There’s a strange phenomenon that sometimes happens in later seasons of television shows, where the weight of all of those previous years occasionally produces moments of metadialogue. It frequently appears as part of an effort to cope with the sheer unlikelihood of seven seasons of drama, the typical string of intensely emotional events which is unpunctuated by moments of normal, boring, every day life. A few weeks ago on Grey’s Anatomy, for example, a newer doctor asked sort-of protagonist Meredith Grey why Alex Kharev, one of the other remaining original characters, seems like such a jerk. “He’s been through a lot,” answers Meredith. “He had a girl go crazy on him, his wife almost died and then she walked out on him. And then he was shot and almost bled to death in an elevator.” It’s a weird moment; not only does it puncture the shoe’s admittedly-thin veil of plausibility (no one has that level of wackadoo tragedy happen to them in such a short span of time), but Meredith’s wryly explanatory list just draws attention to the oddity of Alex’s excessively eventful life. Grey’s Anatomy seems to be doing its best to brush over this bit of patent fictionality by hiding it in plain sight, but it’s hard to imagine writing or hearing the line without immediately recognizing the show’s artifice. Once you start looking for this kind of dialogue, you see it everywhere – detectives on cop shows grouse about how many dead bodies they see in a year, characters joke about that one time a few years ago when they were buried alive, long lasting characters look around and comment on the number of new hospital staff members after a particularly disruptive cast turnover. One of the characters on another Shonda Rhimes show, a therapist named Violet, frequently bemoans her bad luck, and at one point even asks – “Why does this sort of thing keep happening to us?” Because you’re on a primetime soap opera, Violet. Happiness does not make for good plot.

There was a particularly good example of this kind of metadialogue on the J.J. Abrams show Fringe a few months ago. (*Ahem*: Major Fringe spoilers ahead, if you’re concerned about that sort of thing). Fringe has undergone a pretty monumental transformation from the show that first appeared to the show currently airing on Friday nights. Initially, Fringe followed a formula made familiar by The X-Files, a police procedural with added supernatural elements – monsters and the unexplained spring out of the woodwork, and an eccentric, intrepid team of curious investigators searches for the reasons why (and the ways to stop it). Most new episodes came packaged with a new supernatural event which was handily dispatched by the hour’s end, and although some characters and plotlines hinted at a deep, dark secret in the background, that secret functioned asymptotically. Stories seemed to continually approach the point of uncovering the series’ organizing mystery, but they drew closer and closer without ever arriving at the mystery’s content.

Nothing says procedural like a cop in a doorframe holding up a badge

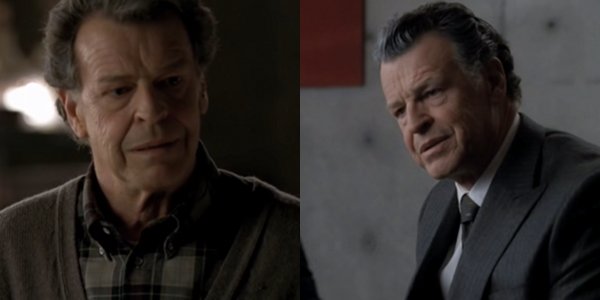

At some point during its second season, though, Fringe took a sharp right turn into the weird (and arguably, the better). Olivia and Peter, investigators of “fringe science,” along with Peter’s fabulously off-kilter mad scientist father Walter, discover and then travel to a parallel universe (the existence of which provides the underlying explanation for many of the previous season’s strange phenomena). The other universe, or “Over There,” is home to many doppelgänger versions of Fringe‘s original characters, including a much more fun-loving and freewheeling Olivia (who Peter dubs Faux-livia) and a powerful, sane version of Walter (Walternate). As it turns out, the rules of Over There are different from our own, and the course of history has shifted slightly, leading to the complete quarantine of Boston and much of the Midwest, a militarized society, a gold rather than green Statue of Liberty, and the continued use of zeppelins. (Zeppelins!)

Walter vs. Walternate

The great thing about Fringe‘s Over There is that its entertaining, superficial differences also come with a new set of narratological paradigms. As Peter and Olivia discover, the breach between universes has led to the alternate universe’s gradual disintegration, and Walternate’s method of holding his world together frequently involves trapping thousands of unfortunate, innocent citizens in a timeless, motionless state – literally frozen in amber – in order to prevent the universe from unraveling. The stakes are much higher, and those simple Monster of the Week plotlines are no longer sufficient to represent or address the other universe’s terrifyingly fragile state. In their own universe, Peter and Olivia encountered and dispatched isolated pockets of oddity, leading to the show’s episodic and frustratingly static structure, but Over There, a monster is never just a single event. Any deviation from the standard laws of physics is a potential site of total, universal dissolution, and unless it can be stopped, hundreds or thousands of people could die in order to keep the world from simply falling apart. As a result, the show has drifted away from its initially episodic structure into something more serialized, allowing plots to expand beyond the boundaries of an hour to keep pace with the long-term goals of the main characters Over There, who have plans to save their universe that necessarily exist outside the moment of an individual bizarre occurrence.

I should mention that although the other universe introduced an entirely different set of narrative possibilities for the show, Fringe has not abandoned its episodic format. Instead, in a lovely convergence of form and content, the troublesome fictional breach between universes has been accompanied by blended narratological structures. Serialized plot lines often come packaged inside a particular, episode-length conflict, and those smaller procedural story lines no longer produce the same infuriating fictional stasis that plagued Fringe during its first season. In fact, Fringe has done a great job of using some of the often-ignored paratextual possibilities of the episodic structure to provide landmarks and signals inside its new multiverse. The show’s opening credits, previously a uniform blue, remain blue when the episode takes place in the show’s original universe, but turn red when the episode takes place Over There. (There’s also a third possibility, which allows episodes that take place in the past to begin with an awesome retro-themed credit sequence). In other words, it’s not just that the new universe changed Fringe from an episodic into a serialized show, but rather, both serialized and episodic elements became far more meaningful inside a multiverse where significant plot events might remain meaningful outside the space of a single episode.

All of which brings me back around to my initial point – that wonderful, weird moment of metadialogue that sparked this whole thing in the first place. At one point during a recent episode, Peter pauses in a serious discussion with Olivia about their troubled romantic relationship (he falls in love with Faux-livia, life gets very complicated) and asks, “does it ever feel like every time we get close to getting the answers, someone changes the question?” It does feel that way, and Peter’s right, of course. The questions have to keep changing, because otherwise, the search for answers would grow tedious, and once every question has an answer, the show has no purpose. But the line is particularly apt because Fringe stopped merely changing the content of the questions, and began to change the nature of the questions as well. It went from, “why does this man have a mechanical heart?” and, “how do we stop this mysterious virus?” to, “who has a stronger ethical code, Walter or Walternate?” and, “which universe deserves to be saved?”

I don’t want to suggest that Fringe is now perfect, or that purely episodic shows are necessarily inferior, or that any struggling scifi show should throw in a parallel universe and cross its fingers. But that line from Peter highlights the thing that’s helped move Fringe from an easily forgettable show into something effective and watchable – the questions change. Maybe it’s because Fringe has been under the threat of near-cancellation from its beginning, or because the voices involved in its production changed, or because it just took a season and a half to figure itself out, but Fringe’s malleability has kept it from succumbing to inertia. As a result, the monsters are scarier, and that moment of metadialogue which elicits such groaning on a show like Grey’s Anatomy, yields a wry smile instead.

_________

Update by Noah: You can read more of Kathryn’s writing at her blog.