In Part I, I discussed the Freudian model of fetishism, phallic mothers, and their importance to Gilbert Hernandez’s Poison River graphic novel. I’ll wait here if you want to go read that piece of mindbending wisdom. Waiting…waiting… Welcome back!

________________

What the preceding has to do with the Locas roundtable, or Jaime Hernandez’s work more generally, may seem a bit distant, but it all links, fairly directly, to the primary theme of the roundtable thus far: nostalgia. Jaime’s works function nostalgically, or seem to, and are frequently about nostalgia (however one wishes to define the term) and the traffic between past and present. Freud’s account of fetishism is, in fact, an account of nostalgia as well…nostalgia for the phallic mother…nostalgia for that originary moment before knowledge of sexual difference, and before the traumatic fear of castration.

The phallic mother represents a “perfect” time, a time of wholeness and unity in a number of ways. First, it is a time when mother and son are still joined together without the interference of the father. While the child may be aware of the competition with the father, he has not yet given up the notion that he will be forever joined to the mother and that their blissful union will be eternal. It is the threat of castration that frightens the child out of these utopian beliefs, at least for boys, but the attachment of desires to the fetish is an attempt to retain such a utopia, to hold onto this perfect past even after it is already gone. To fetishize a shoe (or an athletic support-belt) is to cling to the past with the mother, and to be “nostalgic” for it.

Second, the phallic mother represents a complete and ideal “whole” human being, who has both breasts and a penis, the complete and unified being the boy imagines his mother to be before the revelation of her (and the prospect of his own) castration. When the child learns of sexual difference, he learns that none of us are “whole.” We are one gender or the other, but never both, and so, it is “natural” to reminisce and to feel “nostalgic” for such an ideal wholeness even as one pursues a replacement for it in the field of romantic love.

Again, there is no reason why we must believe in the narratives Freud provides, but it does provide a useful heuristic for understanding Jaime Hernandez’s work as well and especially the stories collected in La Perla La Loca (which includes the graphic novel, Wigwam Bam and the stories which follow). Perhaps most central and helpful in looking at these stories is the central truth of these Freudian narratives, which is that “nostalgia” here is never nostalgia for something real, but is instead nostalgia for a fantasy of wholeness which never existed. Simply put, of course, the boy’s mother was never an androgynous whole with both a penis and breasts. This is, of course, merely a fantasy the boy has (or a fantasy Freud has and projects upon the boy in his story). Likewise, the mother was never castrated. Rather, she never had a penis from the beginning. Similarly, the boy never had a direct, unmediated, love affair with his mother uninterrupted by the father. Again, this is simply an Oedipal fantasy that serves to structure the boy’s psyche, but has no basis in reality. A fetish, then, is a replacement for something that was never there in the first place, a replacement for the female phallus that Peter Rio (in Poison River) searches out, but which was never present in his own mother. It is this model of replacing an absent original that is central to Jaime Hernandez’s work in general and Wigwam Bam in particular, and which helps explain the peculiar “emptiness” at the center of his nostalgic forays.

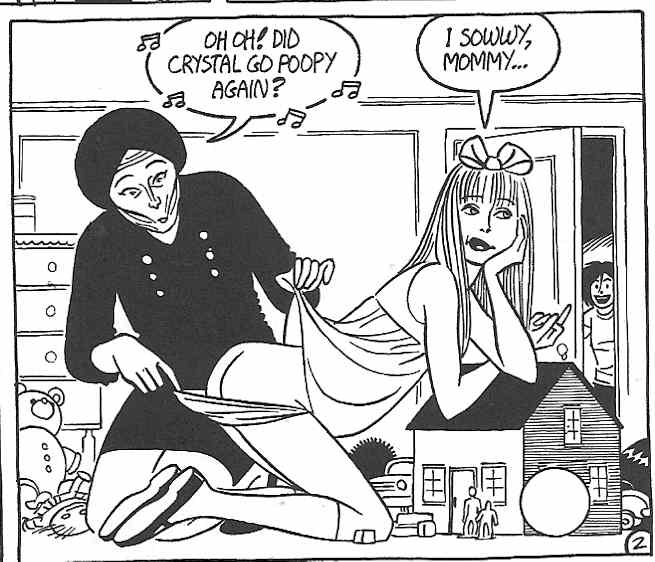

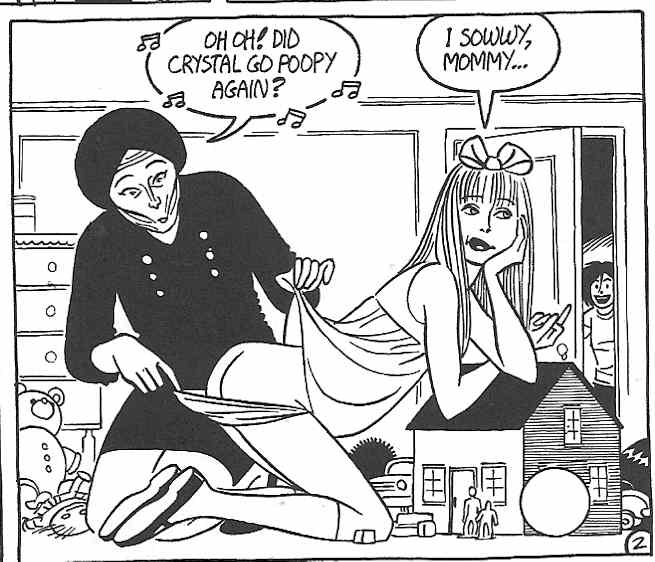

As evidence, it is perhaps worth recalling one instance of explicit sexual fetishism in Wigwam Bam, which occurs when Hopey spends a brief period couch-surfing with her friend, Jewel, in New York, after leaving another friend’s apartment. Jewel’s mother, Nan Tucker, has her own peculiar fetish, which rivals Peter Rio’s. While not fixated on a particular object, Nan pays a young woman, Crystal, to dress up as a much younger girl, and pretend to be her “baby,” allowing Nan to change her diaper, and role-play similar activities. In fact, as it turns out Nan organizes gatherings of famous TV sit-com mothers (of which she is one) who have identical fetishes and who bring their own “wards” with them. While conventional sex itself never seems to be in play in these relationships, and the girls are paid well to act their roles, the scenario certainly plays out in fetishistic fashion, particularly given the Freudian material cited in Part I.

The TV moms’ fetishization of youth encapsulates a similar kind of “nostalgia” to the kind that Freud discusses, if somewhat in reverse. Nan nostalgically attempts to recapture her own youth, both as a young mother, and as a child, paying Crystal to “act out” the wholeness and unity of mother/child relations that are central to the Oedipal scenario (if, in Freud, usually from the point of view of the child). Given Nan’s vexed relationship with her own daughter (whom she competes with for Hopey’s affection), like Freud’s version of the fetish, Nan here is nostalgic for something that never existed. With Crystal, there is an ideal union with a daughter who will always be young and obedient (because paid to perform that role), as opposed to her real daughter who is now an adult and disgusted by her mother’s behavior. In fact, it is strongly implied that these women’s entire careers on television, as sit-com mothers, is already a replacement for their own failed relationships with their daughters, and the young women they hire serve as replacements for the replacements…second order fetishes that help them to convince themselves of the original’s existence (while also disavowing it).

Here, Jaime provides a broad satire and mockery of a nostalgia for innocence and childhood, which belies the notion that Locas itself represents a simplistic foray into such nostalgia. Instead, via the logic of fetishism, Locas suggests that any such nostalgia is a longing for an absence, whether it be the mother’s phallus which never existed, or a perfect mother/child relationship that can only be simulated in sit-coms or by hiring a child not one’s own.

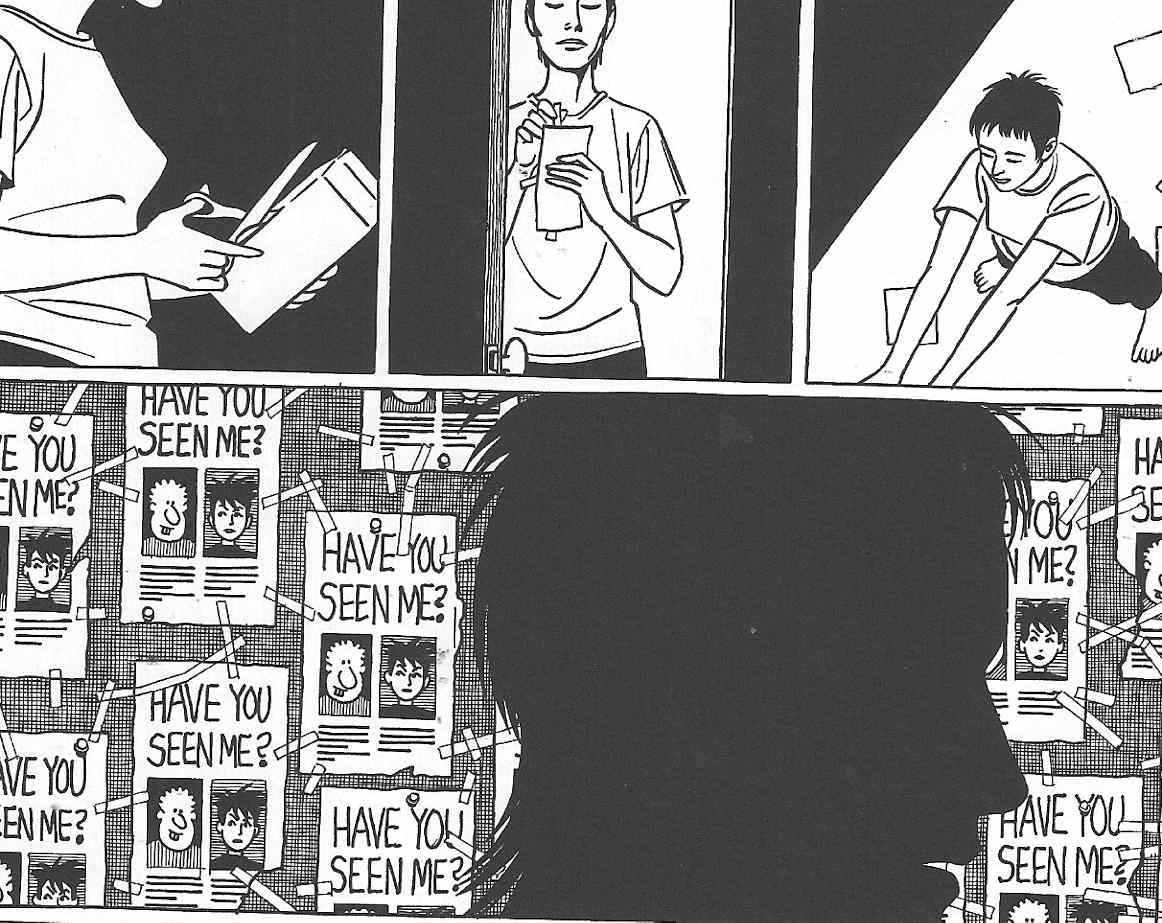

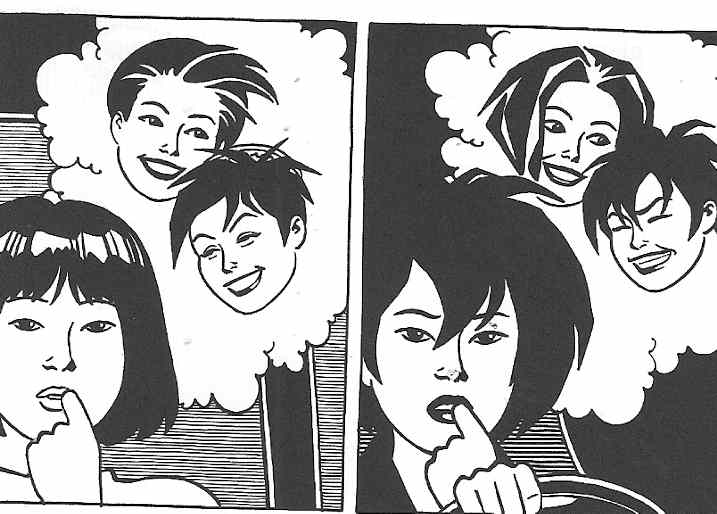

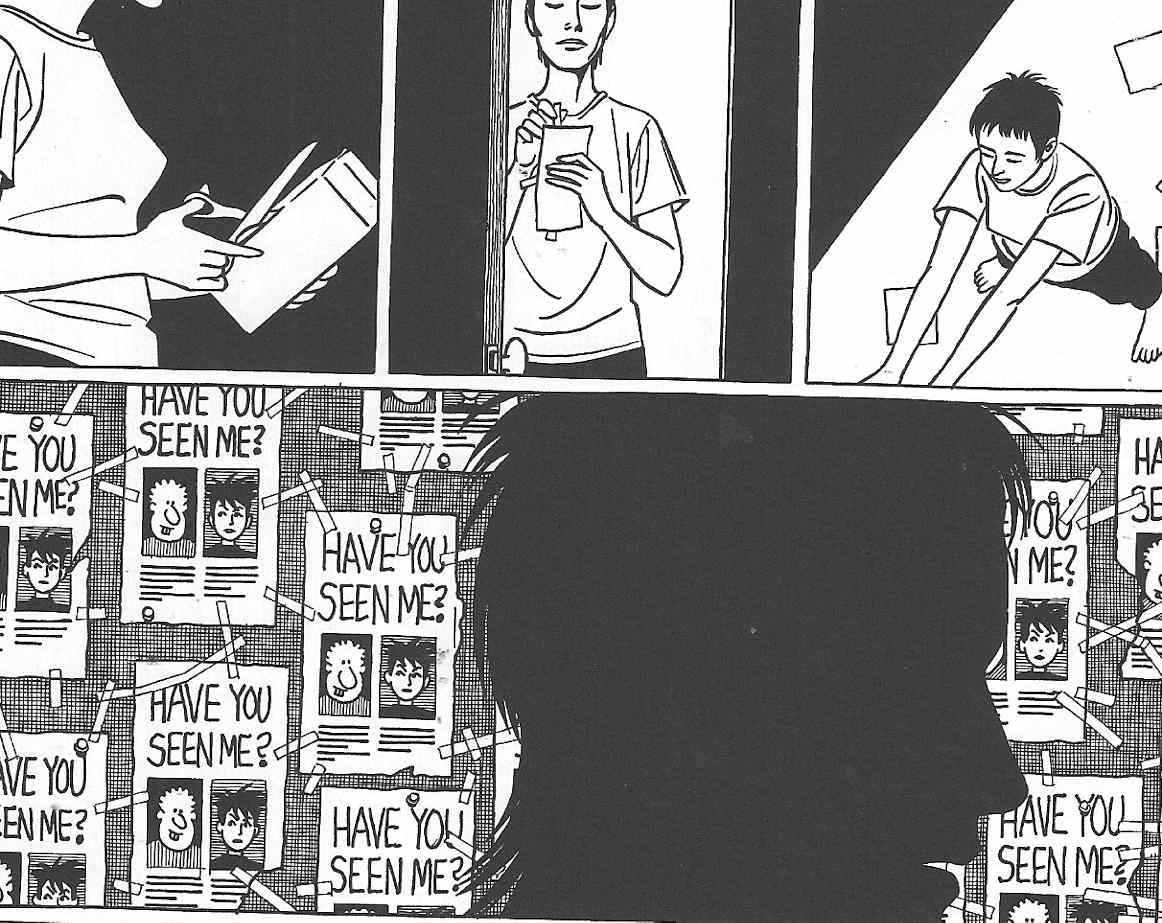

Nan Tucker’s nostalgia and desire for a perfect, originary moment of wholeness is not an isolated incident in Wigwam Bam, but is rather a synecdoche for its entire workings. As Douglas Wolk notes in his reading of WWB, perhaps the most clever formal trick deployed in its pages is the strategic absence of Locas’ most central character, Maggie Chascarillo (known also as “Perla” in the book in question). Apart from the first 14-page section of the 115 page graphic novel, Maggie does not appear in WWB and so the reader takes place in the grand search for her that is also enacted by its characters. In particular, Maggie’s childhood “punk” friends from Hoppers, spend the story looking for both Maggie and Hopey, who have traveled to New York (one in pursuit of the other). Izzy Ortiz, in particular, dealing with mental health issues of her own, becomes obsessed with the absence of Maggie and Hopey, cutting out the backs of milk cartons which picture Hopey in “Have You Seen Me” mode and taping them to her walls. Eventually, Izzy’s obsession with the missing Maggie and Hopey leads her to travel the country in search of the two friends, meeting up with a variety of Locas characters along the way.

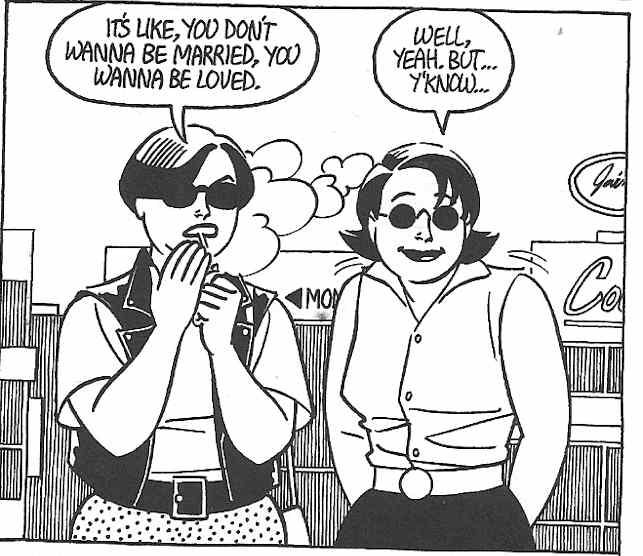

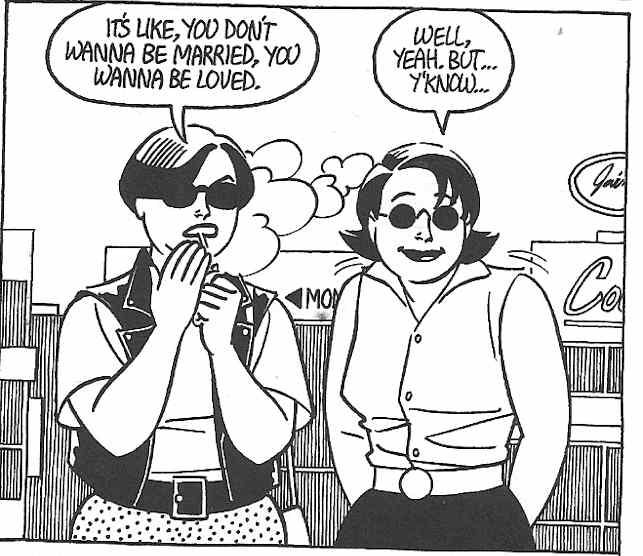

Here again, Izzy’s search is clearly an act of nostalgia. For Izzy (and Daffy, and their friends), the friendship (with benefits) of Maggie and Hopey represents a prelapsarian utopian paradise that is linked to the punk culture of which they were all a part. The punk community of their youth, or the women’s imagined vision of it, rejects dominant culture’s series of hierarchies and divisions, including those of race, gender, class, and sexuality. The punk community’s rejection of consumerist/corporate capitalism is well-established, but the concomitant image of an angry, loud, violent opposition is largely eschewed in Locas, in favor of an image of a community which is accepting, multi-racial, gender-equal, and open to non-heteronormative sexualities. Maggie and Hopey, in particular, represent both the rebelliousness of the Hoppers punks (particularly in Hopey’s case), but also its friendly, open, and forgiving face (particularly in Maggie’s case). Their lesbianism (or bisexuality) is open to interpretation but is never censured or rejected by their fellow punks, whether male or female (many of whom are also “queer.”) The blurring of gender divisions, and therefore heteronormativity, is, as discussed in Part I, part and parcel of a hearkening for the pre-Oedipal, a time before such divisions are known. The Maggie/Hopey relationship (or the memory of it) serves as a fetish for Izzy, who desperately tries to track them down and regain the utopian promise of Hoppers in its younger, punkier, days.

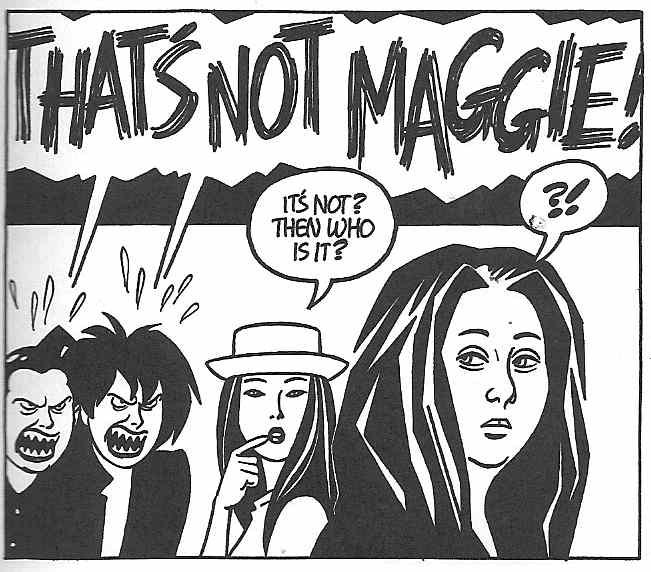

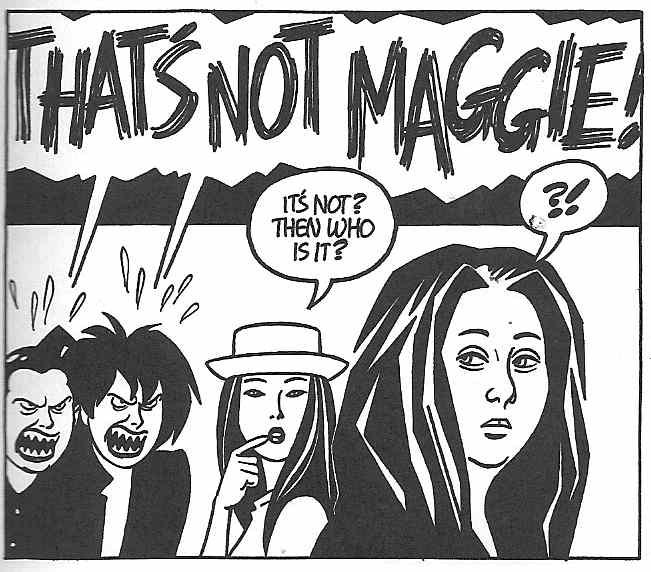

It should be no surprise, given these thematics, that among the individuals Izzy finds on her journey are both a Maggie lookalike (an explicit replacement) and a “phallic woman” from her own youth, a woman who has undergone a sex change to become a man. Likewise, it is not surprising that this “real” phallic woman fails to hold the attraction of the utopia Izzy has imagined. S/he is a failed replacement for Maggie/Hopey, just as Peter Rio’s strippers are failed replacements for his (phallic) mother.

By the time Izzy finds Maggie and Hopey, of course, they are no longer “together” despite their earlier efforts to reunite. In fact, their brief blissful attempt to reignite their friendship and recover their youth is sabotaged by the racial difference that is rarely of explicit emphasis in the previous stories that take place in Hoppers. When Maggie is mocked at a party for being Mexican, she seeks solace in Hopey, who is less than sympathetic. When it becomes clear that Hopey, who is half Colombian, can “pass” for white, a racial divide opens between the two women that, perhaps, had previously existed, but which had gone unmentioned. Hopey’s casually homophobic reference to “art fags” (despite her own sexual orientation), further cements the ways in which the nostalgia for the “perfectly punk” Maggie/Hopey relationship is misplaced in “real world” New York, which, despite its cosmopolitanism, is rife with racism and homophobia.

Indeed, later in the story, we learn that the Maggie/Hopey relationship is itself merely a replacement for, or copy of, Maggie’s first “punk” relationship, with her best friend Letty, who introduced her to punk music before dying in a car crash. In a telling diary entry, Maggie writes, “I hope Hopey never dies in a car crash. Lightning only strikes twice once, y’know” (115). Hopey is here explicitly framed as a “replacement” for Letty, a fetish which covers up an absence, while attempting to replace the “wholeness” of the Maggie/Letty relationship, though Maggie worries that the replacement itself cannot be replaced.

Within this context, Ray D, Maggie’s next serious relationship (one which “culminates” in the recent Love Bunglers arc), serves as a replacement for Hopey, who herself is a replacement for Letty. Within a Freudian logic, Letty can only be a replacement for the mother (or the mother’s phallus), and Maggie’s expulsion from the maternal family home to live with her Aunt Vicki in Hoppers as a youth might substantiate such a reading. At the same time, the important point here is that regardless of the idealization of the Maggie/Letty relationship, it is clear that such idealization is a mirage, a hope for something which, like the mother’s phallus, never existed to begin with. The Hopey/Maggie relationship is, after all, similarly idealized, but is revealed to have many cracks in its façade.

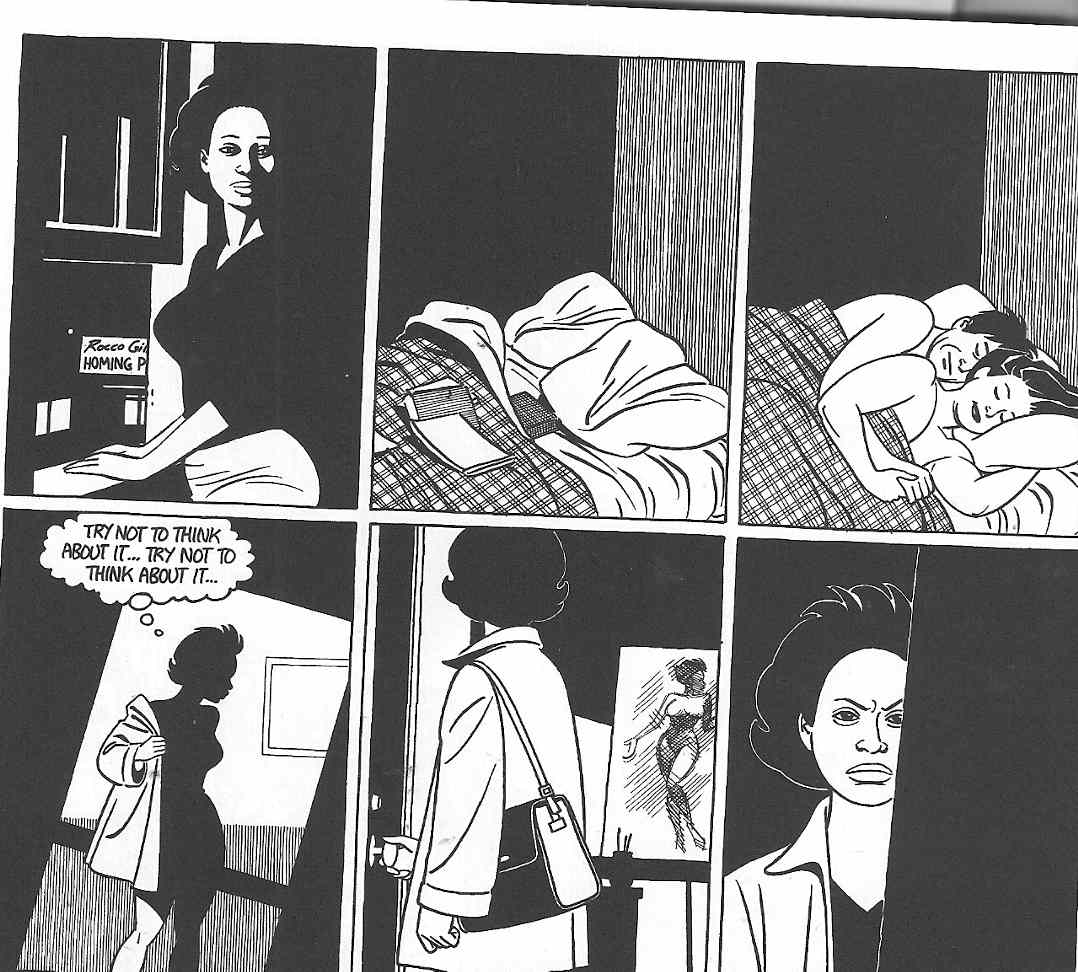

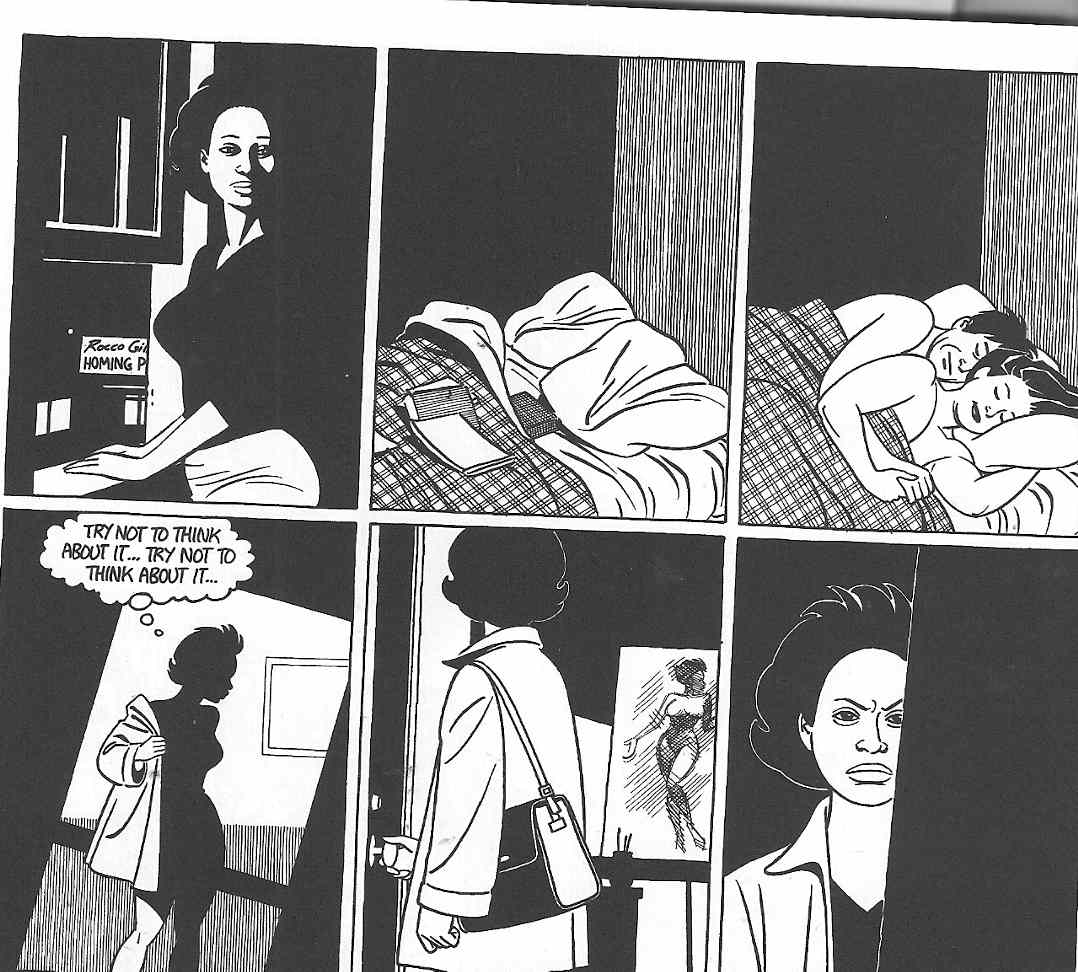

Similarly, Ray D.’s relationship with Danita Lincoln is characterized as a replacement for his earlier affair with Maggie. In particular, Danita’s confidence in the level of Ray’s commitment vacillates. She worries both that she is merely a “sex object” for Ray and that he cares not for her as an individual, but as a Maggie substitute, even going so far as imagining Ray in her own bed, cuddling with his ex-girlfriend. Danita’s fears about her own “fetishization” (her transformation into a sex object and Maggie replacement) is played out in multiple scenarios. She serves as a nude model for Ray’s drawing/painting and as a stripper at the local club, Bumpers. Her friend Rocky suggests that Ray sees her only as an object, when looking at Ray’s drawing, as if he were one of the members of the strip-club audience. At that moment, Danita, who had initially been flattered by Ray’s appreciation, begins to wonder to what degree she is just a body, filling the space recently left empty by her predecessor. Likewise, where she once saw her stripping as an empowering experience of agency, she now begins to see herself through the eyes of her audience, as one of a procession of naked bodies on a stage, objects which occupy the same space, replacing each other at regular intervals.

In this scene, Wigwam Bam examines itself as well. Ray too becomes a replacement of sorts, not only of Hopey in Maggie’s life, but also of someone “real,” Jaime Hernandez himself. When Rocky accuses Ray of objectifying Danita, it functions as Jaime Hernandez accusing himself of objectifying her, and his other female characters for good measure, for it is he who really draws naked pictures of women, both for his own pleasure and that of his mostly male audience. Again, as in the case of his brother, Gilbert, the fetishizing and objectification of women is here brought up against a moment of self-examination and an acknowledgment that from Danita’s point-of-view, she cannot merely be a body for the pleasure of the male gaze or a simple replacement for the superior/utopian relationship that preceded it, even if that relationship never really existed in its ideal form. Danita’s self-conscious worry is, indeed, a sign of her subjectivity. Her vulnerability and determination make her in some ways similar to Maggie, but far from identical to her. Her assertion of her own subjectivity is a tacit critique of the practice of fetishizing people, of transforming subjects into (replacement) objects for the purposes of sexual pleasure, and it comes as no surprise when she leaves Ray, a tacit rejection of her objectification at both his, and Jaime’s hands.

The encounter/conflict here between Danita-as-object/replacement/fetish and Danita-as-subject/original here sets up the ways in which WWB and its immediate sequels take things a step beyond the fetishism on display in Poison River. In Poison River, there is a focus on fetishism-as-utopian-fantasy and then disillusionment with that fantasy. That is, the fantasy of reunification with the phallic mother is revealed to be a fantasy and the book closes on a note of disillusionment where everything is corrupted, gender divisions are enforced, and a bloodbath ensues. In the Perla La Loca stories, simple disillusionment is not enough, however, and Jaime pushes the narrative forward into a more “realistic” engagement with utopian premises.

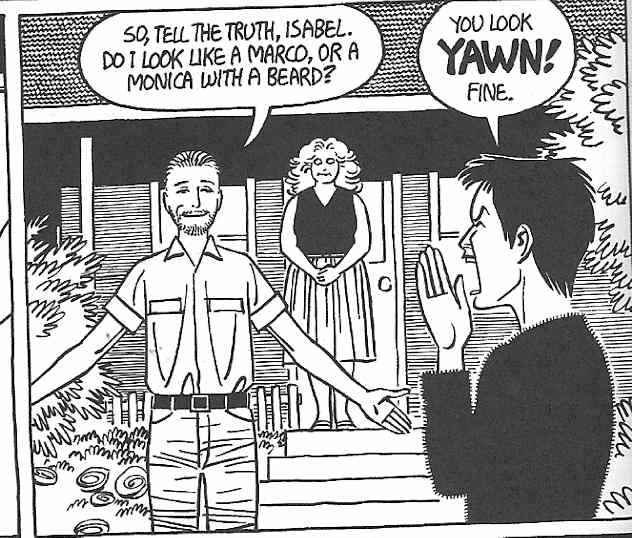

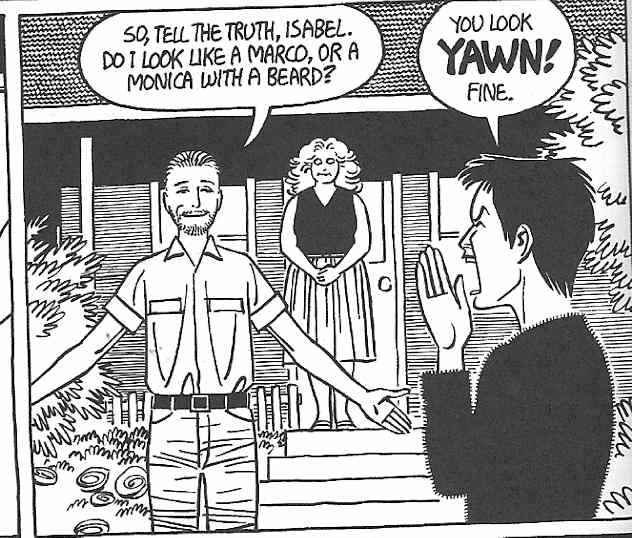

As Danita’s introspection suggests, while “fetishism” may, in some ways, envision a utopia wherein gender divisions, racial divisions, and divisions on the basis of sexual orientation do not obtain, they do so on the basis of a backward-looking fantasy to the pre-Oedipal. In such a fantasy, no individual in the present is fully acknowledged or accepted for their own sake, since they are always inevitably viewed as a replacement for someone else. As we have seen, Hopey functions as a replacement for Letty (and Ray for Hopey), while there are also a seemingly neverending series of Maggie replacements as well. In addition to Danita, Marcia/Marco, and the Maggie lookalike, we learn in “We Want the World and We Want It Bald,” for instance, that Hopey’s brother Joey’s girlfriend, Janet, is also a Maggie replacement, and plays a role in the sexual fantasies/fetishes that Joey inflicts upon her. In all of these cases, however, if one reads the stories “realistically,” as opposed to merely as an instantiation of Freudian theory, the danger arises of reading individuals as merely replacements for one another, as “fetish objects” as opposed to as autonomous subjects.

In fact, Jaime uses the pervasive theme of replacements and fetishes in order to probe and reject the tendency we all have to use people in our lives as “objects” for our own pleasure (fetish objects), as opposed to as subjects with autonomy. Danita may function as a replacement for Maggie for Ray (though this is somewhat questionable), but for herself she has autonomy. Likewise, Hopey wonders what Janet “gets out of” her fetishized relationship with Joey, when she seems to serve merely as a stand-in (again) for Maggie. Even Maggie herself is in danger of falling victim to a kind of objectification if we are content to view her simply as a “symbol” of phallic motherhood (a figure that remains an idealized symbol of wholeness, unity, innocence, and purity), and not as a complex, fallible individual.

This theme of objectification plays into Locas’ parallel exploration of the problems of capitalist culture to which punk is configured as an alternative. As Marx notes in The Communist Manifesto, capitalism reduces all relationships to “the money relation” (659), wherein individuals view other individuals not as human beings (subjects), but as a means to their own acquisition of wealth (objects), a weigh station on the way to the acquisition of capital. It is for this reason that Marx can articulate the existence in society of “commodity fetishism,” in which people put outsized importance upon specific commodities. If money is the only value in society, it should be no surprise that “pleasure” can only come from them. If one combines Freudian and Marxist logic, then, to fetishize a commodity (or object) is both to imagine a world wherein there are no divisions (and therefore no exploitations) and to value a world wherein those exploitations are inscribed upon the very object being fetishized. As a “replacement” for the phallic mother, the fetish object symbolizes a perfect “whole” world devoid of divisive qualities, while, as a commodity, it carries the trace and history of endemic class exploitation. The contradiction brings to our attention the limits of thinking through the logic of Freudian fetishism. While, symbolically, the “objectification/fetishism” may represent a challenge to the race, class, and gender divisions in a society, in social practice, to treat an individual as an object/fetish is to treat them, á la Kant, as a means to an end, as opposed to as an end in themselves.

All of this is clear in Danita’s rejection of her role as Maggie’s replacement, as well as in her eventual rejection of her role as a stripper. The stripper role is complex in the story, as Danita clearly feels like it gives her agency and power, but even though this is the case, it also positions her as the object of the male gaze, a position she is increasingly uncomfortable in occupying. In either case, however, it is interesting that, despite her role as the object of the gaze (as nude model for both Ray and the reader, and as stripper for both Bumpers and the reader), she never relinquishes her subjectivity, insisting that while she may be the object in the eyes of the “other,” she nevertheless remains a “subject” to herself.

Increasingly, the notion that all individuals are both subjects and objects becomes thematized in Locas, not merely for Danita, but for others as well. Maggie, in particular, occupies a similar position, when, in Chester Square she is turned into an accidental prostitute. Stranded without money and without means of transportation, Maggie twice “sells herself” sexually, becoming an “object” in the capitalist economy, and tacitly rejecting her role as symbol of the classless Marxist/punk utopia.

If punk culture rejects the ways in which the dominant culture puts everything up “for sale,” then it undoubtedly rejects the notions that individual subjects can be seen simply as “objects.” Prostitution, on the other hand, is, in many ways, the ultimate symbol for capitalism. In prostitution, almost literally, “everything is for sale,” as it is in capitalist society more generally. Despite the logic of the prostitution=capitalism analogy, however, Jaime rejects the most extreme of its ramifications in “Chester Square.”

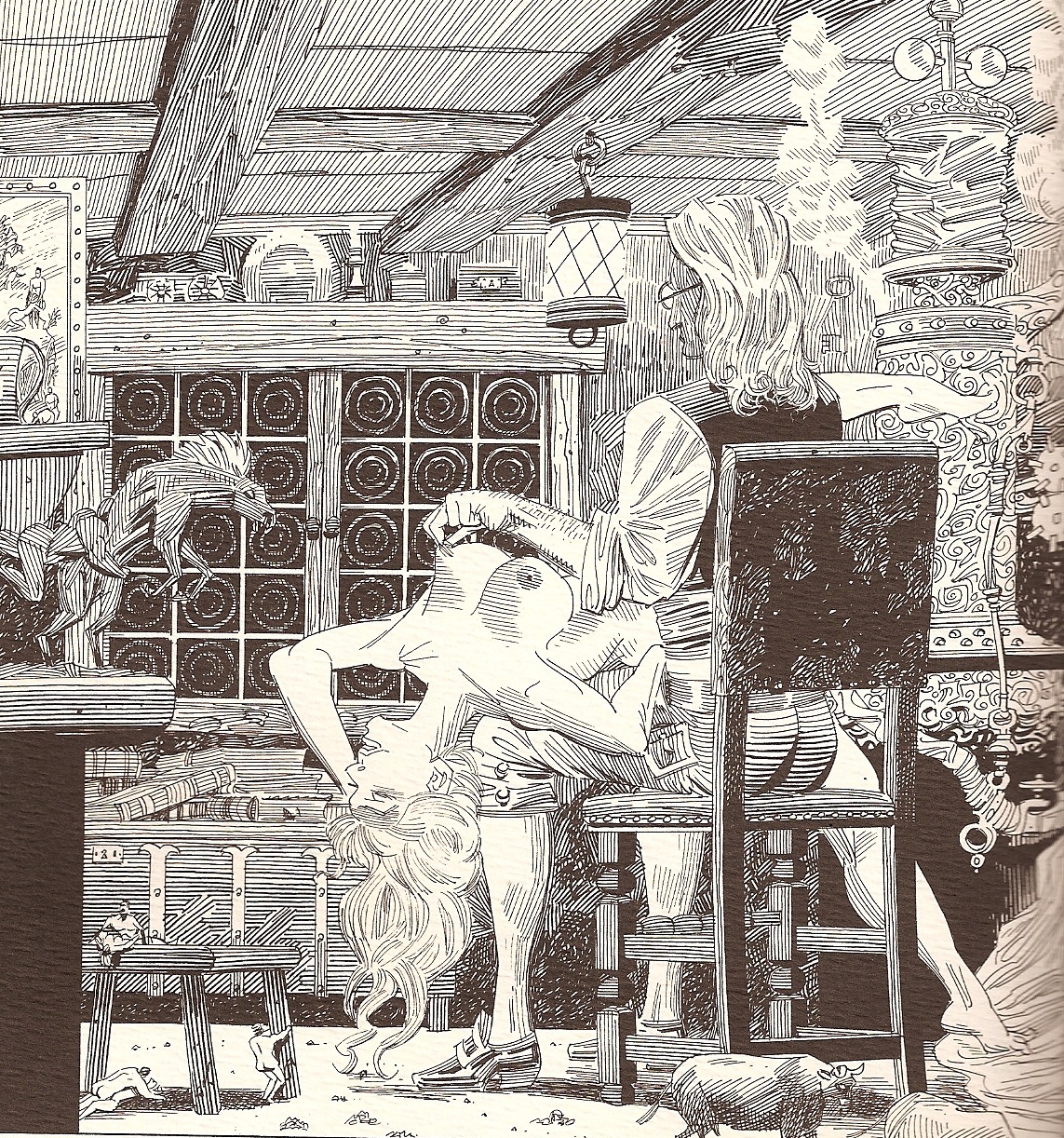

In the pair of panels pictured here, we see a clash of “Maggie as object” and “Maggie as subject.” In the first panel, she imagines herself as the prostitute she eventually (if momentarily) becomes, “posing” as a sex kitten who invites her own “use” by the men just outside the door. It’s clear though that this self-fetishization is simply a pose, or fantasy, when she is surprised by the knock at the door. Her humorously exaggerated response reveals other facets of her personality, beyond just as an object for sexual use. The juxtaposition of the two panels reveals two women juxtaposed, one of aggressive sexuality and the other of an exaggerated modesty. The fact that the two women are actually one at two different moments in time reveals a complex individual, who, when beyond closed doors, displays contradictory and complicated impulses.

Of course, Maggie is not, here, exactly “behind closed doors.” Rather, her naked body (like Danita’s) is on display for the reader, and in the first panel, she looks at us, inviting us to “use her” as we will sexually. The second panel, however, deflates the pornographic quality of the first, reminding us that behind every “objectified” woman is also a subject and behind every prostitute who is transformed into a commodity is a woman who may be embarrassed, humiliated, or even, simply, modest in her “real” life.

Maggie’s impulse toward subjectivity (again, like Danita’s) and her resistance to her own commodification, makes her reject the man, Enero, who in subsequent pages mistakes her for a prostitute, even though she was willing to sleep with him for free. Ironically, however, when she invites the security guard in for a sexual encounter that is not supposed to be a monetary transaction, he makes the same mistake, leaving her money on the nightstand. Though mortified, the money allows Maggie to escape the Square, taking a bus to her Aunt Vicki’s, where she eventually tells her friend Gina about the incident, noting that “I really didn’t feel bad about doing it. Like it was no big deal” (153). Though she eventually backtracks on this claim, calling herself a “whore…trollop, floozy, harlot, doxy, cocette, chippie” (153), it is clear that while Maggie (and the reader) might expect her commodification, or objectification, to rob her of her subjectivity, in fact, she leaves the encounter in much the same way that she entered into it, as a complex woman who is not defined by this single act. In fact, she only begins to see herself as a “whore” when she tells someone else about it, viewing herself not from the inside (as subject), but from the outside, through Gina’s eyes. Doing so allows Maggie to view herself as she initially views the prostitute, Ruby, who she is, for a time, mistaken for, not as a human being, but as a commodity.

The episode, then, like Danita’s posing and stripping, refuses a simple subject/object dichotomy, where there is an “original” subject of fantasy (the phallic mother), and a series of objects that replace her (fetishes). Instead, the replacements themselves are subjects, who may be objectified by society, or the individuals they interact with, but who cannot be reduced to such a function. Concomitantly, the book suggests that the ideals of acceptance of differences of race, gender, and sexual orientation are not proposed simply as symbols of a mythological or utopian punk past, but are instead cast forward as a goal for society that we must attempt to achieve in the present. When Maggie and Hopey reunite at the close of La Perla La Loca (or at the close of the original run of Love and Rockets), they do so only after they separate over issues of racial discrimination and homophobia. That is, if they are to move forward and reunite, they must overcome such differences, rather than “pretend they never happened” as fetishism (in Freud’s account) attempts to pretend that castration never occurred.

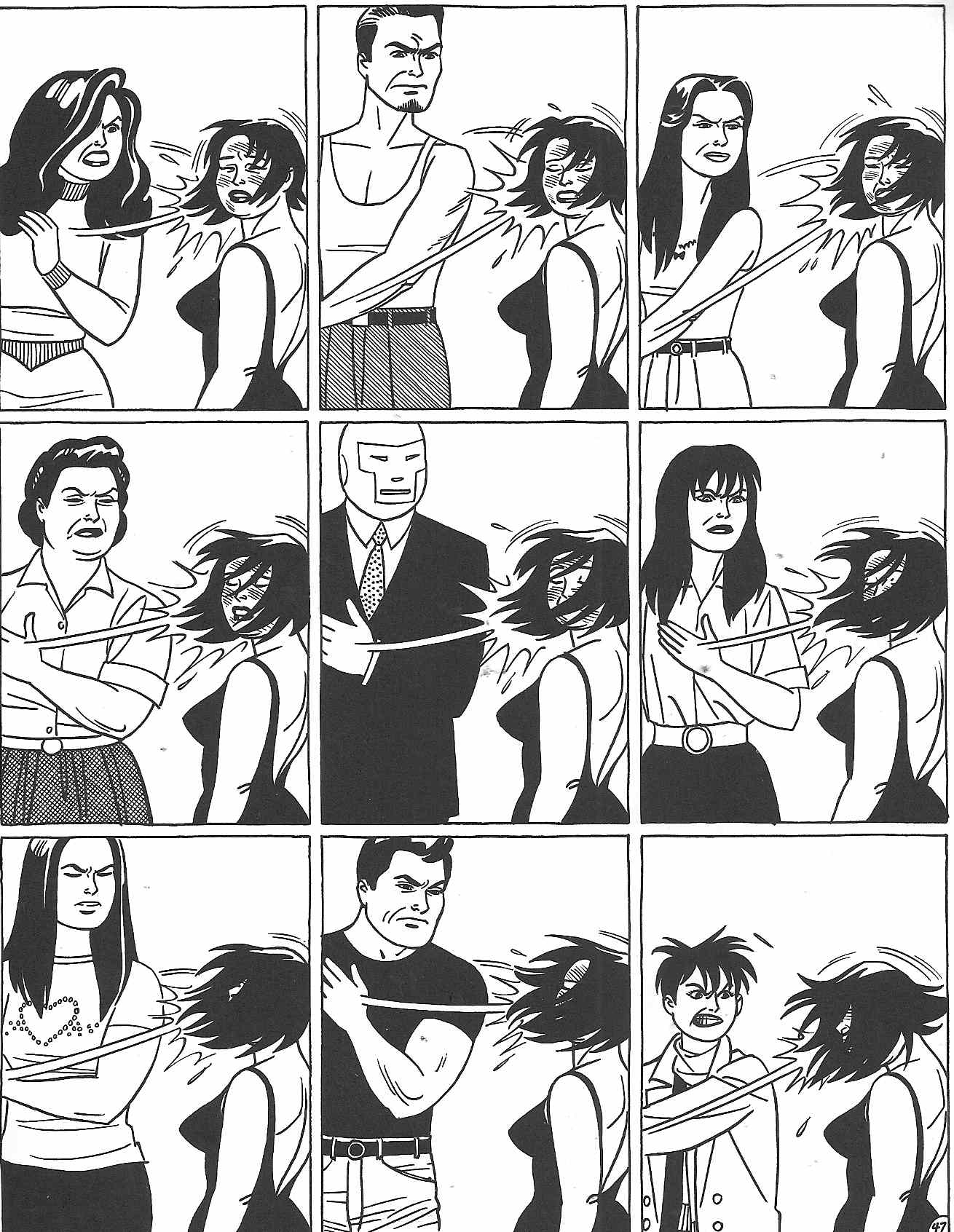

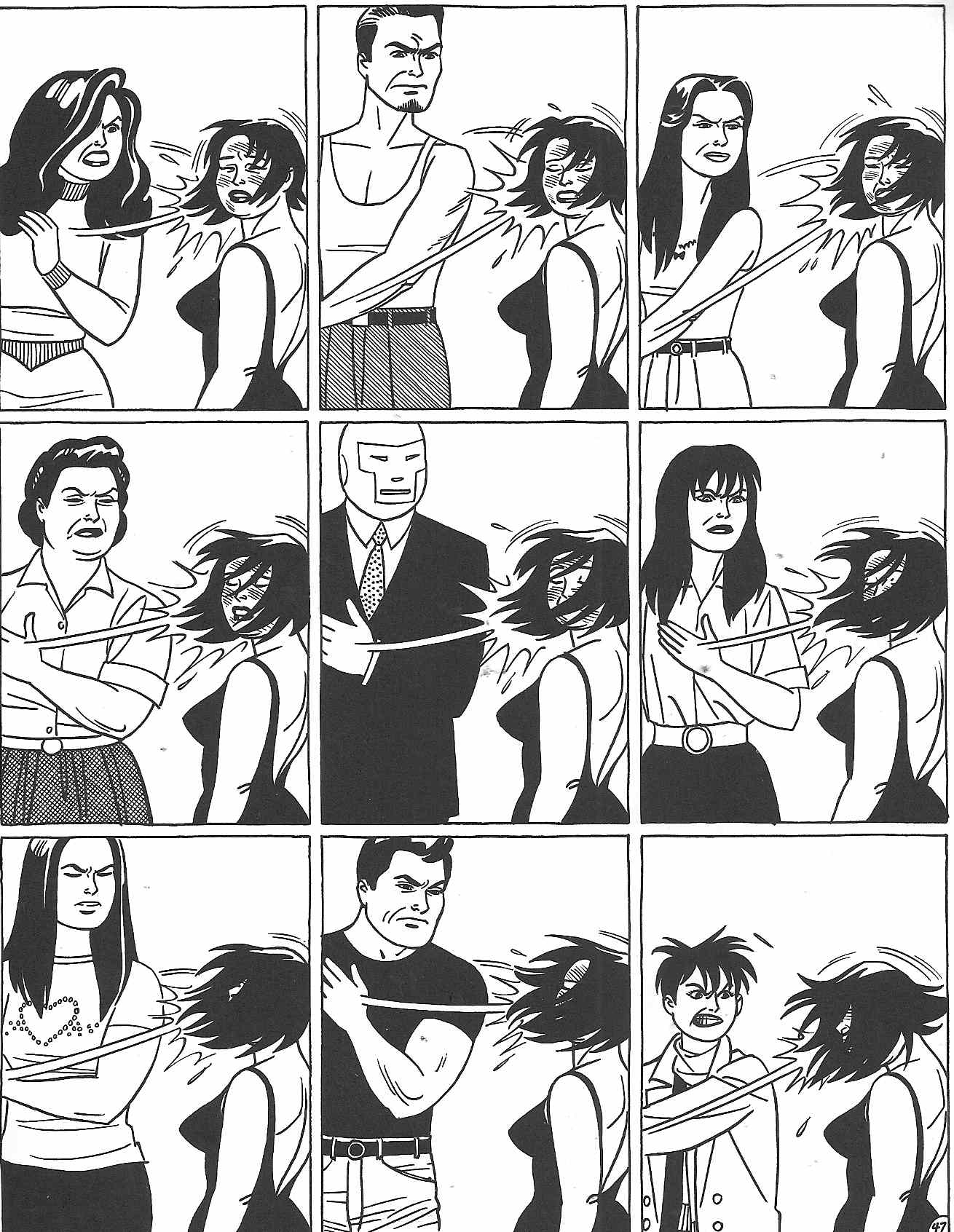

Again, this is explicitly emphasized in the closing pages of “Bob Richardson,” wherein Maggie has a dream/fantasy that Hopey never left her for the East Coast tour with her punk band which provides the impetus for much of the action of Wigwam Bam. Like the fantasy of the phallic mother, Maggie’s dream is a fantasy of wholeness and unity that predates all of the divisions that infect their relationship in the weeks, months, and years to come. Instead, however, Maggie “wakes up,” to be “slapped in the face” by all of the people she’s hurt in the interim (or whom she believes she has disappointed). She can only move forward, here, by rejecting her “dream” of a perfect past untainted by her own errors and those made by those around her.

The rejection of fetishism-as-nostalgia is articulated clearly at the close of Wigwam Bam, wherein Nan Tucker hires thugs to brutally beat both Crystal and Hopey as a warning to cover up the beating (and possible death) of one of the other fetishized play-acting “babies.” There, a fixation on a supposedly utopian “childhood” is explicitly coded as “dangerous,” resulting in a rude awakening to the realities of a world wherein self-interest trumps all. Though Nan and the sit-com mothers fantasize about a perfect union with their fetish “children,” in the end such a fantasy cannot stand up to naked self-interest, as they are willing to sacrifice (and brutalize) the fantasy to protect themselves. Wigwam Bam is not, however, the end of the story, and the brutality of exploitation and cover-up we see there (and also in Poison River) tell only part of Jaime’s story.

In the aftermath of the disillusionment of Wigwam Bam, Maggie, Hopey and their surrounding cast of characters consistently reject the notion that “living in the now” must simply mean the objectification and commodification of others, and the abandonment of a more utopian community which, it turns out, was always a fantasy to begin with. Instead, they search for a way to love and accept others’ subjectivities even after the corruption and commodification endemic to capitalist society. Even after Maggie is commodified as a prostitute, she moves forward in an attempt to make a better world for herself and her friends. Likewise, when Maggie is arrested at the close of “Bob Richardson,” Hopey abandons her self-interest in order to join her in the police car. Similarly, when Gina intuits her friend Xo’s need to win a wrestling match, she chooses to throw the match to her, despite the fact that she knows she will not get the reward for doing so that she wishes (159). Perhaps most tellingly, despite the abuse she has sustained at her hands, Maggie seeks out the regular Chester Square prostitute, Ruby, in order to make amends and to treat Ruby as a human being: a subject, not an object, despite her profession.

As Ruby herself articulates, then, the ultimate goal of the “love” of Love and Rockets is then a “love” of mutuality, openness, and intersubjectivity in the present, and in the real world, not a nostalgia for a utopian past that never existed in the first place. While there is certainly the notion in Locas that our present world is one of exploitation and objectification, there is also offered the possibility that even within that world, we need not see others merely as “means” for our own ends. When Hopey and Gina sacrifice themselves for the good of their friends, we are, perhaps, free to read those actions as self-interested, but it perhaps makes more sense to seem them as acts of love. Maggie’s variably successful efforts to make amends for her past behavior in the closing pages of “Bob Richardson,” both with Ruby and others, similarly indicates the importance of looking forward, not back.

Continually, then, as several of the other entries in the roundtable make clear, Jaime revisits the past in the ongoing Locas serial not to revisit a sentimentally idealized ür-time but to expose the ways in which the past was never like that. As in the Freudian account of fetishism, the phallic mother never existed, and so our attempts to return to her, or to an idealized past, are merely a series of self-deceptions. The recent storyline of Browntown, in particular, serves to remind us that the past is not a place free of exploitation, division, and oppression and is therefore not something to be nostalgic for, or to fetishize. Rather, as Jaime’s characters age inexorably along with us, we are reminded that if we want such a place to exist, we must work for it in the present, and hope for it in the future.

_____________

The Locas roundtable index is here.

_____________

More Works Cited

Hernandez, Jaime. La Perla La Loca. Seattle, Wa: Fantagraphics Books, 2007.

Marx, Karl and Friedrick Engels. “From The Communist Manifesto.” 1848, 1888. The Norton

Anthology of Theory and Criticism, Second Edition. Eds. Vincent Leitch, et. al. New York: W. W. Norton, Inc., 2001, 2010. 657-660.

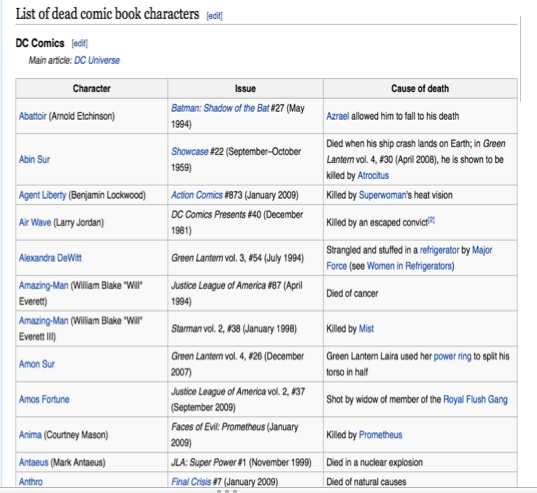

In a lecture titled, We are who we choose to be,” Eric Berlatsky remarks on the strange construction of time in superhero narratives and the way it undermines any sense of moral responsibility. Heroes make choices, and choices have consequences; but in superhero stories, Berlatsky notes, “rarely, if ever, are these consequences permanent.” He provides several examples: the death and return of numerous heroes (most notably Superman), Peter Parker’s repeated reversion to high school, marriages that do not end but are simply forgotten, Superman rewinding the world to save Lois Lane. Sometimes these miracles are achieved through time travel, sometimes heroes are literally resurrected. Sometimes such “events happen . . . ‘in the continuity’ of the basic Marvel or DC universes,” sometimes “in ‘alternative continuities’ in the comics,” and sometimes in “other media like video games, television shows, and movies.” Occasionally, the existing continuity is scrapped altogether and a new one introduced. But whatever the mechanism, “all of [them] continually elaborate new paths forking.”

In a lecture titled, We are who we choose to be,” Eric Berlatsky remarks on the strange construction of time in superhero narratives and the way it undermines any sense of moral responsibility. Heroes make choices, and choices have consequences; but in superhero stories, Berlatsky notes, “rarely, if ever, are these consequences permanent.” He provides several examples: the death and return of numerous heroes (most notably Superman), Peter Parker’s repeated reversion to high school, marriages that do not end but are simply forgotten, Superman rewinding the world to save Lois Lane. Sometimes these miracles are achieved through time travel, sometimes heroes are literally resurrected. Sometimes such “events happen . . . ‘in the continuity’ of the basic Marvel or DC universes,” sometimes “in ‘alternative continuities’ in the comics,” and sometimes in “other media like video games, television shows, and movies.” Occasionally, the existing continuity is scrapped altogether and a new one introduced. But whatever the mechanism, “all of [them] continually elaborate new paths forking.”