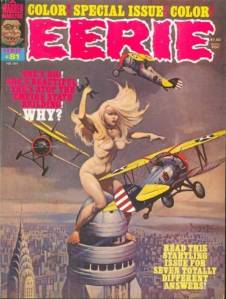

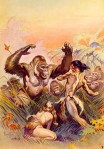

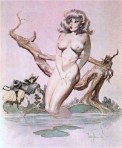

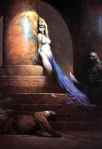

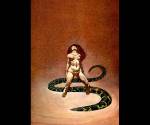

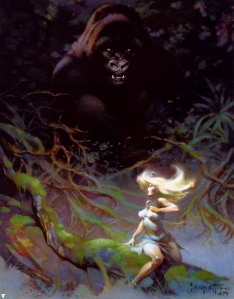

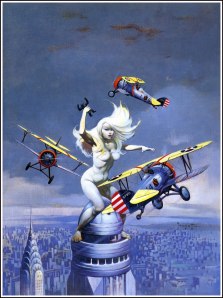

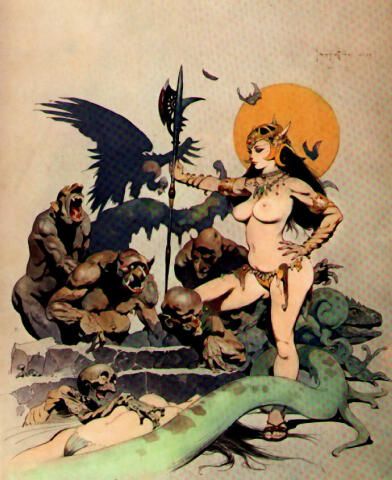

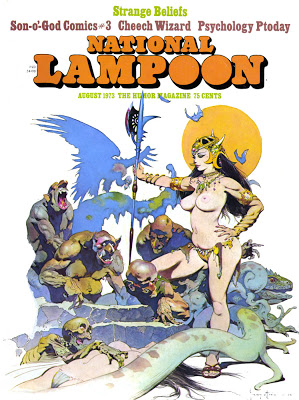

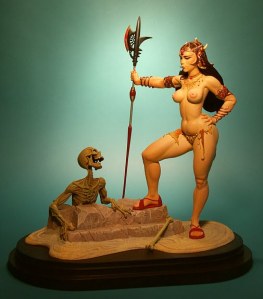

I don’t know what Warren Publishing had in mind when they commissioned Frank Frazetta’s “Queen Kong” in 1971, but Eerie devoted an entire issue to the image in in 1977. The cover of No. 81 declares: “SHE’S BIG! SHE’S BEAUTIFUL! SHE’S ATOP THE EMPIRE STATE BUILDING! WHY? READ THIS STARTLING ISSUE FOR SEVEN TOTALLY DIFFERENT ANSWERS!”

Each of the 5-10 page comics offers an explanation for Frazetta’s giant naked woman:

a) breast enlargement injections gone terribly wrong

b) espionage at the 2090 Worlds Fair

c) King Kong blood transfusion

d) “physiological freak”

e) lab-grown mutant engineered to terraform alien planets for colonization

f) giant robot suit

g) Little New York populated by tiny, human-imitating aliens

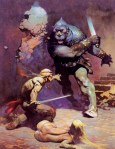

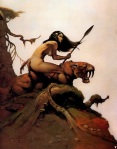

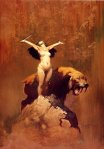

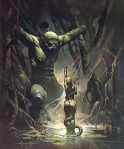

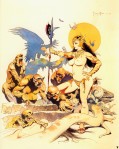

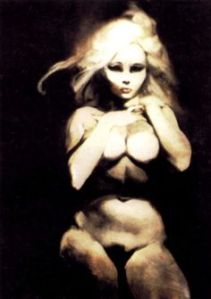

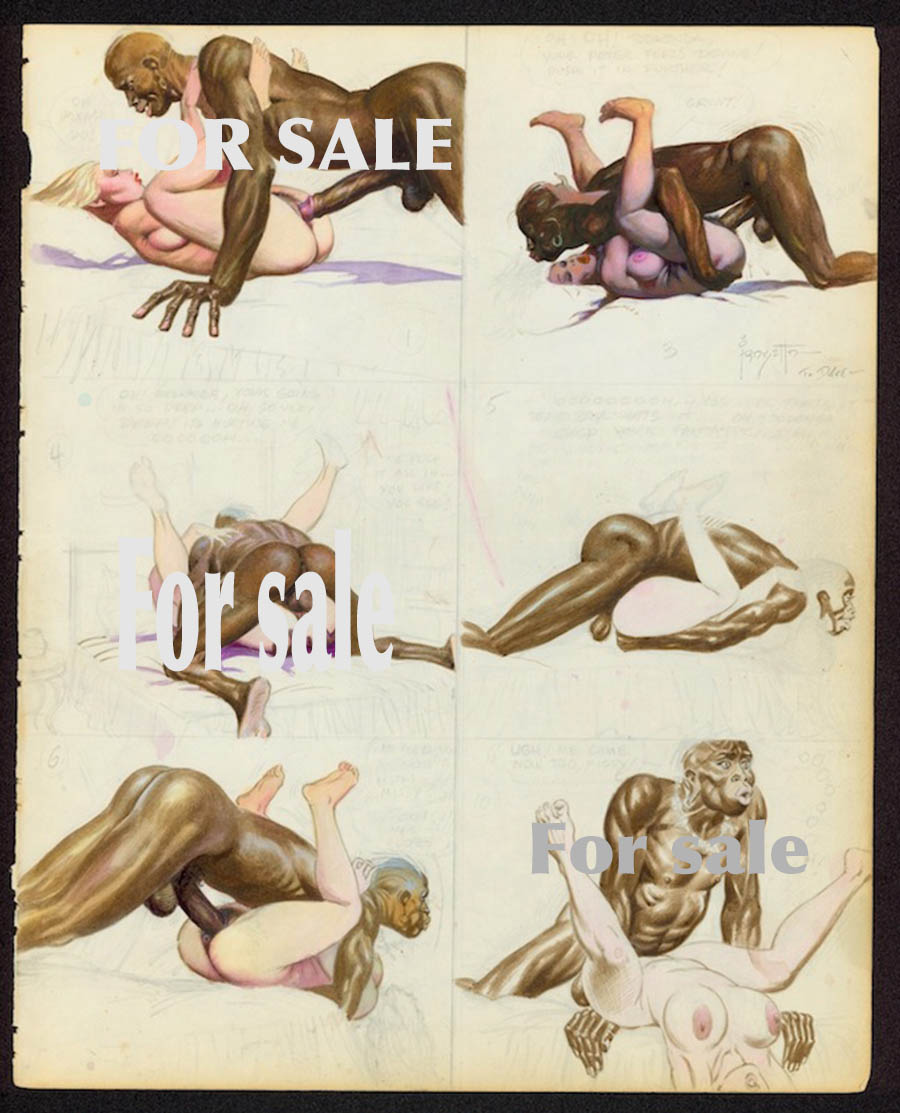

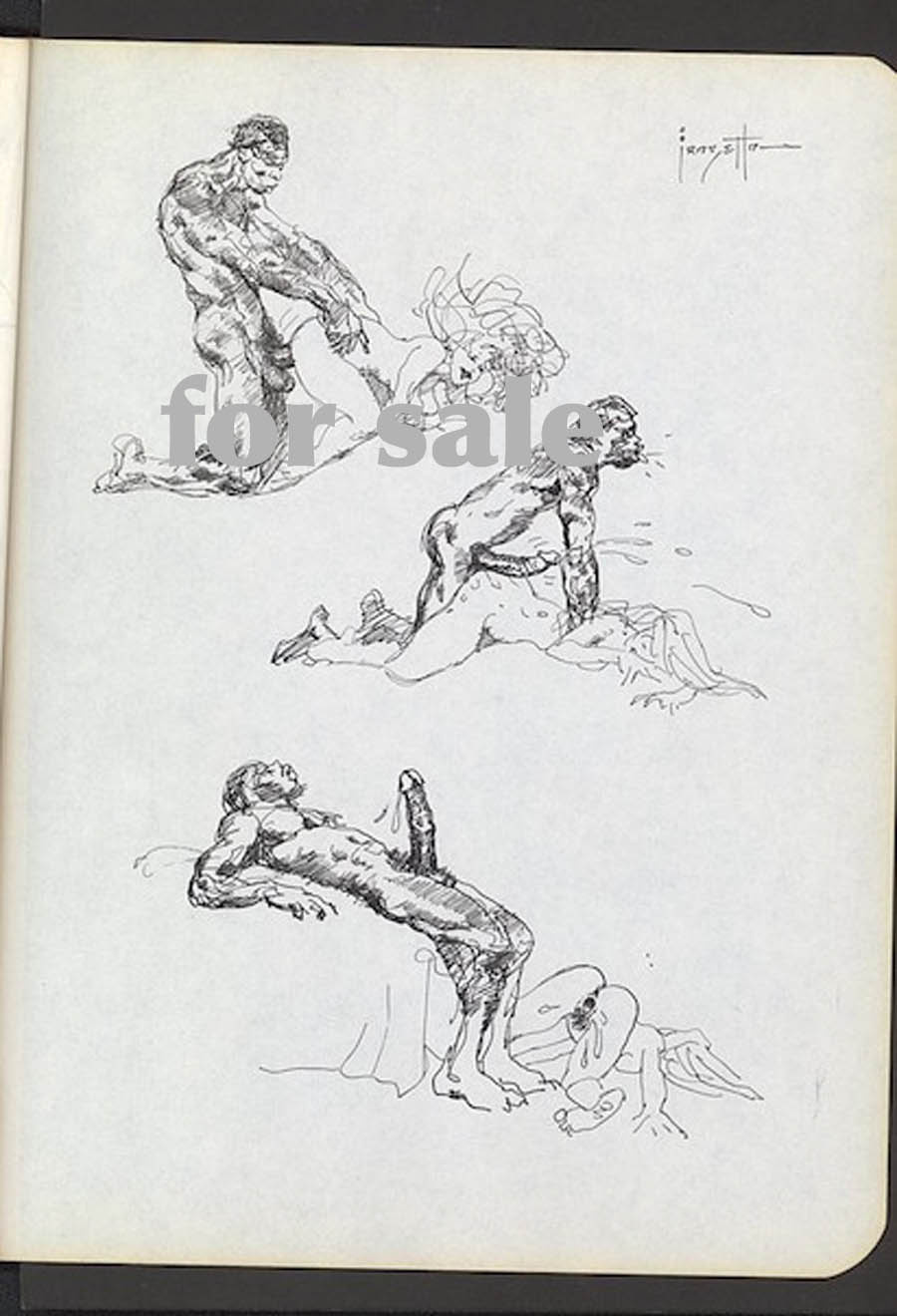

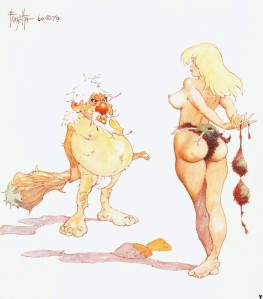

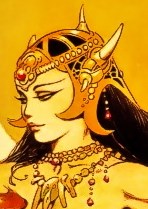

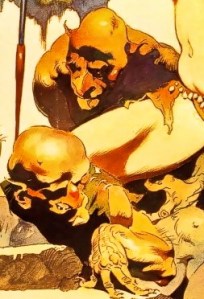

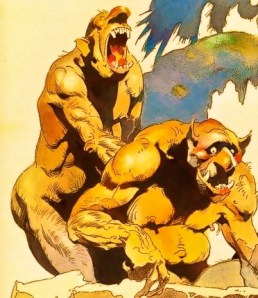

Explaining the ape in her fist proved even harder, but Queen Kong’s size isn’t her most fantastical quality. It’s her breasts, because a) perfect circles are only possible in space, and b) no nipples. The issue’s other artists offered their Frazetta imitations:

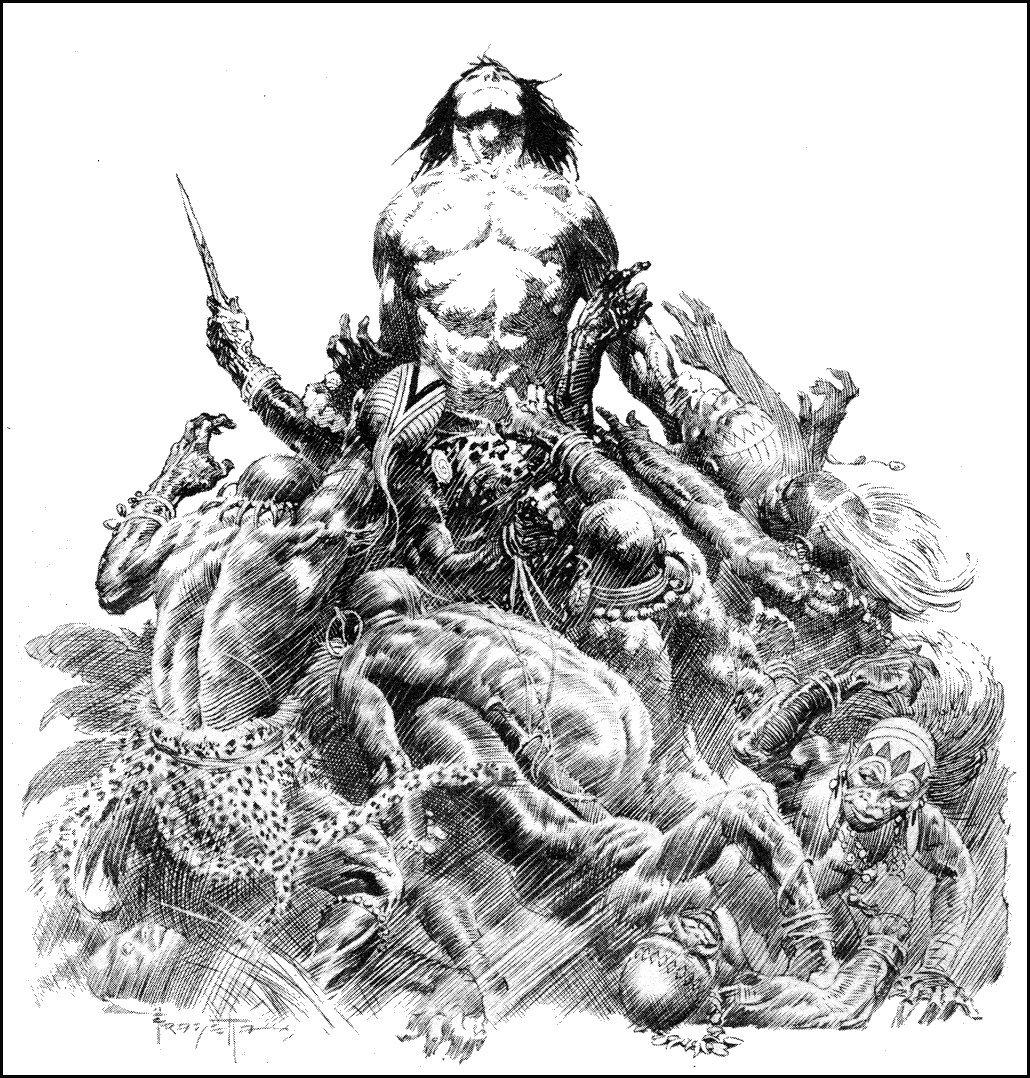

The first tale, “Goodbye, Bambi Boone,” I remember best, perhaps because the artistic style was so familiar. Carmine Infantino and Dick Giordano were renown artists at DC in the 70s, and both had just contributed to the 1976 DC-Marvel team-up, Superman vs The Amazing Spider-Man. The two heroes also battle atop the Empire State Building.

My copy was supposed to be signed by the two companies’ top editors, but it arrived with only Stan Lee’s faux-scribble on the cover because DC had just dethroned Infantino. He went from DC publisher to Warren freelancer. Giordano would become editor a few years later, but meanwhile both were earning extra paychecks by drawing naked women on skyscrapers.

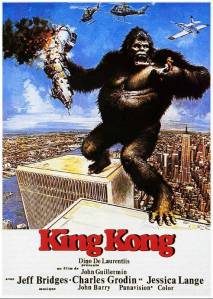

Infantino pencilled writer Bill DuBay’s “The Bride of Congo: The Untold Story,” the most comically subversive of the seven stories. Like Peter Jackson in his 2005 King Kong remake, DuBay depicts a Fay Wray deeply in love with her giant ape, and the two even elope and raise a family. Louise Jones and David Micheline give their Queen Kong a happy ending too, sending the colonizing starships away so the narrator’s genetically engineered mutant sister can live a peaceful life alone with her little monkey friends.

And that’s it for Queen Kong survivors. Roger McKenzie’s is just a machine operated by a thug for power and profit–which is as close to feminist allegory as Eerie gets. The rest of the writing staff murder their heroines, some more misogynistically than others. Cary Bates’ teary-eyed manager replaces biplane blanks with real bullets because his beloved actress was dying anyway. Bruce Jones’ mother-exploding freak dies unloved and alone after growing so large she displaces the Earth from its orbit. But Nicola Cuti’s finale is the worst of the batch–a tale of a money-obsessed “Golden Girl” whom aliens kill and then erect as a gold-embalmed statue of liberty.

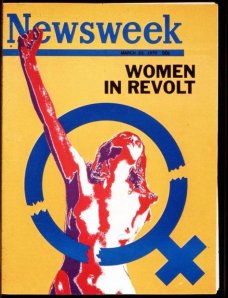

The stories strip Frazetta’s painting of any quasi-feminist edge by punishing its female hero-victim for her uppityiness. But Eerie and Ms. weren’t the only 70s magazines with nakedly revolting women on their covers. Newsweek began the trend in 1971, the year before Frazetta painted “Queen Kong.”

“Women in Revolt” triggered the first female class action suit when 46 Newsweek employees sued for sex discrimination the day the issue hit newsstands. The magazine allowed no women on its writing staff. A second suit followed in 1972, but this time the owner of the parent company, Katherine Graham, stepped in. Graham was friends with Gloria Steinem and the giant Wonder Woman who appeared on the cover of Ms the same year. Newsweek agreed that by 1976 a third of its reporters would be women, including a senior editor.

James Warren, the king sitting atop Eerie‘s 1977 masthead, made no such agreement. Of the sixteen writers and artists in No. 81, Senior Editor Louise “Weezie” Jones is the lone woman–Gloria Steinem was long gone. Jones entered comics in 1971 as the model for Bernie Wrightson’s cover for House of Secrets No. 92, edited by her first husband, artist Jeff Jones. She is fully clothed and only somewhat imperiled since hero and threat are ambiguously merged into the monstrous first appearance of Swamp Thing.

According to the Eerie bio page, she “worked in advertising/promotion before moving to Warren, where the thirty-year-old editor scripts an occasional story. She lives in Manhattan with her daughter.” “I was willing to work in any kind of publishing,” she told CBR. “One of my friends said there was an opening at a comic book company that paid more than the job I had!”

Jones (originally Alexander, later Simonson) was hired in 1974. She described the process of scaling the Warren skyscraper to Bleeding Cool: “I essentially twisted James Warren’s arm into giving me the line of books as an editor. . . . Warren said to me ‘Girls can’t do superhero comics.’. . . I just kind of rolled my eyes and said, Look, I will edit the line for six months on my Assistant Editor salary . . . So of course I did it and then he made me the editor of the line, then he made me a Vice President.”

In 1980, Jim Shooter hired Jones for Marvel, where she edited The Uncanny X-Men and New Mutants and created the supervillain Apocalypse (featured in the latest X-Men film). Marvel in the early 80s was still a “boys club,” she said, but “I was always kind of one of the guys.” Her pay was “as good as the guys around me,” she said, “as far as I knew.” Ultimately, she concluded, “gender doesn’t come into play if [your work is] good enough.”

After moving to DC in the 90s she was instrumental in the Death of Superman and the Reign of the Supermen story arcs, but aside from Red Sonja, she never worked on superheroines: “I had generally avoided doing female characters and being put on female character books — in part because I felt it was a great way to get stereotyped as a person who does female characters, and that’s all you do. . . . I kind of regretted that I hadn’t gone more in that direction when I was younger, because it was so much fun. But you do what you do.”

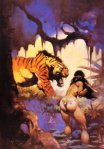

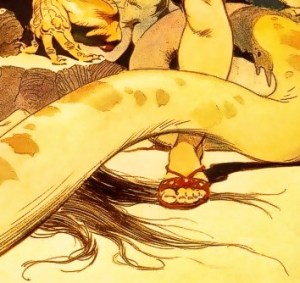

In Jones’ Eerie story “Starchild,” the mutated giant Janey does her job too, builds a city on a suitable planet for Earth’s growing multitude. But after a week of biblically hard work, she finds “acceptance” and “friendship”: “‘Cause y’see, Janey’d never had friends before. And those tittering monkey-things filled a gap in her childlike heart she never knew existed. . . . And for the first time in her prearranged life, she had fun. . . ”

“Starchild” offers Frazetta’s Queen Kong a happy ending, but unlike “The Bride of Congo,” the revolting giantess escapes even the fetters of marriage to live as a nurturing and playful God to the “monkey-things” of her adopted planet. Unlike King Kong, she is not a monster but the narrator’s secretly beloved sister. Her telling, however, receives only five pages, and so is the shortest of the issue’s tales. It is also fifth in sequence, denied the privileged positions of opening, closing, or colored middle story–all of which feature Queen Kong’s cathartic and/or admonitory deaths. “Starchild” is the best in the book.

“I think the women who make it in superhero comics don’t make it because they’re as good as the guys,” said Jones, “they make it because they’re better than the guys.”