In her recent post on the postmodern sublime in comics, Marguerite Van Cook paraphrases Frederic Jameson on our crazed cultural landscape.

Jameson points out that the sublime of postmodern is not the dark and brooding place of the high romantics; it is not the depressed world of brooding heroes. Somewhere along the line, all of that angst and personal introspection has been replaced by another world of bright shiny surfaces, replicas and fragmented visions in a world now experiencing another kind of psychic onslaught. Jameson talks about the postmodern sublime as a type of container for all this madness, which he describes as a type of schizophrenia.

Marguerite goes on to look at various comic-book chroniclers of the post-modern sublime, concluding with Al Columbia.

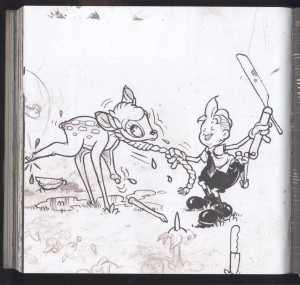

Al Columbia’s Pim and Francie perhaps sums it all up. They run not walk to the sanatorium. Columbia’s characters are no longer in revolt, they are beyond that cognitive choice. Rather they live in a world that does not differentiate morality and feelings. Columbia draws snatches from various artists styles. They hover ghostlike, pulled back from our collective memory as they sit on pages that are torn, fragmented and abused in a confrontation of what it means to be a new product. Jameson suggest that nothing is left to shock us, but I’d suggest that Al Columbia does just that. In this final image the boy takes a straight razor to Bambi. He eschews the choice of Mickey and assaults us in the soft spot. Bambi, the sacred lamb, the sacred cow, the holy sanctified symbol of innocence, is offered to the madness of the postpostmodern. Bambi’s limbs lie dismembered in the grass and we are oh so close by, to see them.

Jameson, Marguerite, and Columbia are all presenting us with a postmodernism as hell; a shiny, emotionless strobing of patterns whose only meaning is an ersatz copy of meaninglessness. The real has vanished utterly, and all that’s left are images of images, a cardboard graveyard of stale tropes through which wander wayward consumers, robbed of even the dignity of despair.

That is certainly one face of postmodernism…but I wonder if it’s really the most insidious one. To me, anyway, the focus on the postmodern schizophrenic apocalypse can obscure maybe the most obvious thing about our current cultural moment — which is that postmodernism is really pleasurable. Gliding out on those ever-shifting shallows, with the real and its hierarchy of earnestness vanishing like the afterimage of that web page you just left, while every song in the world is simultaneously uploaded to your cortex — who can resist such blithely excessive dreams?

Comics is so rooted in nostalgia that it maybe makes sense that it sees the post-post-everything as an impetus mostly to gnash and mourn and re-reject decades old funny animals and the now irrelevant sentiments they inspired. Other cultural forms, though, have embraced the zeitgeist with more eagerness.

Electronica is perhaps a too-obvious example. Listening to the recent release Tipped Bowls by Taragana Pyjarama, you aren’t dumped into a schizophrenic void. On the contrary, the first track, “Four Legged,” orchestrates the future-synth automatons of our overdetermined dreams into a rising symphonic rush of exaltation, panning and swooping over digitized fijords like tiny joyful digitized tourists. “Growing Forehead” takes that most human of sounds, an inhaled breath, and cuts and reiterates it until it’s just another computerized meme afloat in ecstatic programmable melody; transcendence as binary conversion. “Pinned (Part 1),” is a staggering agglomeration of beats and bloops, like a video game caught in a spin cycle, while “Pinned (Part 2) is a funkier but still inner-ear-disturbed strut, stochastic patter resolving and threatening to dissipate, resolving and threatening to dissipate, all with a catchy tunefulness, as if we’ve wandered into a world where even the busted appliances spit out pop.

That world is our world, of course; high culture and low culture and random furniture and passing cats (especially passing cats!) all sliding across one endless screen. It’s nauseating and soul-destroying, certainly. But it’s also vertiginous and, in a song like “Ballibat,” such a lovely, smoothed-out mash-up of timeless futurism that you wonder if, in this post-present, you even need a soul.