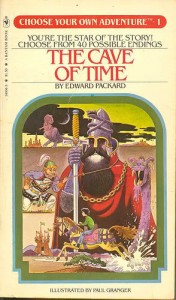

Conception/ Sugarcane Island/The Cave of Time

“What is time?” you ask.

The oracle is silent for a moment, but then answers in a firm voice, “Time is what keeps everything from happening at once.”

“When did time start?” you ask. “And when will it end?”

“Would you like to see?”

You gulp in amazement. “Sure.”

“What then- the beginning, or the end?”

– Edward Packard, Return to the Cave of Time, 1985

He’s told the story many times over the past forty years, and so the words come quickly and easily, spilling out over the gulf between the two of us. In this story it is 1969 and he is the father, and the children are his children, eager for a gripping bedtime narrative. And all Edward Packard has is Pete, washed ashore on a deserted island. And so the father asks the children, “What do you think Pete should do?”

With the power of hindsight we can find some precedents to the Choose Your Own Adventure, forked-path fiction format. But when the concept first hit Edward Packard, it was like a bolt of lightning.

It would have a similar effect on his audience.

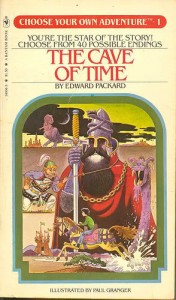

But his ultimate audience was not as immediately accessible as his biological children. Packard wrote the manuscript for his first book in the format, Sugarcane Island, in 1969 and 1970, and had an agent shop it around for years. “They all turned it down- they didn’t see the potential.” So he shelved the book, the whole concept. Several years later Packard saw an article about a start-up publisher named Vermont Crossroads Press, co-owned by one Ray (R.A.) Montgomery. Encouraged by the article, Packard contacted Montgomery and ultimately struck a deal with him, and in 1976 Sugarcane Island finally saw print, as the first in what was intended as a series of books entitled “The Adventures of You.” Montgomery followed up Packard’s book with a manuscript of his own, “Journey Under the Sea.”

-

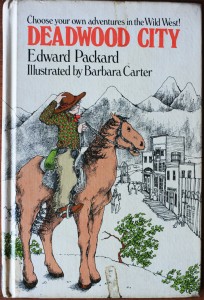

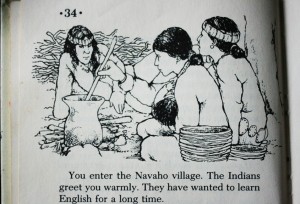

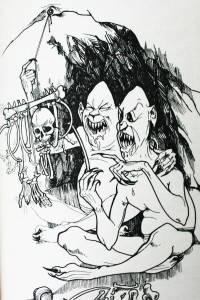

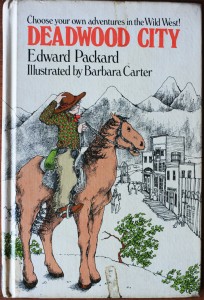

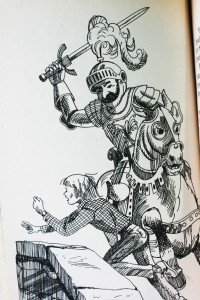

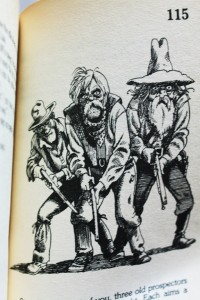

Barbara Carter illustration from the Lippincott edition of “Deadwood City”

Packard, frustrated with the lack of marketing muscle behind the releases, shopped around his concept and some new manuscripts and was eventually able to secure himself a deal with the J.B. Lippincott company. But unbeknownst to Packard, Montgomery and his newly acquired agent were working on a deal of their own with a much bigger company- Bantam Books. “Bantam decided that half of the books would be written or subcontracted through me and half of the books through Ray Montgomery,” Packard told me in a phone interview, almost thirty years after the deal finally went down. “Ray and his agent were really the ones who set it up. I was brought in because I’d started the whole thing.”

Youth/You are a Shark/Secret of the Ninja

There are no stars or suns or moons or wisps of light; not a breath of air; no sound; no smell or taste; no up or down or sideways; no motion; no feeling; nothing but silence. Suddenly there’s a point of light so brilliant, it feels like pins driven into your eyeballs! Even before you can blink, the light expands into a million lightning bolts radiating in all directions. Your eyes shut, but the light is still painfully bright. As you move your hands to cover your eyes you scream- but no sound comes.

– Edward Packard, Return to the Cave of Time, 1985

In the summer of 1988 my family moved across Orlando to a new home in a new neighborhood. When I entered third grade a few months later, it was with more than a little anxiety- I didn’t have any friends, didn’t know the school or the neighborhood at all. But I soon found compatriots, including a sandy-haired boy named Chris M., who would end up being my best friend for the rest of elementary school. And Chris had an inheritance.

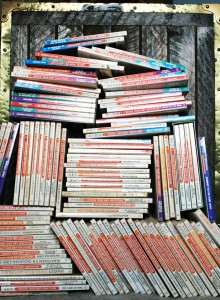

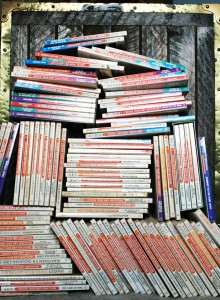

The books were a gift to him from his older sister’s boyfriend- a box full of Choose Your Own Adventures from a few years earlier. We poured over them, relishing the illustrations, the variety of settings and the sometimes lurid titles and subject matter. But what we loved most was the central, binding concept- the branching paths. The feeling it gave of inhabiting someone else’s skin, of living a new situation and being able to explore it in relative safety.

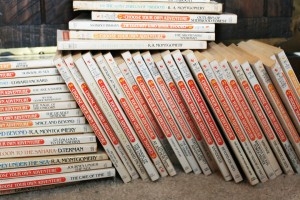

It was a kind of mania for us. The books were still coming out, and we bought as many as we could get our hands on. When we’d have sleepovers we’d pool our books together into one big collection, in chronological order of course, and talk about the missing books, what they might be like, and brag about how big our joint collection would eventually be when we were roommates in college together. Eventually we found that the earlier books were readily available on the cheap at garage sales and second hand stores of all types, and so our collections continued to grow.

All this emphasis on collection might imply that we didn’t read them- we did- we even had strong opinions about the book’s authors. (Edward Packard’s books, we deemed, were the most “fair”, and internally consistent, and often the most fun as well. Although we often were drawn to the concepts and themes of R.A. Montgomery books, we were put off by the lack of narrative logic and internal consistency, and what we saw as didactic, judgmental and sometimes capricious results from each choice.)

So I loved the reading. But the aspects of collectability were what fueled the mania. Firstly, they were numbered, which meant that after having acquired a handful gaps started to appear. Secondly, the books by various authors were often indirectly related to each other, or sometimes even direct sequels. The small connections from book to book served to heighten my interest in obtaining the other books.

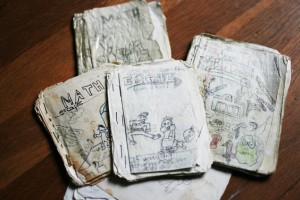

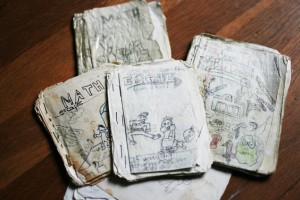

Chris and I were obsessed enough with the format that we produced several Choose Your Own Adventure-format books of our own over the next two school years, including such classics as Escape From School, Math Escapes, More Escape From School, Gut Squisher, Save the Big Dudes, and a revised version of Math Escapes, with added violent behavior.

- Escape from School, by Chris M and Sean Michael Robinson, age 8

Rereading the particular books that obsessed us as children, it’s not hard to see what fascinated us. For more than a decade Edward Packard was one of the most innovative writers working in children’s fiction. He found the perfect formula in his first book, and so he could spend the next several years breaking, manipulating and stretching it.

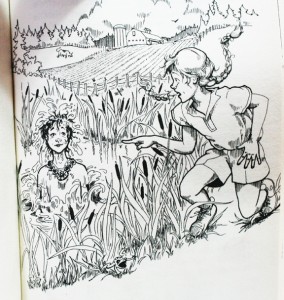

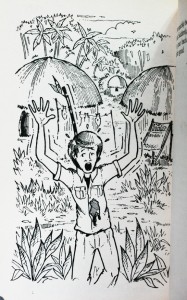

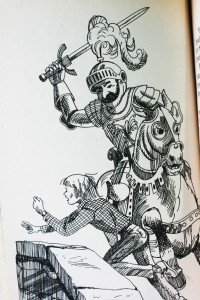

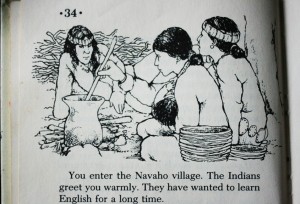

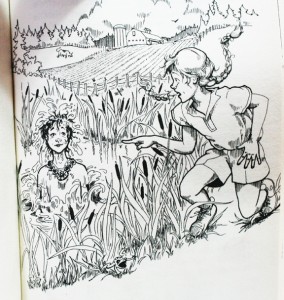

For Packard the formula wasn’t just the concept of branching path fiction– it was also the emphasis on you, the reader, the traditionally robust role of protagonist making way for the ego of the audience to fill in the gaps. This intention was often undercut by the Bantam illustration concept, which more often than not represented the protagonist as a ten-to-fifteen-year-old white boy. In rare instances this tendency was reversed , such as many of the female-protagonist (or even gender-unidentifiable) fantasy-themed books (Outlaws of Sherwood Forest, Mystery of the Secret Room, and the Enchanted Kingdom, all written by Ellen Kushner and beautifully illustrated by Judith Mitchell).

-

-

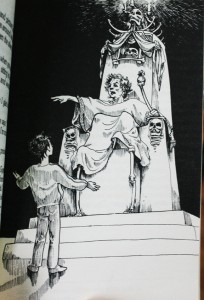

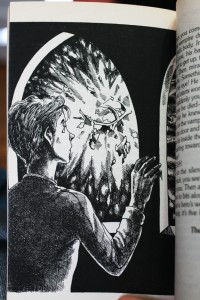

“Mystery of the Secret Room” written by Ellen Kushner and illustrated by Judith Mitchell

I disagree with Packard as to the importance of the empty vessel– I don’t really believe such a thing is possible, even without illustrations. If the author is doing her job creating an environment and situation for you to explore, a natural result will be a character, even if it’s a character created solely by inference. Additionally, even as a younger reader I was very aware of which “characters” I liked and identified with, and how this changed my interaction with the book. I remember as a young boy finding the stories in which “you” were represented as a female strangely compelling, and finding myself drawn to the images of the female protagonists, studying them, trying to read their intentions and motives.

-

The Enchanted Kingdom, written by Ellen Kirshner and illustrated by Judith Mitchell

In the very early books, Packard himself deviates from this empty vessel prescription, and this makes for some of the more varied books in the series. You can sense him playing with the formula. In “Your Code Name is Jonah” you are a C.I.A agent, in “Who Killed Harlowe Thrombey?” a detective, two jobs not typically held by ten-year-olds. Perhaps a result of the wider variety of protagonist roles, these early books seemed a lot more off-the-rails and experimental than many of the later ones.

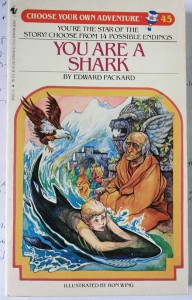

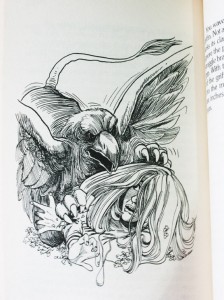

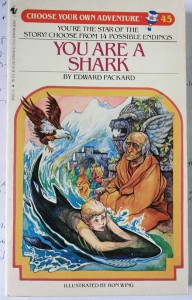

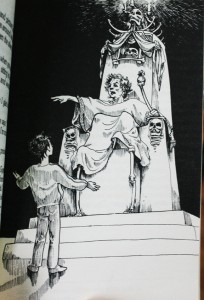

Packard wrote a lot of books, and not all of them are classics. A great deal of them are simply his treatments of standard adventure fare (Deadwood City, Survival at Sea, Sugarcane Island). And then… there are the few books of his that defy categorization. How would you describe “You are a Shark” to someone that’s never read it? It’s at once almost idiotically simple and yet profound and strangely moving- you visit the ruins of a temple in Nepal and enter, despite knowing you shouldn’t. And you find an impossibly old man inside the temple, who stares straight ahead, gazing into space, as you feel a flash of panic, and slide helplessly to the floor.

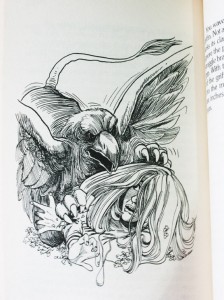

-

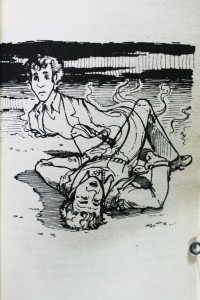

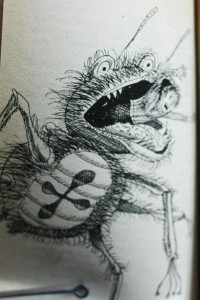

“You are a Shark” by Edward Packard, illustrated by Ron Wing

Though your body is alive your spirit has moved on to the body of another being. You move over and over again against your will, from animal to animal, while your body slowly perishes. For my third grade self, this was deeply moving stuff.

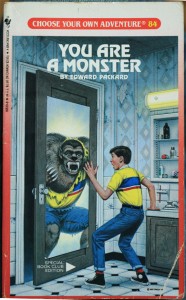

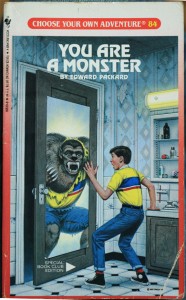

Adolescence/You are a Monster/ You are a Superstar

Pain. That’s the worst part of it. You can hear your bones cracking as you grow. Your muscles are growing too. They ache as they stretch to keep up with your bones- especially your arm bones, which are lengthening and thickening the most. Your skin is expanding, trying to cover your widening body surface. Sometimes it’s stretched so thin, you’re afraid it’ll split, but it always seems to cover.

– Edward Packard, You are a Monster, 1988

In those fevered two years of Choose Your Own Adventure obsession, I had no way of knowing that the best creative years for the series were already past. With more than eighty books already out, the past itself seemed infinitely rich, and so if I saw the signs I didn’t understand them. Eight years in the series had settled into a comfortable formula- easily explicable concept, punchy title, early dump of the author’s research in the setup to the story, and a decreasing amount and variety of choices and endings. Packard told me, at least in his case, that this was largely “a trade-off,” but it “wasn’t deliberate. I tended to want to expand the plot more, to try to make it richer, and the more a particular storyline gets involved, the less you want to branch it off.” Page count staying the same, the functional result of this was fewer choices, fewer random deaths, and less of the metaphysical wackiness that defined the books in opposition to other adventure books of the time.

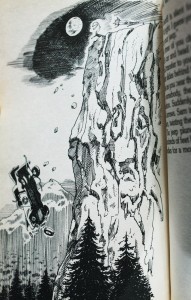

From an aesthetic standpoint, the books also finally made the transition to the eighties, with bright gradient backgrounds and hideous photo-realistic paintings on each cover. Although many of the excellent pen and ink interior illustrators managed to hang on for a while longer, they were gradually replaced by heavily-photo-referenced, toned pencil illustrations that completed the aesthetic transformation.

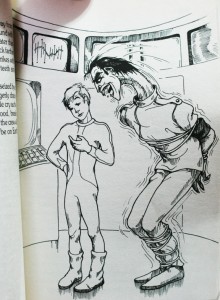

-

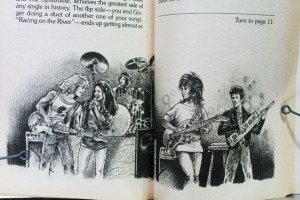

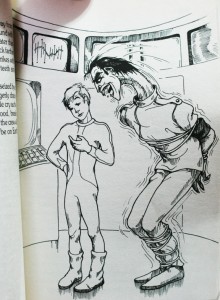

a heavily referenced illustration by Stephen Marchesi for the book “You are a Superstar”

As for my interest in the books, and my friendship with Chris, both were long gone. Choose Your Own Adventure survived them both, in publication, if not in spirit.

Even as I moved through middle school I still found places to get my fix of interactive fiction. In sixth gradel I finally acquired a Nintendo, followed a year or two later by an SNES, and I discovered in short order a whole new realm of interactive fiction, namely the Japanese console-based role playing game. I would have become disinterested in the books eventually anyway, as they were aimed at fourth to sixth graders- but having a viable substitute certainly helped accelerate the process. Strange rumblings were happening at school too, every time we visited the computer lab. The school had replaced their Apple IIGS lab with an entire room of Macs, all of which came preloaded with a piece of software called Hypercard that felt strangely familiar to many of the students who used it. We were encouraged to build our own stories- draw a picture, have some text, and have some picture or text element that could be clicked through to advance the story. And from there the cards could branch out into many different directions.

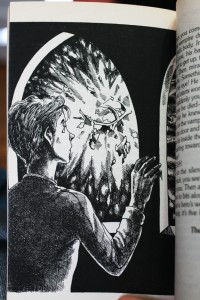

-

From “The Manhole,” a Hypercard adventure game from 1989

- from “Electronic Whole Earth Catalog,” an educational Hypercard stack from 1989

I didn’t need to make the direct connection myself- our teacher pointed it out to us the first day we used it. “We’re going to make stories, like Choose Your Own Adventures. You guys can draw and write your own stories, and we’ll make logic trees, little maps, to keep track of the whole thing and make sure you don’t leave any loose ends.” (although Hypercard itself has been long forgotten, many more people seem to remember Myst, once the biggest-selling PC game of all time. Myst was a series of Hypercard stacks.)

- The most successful Hypercard stack of all. Myst, Robyn and Rand Miller, 1993

It took me several months of computer lab time, but by the end of sixth grade, my one and only Hypercard creation, “Revenge of Abraham Lincoln” was complete.

Another year later and I had my first experience with the Internet. Another year after that and the web was on the horizon. Edward Packard, Apple and a vengeful clone of Abraham Lincoln had successfully prepared me to embrace the hypertext environment.

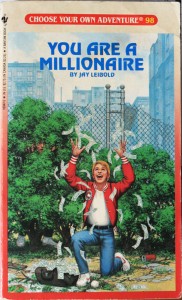

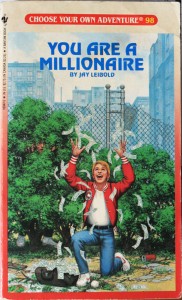

Adulthood/”The Worst Day of Your Life”/”You Are a Millionaire”

You are a decider,” she says. “Because you are from a primitive culture you do not understand that constant pleasure is superior to freedom of choice- though that should be obvious to anyone.”

– Edward Packard, Return to the Cave of Time, 1986

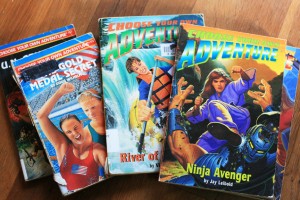

In 1998 Chris and I both graduated high school, the same year that Bantam ceased ordering new books from Packard and Montgomery, effectively ending the CYOA series. Was it part of the natural cycle of the market, or had the need for interactive fiction been satisfied by increasingly complex story-based console role playing games? Or had CYOA been done in by some factor much more mundane, like the continual paper price hikes of the mid to late nineties? I never saw the books at the time, but I’ve read some of the nineties books recently, and there is a feeling of desperation in the air- too many concepts that seem to be chasing trends or rehashing past successes, and a drastic (and aesthetically disastrous) mid-series visual makeover.

Before our graduation Chris and I had a brief reunion, worked on a comic together in our Physics class, and even kicked around the idea of writing some more interactive fiction. Sadly for us, we never got farther than a list of rather promising titles, before we were waylaid by life, girls, and more bitterness towards each other. (for the curious, the prospective titles were- “You are Homeless,” “More Math Escapes” and “You are a Teenage Girl.”)

-

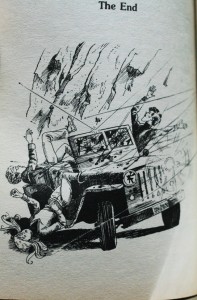

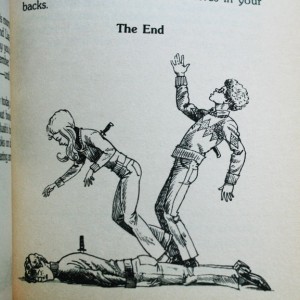

Photoshop, format changes and robotic martial artists- it was the end of the road for CYOA

Edward Packard and his former business partner R.A. Montgomery had a falling out of their own, one that has indirectly led to the odd state of the Choose Your Own trademark today. Currently the CYOA trademark is owned by Chooseco, which is in turn owned by one R.A. Montgomery, prolific writer of mediocre children’s fiction. The consequence of this is that the brand itself no longer features any work by the originator of the concept the brand is based on- no Edward Packard books will ever again be issued under the CYOA moniker.

And yet- we live in the future, and in the future nothing is dead forever. And so the trademark-less Edward Packard has teamed up with Simon and Schuster to re-imagine some of his CYOA books as iphone apps, under the new mark U-Ventures. And so time marches on.

As for the books themselves, it’s still possible to pick them up at rummage sales, book stores and ebay for pennies on the dollar, and the first sixty or so in the series, in addition to being the best, also happen to be the easiest to find. If you’ve never read a CYOA and would like to do so, or if, like me, you were obsessed as a child and now find yourself curious again, may I be so bold as to recommend a few titles for you?

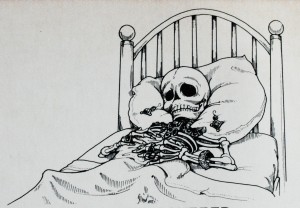

- Cave of Time (1)- Edward Packard- Not an excellent book, but very interesting to see how expansive the concept was from the very beginning. Long before a certain hot tub made time travel much more convenient, you wander through a cave in which every corridor leads to a different era.

- Your Code Name is Jonah (6)- Edward Packard- I seem to have a soft spot for Cold War political thrillers involving secret messages embedded in whale song.

- Hyperspace (21)- Edward Packard- Off-the-wall metaphysical gamesmanship meets buckets of pseudoscience, and what emerges is delightful, eccentric gobbledygook.

- Supercomputer (39)- Edward Packard- Has the distinction of being one of the goofiest books about technology written in the eighties, in an era not exactly known for its skepticism about technology. Fascinating, fun tangents into world politics and theories of wealth and happiness.

- You are a Shark (45)- Edward Packard- Reincarnation and bloodletting in an ancient temple in Napal. See above.

- Outlaws of Sherwood Forest (47)- Ellen Kushner. Guess what it’s about? More beautiful illustrations by Judith Mitchell.

- Return to the Cave of Time (50)- Edward Packard- A mess of adventure, theory and possibility.

- Magic of the Unicorn (51)- Deborah Lerme Goodman- Fun fantasy with nice illustrations by Ron Wing

- Enchanted Kingdom (56)- Ellen Kushner- Fun funny faerie adventures with sometimes brutal endings. Beautiful illustrations by Judith Mitchell.

- Mystery of the Secret Room (63)- Ellen Kushner. Two boxes and a mess of trouble. More beautiful illustrations by Judith Mitchell.

- The Worst Day of Your Life (100)- Edward Packard- An extreme, and extremely raucous, adventure book that also happens to be a meditation on the nature of disaster. A fine return to form for Packard.

The End

The End

The End

The End

The End

The End

The End

The End

The End

The End

The End

The End

The End

The End

The End

The End

The End

“There’s not one perfect path. Usually there’s a whole spectrum of outcomes, of adventures. The idea is to try to mirror life in a way, all the possibilities of life. It isn’t either you get a pot of gold or you die. [There are] all kinds of things in between.”

-Edward Packard, interview, 2010

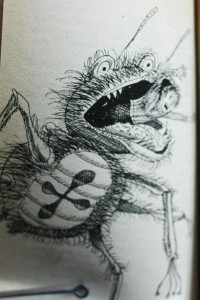

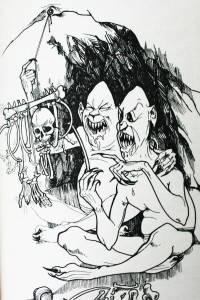

[special thanks to Edward Packard for his kindness and consideration. illustrators at the end, from top to bottom- 1-3 by Paul Granger, a.k.a. Don Hedin; 4 by Ted Enik; 5 by Anthony Kramer; 6 by Judith Mitchell; 7 by Paul Granger, a.k.a. Don Hedin; 8 by Ron Wing; 9-10 by Judith Mitchell; 11-13 by Paul Granger a.k.a. Don Hedin; 14 by Ted Enik; 15 by Paul Granger a.k.a. Don Hedin; and lastly, 16 by Judith Mitchell.]

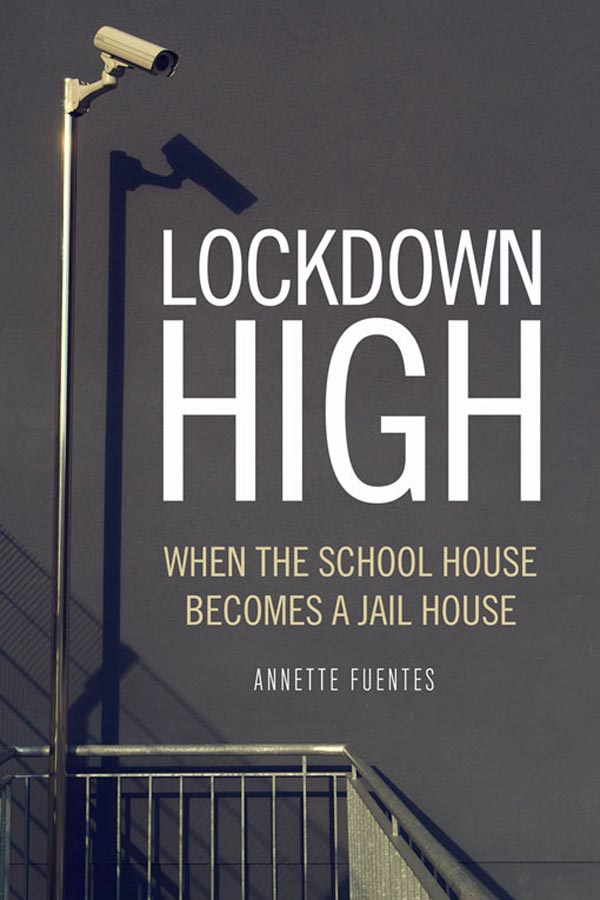

Prisons are not the ideal venues for education. Therefore, it is not a great idea to turn schools into prisons. As a corollary, treating children as if they were hardened criminals does not imbue them with the joy of learning. If you brutalize students and treat them with contempt, they will not buckle down to their work with renewed vigor and enthusiasm. On the contrary, they will start to react to school the same way that prisoners react to prison. Which is to say, they will want to get. out.

Prisons are not the ideal venues for education. Therefore, it is not a great idea to turn schools into prisons. As a corollary, treating children as if they were hardened criminals does not imbue them with the joy of learning. If you brutalize students and treat them with contempt, they will not buckle down to their work with renewed vigor and enthusiasm. On the contrary, they will start to react to school the same way that prisoners react to prison. Which is to say, they will want to get. out.