This first appeared on Comixology.

__________________

Ernest Hemingway is one of those writers I return to again and again, and each time I like him less. When I was an adolescent, I found the strong, silent protagonists mouthing stark declaratives profound, or at least engaging. The older I got, though, the less patience I had for the tired modernist schtick. “I cannot say what I feel. But it is deep. And potent. And involves fishing.” Yeah, whatever jack. I prefer authors who have thoughts complicated enough to require the occasional dependent clause, so I’ll be over here reading Jane Austen, if that’s okay with you.

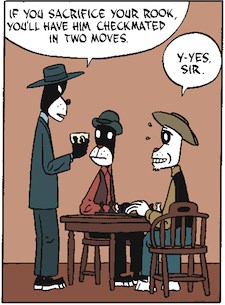

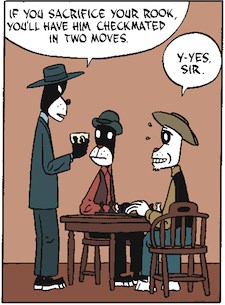

I certainly prefer Norwegian cartoonist Jason to Hemingway. For one thing, Jason doesn’t hate women, as far as I can tell. And for another, his new book of short graphic stories, Low Moon, has a bunch of clever touches that made me chuckle out loud. The story “Proto Film Noir,” for example, is “proto” because it’s about sexual jealousy and betrayal amongst cavemen (or cave-anthropomorphic –animals, to be more precise.) “Low Moon” features wild west desperadoes who settle their differences not by dueling, but by playing chess.

I certainly prefer Norwegian cartoonist Jason to Hemingway. For one thing, Jason doesn’t hate women, as far as I can tell. And for another, his new book of short graphic stories, Low Moon, has a bunch of clever touches that made me chuckle out loud. The story “Proto Film Noir,” for example, is “proto” because it’s about sexual jealousy and betrayal amongst cavemen (or cave-anthropomorphic –animals, to be more precise.) “Low Moon” features wild west desperadoes who settle their differences not by dueling, but by playing chess.

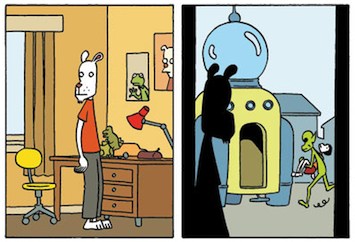

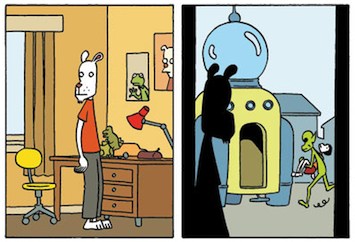

Still, it’s no accident that Ernest shows up as a character in one of Jason’s earlier graphic novels — the two definitely share some avant-garde common ground. Jason’s graphic style has a Hemingwayesque flatness. His animal protagonists lack both pupils and varied expressions; they’re all indistinguishably deadpan, all the time. The style overall is an approximation of Herge’s clear-line approach, but without Tin-Tin‘s detail or fantastic settings. Most of the backgrounds here are skillfully rendered, but sparse; some bushes, a horizon line, or, often, just a primary color. Even the flora of an alien land, in Jason’s hands, seems determinedly matter-of-fact; a space-flower is drawn as a simple, almost unadorned circle, which spits out plain, sperm-shaped seeds in a ragged, unassuming burst. One of Jason’s usual expressionless characters watches it — well, expressionlessly.

As this indicates, Jason’s stories, like his pictures, are resolutely stripped of filigree. There’s no text boxes, and often not a lot of words. Open to any page and you’re likely to find some blank-faced animal staring meaningfully at something or other. The narratives unfold with a bleak, unexplicated inevitability. In “Emily Says Hello,” a hit man reports to his female employer on a series of successful murders, in return for which he receives an escalating series of sexual favors. Then things end badly. In “Proto Film Noir,” guy and gal meet, fuck, and kill gal’s husband…repeatedly, because he keeps coming back form the dead to have breakfast. Then things end badly. In “You Are Here,” a woman is abducted by aliens; her husband spends the rest of his life building a spaceship while her son grows up, gets married, gets divorced, and eventually joins his dad seeking her in the vastness of space. Then things end badly. And also poignantly.

There’s no questioning Jason’s skill as a cartoonist; the seamless ease with which time telescopes in “You Are Here” is both lovely and impressive. Yet that mastery can also be alienating. My least favorite story is the most formally complicated: the cutely named “&”. It involves two narratives. In the first (on the left-hand pages) a man’s mother is dying. He has to pay for an operation, so he performs a bumbled, slaptick burglary, finally gets the money for the operation…and his mom dies anyway. In the second (on the right hand pages) a guy proposes to a woman, discovers she has another fiancée, and kills him. Then she gets another fiancée, and our anti-hero kills him too. And so forth, until she agrees to marry the anti-hero…but hangs herself on their wedding night. The last panel of the comic is the bereaved son and the bereaved husband sitting at a bar, where they exchange the requisite empty glance.

And, indeed, that’s where all the stories seem to end. In silence, gazing at the black absurdity of life. The smooth, empty surface is meant to evoke a deep profundity. But is it deep to reflexively gesture towards the modernist emptiness? Or is it just glib? Silence can contain meaning, certainly, but when it’s the same silence and the same meaning, it starts to get a little tiresome. Hemingway and Jason are laconic, in other words, not because they have a lot to say, but because they don’t.