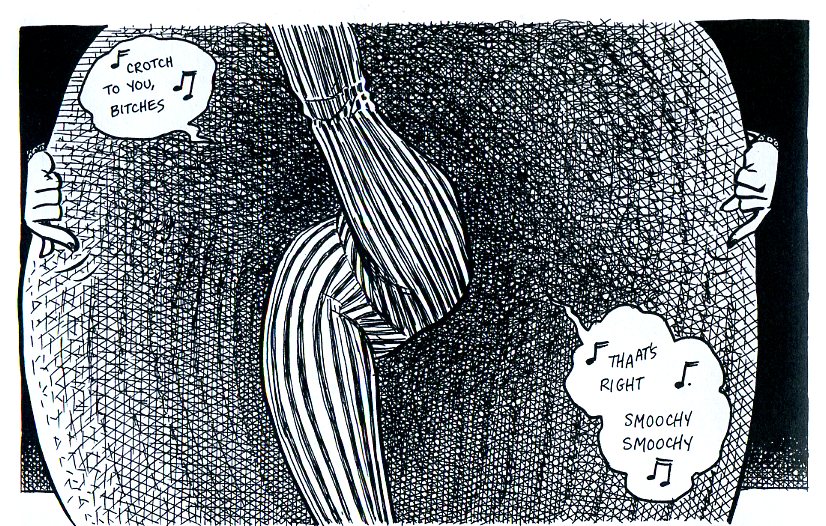

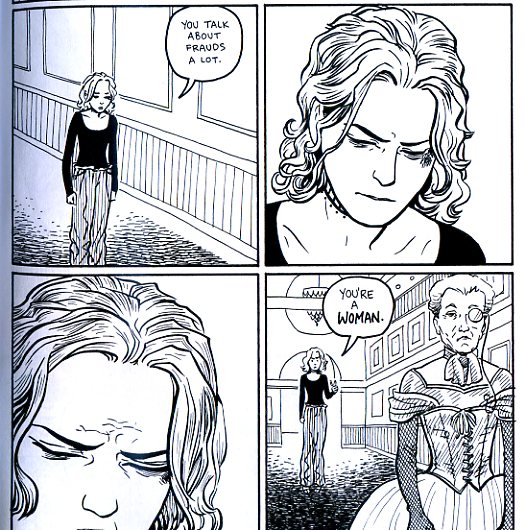

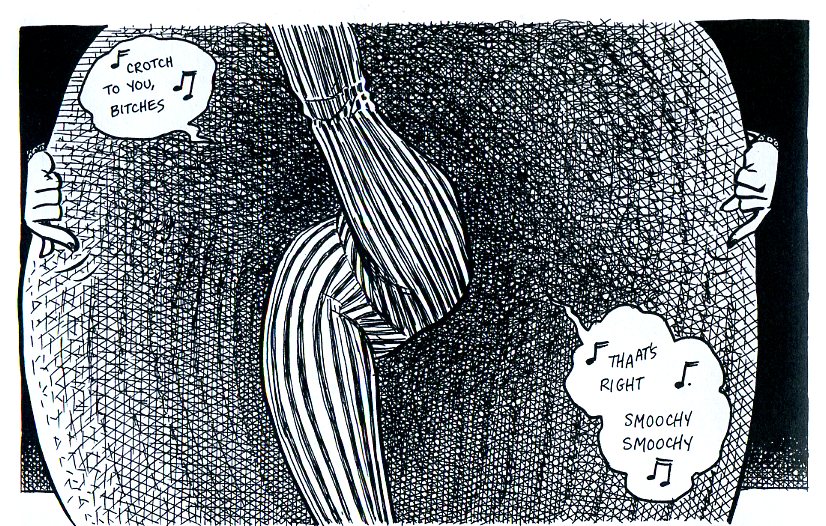

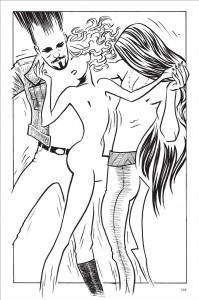

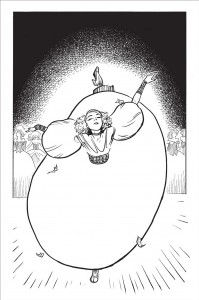

Carla Speed McNeil’s Finder:Voice starts with a beauty pageant — specifically, the Llaverac Clan Conformation Competition, as the text box/announcer tells us. The announcer goes on to explain that the girls are being judged to see if they fit the physical specifications of the Llaverac clan. The candidate being inspected (Jin St. John, we’re told) gets up close to the judges, thrusting her crotch in the face of one elderly woman, which is apparently in accord with contest traditions. Then, suddenly, a bulge appears in her panties. The elderly female judge recoils, and the announcer snickers, “I guess that’s why they call them ball gowns.”

Obviously, Jin has a penis — or, you know, maybe not quite so obviously. I read the first volume of Finder a while back, and so had at least a vague memory that Llavarec gender isn’t always quite what it looks like, but still, I have to admit that I was not at first exactly sure what I was looking at in those images above. McNeil does provide some additional clues in the next pages for the slow of mind…which, as one of the slow of mind who sort of but maybe not quite got the dick joke, I appreciated.

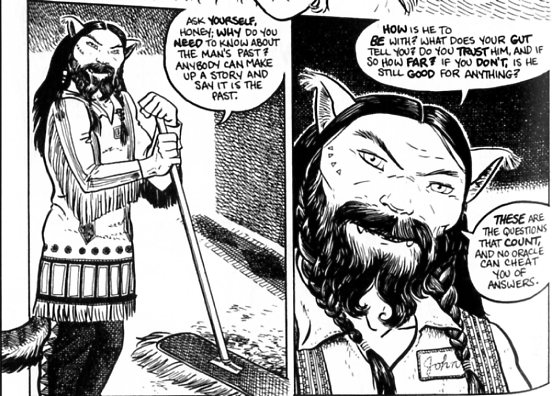

Again, my confusion around the dick is a sign that I’m a little dense. But it’s also, I think, thematized by the comic. The Finder series is broadly cyberpunk, and one of the characteristics of cyberpunk is disorientation — a far future setting where social realities, and even physical characteristics, are so different from ours that it’s difficult to get your bearings. McNeil provides some notes at the back which help a bit…but even those end up often emphasizing the extent to which the world on view here is a mystery. “Can’t remember for the life of me which clan the dude in the suite represents,” is a not atypical author’s note — suggesting that even McNeil herself is not the master of, but rather a bemused tourist within, the world she has created.

In Epistemology of the Closet, Eve Sedgwick argues that realist fiction is built around the manipulation of knowledge and lack of knowledge to create a kind of unspoken blackmail. The writer writes as if she knows everything in the world she has created, and the reader then pretends that she follows along, and knows everything as well. The reward for acquiescing to the author’s mastery is a sense of mastery for oneself — to acknowledge knowledge is to be the knower. There’s a complicity; a doubled pretense of knowingness.Sedgwick links this to the lines of force and knowledge around the closet, where what you know (i.e., who is gay) and what you don’t know (i.e., who is gay) become a matter of threat, mastery, power, and self-definition.

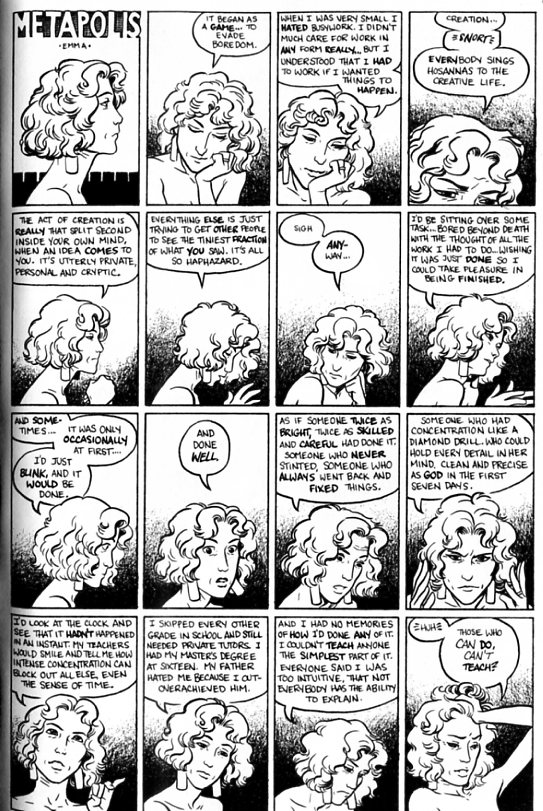

McNeil’s diffident stance towards her own work in her notes (emphasized again in a recent Facebook comment where she says ” I really had no idea what I was doing as a writer when I first began [Finder]”) seems like a rejection of Sedgwick’s formulation — a refusal of the pact of knowingness between writer and reader. And I think it is a rejection to some degree…though maybe, also, an investigation, or elaboration. Finder:Voice, in this reading, is deliberately about knowledge, about narrative, about the closet, and about the way people negotiate all those things, or try to.

The book’s protagonist, Rachel, is a Llaverac (and how do you pronounce that, anyway?) entered in the beauty pageant/conformation contest. Despite the fact that her father is not a Llaverac, she seems to be doing well, and seems like she has a chance to win, or at least make the cut to be accepted into Llaverac clan, with resulting honor, wealth, power, and the opportunity to share those things with her family. Before the final competition, though, she is robbed, and loses her hereditary clan ring — which means she’ll be disqualified unless she can get it back. The bulk of the story is devoted to her search for Jaegar, Rachel’s mother’s boyfriend, on whom Rachel has a longstanding crush, and who is an expert at finding lost items.

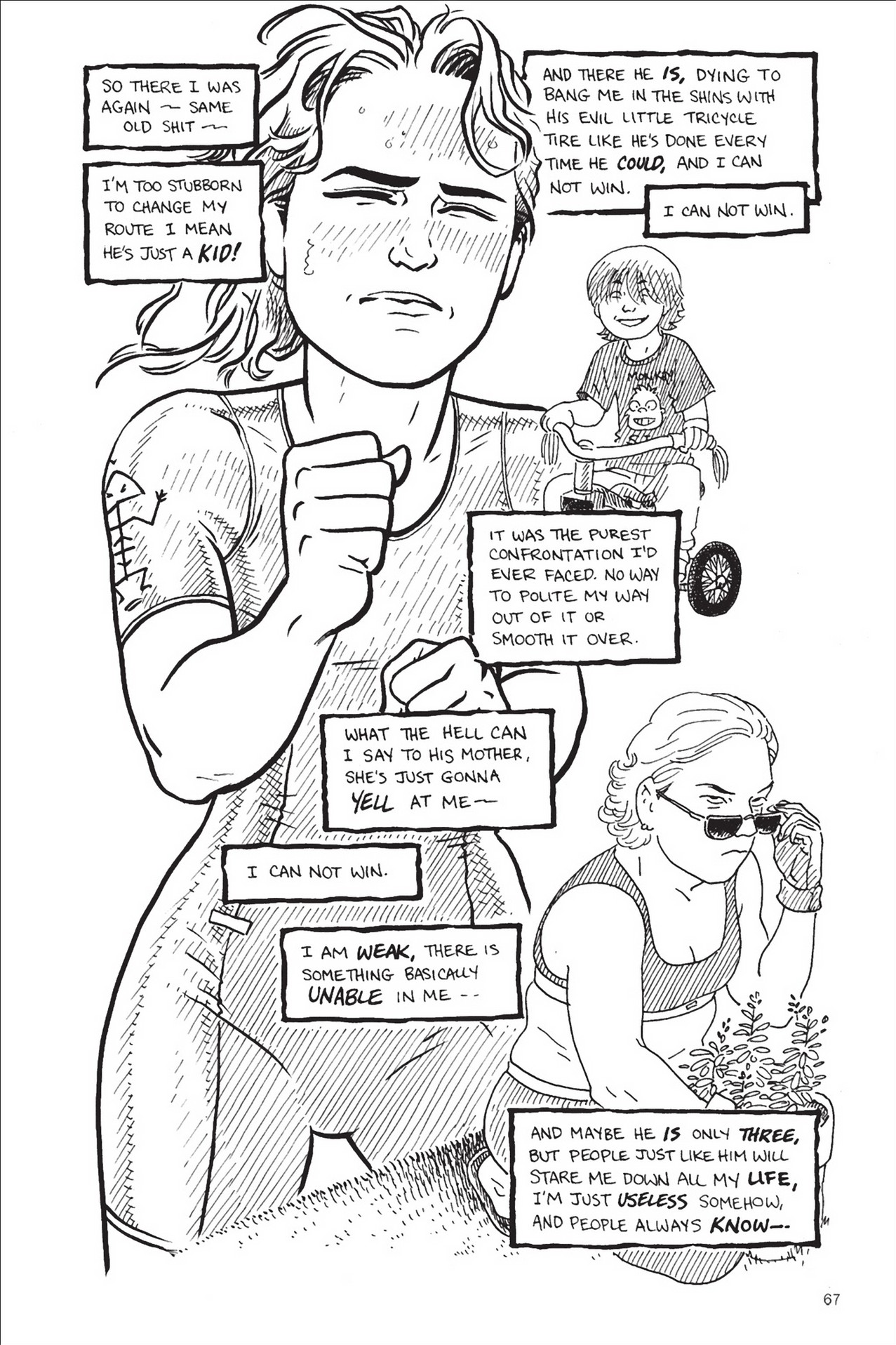

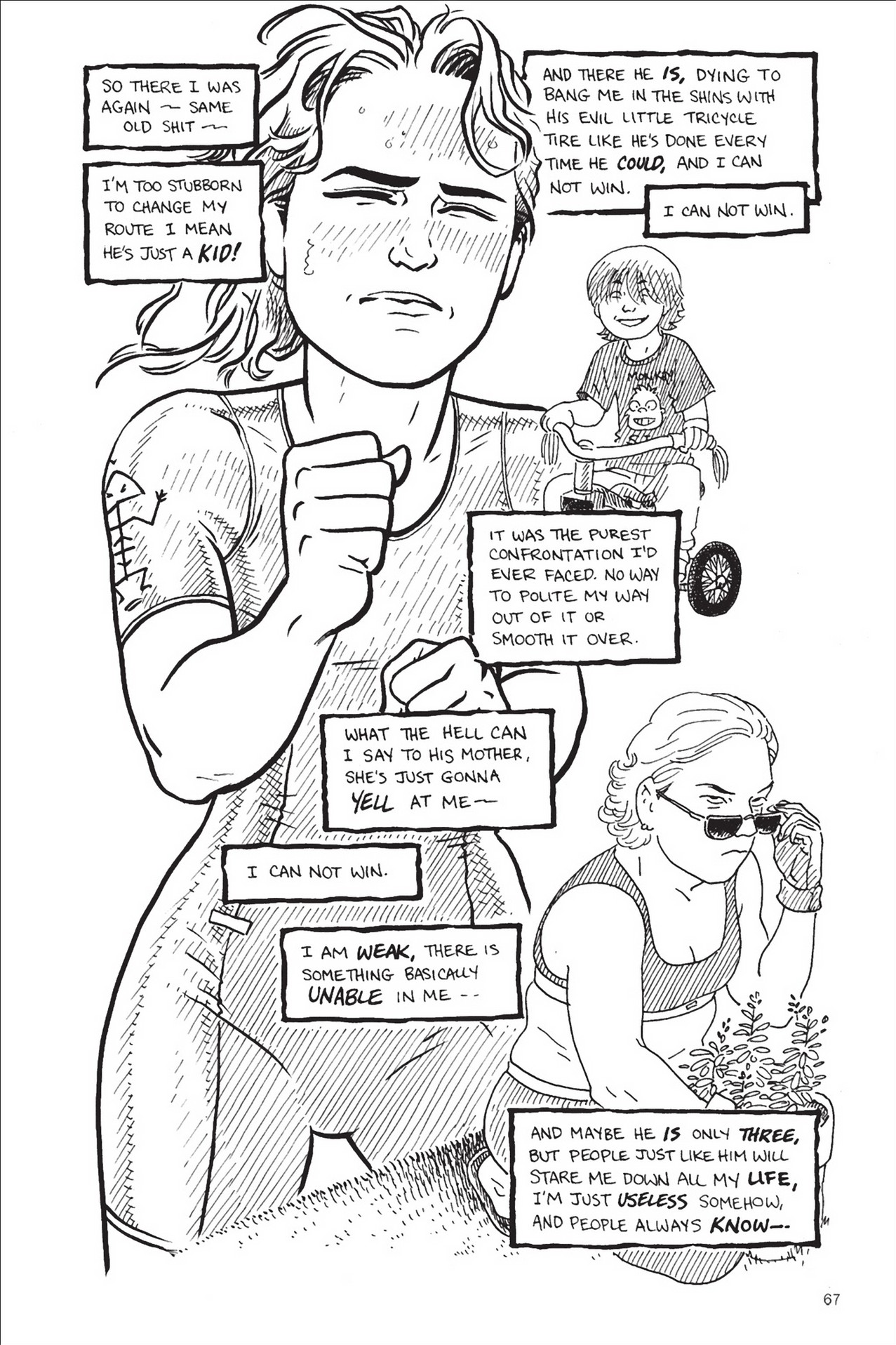

In his essay about Finder:Voice, Richard Cook points out that Jaeger functions in the Finder series in general as a hyperbolic lodestone of masculine competence and cool. The search for him, then, is in part a search for the penis or phallus. Rachel wants him in no small part because she wants to be him. She sees herself as incompetent; or as she puts it “I am weak, there is something basically unable in me.” Jaegar represents for Rachel not only her knight in shining armor, but her wish to become that knight. Part of her wants the ball gown — but part of wanting the ball gown is the hope that wearing it will mean she gets balls.

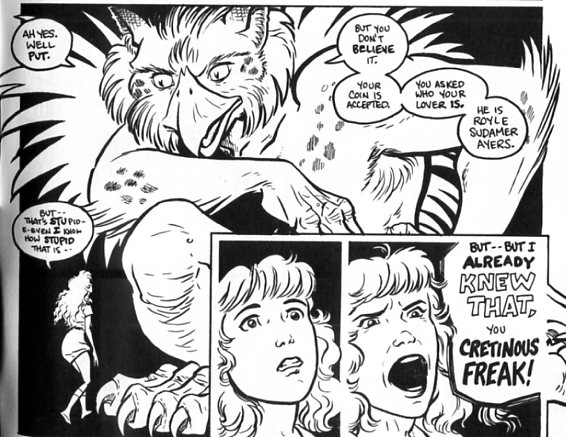

Wanting the phallus seems, at least, fairly uncomplicated — who doesn’t want power? And yet, the bulk of Voice is dedicated to demonstrating that balls are elusive, and that even when you find them it’s not always exactly clear what you have, or how to use it. In fact, you could almost see the book as a series of more or less false or confusing revelations about genitals. There’s Jin’s suddenly visible penis at the book’s beginning, of course. Then Rachel’s mom Emma tells her that her non-Llaverac dad is not her real dad; instead she’s the daughter of a Llaverac, Lord Rodzhina.

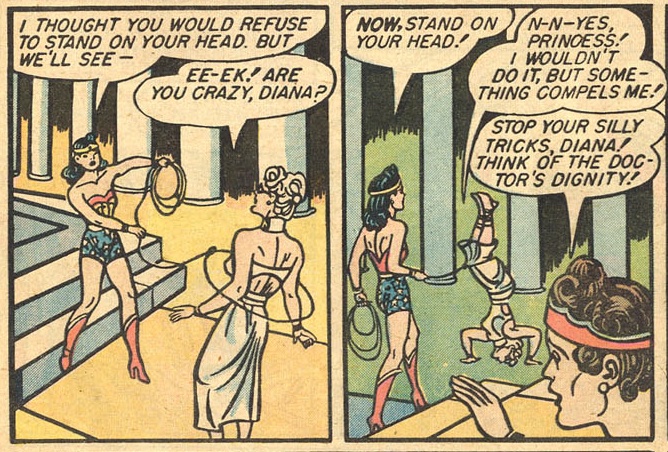

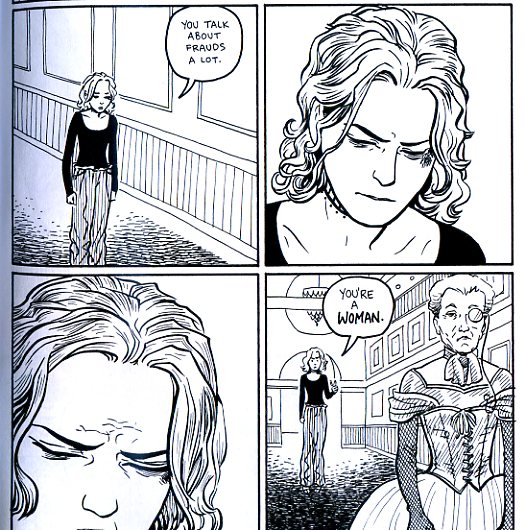

Rachel tries to get help from Rodzhina, but he refuses her because he thinks she’s incompetent (no balls.) Then, Rachel tries to get her sister Lynn to help her find the lost ring; when Lynne refuses, Rachel tells everyone who will listen that Lynn has a penis — only to have them laugh at her, because, yeah, they already knew that.

Finally at the end of the book, Rachel is allowed into the competition after she blackmails Rodzhina by threatening to reveal that he is not a man at all (which means, tangentially, that he is not her father.) He’s often helped get girls through the competition by claiming they were his illegitimate children — but he hasn’t actually fathered any children since he’s a woman, and having this made public would therefore cause him embarrassment and difficulties.

Rachel repeatedly fails, then, when she tries to manipulate knowledge about the penis. She only succeeds when she has knowledge about where the penis isn’t. This is mirrored in her search for the-penis-that-is-Jaegar; it’s only when she gives up on finding him that she manages to make progress.

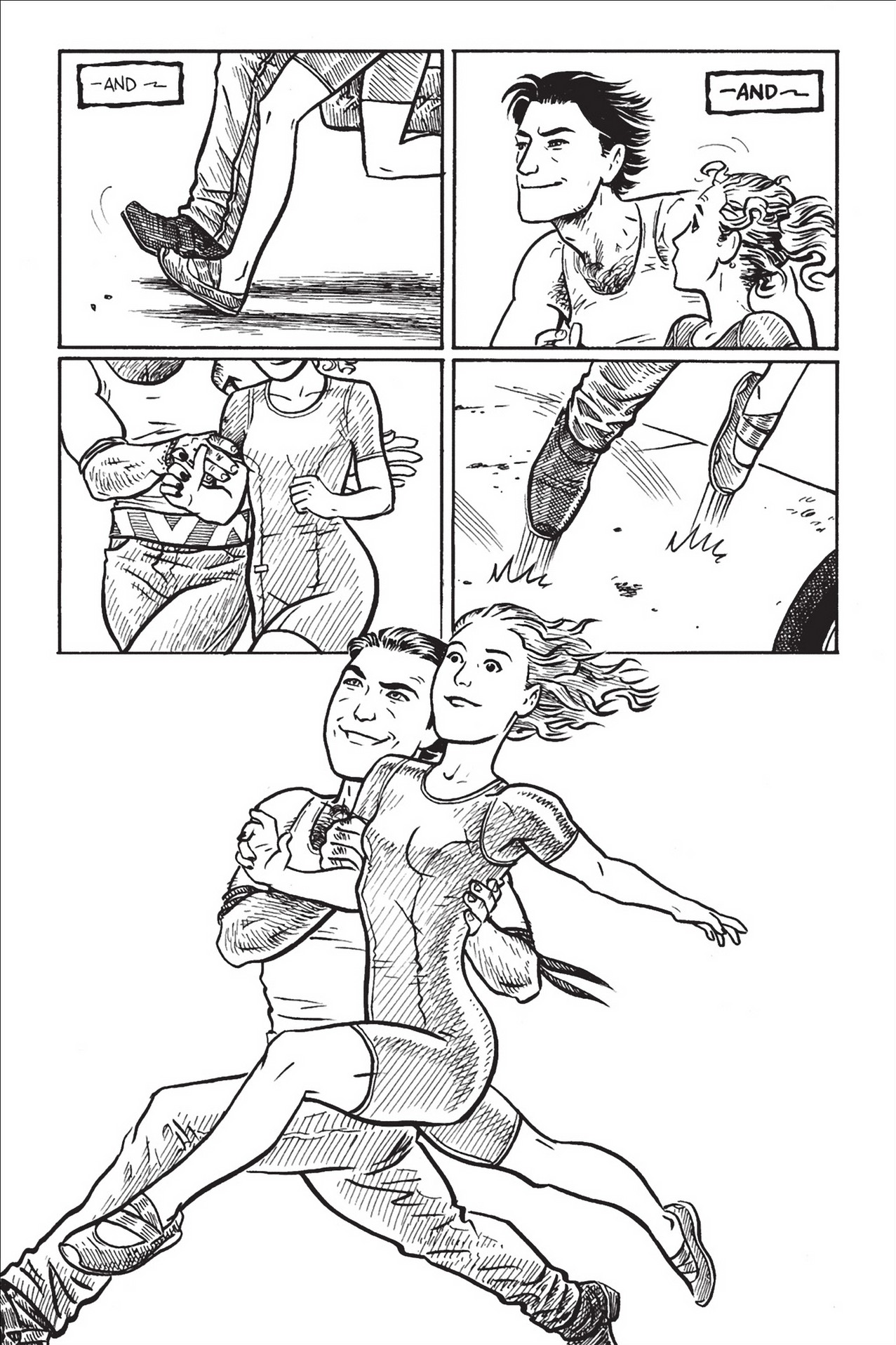

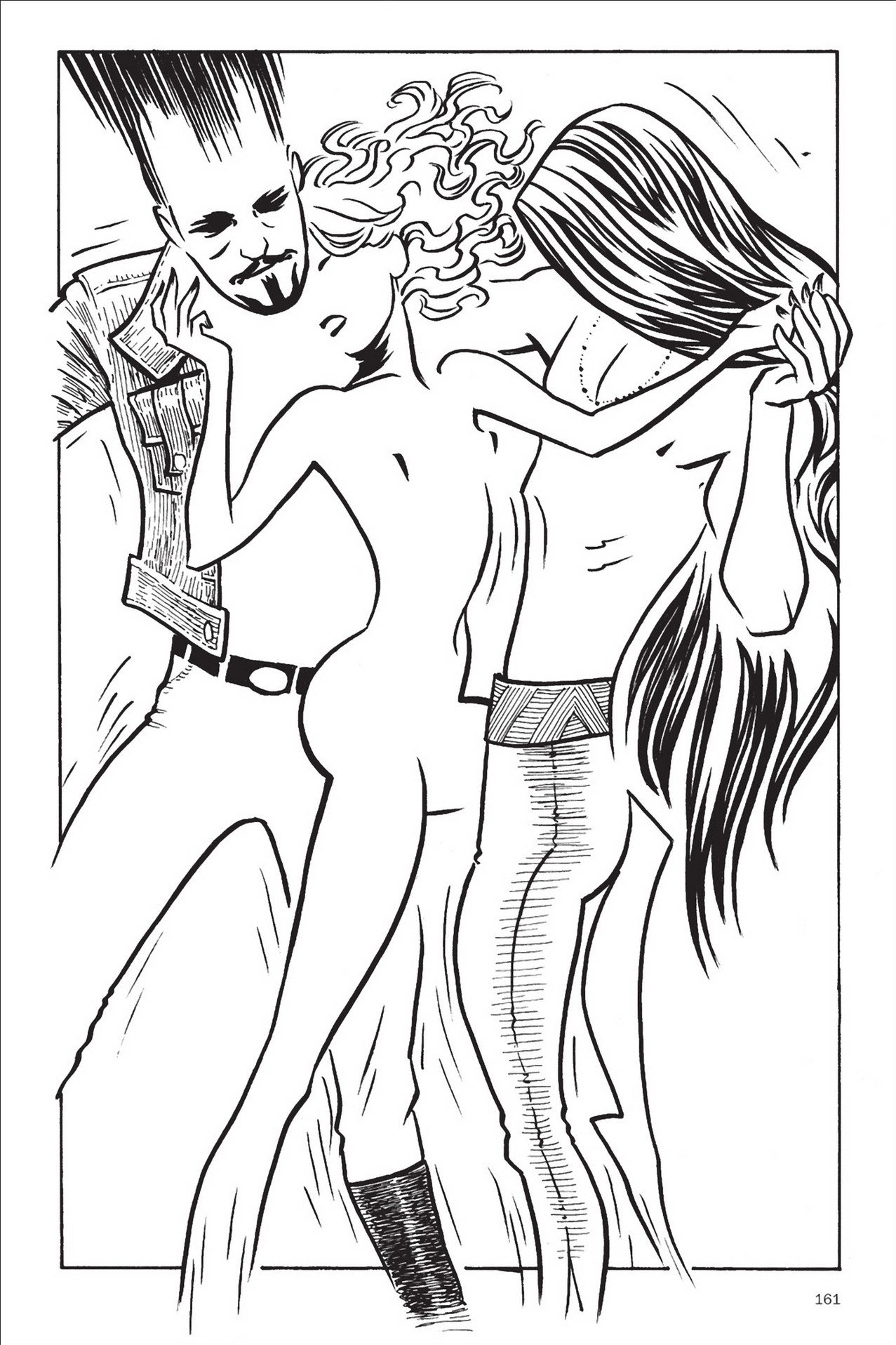

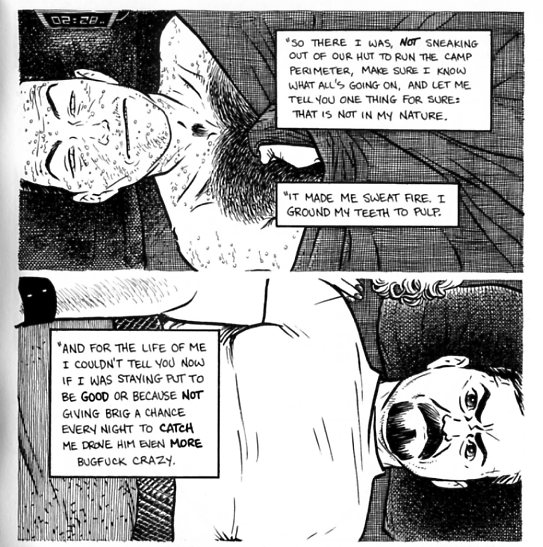

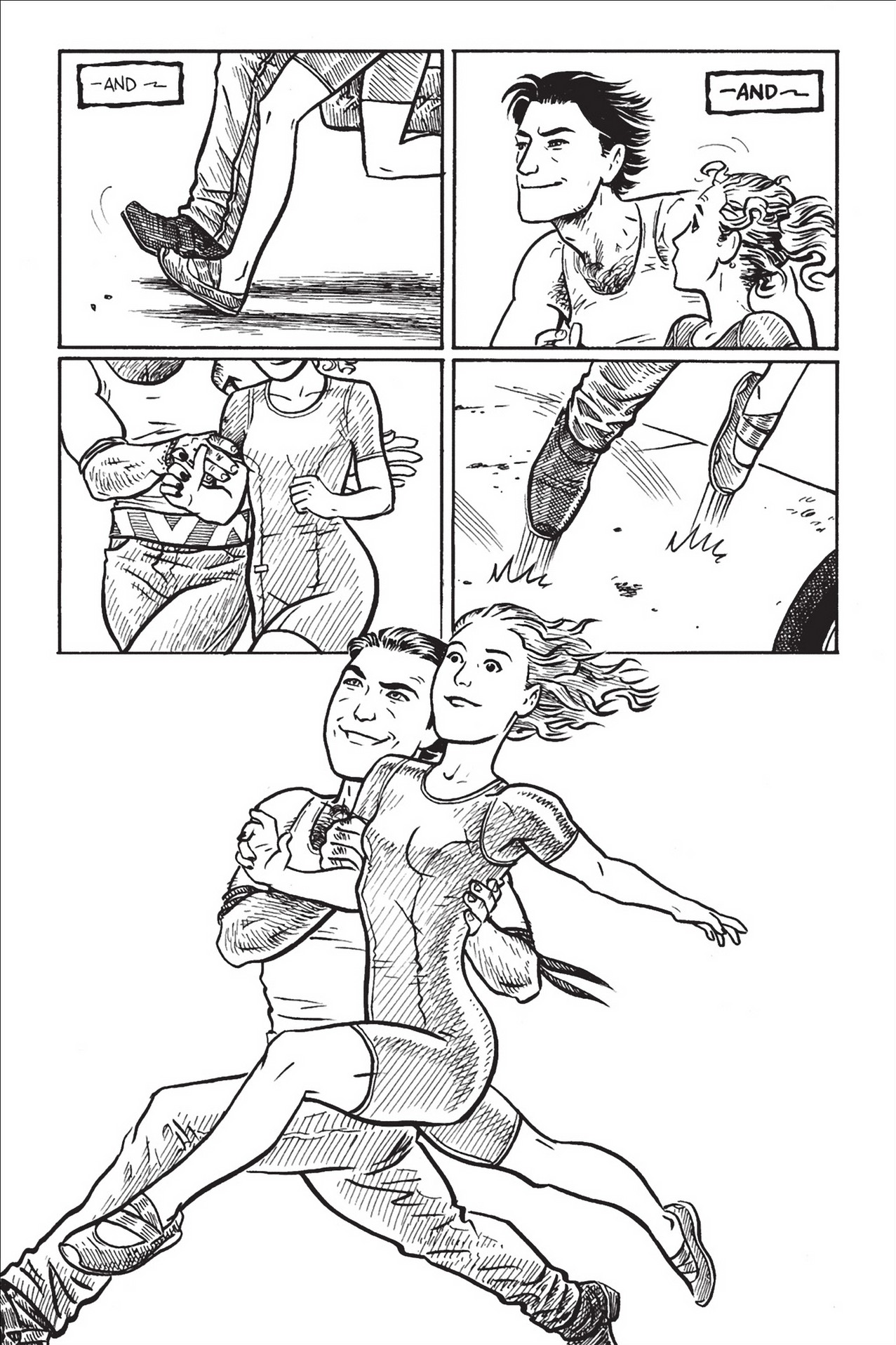

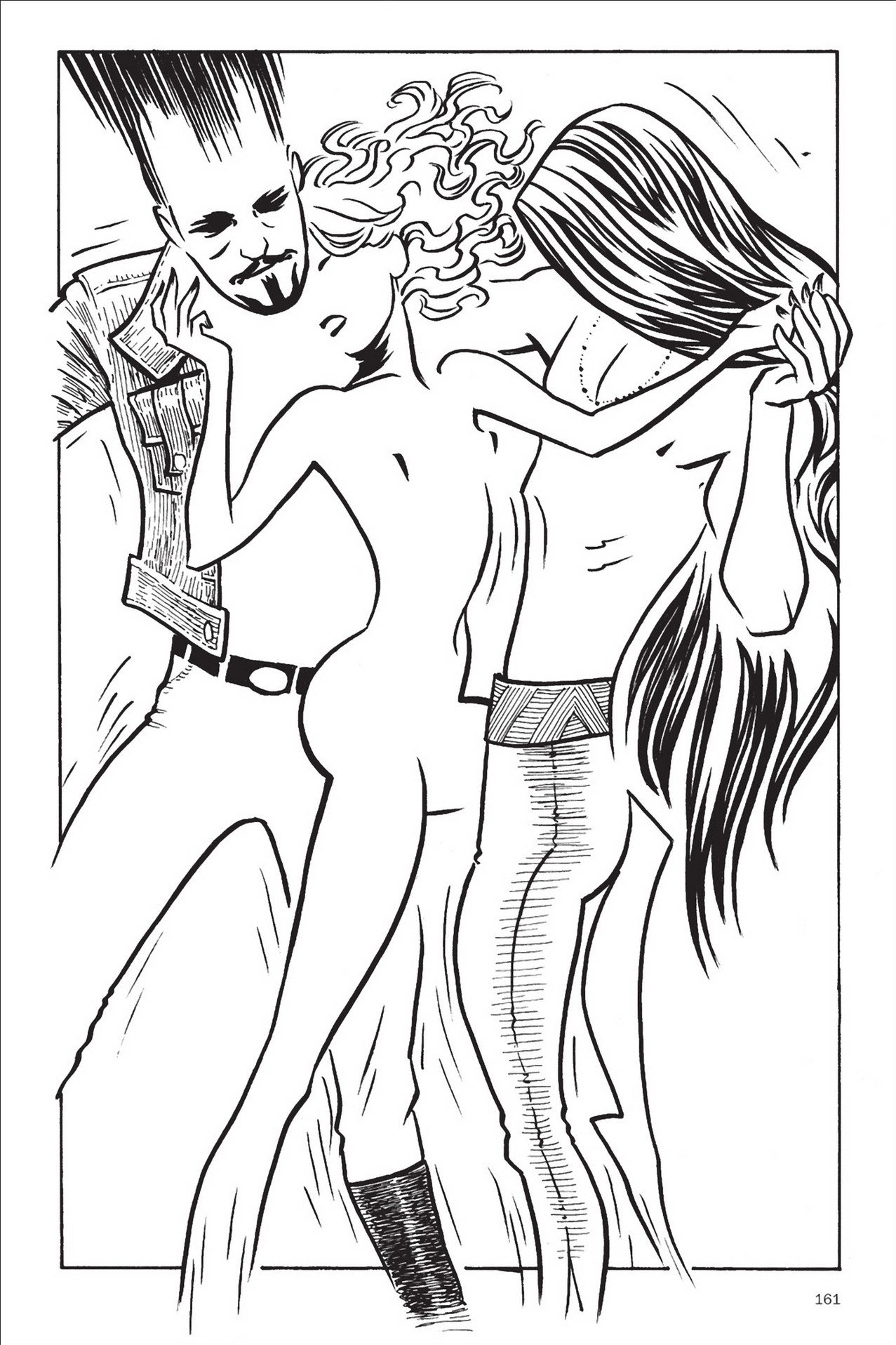

Said progress involves stumbling into a drunken orgy with a bunch of Ascians (a marginalized ethnic group, to which Jaegar belongs) and having them hand over an alternate ring — not hers, but someone else’s. She succeeds, then, by basically losing all knowledge of everything, even (especially?) her body — she blacks out, and doesn’t even seem to be entirely sure whether she had sex or not (at the end of the comic she’s wondering worriedly what she’ll do if she misses her next period.)

So…I don’t think Rachel’s choices are exactly supposed to be normative. This isn’t necessarily a celebration of zen and the art of being fucked senseless (and/or dickless). Rather, it seems like it’s a meditation on the way that gender and knowledge wrap around each other — and on the way that following those wrappings around is a big part of what it means to grow up, or to survive growing up. Rachel succeeds in the beauty pageant — succeeds at becoming a woman — by using tactics traditionally associated with women. These include (as Richard Cook says), gossip, and (as Richard doesn’t quite say) trading on her body in order to gain allies and power and knowledge. (At the end of the book she says, ‘all my life i wanted to be able to do things, fix things, make things happen, without feeling like a conniving whore” — but of course her victory at the end, which gives her power and the ability to do things and fix things, arguably comes about because she’s been a very accomplished conniving whore.) Yet Rachel also succeeds, again, by recognizing where the penis isn’t — and by figuring out that the people who claim to have power over her are as phallusless as she is. And, in turn, understanding that maybe means she’s not so phallusless; she gets to put her finger through that ring, after all.

Lord Rod (which is an interesting name) gives Rachel a speech about fake books, and about how a truly accurate, undetectable fake can be more valuable than the real thing. Judith Butler, in her discussions of gender, says something similar — there is no original of gender, she contends, so copies of gender which show their copiedness, like drag, are more valuable, or truer than the “real” thing.

Rod is himself in doubled drag — a woman who looks like a woman disguised as a man who looks like a woman. And what about Rachel? Is she a woman pretending to be a woman? Is she faking having a phallus or faking not having one? And is she more valuable as a fake or as the real thing? If there’s an answer here, it seems like it’s neither that the phallus is truth nor that the phallus is false nor that there is no phallus, but some indeterminate, situational amalgam of all those things. Do we know Rod has no penis? Do we know Rachel has none? Only because McNeil tells us so. Drawings are what we say they are; their gender is made of knowledge, not bodies. Like ours, maybe, though it’s hard to know for sure. Once the story starts and the future turns to past, how can you tell the dancer from the dance?