Manfred on the Jungfrau, by Ford Madox Brown

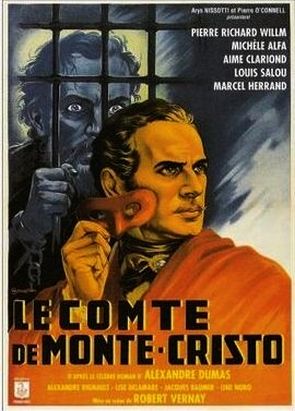

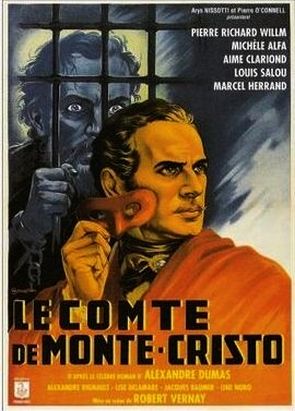

“In any case, one can state that much of the so-called Nietzchean ‘superhumanity’ has as its origin and doctrinal model not Zarathustra but the Count of Monte-Cristo, by Alexandre Dumas.”

– Antonio Gramsci, Letteratura e vita nazionale, III, ‘Letteratura popolare”.

This quote comes from Umberto Eco‘s introduction to the French translation of his 1978 book of essays, Il superuomo di massa.

As Eco elaborates:

I found Gramsci’s idea seductive. That the cult of the superman with nationalist and Fascist roots be born, among other things, of a petty bourgeois frustration complex is well-known. Gramsci has shown clearly how this ideal of the superman could be born, in the nineteenth century, within a literature that saw itself as popular and democratic:

“The serial replaces (and at the same time favorises) the imagination of the man of the people, it is a veritable waking dream (…) long reveries on the idea of vengeance, of punishing the guilty for the ills they have inflicted (…) “

Thus, it was legitimate to wonder about the cult of the right-wing superman but also about the equivocal aspects of the nineteenth century’s humanitarian socialism. [tr:AB]

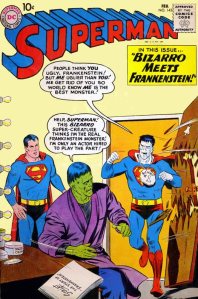

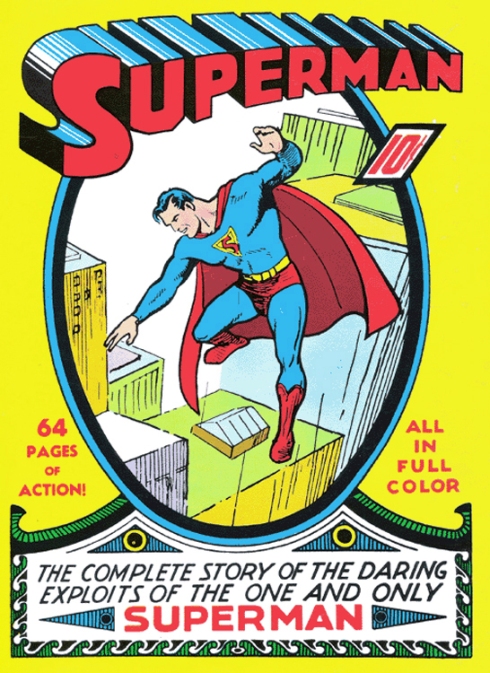

The French title of Eco’s collection is, aptly, De Superman au surhomme– ‘From Superman to the superman’.

But what of the reverse — how did we go from the superman to Superman?

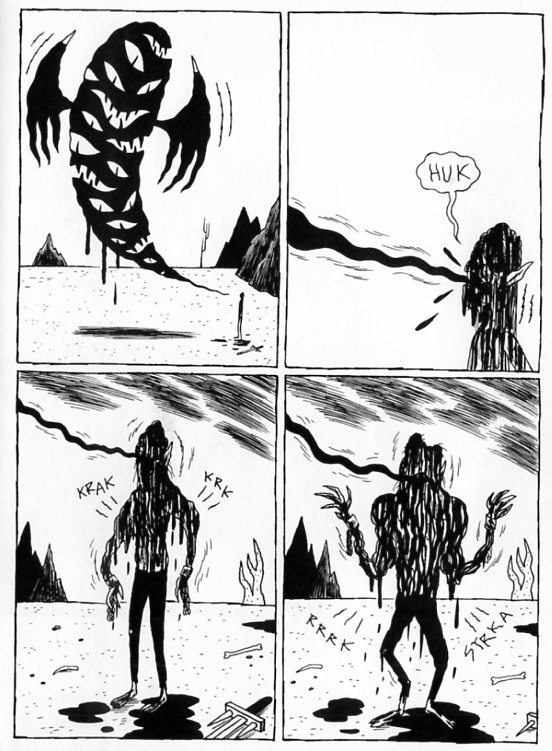

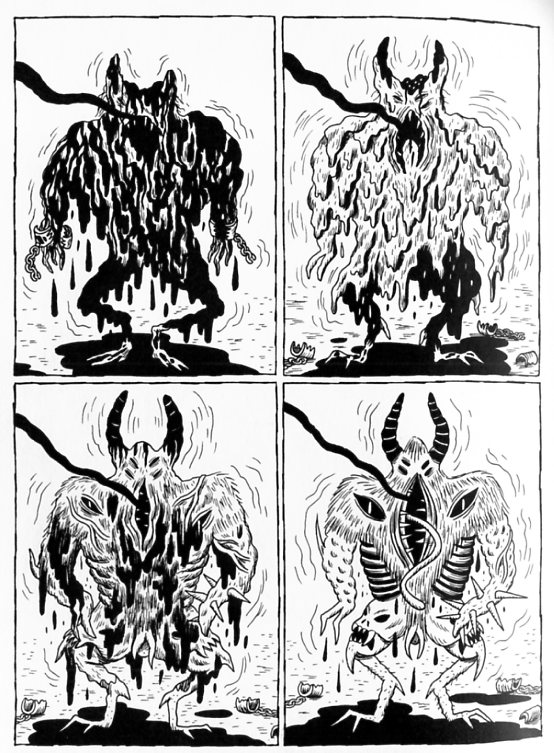

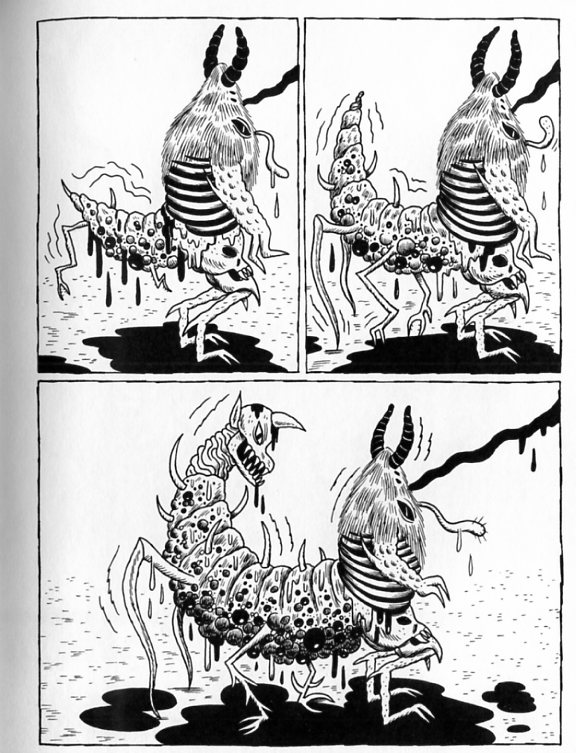

How did we get from here:

…to here?

Art by Joe Shuster

The superhero is one of the strongest — and strangest– modern pop charactertropes; I propose we dig into its roots– which I maintain go back to the 18th century’s massive cultural shift: a revolution in politics, thought, and culture.

The superhero is an ultimate narcissist fantasy of identification; it thrives in a modern world of atomised society, where the basic unit is the individual to a historically unheard-of degree. Thus we’ll start with the centuries that enshrined individualism, the better to give a cultural context to our enquiry.

We’ll also examine why the superhero is so dominantly an American cultural artifact; this will lead us into some dark territory.

First, though, we must distinguish the superhero from his heroic predecessors in myth and legend.

The Classic Hero

The idea of the superman was spawned in the 18th and 19th centuries. This statement may strike the reader as historically false; what of the superhuman heroes of myth and legend, Gilgamesh and Enkidu, Herakles and Achilles, Roland and Rustam, Cuchulain and Tomoe Gozen?

Heracles Farnese

These heroes were enmeshed in the fabric of myth. They were part of the structure of society, of the “great chain of being” that descended from the divine to the infernal, through the human; many were demi-gods, the legitimacy of their power stemming from godly parentage. Others were avatars of a warrior culture– linked through duty and right to the formal, “ordained” structure of the polity: for example, the knights of King Arthur’s Round Table, or the Argives besieging Troy.

What the classic hero was not was an individual.

Indeed, when the hero asserted his individuality — repudiating or even betraying the obligations that hampered and enmeshed him — the result was tragedy. The Greeks spoke of a person’s hamartia, or fatal flaw: very often, this took the form of hubris, pride or ambition so excessive as to invite divine wrath:

“Seest thou how God with his lightning smites always the bigger animals, and will not suffer them to wax insolent, while those of a lesser bulk chafe him not? How likewise his bolts fall ever on the highest houses and the tallest trees? So plainly does He love to bring down everything that exalts itself.”

– Herodotus, History

Thus Herakles, after drunkenly massacring his family, is punished by enslavement to his enemy Eurystheus; Achilles in his anger withdraws from the Trojan war, so imperilling his fellow Argives and bringing about the death of his lover Patrocles.

Sir Lancelot betrays his liege, King Arthur, by taking the king’s wife as a lover: the kingdom is subsequently torn apart by civil wars. The mighty warrior Roland is trapped with Charlemagne’s rearguard at Roncevalles by an overwhelming force– but pride stops him from blowing his horn to summon help until it is too late, and his army is killed to the last man.

Too late, Charlemagne

To deviate from duty, from his proper place in the scheme of the world, brings about the hero’s downfall and inflicts disaster on the community.

This is decidedly not the fate of the new character type– the superman.

The Birth of the Individual and the Coming of the New Hero

We have undertaken to discourse here for a little on Great Men, their manner of appearance in our world’s business, how they have shaped themselves in the world’s history, what ideas men formed of them, what work they did;–on Heroes, namely, and on their reception and performance; what I call Hero-worship and the Heroic in human affairs.

(…) For, as I take it,Universal History, the history of what man has accomplished in this world, is at bottom the History of the Great Men who have worked here.They were the leaders of men, these great ones; the modellers, patterns,and in a wide sense creators, of whatsoever the general mass of men contrived to do or to attain; all things that we see standing accomplished in the world are properly the outer material result, the practical realization and embodiment, of Thoughts that dwelt in the Great Men sent into the world: the soul of the whole world’s history, it may justly be considered, were the history of these.

Thus Thomas Carlyle (1795 — 1881) in Heroes and Hero Worship (1840). For Carlyle, the sole true root of human progress was that man who could rise above the mass, transcend his time and shake the world into a new form– the Hero. Examples he cites include Muhammad, Cromwell, Shakespeare, and Napoleon.

Unlike classic heroes, these men were not the servants (if often rebellious ones) of fate: they shaped fate. They stood above it.

The individual as giant was the logical extrapolation of the individual per se, who had in the eighteenth century assumed an importance never before acknowledged:

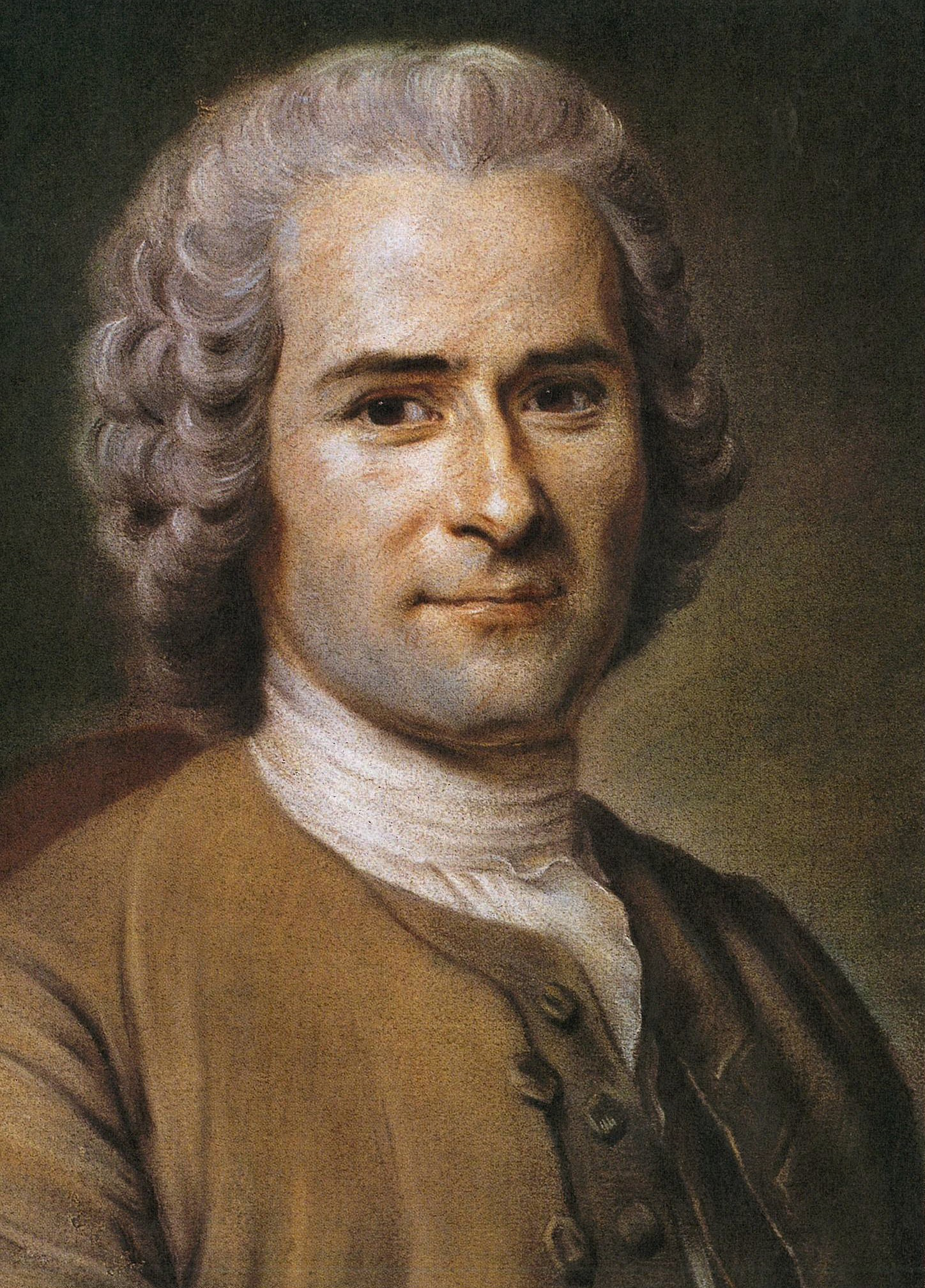

I have entered upon a performance which is without example, whose accomplishment will have no imitator. I mean to present my fellow-mortals with a man in all the integrity of nature; and this man shall be myself.

I know my heart, and have studied mankind; I am not made like any one I have been acquainted with, perhaps like no one in existence; if not better, I at least claim originality, and whether Nature did wisely in breaking the mould with which she formed me, can only be determined after having read this work.

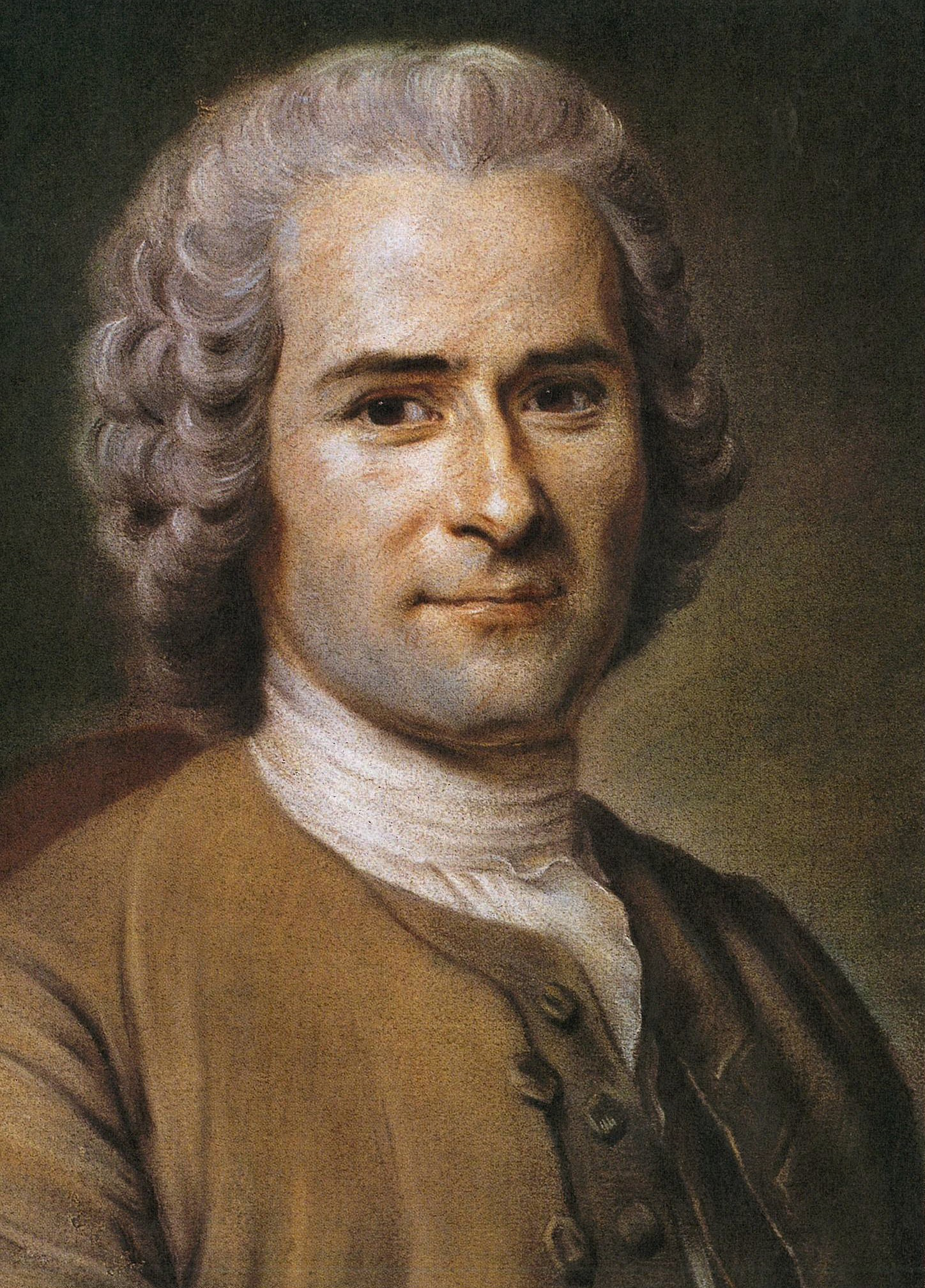

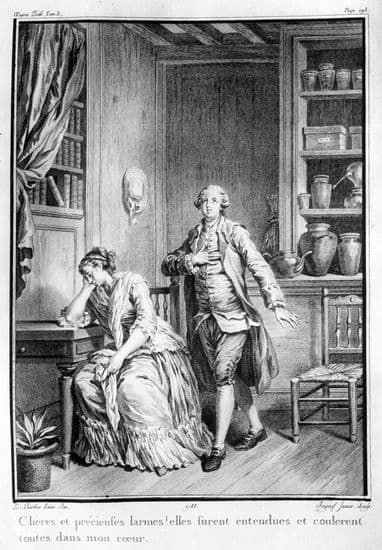

These are the opening words of the 1769 Confessions of Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712 — 1778).

Portrait of Rousseau by De la Tour

It was something unheard-of: the Self as subject, in all its raw nakedness, faults and all.

The rise of the individual found political expression in the Enlightenment, as well. The notion of his or her personal rights was enshrined in such foundational documents as the Bill of Rights of the United States Constitution and the French ’ Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen’.

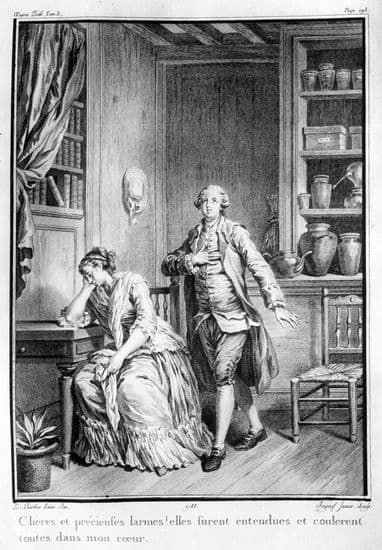

Individualism also flourished in the wider culture. The school of sentimentality in literature, as typified by Johann Wolfgang von Goethe‘s The Sorrows of Young Werther or Laurence Sterne‘s A Sentimental Journey, valued the enjoyment of emotion for its own sake– not as a source of empathy or catharsis. In parallel, the psychological novel was born — examining the inner life of the self.

The Italian innovation of the apartment, intimate, cosy and — above all– private, began to supplant the old houses and manors where many generations of different families and classes would live together.

Diners were less and less eating à la française, seated at large banquet tables and sharing from common dishes: in the new restaurants, they could be seated and served alone, at their own separate tables.

Dinner service à la française

The dance craze that was sweeping Europe was the waltz; in contrast to the group dances such as the pavane or the quadrille theretofore prevalent, couples twirled alone.

Even so seemingly trivial detail as shoe size underwent the individualistic evolution; in prior centuries, shoes were undifferentiated between left and right foot, and came in few standard sizes. Now cobblers were literally tailoring each piece of footwear to the specific foot.

Yes, heady times for the individual! All the headier after the French Revolution sent shock waves rocketing through Europe, ripping up the ancient structure of the world, bringing terror and war in its train.

The old order was shattered; the new citizen was deprived of “natural” superiors to look up to, the King, the aristocrats and the clergy. This was a vacuum waiting to be filled.

Came the moment, came the man — the Hero as Carlyle later conceived him, who bent the forces of history itself to his will; the true progenitor of the superman– Napoleon Bonaparte.

Napoleon crossing the Alps, by David

The armies of revolutionary France were marked by a new kind of professionalism: an officer’s commission was no longer secured by genteel birth or outright purchase. Thus men rose in the ranks through merit– and in the case of the artillery lieutenant Bonaparte, he would rise to the throne of the world’s mightiest empire.

Nothing seemed able to stop him; destiny was clay in his hands; nations fell or were born at his word. He elicited worldwide admiration even from his enemies. (To this day, the British, his most tenacious foes, allude to Waterloo as if it were a defeat — ‘He met his Waterloo in the 2008 election’– rather than the greatest victory in British history; and it is a compliment to call a man, say, ‘the Napoleon of finance’.)

Wordsworth, Goethe, Beethoven, Byron– they were excited by this seemingly superhuman figure who was poised to sweep the old corrupt order onto the trash-heap of history.

(Great was their disgust and sense of betrayal when the former revolutionary crowned himself emperor:

O joyless power that stands by lawless force!

Curses are his dire portion, scorn, and hate,

Internal darkness and unquiet breath;

And, if old judgments keep their sacred course,

Him from that Height shall Heaven precipitate

By violent and ignominious death.

–Wordsworth, 1809

The moral being: don’t expect too much from supermen, and you’ll not be disappointed.)

It is a cliche of the lazy writer or cartoonist to depict a lunatic as one persuaded he is Napoleon; yet there have been hundreds of such cases documented, from Napoleon’s own time to the present, attesting his power over the imagination. Napoleon himself was a canny curator of his own image. That famous pose with the hand tucked under his shirt? It was suggested to him by an actor. That hat? He had dozens of them, to be left as souvenirs wherever he travelled.

(He is also the exemplar for world-conquering villains; there is a direct line of descent from Napoleon to Doctor Doom.)

Napoleon formed a template for the superman; and he further smoothed the path for the latter by radically institutionalizing meritocracy, “career open to talents” as embodied in the Grande Ecole schools of France or in the University of Berlin, institutions of excellence set to turn out the genius leaders of tomorrow.

A new elitism was in the shaping, and the idea of the superman largely sprang from it into the cultural zeitgeist.

Masters of Nature

Welch erbaermlich Grauen Fasst Uebermenschen Dich?

[What vexes you, oh superman?]

— Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, Faust (1808)

The eighteenth century was also marked by a growing mastery over the physical world. The very idea of progress flourished as never before; for most of history, it was thought that mankind had regressed from a long-vanished golden age. (Mark how the classic heroes all belonged to the past.) Human beings now, however, were going from strength to strength with no end in sight.

This was the age of the Industrial Revolution. Steam power gave men the might of Titans; nature seemed to yield more and more of its secrets to the natural philosophers not yet given the new name of “scientists” ( coined in 1833).

Let us consider the below painting, An Experiment on a Bird in an Air Pump, painted in 1768 by Joseph Wright of Darby (1734 – 1797):

click image to enlarge

A cockatoo is trapped in a glass jar from which the air is gradually pumped out, leaving the bird slowly to die, suffocating in the vacuum.

Note the two weeping little girls to the right, distressed by such cruelty; but one of the experimenters is at hand to explain how this suffering is necessary for the progress of science. The other experimenter stares out at us — challenging us, perhaps, to dare contest his will to knowledge.

This painting presages another avatar of the superman: the scientist, wresting control of the secrets of the universe as the titan Prometheus stole fire from the gods.

Yes: a modern Prometheus… as an 18-year-old Englishwoman dubbed her fictional challenger of Heaven:

So much has been done, exclaimed the soul of Frankenstein — more, far more, will I achieve; treading in the steps already marked, I will pioneer a new way, explore unknown powers, and unfold to the world the deepest mysteries of creation.

–Victor Frankenstein, in Frankenstein; or, the Modern Prometheus, by Mary Shelley

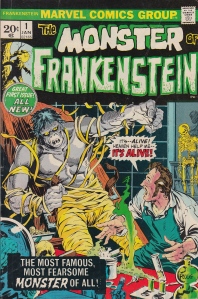

Frankenstein and his monster; illustration by Theodor von Holst

Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley (1797 – 1851) published her novelFrankenstein; or, the modern Prometheus in 1818.

The title hero usurps God’s privilege by creating life: a monstrous, manlike creature endowed with reason.

Yet, to do so, Frankenstein eschews the occult, magical methods of the Fausts of previous fiction. His power derives from a mastery of the elements attained by rational study and experiment– from science. He aims to join that near-Godlike elite of researchers so admiringly described by his teacher Waldman:

They ascend into the heavens: they have discovered how the blood circulates, and the nature of the air that we breathe. They have acquired new and almost unlimited powers; they can command the thunders of heaven, mimic the earthquake, and even mock the invisible world with its shadows.

– Shelley, op.cit.

No need for bowing to demons to do his bidding. Frankenstein is free of God and Satan alike. (Shelley was, in her youth at least, an atheist.) He replaces God, in fact; and though the novel shows him punished for his deeds, it is clear that his destruction comes not from a vengeful heaven, but from his own flawed character– Shelley, like her female equivalents in the Darby painting, could see the cruelty in the scientist’s will to power.

Victor Frankenstein points forward to other, future ‘scientific superman’ characters; to Verne’s Captain Nemo and Robur the Conqueror, to Wells’ Griffin (the Invisible Man) and Dr Moreau, to countless Mad Scientists and scientific heroes like Tom Swift, Doc Savage or Captain Future.

(As for his tormented monster spawn, he too has superhero descendants, in the ‘monstrous’ vein: the Heap, the Hulk, Swamp Thing…)

Indeed, many literary historians credit Mary Shelley with creating a new literary genre: science fiction, of which more anon. She was also writing within the perimeters of another new genre: the Gothic.

Romanticism and the Gothic Backlash

Not everyone welcomed the new industrial age. The rapid changes of the modernising world alarmed and alienated people of all classes. There came to be a yearning for nature, for sublime landscapes and ruins, for an idealised past; to the cold new rationality were preferred the warmth of feelings.

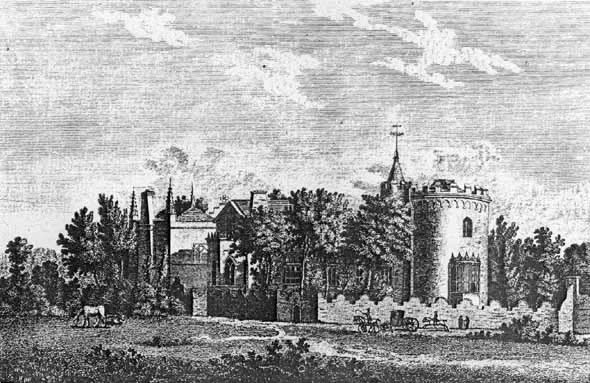

The literary expression of this backlash was the Gothic novel, the first of which is generally agreed to be that of Horace Walpole (1717–1797), The Castle of Otranto.

Walpole’s neo-Gothic castle, Strawberry Hill

There followed a flood of spectre-haunted volumes, many of which featured brooding predecessors of the superman: the title character of William Beckford’s The History of the Caliph Vathek, who dares to invade Hell; Charles Maturin‘s Melmoth the Wanderer (1820), a damned, dark near-immortal; Lord Byron‘s Faust-like Manfred, who defies God and Satan alike; and perhaps the most proleptic of all, Byron’s secretary John William Polidori‘s The Vampyre (1819).

The Gothic novel was also the first narrow commercial genre of popular fiction.

The nineteenth century saw the rise of the first true mass media, and the birth of literature for the masses; Polidori’s book will serve as a useful transition to the next chapter.

Next, in Part 2: The true birth of the superman.