There are no outrageous surprises on the collated Eurocomics list (though individual choices, of course, are more idiosyncratic). Rather, the critics who participated in the poll chose works which (a) have been translated into English, (b) have been canonically sanctioned as works of influence and merit by important critics, and/or (c) span the major periods of Eurocomics production. Perhaps a good way to discuss such a diverse group of books is to pigeonhole them into chronological periods, like so:

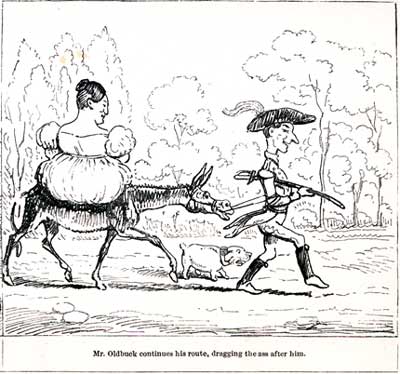

The Origin: The comics of Rodolphe Töpffer (published in Switzerland between 1833 and 1846). Töpffer’s status as the inventor of the comic book, and as the format’s first accomplished artist, was solidified by David Kunzle’s Töpffer biography (2007) and the Kunzle-edited collection Rodolphe Töpffer: The Complete Comic Strips (2007). These resources certainly made it easier for me to teach Töpffer, and learn to appreciate him myself. When I first read The Story of M. Jabot (1833), and noticed how Töpffer repeated words and images every time Jabot was trying to recover from a humiliating incident, I laughed out loud. Not bad for a comic book almost 200 years old.

The Classics: The Adventures of Tintin albums by Hergé (published in Belgium and France between 1930 and 2004); Astérix the Gaul by René Goscinny and Albert Uderzo (published in France in 1961); the Moomin books and comic strip by Tove Jansson (published in Finland between 1945 and 1993); and the Corto Maltese albums by Hugo Pratt (published in Italy and France between 1967 and 1992).

Boy reporter Tintin remains amazingly popular, influential enough to spawn both the upcoming Steven Spielberg / Peter Jackson Adventures of Tintin blockbuster film, and such alt-comics emulators of Hergé’s visual style (called la ligne claire, the clear line) as Chris Ware and Jason Lutes. Tintin’s worldwide popularity remains unsullied by Hergé’s own collusion with the Nazi occupiers of World War II Belgium, as discussed in Pierre Assouline’s Hergé: The Man Who Created Tintin (1998; first English-language edition 2009).

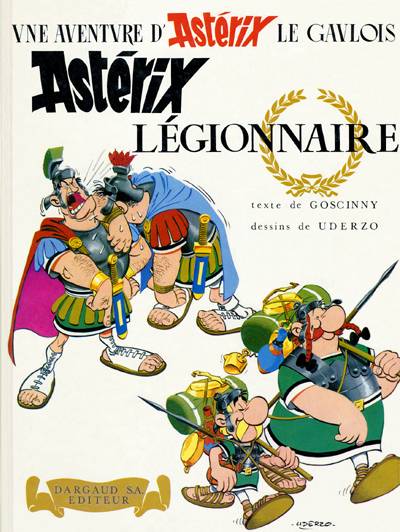

Astérix is likewise part of the canon, albeit one drawn in a knockabout bigfoot style rather than in la ligne claire. Readers everywhere recognize Astérix and his sidekick Obelix, and probably learned most of their knowledge about Rome and the Gauls from Goscinny and Uderzo. It’s interesting that the majority of HU critics chose the first Astérix volume, Astérix the Gaul (1961), as their choice; personally, I prefer the albums from the mid-to-late 1960s, like Astérix the Legionary (1967). If you haven’t read any Astérix yet, though, maybe you should start from the beginning — and stop before Astérix and the Great Divide (1980), when Goscinny dies and Uderzo takes over the writing.

Astérix is likewise part of the canon, albeit one drawn in a knockabout bigfoot style rather than in la ligne claire. Readers everywhere recognize Astérix and his sidekick Obelix, and probably learned most of their knowledge about Rome and the Gauls from Goscinny and Uderzo. It’s interesting that the majority of HU critics chose the first Astérix volume, Astérix the Gaul (1961), as their choice; personally, I prefer the albums from the mid-to-late 1960s, like Astérix the Legionary (1967). If you haven’t read any Astérix yet, though, maybe you should start from the beginning — and stop before Astérix and the Great Divide (1980), when Goscinny dies and Uderzo takes over the writing.

Although not as well-known in the United States as Tintin or Astérix, Tove Jansson’s Moomin comic strips and children’s books have been wildly popular during the last 60 years in Finland, Sweden, Europe, and elsewhere. (A far-flung example: New Zealand alt-cartoonist Dylan Horrocks has been a world-class Moomin fan since his early childhood.) Today, North American comics readers have come to love the oddball characters and storybook milieu of Moomin courtesy of Drawn and Quarterly’s translations of the complete run of the Moomin comic strip and several Moomin storybooks (including Who Will Comfort Toffle? [1960]).

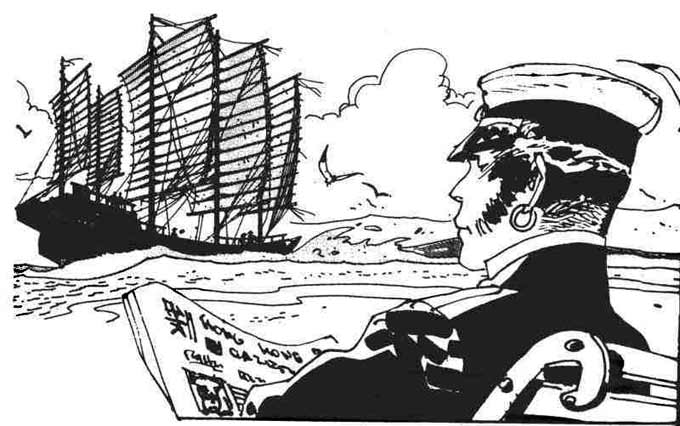

In the case of Corto Maltese, the influence runs in the opposite direction, from America to Europe. Inspired by comic-strip dramatists Noel Sickles (Scorchy Smith) and Milton Caniff (Terry and the Pirates, Steve Canyon), Italian artist Hugo Pratt developed his own realistic style, and his own adventure character, freebooter Corto Maltese. Of all the works in the “Classics” category, Corto Maltese is the hardest to find in English — virtually all the Corto volumes published in America by NBM and others are out of print — but the inky beauty of Pratt’s images is a universal language.

The Revolutionaries: Blueberry by Jean-Michel Charlier and Jean “Moebius” Giraud (1965- ); Alack Sinner by Carlos Sampayo and José Munoz (1975-1988); Arzach by Jean “Moebius” Giraud (1975-76); The Hermetic Garage by Jean “Moebius” Giraud (1976-78); Fires by Lorenzo Mattotti (1986).

Like Corto Maltese, Blueberry and Alack Sinner are European reflections of American genres. Blueberry is Charlier and Giraud’s take on the Western, featuring Mike Blueberry, a cowboy and cavalryman increasingly trapped in post-Civil War political conspiracies, while Alack Sinner is a scarred noir detective who navigates the ideological hotspots (the Vietnam War, the feminist movement, Black Power) of Sampayo and Munoz’s own time. I call Blueberry and Alack Sinner “revolutionary,” however, because both deviate from and deconstruct genre through new techniques in art and storytelling; later Blueberry albums reflects the seismic changes in Giraud’s art when he adopts his “Moebius” persona (about which, more below), while the Alack Sinner story “Life Ain’t a Comic Strip, Baby” (translated in Fantagraphics’ Sinner #5, 1990) self-reflexively inserts Sampayo and Munoz into their fictional noir world.

It’s established comics lore how genre cartoonist Jean Giraud ingested hallucinogenic mushrooms, enthusiastically embraced the ‘60s counter-culture, and, under the pseudonym “Moebius,” wrote and drew the trail-blazing story “The Detour” (1973) for the relatively conventional French comics magazine Pilote. What followed was an explosion of creativity from Giraud — he co-founded perhaps the most influential comics magazine in history (Métal Hurlant [1974-2004], which off-shot into various languages, including America’s Heavy Metal [1977- ]) while continuing to explore unsettling, surreal territory in his Moebius-signed art. The four gorgeously-drawn, ferociously colorful, wordless stories that constitute the original Arzach cycle are named after a stone-faced pterodactyl rider who glides through a fantasy world with to its own subterranean cause-effect rules. Even trippier is The Hermetic Garage, which grew from a two-page throwaway in Métal Hurlant into a fully-formed science-fiction universe (and odd tribute to Giraud’s favorite authors, including Samuel Beckett and Michael Moorcock). Moebius’ comics sputter in and out of availability in English, which is a shame, though in the case of Arzach the language barrier isn’t a problem.

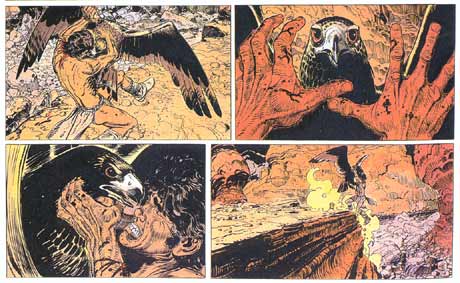

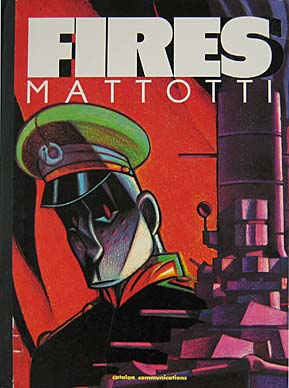

Lorenzo Mattotti’s Fires, perhaps the most radical of the “revolutionary” comics, combines Moebius’ subjective storytelling with the themes of Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness, as a naval officer struggles to understand his encounters with a tropical island culture. Most importantly, Mattotti’s painted images are so tactile and vibrant that critic Paul Gravett calls Mattotti “without doubt the most dazzling colourist working in comics today.” While I can point to numerous cartoonists influenced by Munoz and Moebius— Frank Miller is influenced by both — I’m hard-pressed to identify someone who’s followed Mattotti’s repudiation of ink line and explorations into solid blocks of color. Of all the entries on the Eurocomics list, Mattotti’s aesthetic is the closest to sui generis.

Lorenzo Mattotti’s Fires, perhaps the most radical of the “revolutionary” comics, combines Moebius’ subjective storytelling with the themes of Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness, as a naval officer struggles to understand his encounters with a tropical island culture. Most importantly, Mattotti’s painted images are so tactile and vibrant that critic Paul Gravett calls Mattotti “without doubt the most dazzling colourist working in comics today.” While I can point to numerous cartoonists influenced by Munoz and Moebius— Frank Miller is influenced by both — I’m hard-pressed to identify someone who’s followed Mattotti’s repudiation of ink line and explorations into solid blocks of color. Of all the entries on the Eurocomics list, Mattotti’s aesthetic is the closest to sui generis.

The Contemporaries: Epileptic by David B. (1996-2003) and Persepolis by Marjane Satrapi (2000-2003).

Both Epileptic and Persepolis were published by L’Association, the French art-comics publishing collective founded in 1990 by David B. and other prodigiously talented cartoonists (including J.-C. Menu, Lewis Trondheim and Patrice Killoffer). The excellence of the L’Asso backlist ensures the collective’s place in the canon, but other factors contributed to its popularity in the United States, most notably the translation and dissemination of key books via Chip Kidd and Pantheon’s graphic novel division, and Bart Beaty’s celebration of L’Asso in his “Eurocomics for Beginners” column in The Comics Journal and in his scholarly book Unpopular Culture: Transforming the European Comic Book in the 1990s (2007).

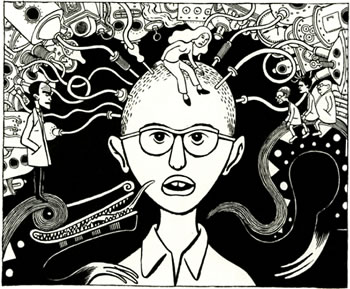

Epileptic is David B.’s searing chronicle of growing up in a family disrupted by a brother with severe epilepsy and depression; the scenes where B(eauchard)’s parents turn to macrobiotic diets and communal living to “cure” his brother’s disabilities are among the most harrowing and truthful I’ve ever read in an autobiographical comic. Paradoxically but effectively, David B. opts to depict his life in Expressionist visuals, depicting his brother’s epilepsy as fluid demonic patterns, and self-help gurus as looming, out-of-proportion golems. Marjane Satrapi adopts some of B.’s strategies—autobiography rendered in stark black-and-white graphics—but she has her own story to tell, about her childhood and young adulthood in post-Islamic Revolution Iran. 9/11 and the rise of Jihad vs. McWorld tensions turned Persepolis into a transatlantic bestseller.

I expect this list of canonical Eurocomics to expand considerably in the coming years. If we repeat this exercise in ten years (as the British Film Institute does with their “Top Ten Poll”), I’m sure that the effects of Fantagraphics’ Jacques Tardi reprint project will place a book like Tardi’s It Was the War of the Trenches (1993) on the list. (Actually, I’m surprised that Trenches didn’t make it this time.) And maybe in a decade new translation projects — A Blake and Mortimer collection? An anthology of Italian underground comics from magazines like Cannibale and Frigidaire? — will lead to a revised Eurocomics canon, though it’s hard to imagine the dethroning of Tintin. But who knows? We didn’t expect the fall of the Berlin Wall either.