death’s-head Hawkmoth beside the prostitute in the image below). Hirosuke’s dalliances with prostitutes precede an encounter with Genzaburo’s wife whom he fixates on. He seems almost struck with lust at the sight of her and almost immediately put his plan of deception into action. This scene doesn’t occur anywhere in the novella. Where Ranpo posits artistic desire and greed as the primary motives, Maruo suggest base sexual appetite as an equal accomplice.

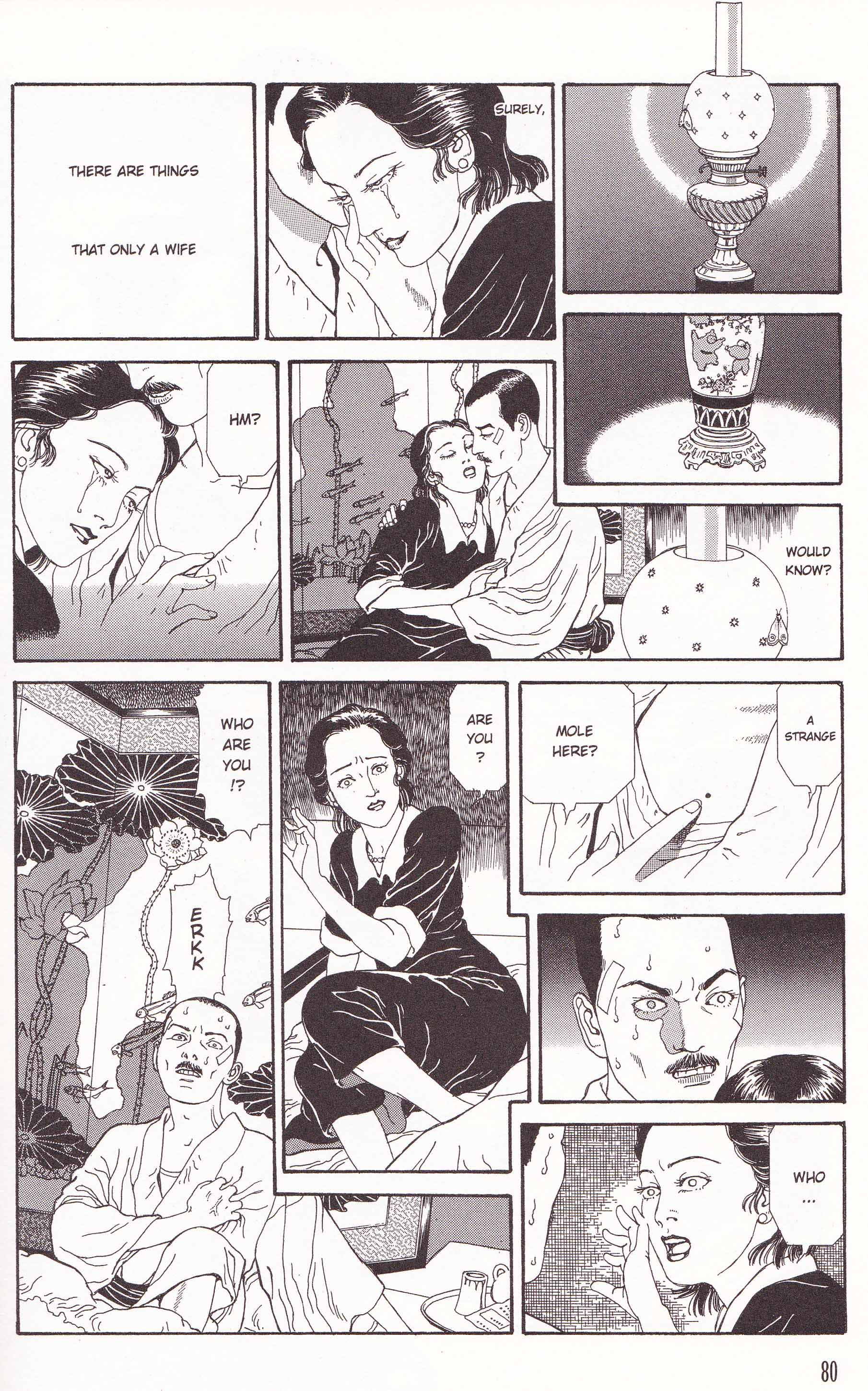

What lies under the surface of Ranpo’s novella is given physical form in the manga. The protagonist of Maruo’s adaptation is vigorous and voracious in his relations with his wife, hardly fearing discovery (and that is exactly what happens in their first encounter): Ranpo’s Hirosuke, in contrast, is characterized by a calculated celibacy, an enforced impotence—a manifestation of his artistic obsession. He abstains absolutely from his wife, ostensibly to avoid detection during intimate contact but inadvertently reveals himself in some unknown way during a drunken stupor. Some bodily deformity or defect of a more sexual nature finally reveals him as an impostor to Chiyoko. The passage in question is left intentionally ambiguous by the author:

Ranpo’s Hirosuke, in contrast, is characterized by a calculated celibacy, an enforced impotence—a manifestation of his artistic obsession. He abstains absolutely from his wife, ostensibly to avoid detection during intimate contact but inadvertently reveals himself in some unknown way during a drunken stupor. Some bodily deformity or defect of a more sexual nature finally reveals him as an impostor to Chiyoko. The passage in question is left intentionally ambiguous by the author:

“Just seeing her eyes, he understood everything. A distinctive part of his body had been different from the dead Genzaburo’s, and Chiyoko had discovered it the night before.”

Whether this is as simple as Maruo’s mole (see image above) or something of a more sexual nature is anyone’s guess. When Hirosuke finally strangles his wife under an orgasm of thunderous fireworks, it seems almost like a case of erotic asphyxiation. He buries her in an unfinished black pillar (in the novella)—a rather heavy handed symbol of his sexual inadequacy—pouring wet cement over her corpse but leaving tell-tale strands of her hair sticking out of the final stiffened mix. This inescapable, almost fatalistic, sloppiness is the final evidence needed for his exposure as a fake and a murderer.

If Poe’s (of whom Ranpo was a great admirer) taphephobia is counterintuitively a longing for the womb, then Hirosuke’s escape from the tomb is the obverse of this situation—a desire for release from sexual repression and the attainment of romantic gratification. Chiyoko is the stye in his eye which once removed results in unbridled carnality.

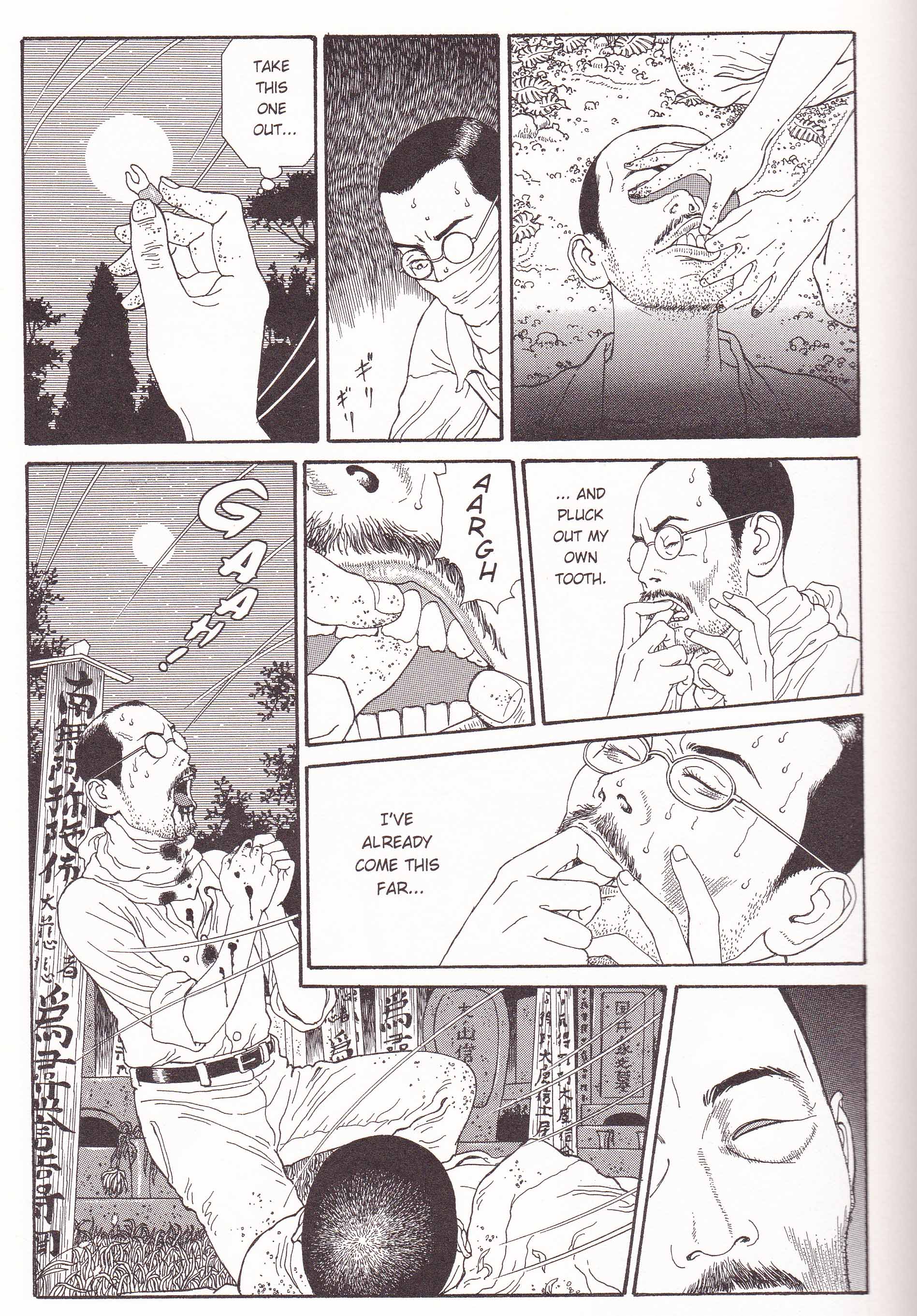

Comics as a form has a way of making obvious the carefully hidden aspects of pure prose but Maruo exacerbates this aspect by insistently giving play to Hirosuke’s licentious feelings and actions. One should also consider the demands on visual imagery in modern day horror fantasies; more precisely, an upping of the ante with each passing year. The prose work is characterized by gruesome detail at precise moments, especially where Ranpo dwells in loving detail on the disinterment of the deceased Komoda which the protagonist plans to impersonate:

“Strangely, he realized that Komoda’s mouth was stretched to a size of ten times larger than it had been while he was still alive. It was open to the point where the back teeth were completely exposed as in the mask of an open-mouthed female demon…[ ]…Although he tried, again and again, to lift Komoda’s decomposing body, it slipped off his fingers each time…When he finished the job, the fine skin of the dead body clung tightly to the palms of his hands, like gloves made of jellyfish, and wouldn’t come off no matter how vigorously he shook his hands.”

Here Hirosuke’s encasement in the decaying skin becomes a metaphor for his own duplicity which soon takes on the decomposition of a rotting carcass. Yet Maruo eschews this, instead presenting readers with an even more violent and improbable episode where he extracts his own incisor with his fingers to mimic the dead Komoda.

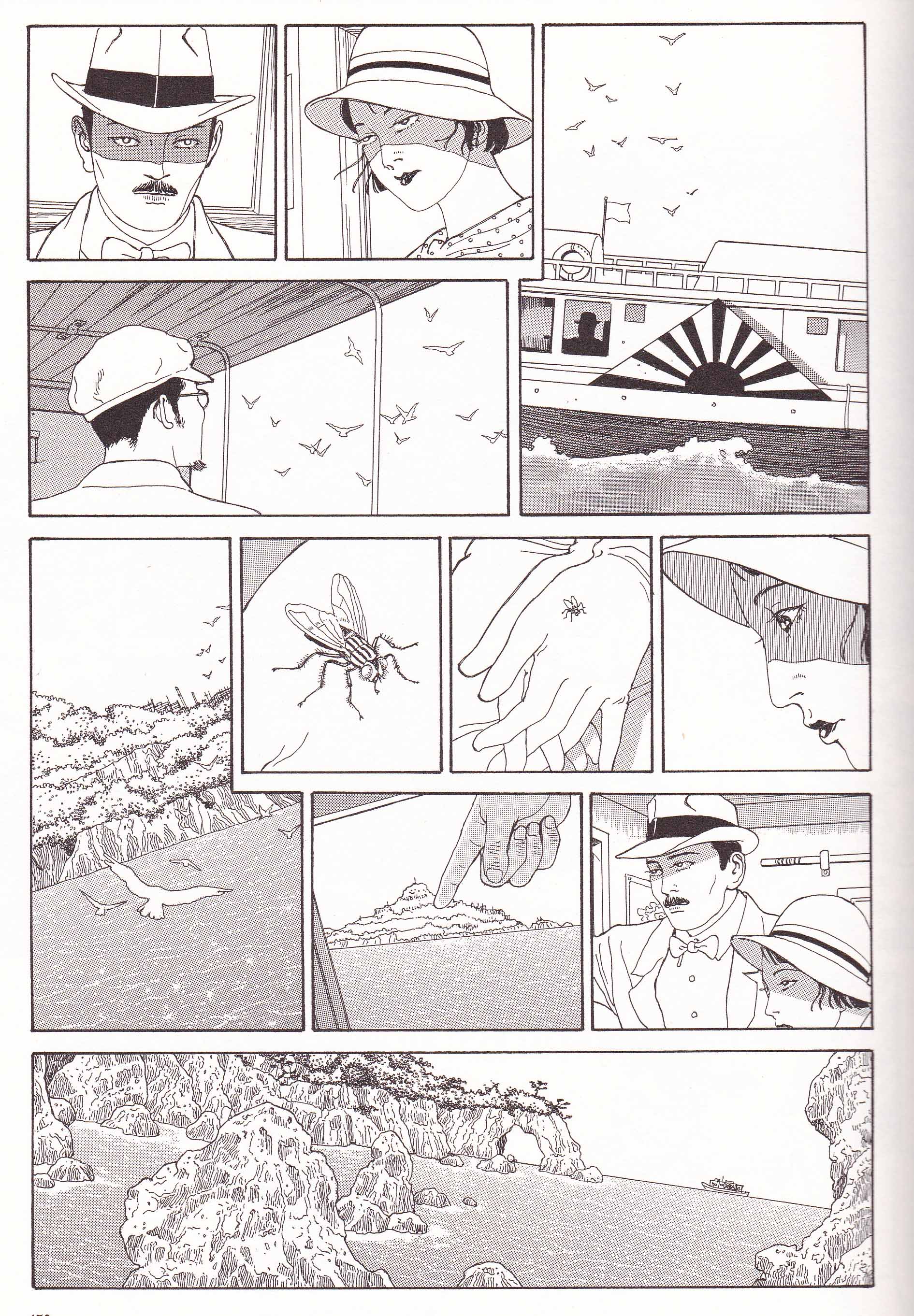

This is not to say that the manga is without moments of insight, subtlety, and interpretation. The glorious spectacles which Maruo reimagines and illustrates towards the close of his comic represent a high point in his cultivated debauchery. At a deeper and more sophisticated level, as the couple travel to the island, Maruo presents his readers with a scene which does not appear in the novella:

A Japanese battle flag is painted on the side of the steamer, and a fly occupies the center of the page. The latter is a note of corruption and a presentiment of the heroine’s death. It is also silent commentary on the direction the Japanese nation soon will take in its search for power, resources, and hegemony. In this Maruo adds an additional layer of meaning to Ranpo’s text, one gleaned from the passage of several decades since the book’s publication; decades filled with horrors perpetrated and suffered by the Japanese state. He forces a comparison between the pure and beautiful Chiyoko (that essential soul of the Japanese people) and her final fate at the hands of a madman.

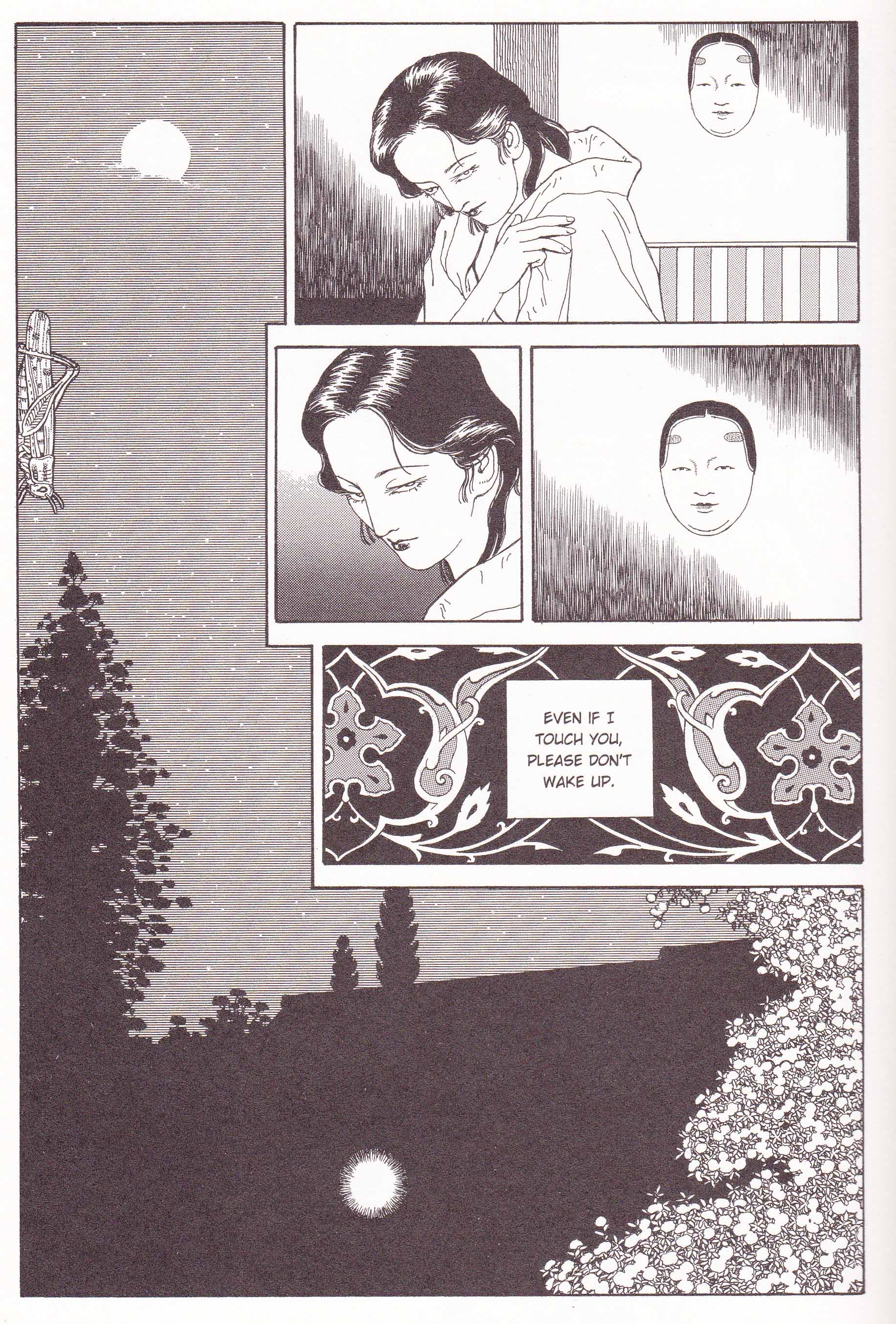

Where Ranpo spends several paragraphs describing the push and pull of Hirosuke’s obsession with Chiyoko, Maruo allows the persistent image of a Noh mask (depicting a young woman) to haunt him throughout the palatial surroundings of his new home—both a proxy for the visage of Chiyoko and an echo of the body he has disinterred

This is encapsulated in an exquisite page where Chiyoko first looks weary and frustrated, and then, with barely bridled longing, out at the reader (just like the subtle head positioning of a Noh actor; see above). A silent cicada crawls down the edge of the frame—both a sign of resurrection and of impending sexual ecstasy.

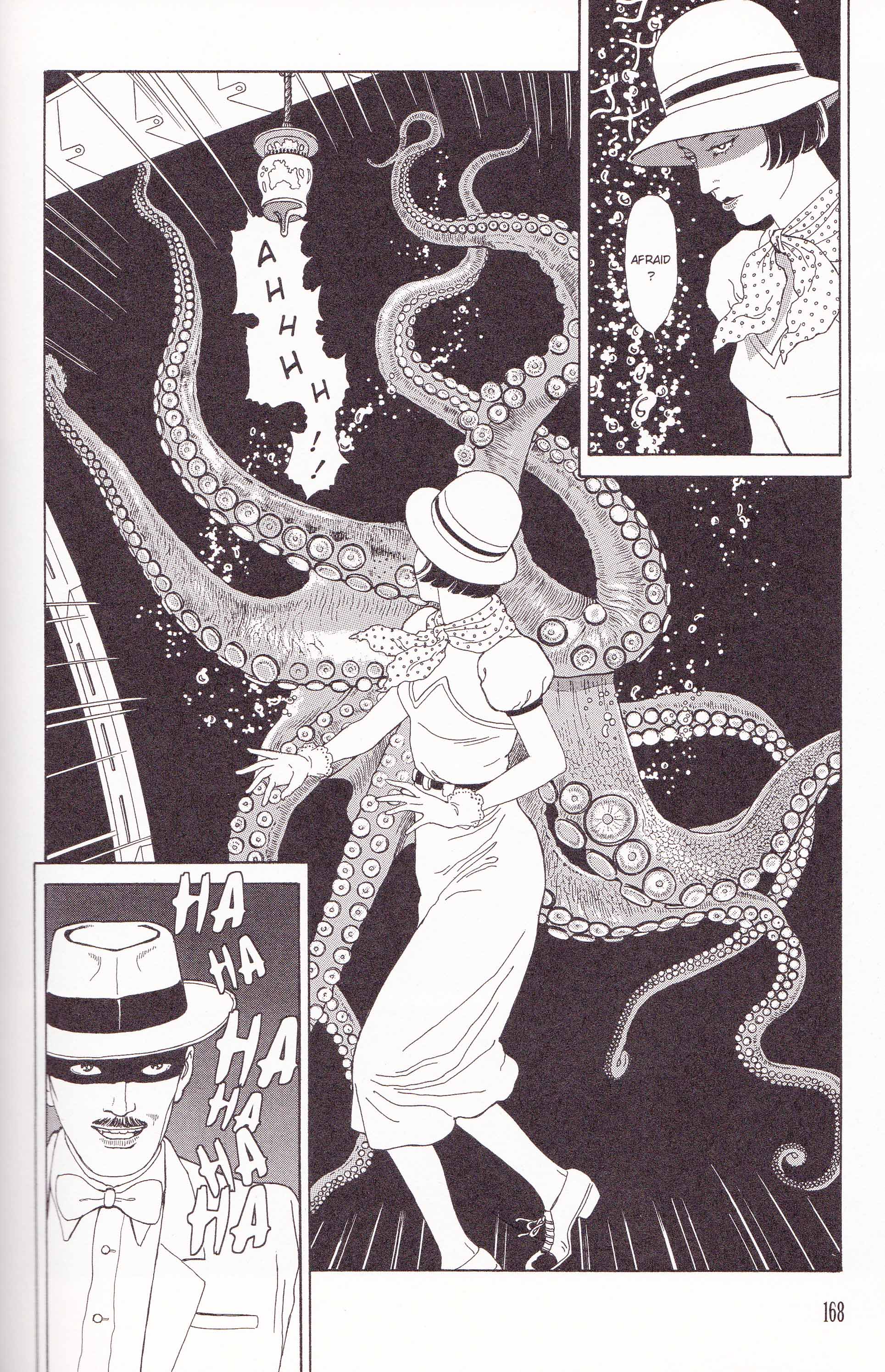

Throughout her tour of Panorama Island, Chiyoko is at once attracted, repulsed, and seduced by all that she sees. She is of no stable state of mind. A critical point in the book is reached when Chiyoko sees a monster “plowing its way through the bubbles” towards her position in an undersea tunnel.

“She felt as if she were being pulled by a magnet. She didn’t have the strength to move away…it looked as if the monster was all head. Its mouth opened just above its short legs, and its small eyes resembling those of an elephant adjoined the protuberances on its back. Its rough and uneven skin was covered with a multitude of bumps topped by ugly black spots.”

It turns out to be nothing more than a “frogfish” magnified through the glass of the tunnel. The monster is the outward expression of Hirosuke’s soul, kept hidden for fear of discovery by his friends and relatives—a natural manifestation of the protagonist’s perfidious character. Chiyoko’s immediate revulsion and then attraction to the sight of this twisted shape is the irresistible yet fatal call of the abyss of technological accomplishment.

This section of the novella is altered in Maruo’s adaptation—no longer stressing the personal excrescence of the protagonist but giving us a tentacled monster with Chiyoko at its heart, perhaps even covering its vaginal maw.

Where Ranpo’s work alludes to a personal and artistic failing, Maruo highlights the contamination brought forth by modernity.

All this suggests that the correct approach to The Strange Tale of Panorama Island would be to first read the manga and then the novel which in many ways is more lurid and certainly more cerebral. In this it reminds me of Fritz Lang’s The Ministry of Fear which while enjoyable in itself suffers from a lack of logical progression and, ultimately, depth of meaning when compared to the Graham Greene novel of which it is an adaptation. The forms and settings of Panorama Island take shape with Maruo’s pictorial representations, sometimes sticking in the mind with their magnificent flourishes, at other times losing in translation that prescient, alluring, and terrible picture of a nation falling into the inferno.

Further Reading

A review by Sam Costello at Full Stop.

“Maruo’s artistry also allows him to provocatively expand on the original novel’s themes of developing modernity. For instance, Chiyoko’s distress stems from a distinctly modern problem: the sense of being too observed. Eyes are a visual motif throughout the book…As Hirosuke and Chiyoko enter the island via a clear undersea tube, Maruo arranges tiny fish to appear like sets of eyes lurking in the dark water. Later, the giant feathers of a peacock are dotted with eyes. The island is thick with statues, all of which seem to leer at Chiyoko. In our YouTube age, being seen isn’t shocking — judging by reality TV and social media, not being seen is more terrifying — but when motion pictures were just 30 years old and photography barely more than 50, it’s easy to understand feeling queasy and disturbed at the revelation of this panopticon. Chiyoko seems particularly unsettled because she isn’t the viewer; instead, she’s part of the panorama, forced into playing a dehumanized role similar to a statue.

Maruo’s work also derives strength from its visual nature when illustrating the tension between modernity and tradition that the panorama — both the exhibit and the island of the story — embodies. For instance, in more than one scene, 30-something Hirosuke wears a modern suit while negotiating business deals with kimono-clad, middle-aged men. This costuming choice more effectively conveys, in just a few panels, the liminal state of the 1920s Japan in which the story occurs than pages of description would.”