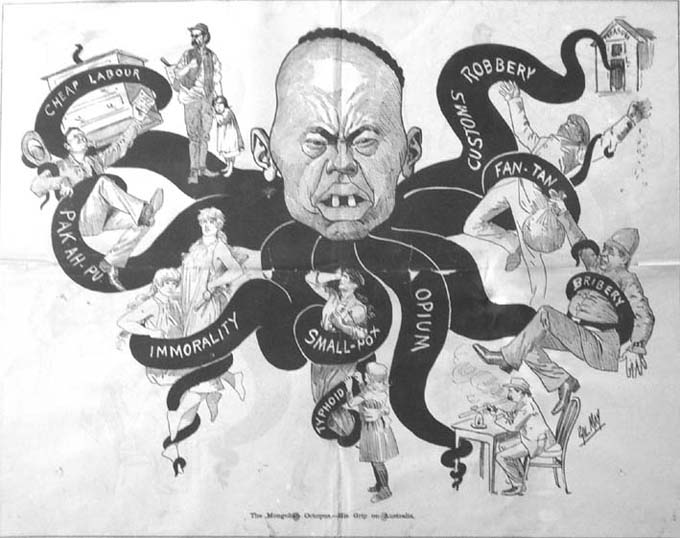

The Yellow Peril is an old frienemy of ours. We officially made its acquaintance for the first time at the end of the nineteenth century, when the catchy comic book villain-esque name was coined as a popular term for underpaid Chinese laborers in the United States, playing on the fear that an influx of Asian immigrants would destroy Western civilization and values. The phrase came back swinging roughly half a century later, during World War II. This time, of course, the Yellow Peril was Japanese. The basic story remained the same, though, painting people of color – specifically those of Asian descent – as an inscrutable and exotic threat to the “true” America, otherwise known as white America. And stories, as we know, have consequences. Fear of the Yellow Peril fueled the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act, which placed some of the heaviest bans on free immigration in U.S. history. That same brand of fear inspired the internment of more than 100,000 Americans in 1942 – for the great and terrible crime of being born with Japanese ancestry.

Phil May, The Mongolian Octopus

Fast forward to the twenty-first century. November 2012 saw the release of action-adventure blockbuster Red Dawn, the thrilling tale of evil North Korean terrorists invading an American town, where they’re fought off by a bunch of white kids. Barely four months later, in March 2013, the theaters treated us to Olympus Has Fallen, the thrilling tale of evil North Korean terrorists invading the White House, where they’re fought off by the white President and his white Secret Service buddy.

Now, this narrative premise – although a bit tired and recycled by now – isn’t inherently a bad one. The Korean War, a distant memory for most Americans, is technically still alive and well on the Korean penninsula. The past year has seen some alarmingly aggressive rhetoric from Pyongyang, culminating in its third nuclear test in February 2013, along with threats of military action against both its South Korean neighbor and the United States. The art of storytelling – whether on paper, stage, or the silver screen – makes an excellent vehicle for examining the nuances and complexities of real life tensions, and the current North Korean government definitely serves up plenty of fodder for discussion.

The trouble is, movies like Red Dawn and Olympus Has Fallen aren’t interested in nuances or complexities. They just want to rehash the tale of the Yellow Peril for a modern audience, and North Korea makes a convenient vehicle. A secretive totalitarian state with nominal Communist sensibilities and nuclear ambitions? It’s practically a Hollywood wet dream. Never mind that even fueled by its pervasively militaristic culture, North Korea’s standing army remains both under-trained and under-equipped. Never mind that the North Korean governments’s infamous human rights abuses – ranging from slave labor to public executions – have been overwhelmingly directed toward actual North Korean people, not foreign enemies. Never mind that North Korea can barely afford to feed itself, and in fact relies heavily on aid from the U.S., South Korea, Japan, and a plethora of other foreign nations, just to stave off starvation. North Korea is far from the friendliest kid on the international block, but the vast majority of victims on the receiving end of North Korea-related atrocities aren’t American, or even South Korean. They’re North Korean.

You wouldn’t know any of that, from watching either of these movies. The North Korean antagonists are monstrously powerful, utterly unrepentent, and have somehow magically gained the resources overnight to go from starving and insular to suddenly, invading Washington, D.C. with top-of-the-line weapons tech. You’d think that – having apparently unearthed the goose that lays the golden egg – their first order of business would be to fix that pesky yet rampant malnourishment problem, but Hollywood logic will be Hollywood logic.

Now, Hollywood has never exactly been a beacon of accuracy. We go to the movies for entertainment, and if entertainment means larger-than-life fight sequences and gun fu, so be it. But there’s a difference between handwaving the laws of physics and promoting white nativism and race-based fearmongering. These are the facts: the main heroes of both Red Dawn and Olympus Has Fallen are white, and the villains are people of color. The heroes are played, respectively, by Chris Hemsworth and Gerard Butler. The villains are played, respectively, by Will Yun Lee and Rick Yune.

Here’s the thing. Chris Hemsworth is Australian. Gerard Butler is Scottish. Meanwhile, Will Yun Lee and Rick Yune? Both born and bred Americans. In a movie that’s all about patrotism and standing up for the United States, we’ve got the hometown heroes played by foreigners and the villainous invaders played by Americans. That in itself might not be so bad – after all, stepping into someone else’s shoes is what actors are paid to do, and Butler and Hemsworth wouldn’t be the first to play outside their nationalities – except that the lines are drawn so very starkly. Asian-Americans don’t exist in the world of these movies. No, Red Dawn and Olympus Has Fallen teach us that real American heroes are white, even when they spend the whole movie awkwardly trying to conceal non-American accents. On the other hand, if you’re Asian, you’re obviously some inscrutable foreign Other, concerned with nothing but tearing down the good old USA. At best, you might be a really sneaky evil Asian guy pretending to be a nice Asian ally – a la Rick Yune the North Korean terrorist posing as a South Korean diplomat – but by the end of the film, you’ll inevitably show your true colors as a scary anti-American evil-doer of supervillainous proportions.

Ironically, the recent release that arguably best deconstructs the problems with the whole “beware the non-Caucasian” narrative is a fellow member of the action-adventure genre – and initially looked like it had all the trappings of yet another Yellow Peril film. Iron Man 3 hit theaters in May 2013, a couple months after Olympus Has Fallen, and featured the villain known as – you guessed it – the Mandarin. Here we go again, we thought. We all saw the previews of half-Indian Ben Kingsley in the samurai topknot and the ambiguously foreign-looking robe, playing the ambiguously brown terrorist. We braced ourselves. What else were we supposed to expect?

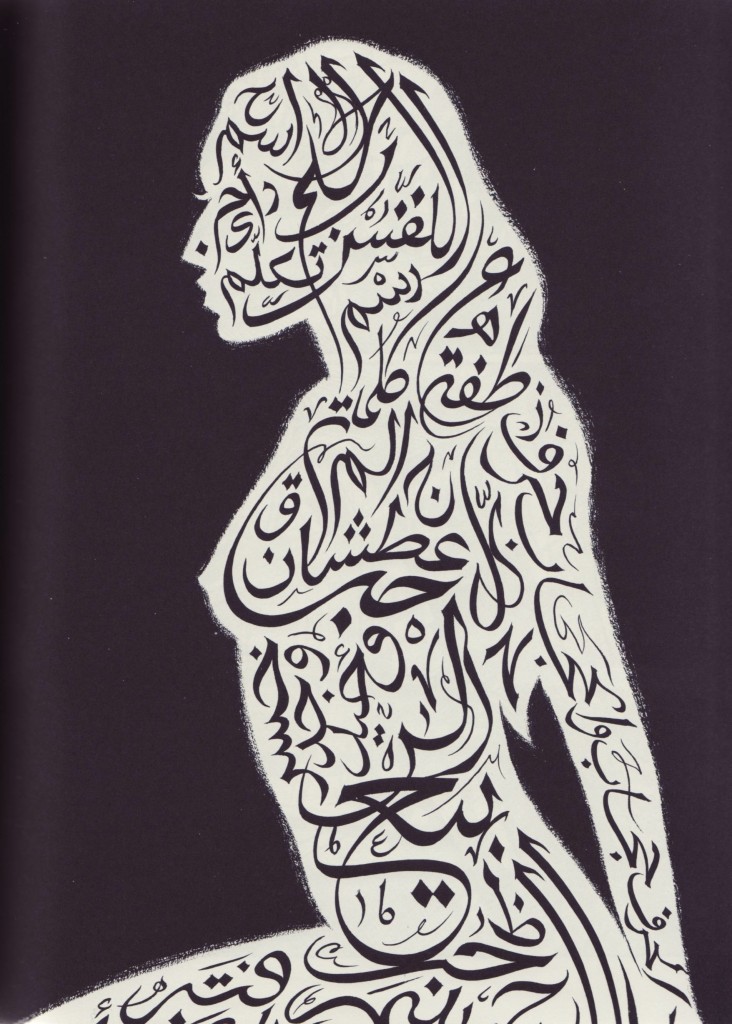

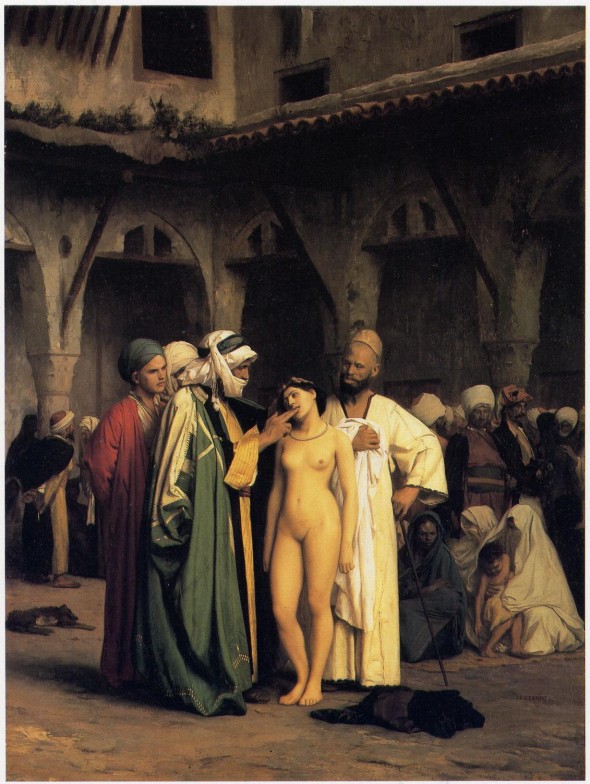

Except, it turns out, the Mandarin is a sham. The Mandarin persona is quite literally the creation of Aldrich Killian, the true antagonist of the piece: a white guy who invents a fictional, scary brown villain – complete with a hodgepodge set of “Oriental” iconography and props – so that Killian himself can profit from the ensuing public panic. It’s a deliciously meta-filled plot twist straight out of Edward Said’s seminal Orientalism, published in 1979, in which the Palestinian-American scholar wrote, “The imaginative examination of all things Oriental was based more or less exclusively upon a sovereign Western consciousness out of whose unchallenged centrality an Oriental world arose.” In short, says Said, the idea of the “Orient” – that unfathomable, exotic Other – is nothing but a fanciful product of Western imagination.

The Mandarin of Iron Man 3 is the Orient personified. Like the cartoonish North Korean villains of Red Dawn and Olympus Has Fallen, he’s an elusive fiction who inspires fear and panic, but to no productive end. Similarly, in the wake of Dawn and Olympus, we saw such gems on Twitter as, “I now hate all Chinese, Japanses, Asian, Korean people. Thanks” and “Just saw Olympus has fallen. I wanna go buy a gun and kill every fucking Asian.” Those tweets are just the tip of the iceberg. There are hundreds – maybe more – comments just like them, all spouting the same antipathy toward anyone who might trace their heritage to the other side of the Pacific. Spelling and grammar issues aside, these reactions point to a disturbing trend of xenophobia, jingoism, and ultimately, ignorance-fueled racism.

That’s not patriotism. That’s hate. We may be more than fifty years past Japanese-American internment, and more than a century past the Chinese Exclusion Act, but we obviously haven’t moved past the myth of the Yellow Peril. Korean-American actor John Cho, of Harold and Kumar and Star Trek fame, has remarked, “It’s very difficult to find an original thinker in terms of casting when you’re talking about race at all. And really, although more egregious versions of Asians have fallen by the wayside and become unfashionable, new Asian stereotypes [continue to] pop up.”

Given the political climate on today’s world stage, a North Korea-centric film isn’t necessarily a bad idea. A thoughtful, well-written, and well-performed North Korea movie – rather than fueling ignorance, which fuels fear – has the potential to enlighten and educate the American public on a real and pertinent topic. Such a film could, moreover, easily contain a place for Asian-American heroes, shelving that damaging, long-overused “white man versus the man of color” trope, in favor of something fresher, bolder, and ultimately, a far more interesting tale to tell.

We need stories that speak to a broader American identity, reminding us that we are a nation of immigrants, that so many of us began as the poor, the tired, the huddled masses, before finding our way home to American shores. We need stories that remind us that the “true” America isn’t just white; it’s white and brown and black and yellow and red and a technicolor mix of everything in between, a country full of hyphen identities and roots stretching far across the globe. It’s a legacy of diversity that infuses our cultural traditions with richer flavors, and offers us the gift of variety. And in today’s world, where globalization pushes the borders of disparate cultures closer and closer together, we – with our varied roots, our many languages and entwined histories – are uniquely placed to communicate across those borders. We are in a position not merely to tolerate that which is different, but to understand it. We are in a position to offer empathy instead of fear. That’s not something that deserves our scorn and resentment. That’s something that deserves our pride.