“There’s only one Hamlet (and most children don’t read it), whereas comic books come by the millions.”

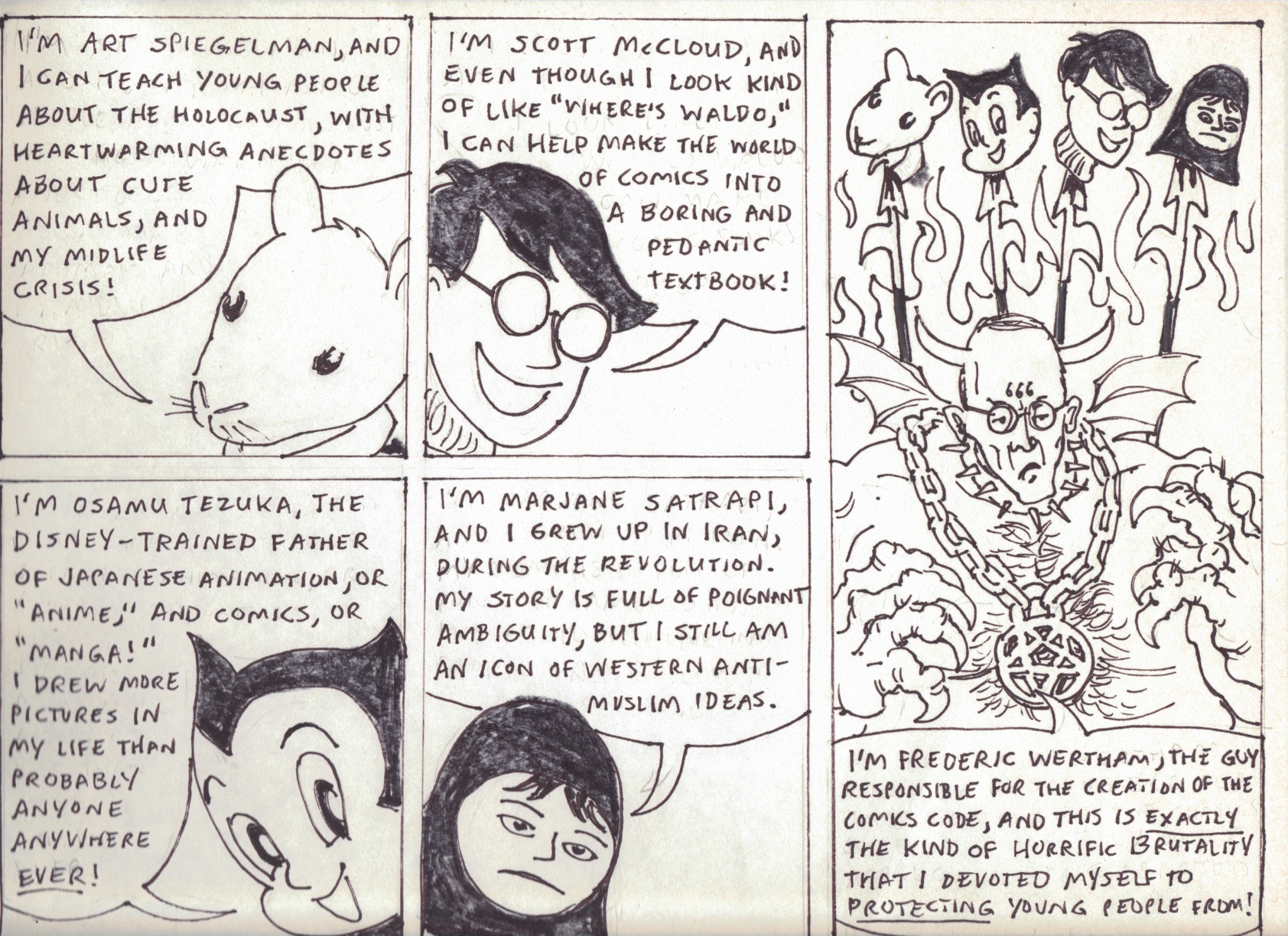

That’s what Frederic Wertham told readers of National Parent-Teacher in 1949, his second of three reasons why comics are bad for kids. Six years later in Seduction of the Innocent, he quoted a publisher using the same Shakespeare play as an excuse for comic-book content:

“Sure there is violence in comics. It’s all over English literature, too. Look at Hamlet.”

Wertham roundly mocked the comment, but the publisher had a point, and not just about violence. Lone heir of an aristocratic family avenges his murdered father in a society ruled by corruption. Sound familiar? Hamlet is the boiler plate for Batman and other vengeance-motivated vigilantes across the multiverse.

So while it’s true most children don’t read Hamlet, Hamlet knock-offs come by the millions. But if you don’t think Batman is a Tragedy, take another look inside Shakespeare.

Bruce Wayne, haunted by the unjust death of his parents, dedicates himself to a noble war on criminals. Does that make Bruce a tragic hero? Depends on your definition. Hamlet is a tragic hero in the sense that he is the hero of a tragedy. Macbeth is also the hero of a self-titled tragedy, but the two characters are polar opposites. Macbeth overthrows the peaceful order of Scotland by murdering the king and stealing the throne. In Hamlet, that’s Claudius, the guy who murdered Hamlet’s dad and set his ghost wandering the ramparts. It takes the not-of-woman-born Macduff to defeat the usurper Macbeth and restore order. In Denmark, that’s Hamlet’s vigilante mission.

The ur-Tragedy Oedipus Rex combines the roles of Macbeth and Hamlet into one character. Oedipus is the supervillain who killed his own father, stole his father’s wife and throne, and sunk the city of Thebes into supernatural plague. But he’s also the hero who solves the mystery and restores order by punishing the criminal—which means gouging his own eyes out. If you define “tragic hero” as that sort of a self-punishing criminal, neither Hamlet nor Macbeth make the list.

But Hamlet, like Batman, is an avenger. He didn’t make Denmark rotten. That was Claudius, and if Claudius self-punished like Oedipus, Claudius would be a tragic hero too. But Claudius is just a garden-variety villain, and so Denmark needs a hero to set things right. Enter Hamlet. He’s “tragic” only in the sense that he dies, and since he dies after completing his heroic mission, he dies triumphant. But unlike the deaths of Claudius, Oedipus, and Macbeth, his death isn’t necessary to restore order. It’s just an epilogue.

Unlike tragic heroes who start out unjust and so corrupt their kingdoms before eventually punishing themselves, an avenger is aligned with justice from the start. Hamlet is “tragic” only because he ends in what Northrop Frye calls social isolation. The most extreme version is death—six feet under is pretty isolated—but social isolation comes in a range, and avengers embody it all. John Shelton Lawrence and Robert Jewett in The Myth of the American Superhero identify the standard type: “lonely, selfless, sexless beings” each of whom “never practices citizenship.”

Your traditional gunfighter doesn’t settle down after restoring order. He moves on. Which implies the role of avenger is socially subversive in itself. Because the avenger is a response to injustice, the avenger reflects and embodies that injustice. Once the criminal is punished and justice restored, the avenger also has to conform to tragedy’s ABA structure. His own pre-hero state has to be restored too. It’s a mini-version of society’s former golden age, an age free of crime and so also free of crime-fighters. A full restoration of justice ends the role of the justice-seeking avenger, and so the avenger has to vanish with the villain.

To end in social integration instead, an avenger has to give up the avenger role. That means hanging up the costume and getting married—how early proto-superheroes Zorro, the Gray Seal, and Spring-Heeled Jack all ended their crime-fighting adventures. Serial heroes like Batman remain avengers by prolonging the B phase of the tragedy plot structure, that quixotic war on criminals that by definition can never end. If Bruce just needed to hunt down his parents’ killer, he could have retired a long time ago and married Julie. Remember Julie? Probably not. She was Bruce’s original fiancé, but, like Ophelia, Julie called it quits long before the end of the action.

Other avengers at least pretend to be on a simultaneous quest for personal restoration. Superheroes often figure their fantastical abilities as blessings for society, but curses to themselves, and so their ongoing serials project a desire to give up their powers and live a normal life. Alan Moore mocked this idea when he took over Swamp Thing, calling “the premise of a monster trying to regain his humanity” flawed because

“if that were to happen, the series is over. The dimmest reader realizes that isn’t going to happen, meaning the character is going to spend the remainder of the series on the run, moping about what was not happening. So Swamp Thing ends like Hamlet or just a Silver Surfer covered in snot.”

Hamlet, grandfather of monstrously moping superheroes, is a prototype of the isolated avenger whose identity is too defined by the avenging mission to give it up. Once he has completed the mission assigned to him by his father’s ghost and restored justice to Denmark by punishing his mother and usurper uncle, Hamlet’s death eliminates the last traces of Claudius’s corruption.

Hamlet could instead “regain his humanity” and reenter society by marrying, but Ophelia dies because her boyfriend can’t stop being a hero—the same way Spider-Man would never willingly cure himself of his power-bestowing mutation. Marrying Ophelia before completing his mission would turn Hamlet into a failed hero or, worse, a villain, just another guy willing to be a citizen of a corrupt town. Like Batman, Hamlet can’t settle down till he’s scraped the rot out of Denmark. Lamont Cranston tells his fiancé the same thing: he can’t marry until he has completed his avenger mission as The Shadow, making Margo Lane an Ophelia who avoids death by accepting endless delay through a serial form’s never-ending B structure.

Which is a long way of saying: No, Frederic, there’s more than one Hamlet, and millions of fans do read them.