As any reader of Alan Moore’s Swamp Thing can tell you, there’s little doubt that the emotional core of the series is Abigail Arcane Cable, initially Swampy’s friend, later his paramour, and still later, his common-law wife. Moore’s greatest coup in the series was in turning Abby into what is probably the greatest female character in the history of mainstream superhero comics. Admittedly, the competition isn’t much to write home about, but Abby (and Moore) clear the bar with room to spare. It’s easy to forget that Abby was initially the Bavarian niece of a mad scientist who wanted to steal Swampy’s body for the purposes of immortality (yes, that hoary old trope). For this reason, Abby could easily have been repurposed as “traumatized in youth,” as “stranger in a strange land,” or even as “exotic sexual object” without necessarily betraying her history. Moore does none of the above. Despite being faced with a variety of horrors (demons, monsters, monkey kings, werewolves, super-powered alcoholic husbands possessed by the spirit of her insane uncle), Abby is never reduced to a “damsel in distress” that the hero rescues in episode after episode, nor is she (like the typical female superhero) depicted as a balloon-breasted, spandex-clinging object for the male reader’s masturbatory viewing pleasure. Instead, Abby is a smart, brave, resourceful woman who is more interested in helping others than in “being saved,” and whose beauty and sexuality are only a part of her intellectual and emotional arsenal. She also usually wears jeans.

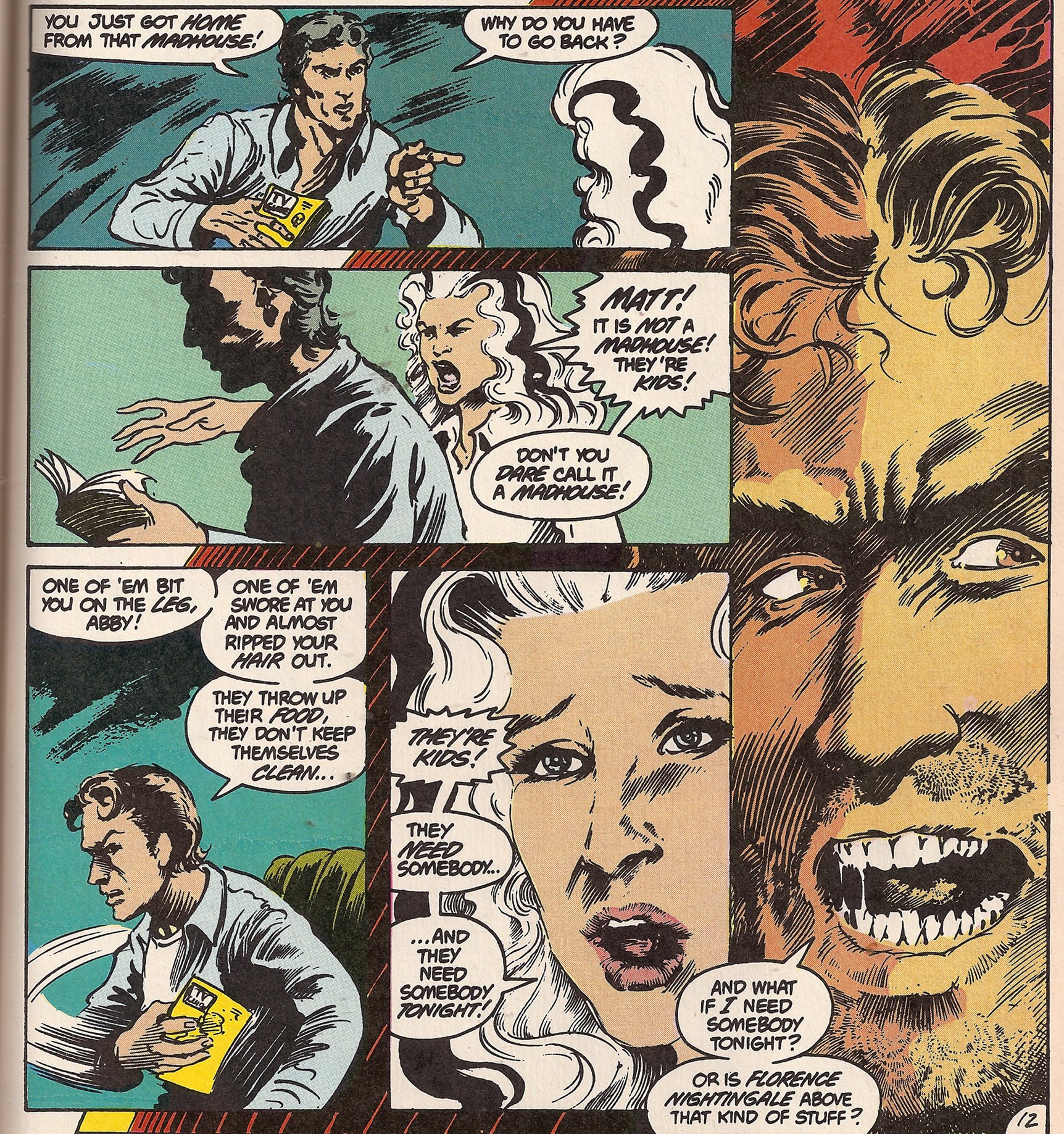

Abby does her share of screaming and running (more the latter) in the early episodes and is “rescued from hell” in Swamp Thing Annual #2 (the template for Sandman and a variety of other Vertigo series). However, from the very beginning it is clear that she is never present just to be rescued. In issue #26, Abby identifies a monstrous threat to Elysium Lawns, the home for autistic children at which she works, and heads off to help because “they need somebody tonight.” Her husband’s leering reply and her scorn for it, indicate early on that Abby is not to be seen as mere object for the male gaze.

Instead, this scene makes her the “hero” of the episode, even if she must finally bring Swampy, Etrigan the Demon, and Paul, the autistic child, into play in order to conquer the threat. The story itself is pretty stupid, bringing out the worst of horror clichés (“I will show you your deepest fears!”) and ends with a whimper, not a bang. Abby’s role, however, sets the stage for her importance to the rest of the series, and Moore’s commitment to woman characters who aren’t just window-dressing.

As previous posters have mentioned, not all of Moore’s attempts at feminism “work,” with the werewolf issue (#40) being a particularly egregious example of overwriting and overmoralizing. The depiction of a woman confined, domesticated, and objectified by male society (and who wreaks her revenge by transforming into a werewolf at “that time of month”) strains even the most good-hearted of liberal sympathies. The inevitable suicide by the werewolf doesn’t help either, following as it does, a string of literary/cultural representations that suggest that the best way “out” of a patriarchal society is not social change, or even a display of female strength, but a resignation in death. “The Curse” is definitively not as well written as novels like Virginia Woolf’s “The Voyage Out” (not quite a suicide, but close enough) or Kate Chopin’s “The Awakening,” and its conclusive “message,” coming from a bunch of men producing a superhero comic, is even more disheartening. As someone in the letters column noted, even the medium of self-inflicted death is irredeemably dumb, since no grocery store would be idiotic enough to display its sharp knives with the points facing out (would they).

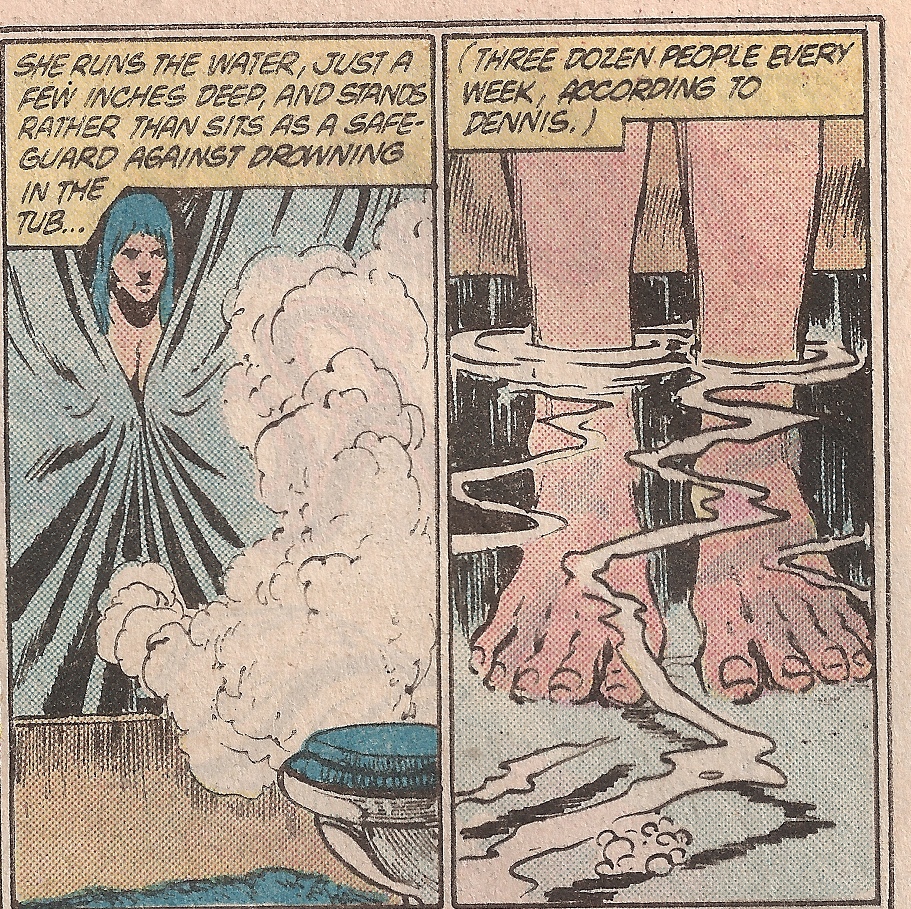

Still, Moore is nothing if not willing to correct his mistakes (or to return to his favorite themes), and his return to explicitly feminist motifs in issue #54 is one of my favorites. In “The Flowers of Romance,” marginal characters Liz Tremayne and Dennis Barclay return after a three year absence in the issues following Swampy’s “death.” Liz and Dennis were friends of the Cables in the Marty Pasko run on the series, and in the time since readers last saw them, Dennis has used their supposed pursuit by the Sunderland Corporation to make Liz, a previously dynamic and professional woman, completely dependent upon him. If there’s any horror in this series, it’s in this story. With Swamp Thing dead and no monsters or demons in sight, the issue depicts Liz’s psychological rape. Dennis convinces Liz not to use electronic equipment for fear of electrocution, to wear towels as underwear, to stand up in the bathtub for fear of drowning, etc.

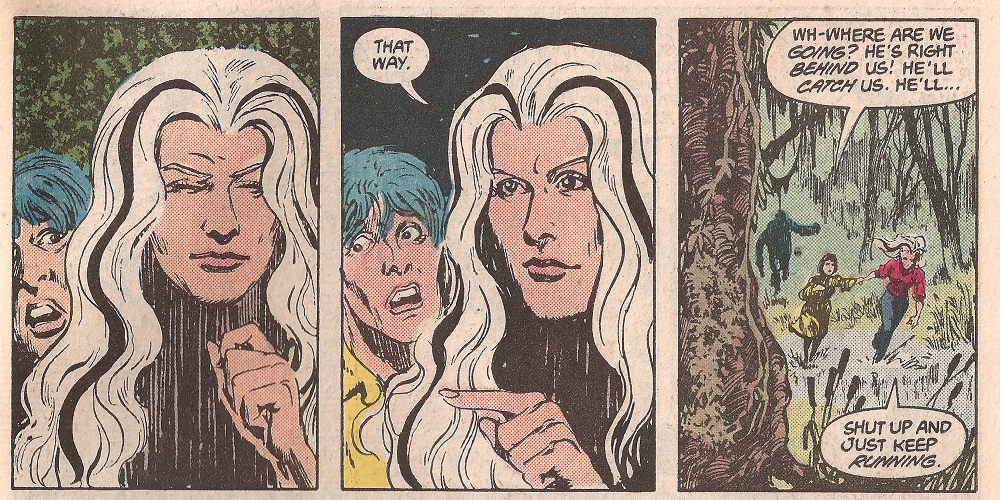

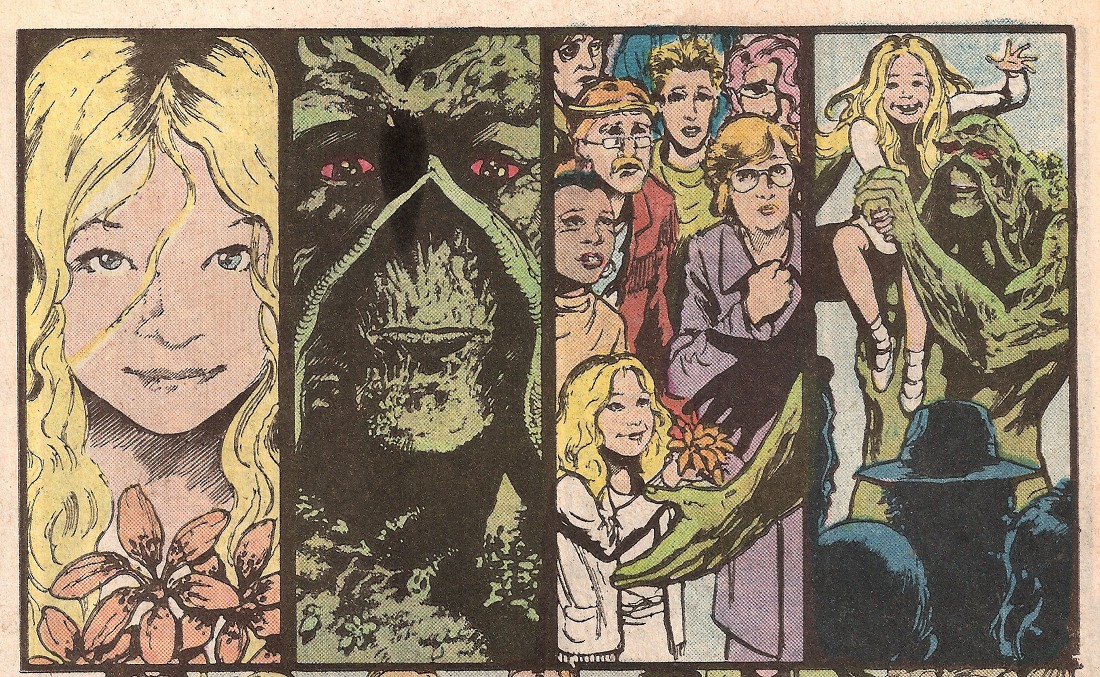

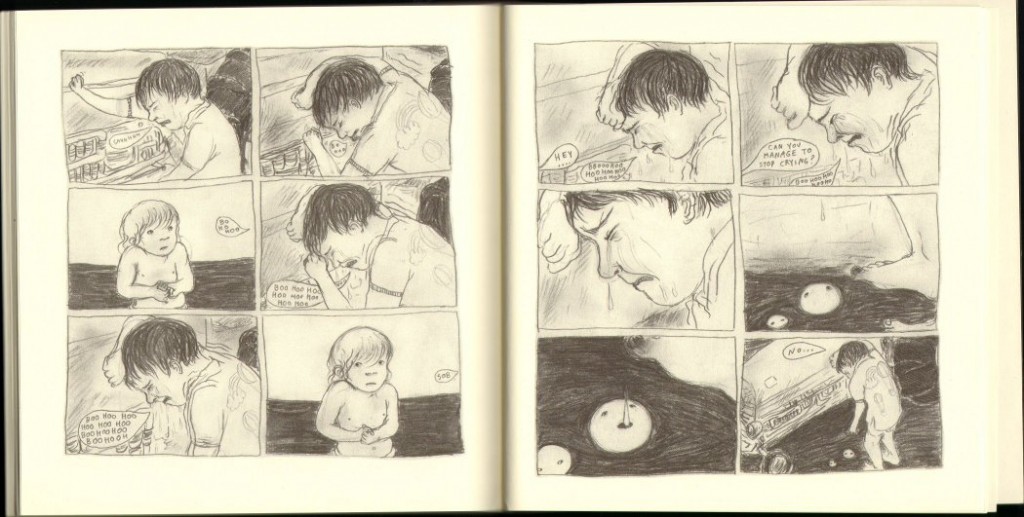

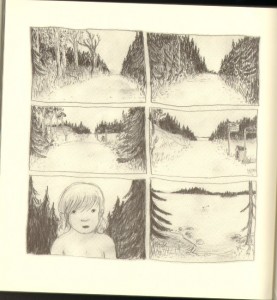

Fear is used as manipulation in the story as it is by Norsefire in V for Vendetta in order to establish the fascist state. Here, though, the fear is personal and the depiction of an abusive relationship is harrowing long before Dennis even makes his appearance in the story. In this case, the gendered political message arises out of a single relationship, affirming the feminist mantra that “the personal is political.” Like the men of “The Curse,” Dennis mentally cripples, domesticates, and imprisons a woman—but here the theme feels less like a hectoring prose-poem and more like an adventure story with cunning insight into personal psychology and social practice. Here also, the woman is saved not by resignation, but by individual agency (when she finds the courage to turn on the television and to leave Dennis to find Abby) and by another woman: Abby. Abby, herself traumatized by Swampy’s death (depicted beautifully in a pair of wordless pages) takes Liz in and protects her from Dennis, who follows her in an attempt to bring her back under his control, or wreak revenge. Dennis is armed and clearly insane, but Abby keeps her head and manages to lure him into the swamps, where he is ultimately consumed by alligators.

The result is, without a doubt, and with some degree of cliché, female “empowerment,” as Liz begins a slow ascent back to her previous self (mostly accomplished in Rick Veitch’s run on the series), and Abby begins to move on with her life.

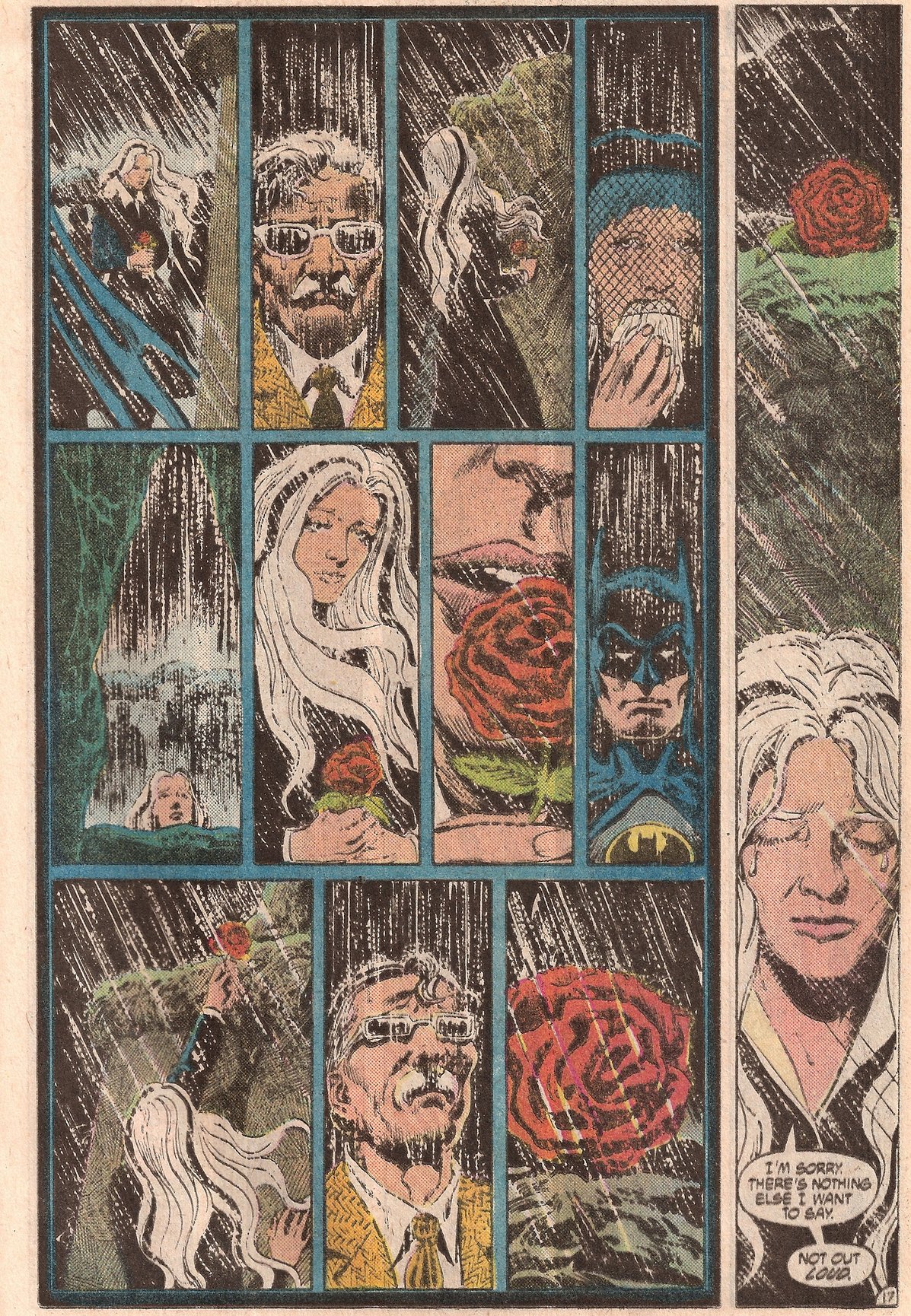

Abby’s resiliency, combined with the focus on the strength of the female community in resisting masculine power, reminds the reader that Abby cannot merely be defined as “Swamp Thing’s girlfriend.” Rather, her identity exceeds that role and has the capacity to redefine itself. Since everyone involved (reader, writer, artist) knows very well that Swamp Thing will return, Moore certainly had the option of having Abby wallow in misery for the requisite number of issues until the hero’s return. The fact that she begins to “bounce back” only a month after Swampy’s death suggests that Abby may, in fact, be the hero of the book, the personality around whom Swampy revolves, rather than the reverse. Another high point is in the following month’s episode, devoted to Swampy’s funeral in Gotham. Batman invites Abby to make a public statement, perhaps even to “condemn us for our lack of understanding,” but Abby’s impulse is to keep her private love private, not to flex her muscles, or her “rights,” but to mourn in her own way.

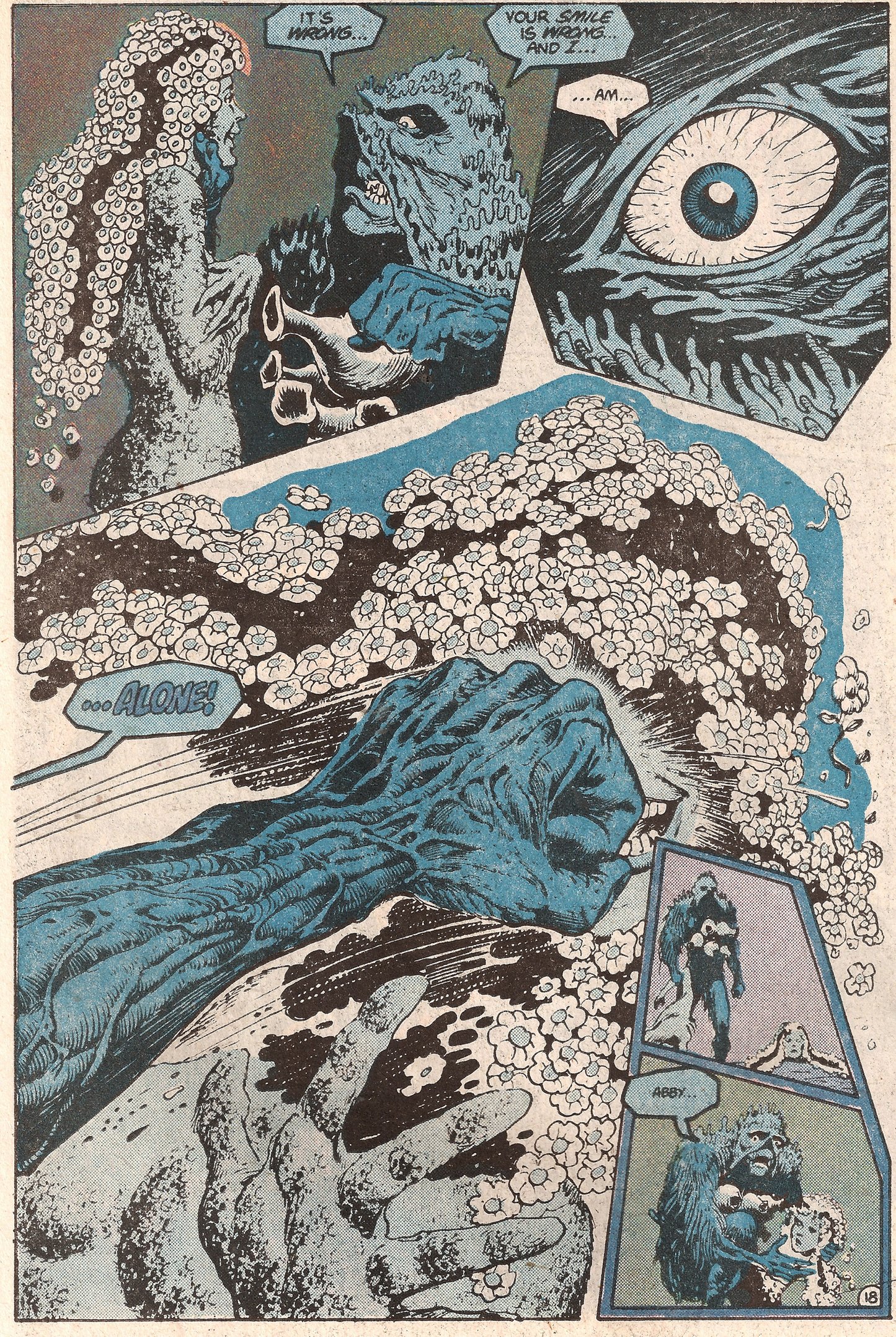

After Swampy’s very public, and ultimately futile expression of his own feelings, Abby’s quiet moment of mourning presents a stark contrast, and a display of inner strength (if not of public power) that exceeds Swampy’s. In the first month of their separation, Swampy comes much closer to madness and “giving up” than Abby herself ever does, going so far as to create a “vegetable Abby” (and an entire hallucinatory supporting world) in order to cope with his loss (in issue #56).

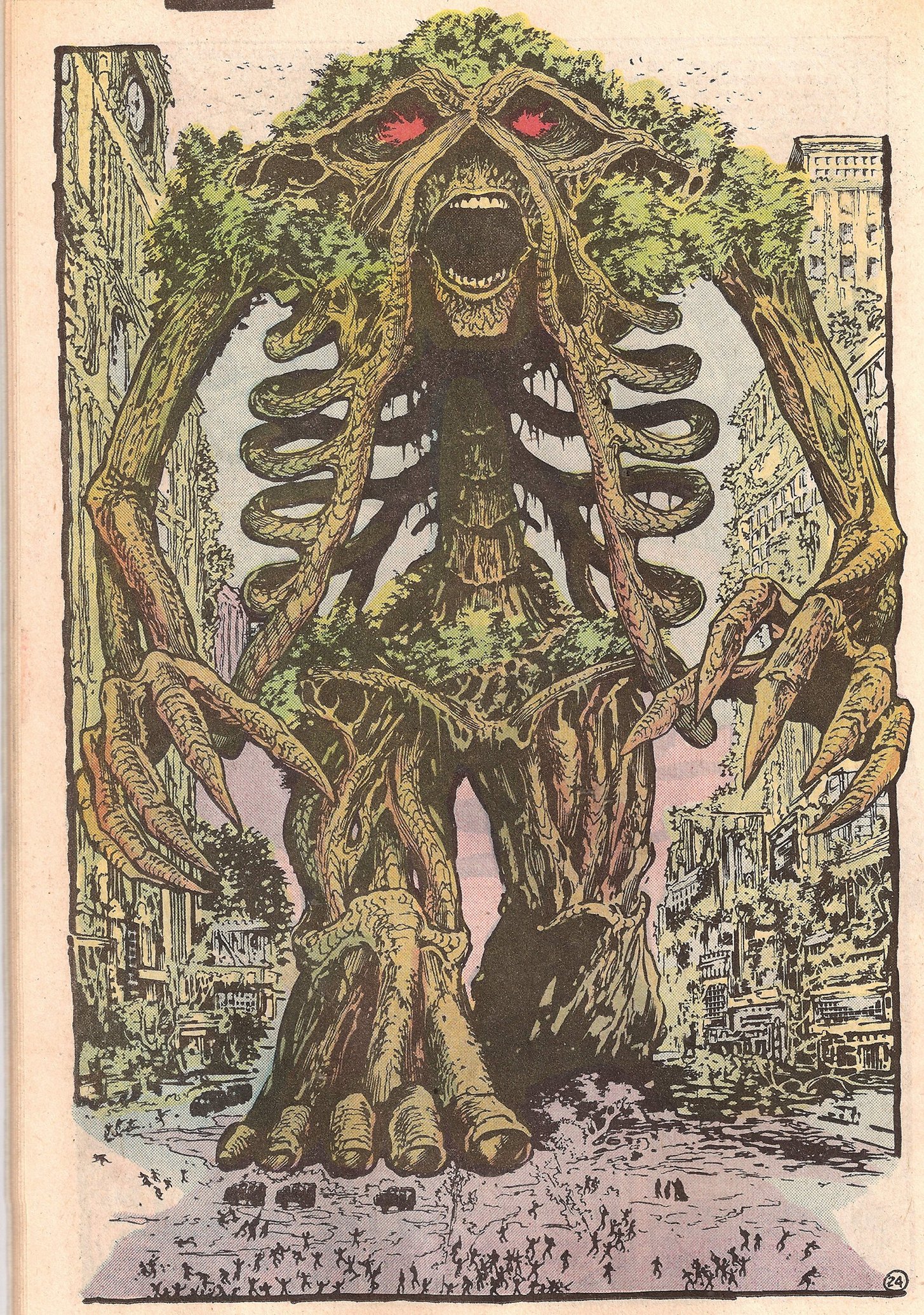

Abby’s centrality and resiliency is never meant to minimize the intensity of the connection between the two characters. It does, however, begin to put Swampy’s own “heroic” status into question. The entire final year of the series gets its power, immediacy, and impact from the love between Abby and Swampy, but that very relationship begins to take on some troubling ambivalence. “Outed” in the tabloid press as being a vegetable-lover, Abby is arrested and brought to Gotham City, providing the set-piece for one of the coolest “battles,” and the finest art, in Moore’s run. John Totleben’s solo effort in the double-sized #53 is the piece de résistance of Swamp Thing illustration and of Moore’s overactive imagination. Popping out ideas for Swamp Thing’s vegetable powers faster and with more frequency than a nuclear-fueled pez dispenser, Moore reveals Swampy’s power to flood the air with aphrodisiacs and hallucinogens, to grow in the human intestinal tract, to occupy multiple bodies simultaneously (not safe for Batman), and to become a huge redwood Swamp Thing, thanks to the Gotham botanical garden.

All of these “tricks” are exercised in the pursuit of Abby’s peaceful return, linking the most “public” and superheroic of the series’ moments to its most personal. The series is at its worst when pitting cosmic evil vs. cosmic good (as in the similarly double-sized issue #50), but it is at its best when focusing on the most personal emotions. Swamp Thing #53 is about that most banal of story ideas, “the power of love,” but that idea is exhibited in startling (and troubling) new ways, when an entire city is transformed into a jungle and redwood-Swampy towers over it. Moore’s typical critique of and aversion to “power” is here put under pressure by the celebration of love (and particularly love and sex unconstrained by social norms). In the end, though, the critique of power stands, and Swampy’s increasing (near omnipotent) strength ultimately undermines his love more than his love justifies the exhibition of that power. As in Watchmen and Miracleman, the exercise of power is not here a “good thing.” Instead, Moore warns (as he often does) of the tendency to mistake power for morality, to assert one’s personal beliefs/ideals in order to “save” others and, in so doing, to deprive them of freedom and agency. It is true, that Swampy fights against an arbitrary and unfair institutional power, but his efforts to overcome it materialize as a carbon copy of its faults, not as an alternative ideology. Swampy flexes his muscles and tries to show who has the bigger (redwood) dick, rather than proposing a communal compromise, or a mutually acceptable solution.

Swampy’s reveling in his newfound strength is punished, almost immediately, by the D.D.I. (some sort of shadowy government agency with a connection to the remains of the Sunderland Corporation) and Lex Luthor, but it is initially difficult for the reader not to sympathize with him, since his display seems connected to the hippy values the series evinces elsewhere, even in the same issue. Even as Swampy asserts his own personal needs over and against the community of Gotham, that community seems to respond powerfully and positively, with Gotham’s dormant “flower-children” embracing Swampy and his values of “love,” “nature,” and “community.”

Since these values are also the series’ (and represented most iconically by the Abby/Alec connection), it’s a tough pill to swallow when Swampy is killed/banished at the moment of reunification.

It is equally troubling, if for opposite reasons, when the couple’s second reunion (Swampy’s return to Earth in #63) is delayed by a series of “revenge murders” of the DDI operatives on Swampy’s part. In “Loose Ends (Reprise),” even the title indicates that Swampy is repeating the atrocities committed by DDI/Sunderland, not escaping them. Back in Moore’s first issue, entitled “Loose Ends,” Sunderland cleaned up the titular hanging threads of Marty Pasko’s run on the series by pursuing and killing Swampy and his friends. Now, with power on his side, Swampy does the same to the DDI operatives. The series spends its final year exploring and emphasizing the importance of the (stereotypically feminine) values of love and community at the expense of the (stereotypically masculine) values of power and violence, but it is a lesson that Swampy himself doesn’t seem to learn. His first move on his return to Earth is another ostentatious display of power, similar to the one that got him “killed” in the first place. Mowing through the DDI/Sunderland killers before he even lets Abby know of his return, he places power/violence chronologically and ideologically before love, even as Abby is drawing strength from her newfound community of friends and associates (Liz Tremayne, Chester “tuber head” Williams, etc.)

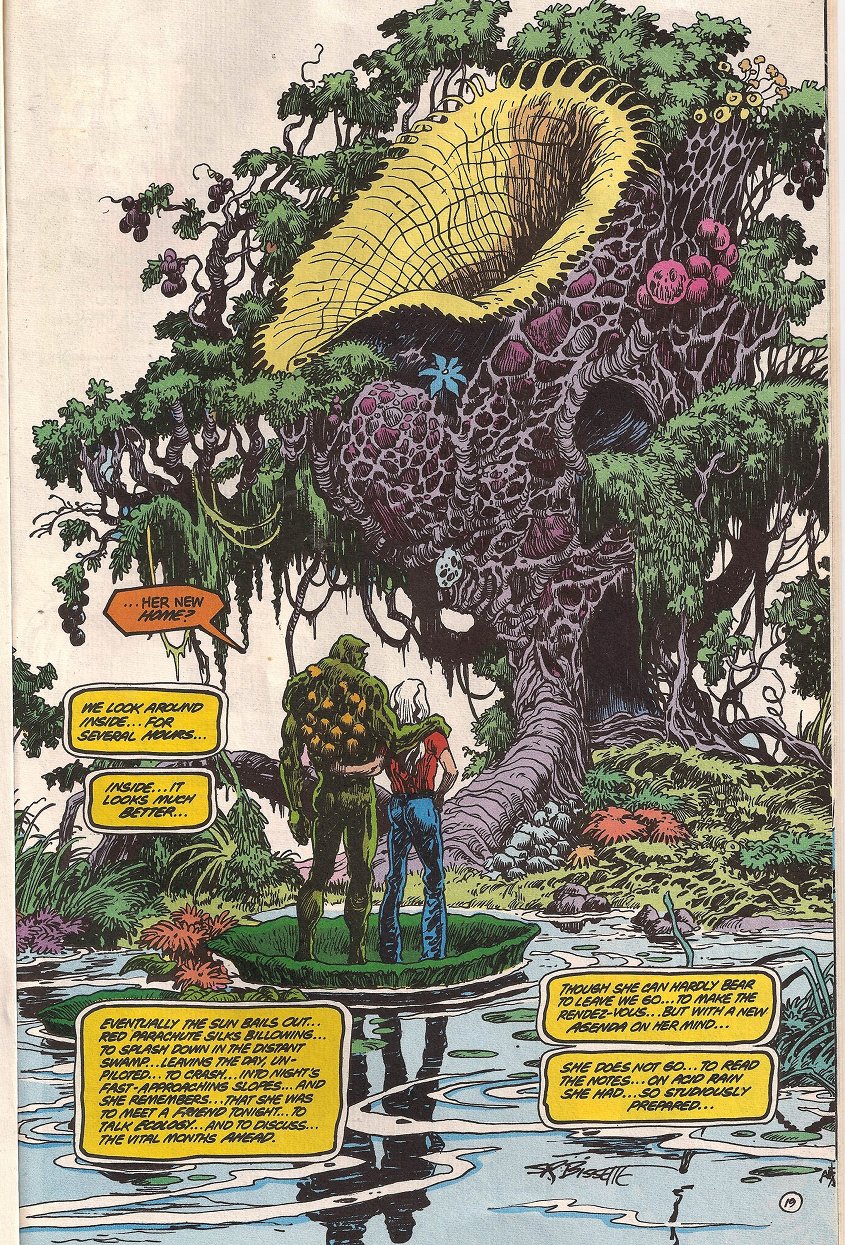

Moore’s run on the series soon concludes with a “domestic paradise” with Swampy withdrawing from the world and constructing a “lime tree bower” for his lady love. Still, on re-browsing (and re-thinking) it is questionable whether or not his return is to her benefit. After all, Dennis Barclay constructed a “domestic paradise” for Liz, similarly enforced by his superior power and his professed love. Swampy’s heart seems to be in the right place in the final issue, but his means of getting there is on a pile of corpses. Given Moore’s critique of power elsewhere (even and especially supposedly benevolent power, like that displayed by Miracleman and Ozymandius), it seems unlikely that we are meant to view issue #64’s “domestic bliss” as a clear and pure “happy ending.” Swampy makes a vow to “withdraw” from human affairs, “to know and to never do”—for to assert his power, even for others’ benefit, would be to remove human agency and responsibility, as he finally acknowledges. Only one page after making this promise to himself, however, Swampy’s continuing hubris is evident. When Abby reminds Swampy that “they don’t build dream-homes” in the middle of the Swamp, Alec replies, “Perhaps they don’t…I did not intend to ask them,” constructing a “castle” for this muck-encrusted king and his consort. Swampy “does” without asking, without consulting anyone (including Abby herself). He continues to assert an almost incomprehensible power without considering the possible consequences. Swampy’s exercise of power hardly seems on the same level as the petty and repulsive brand applied by Dennis back in issue #54, but in the impulse to close Abby off from the broader world and to become her universe, he repeats Dennis’ basic ideology.

The happy ending is then plagued by the undercurrent of violence and power seen in the previous episode (and in the greening of Gotham). Thanks to the careful construction of Abby Cable over a period of almost four years, however, it is difficult to worry about her. She’ll take care of herself.

________

Update by Noah: You can read the entire Swamp Thing roundtable here.