“But the picture was not of them, she said. Or, not in his sense. There were other senses, too, in which one might reverence them. By a shadow here and a light there, for instance. Her tribute took that form…”

To the Lighthouse, Virginia Woolf

Those looking for a synopsis and evaluation of Are You My Mother? are directed to a pair of reviews in The New York Times by Katie Roiphe and Dwight Garner, a rare honor for a comic publication. Roiphe is effusive in her praise and suggests that she hasn’t “encountered a book about being an artist, or about the punishing entanglements of mothers and daughters, as engaging, profound or original as this one in a long time.” Her’s is the more detailed and perceptive reading but I am not without sympathy for the conclusions of Garner’s more negative article which suggests an “undistinguished edifice by a builder who forgot to remove the scaffolding.”

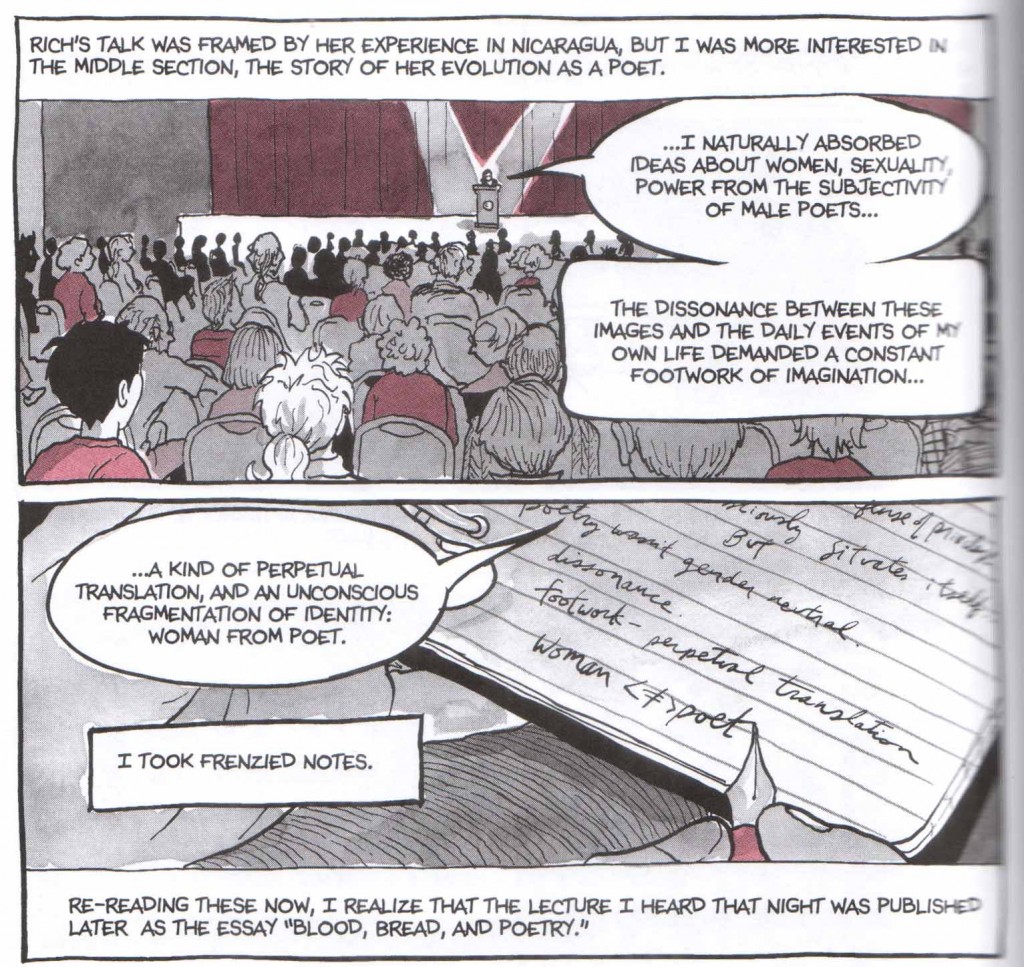

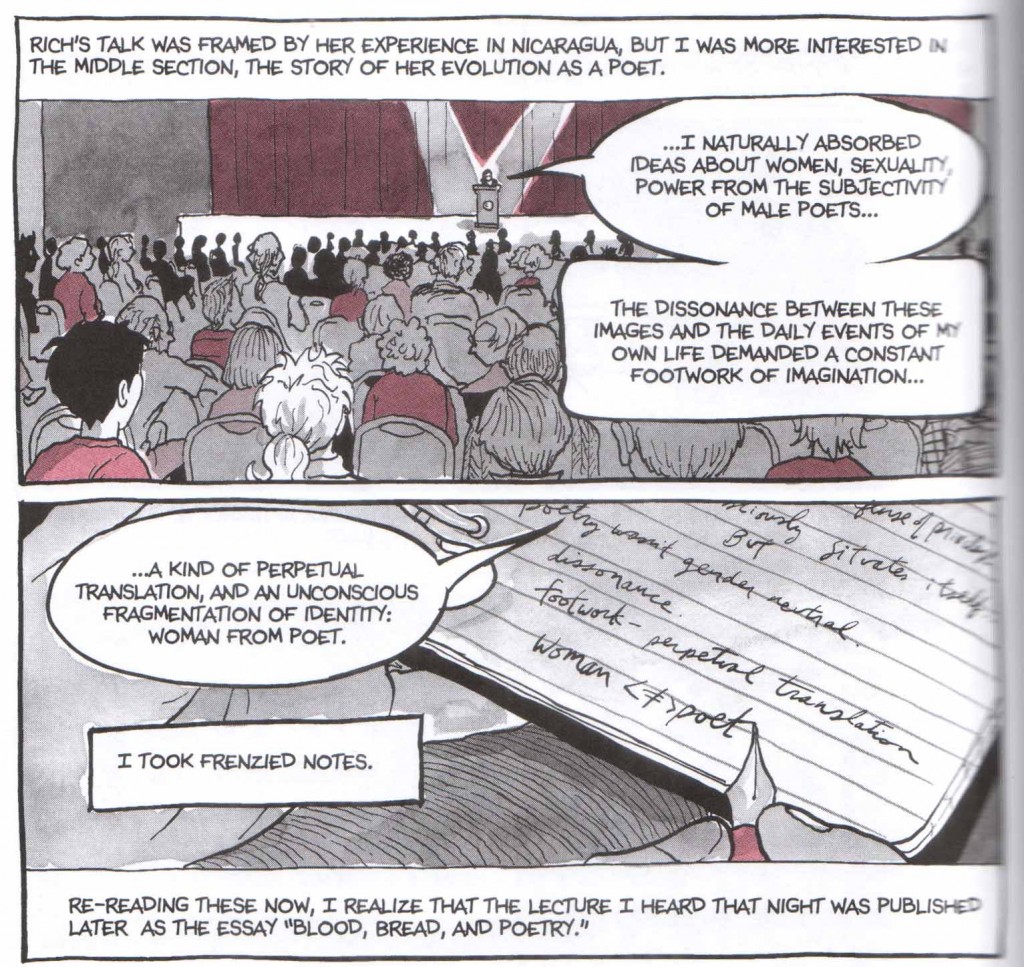

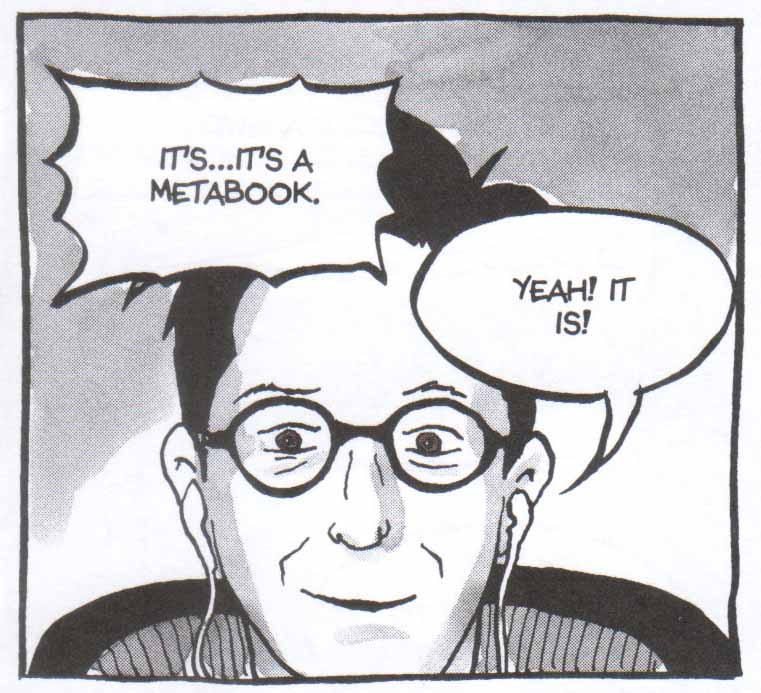

The comic can be easily summarized as an account of Bechdel’s relationship with her mother through the lens of psychoanalysis. There is no avoiding the fact that the comic is immensely didactic and in many ways almost a lecture cum case study of her life and relationships. This is a situation which Bechdel has no intention of avoiding, a point which becomes clear when she cites (approvingly) lectures by Adrienne Rich and Virginia Woolf which were later transformed into notable books (Blood, Bread, and Poetry & A Room of One’s Own). There are sections of this book which will prompt distant memories of the “For Beginners” comics series though Bechdel’s comic is considerably more elevated and complex.

Bechdel prefaces her comic with a quote from Woolf’s To the Lighthouse:

“For nothing was simply one thing.”

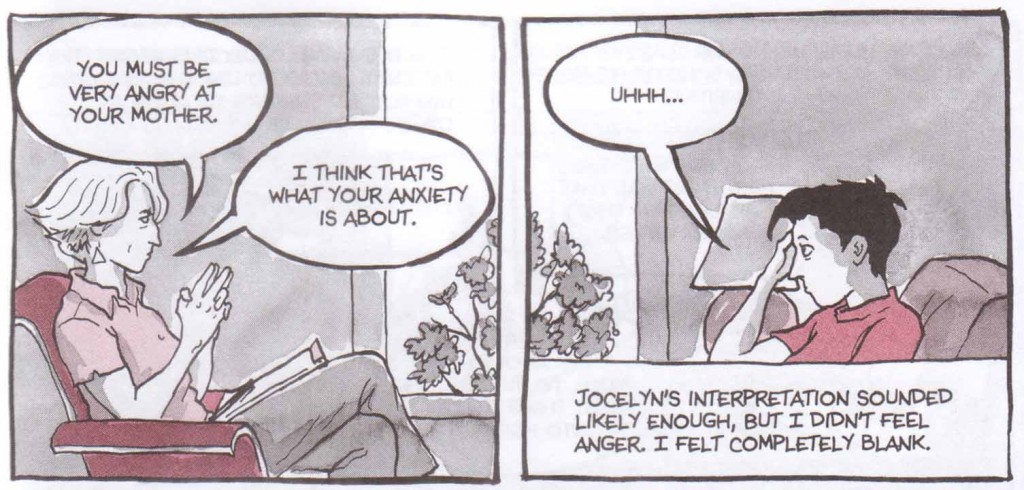

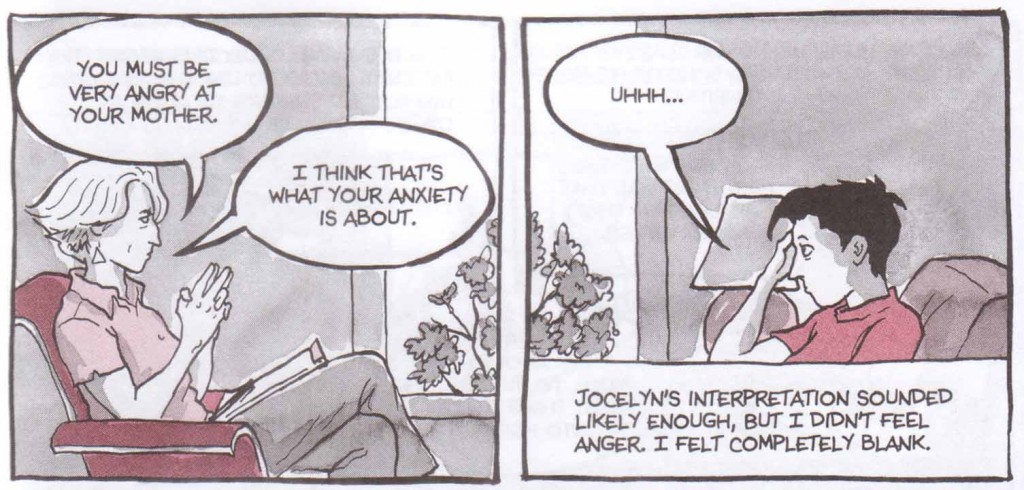

That sentence describes the moment when James Ramsay finally sees that “silvery, misty-looking tower with a yellow eye” for what it is, “stark and straight” and “barred with black and white.” Both images true in their own way just as Bechdel’s overlapping recollections, metaphors, and dreams reveal the shifting facets of her life; the contradictory statements of the Ramsays in that novel (“it will be fine”/”it won’t be fine”) foreshadowing her own work; the same way that the suggestion that she is angry with her mother towards the close of the book is so obvious and yet so impossible to reconcile with the rest of her feelings.

The repeated citations of Woolf and To the Lighthouse invite comparisons between that novel and the comic: the bedtime rituals; the domineering yet strangely dependent father; and (not least) the relationship between the artist, Lily Briscoe and Mrs. Ramsay (Lily’s nascent feminism, her depiction of mother and child as a “purple shadow”, how the focus on marriage in the novel compares with Helen Bechdel’s apparent anxiety about her daughter’s lesbianism etc.). I will set aside these connections for now, but the elements of homage and criticism in the comic are certainly ripe for dissection in some college classroom.

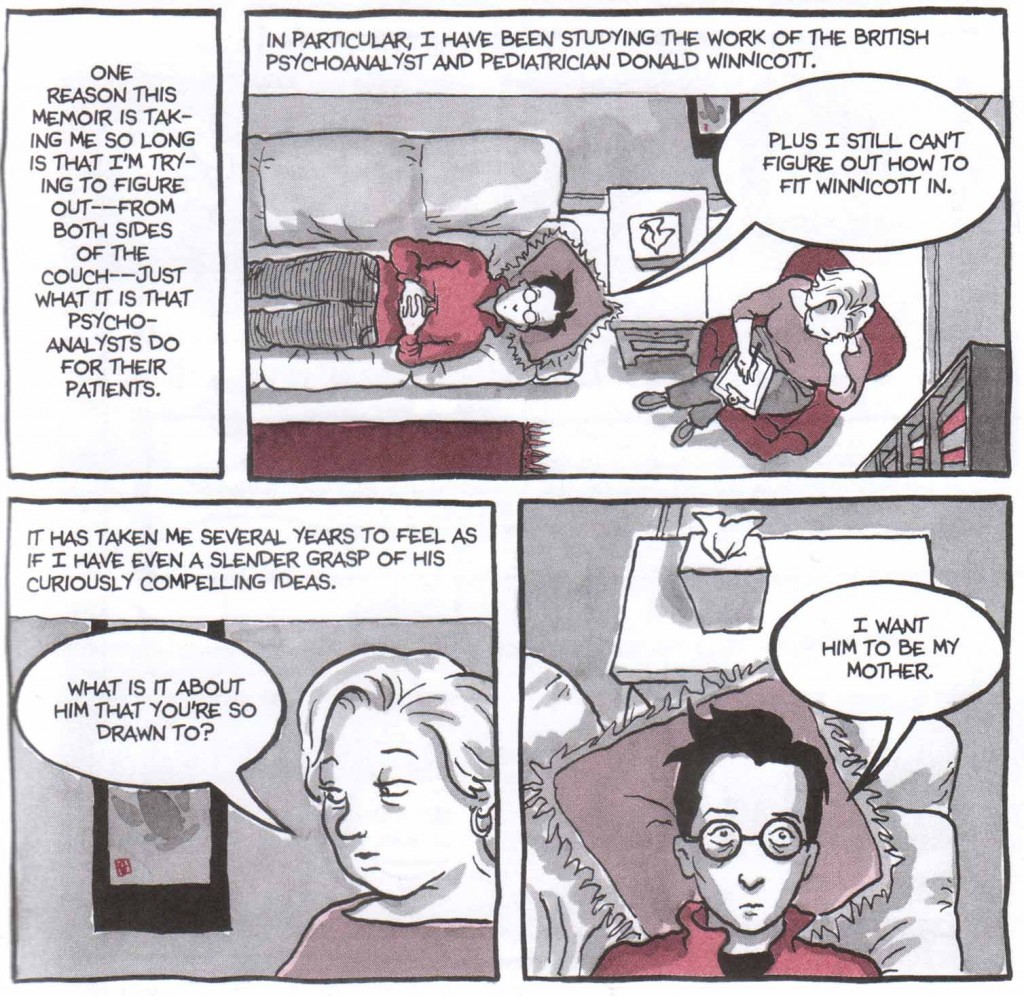

Are You My Mother? follows the structure of dream, analysis, and resolution through chapters titled “The Ordinary Devoted Mother”, “Transitional Objects”, “True and False Self”, “Mind”, “Hate”, “Mirror”, and “The Use of an Object”. Where Fun Home framed its narrative with quotation and criticism of myth and literature, the new comic is heavily centered on the science or pseudo-science (I will assume the former since the author holds it in such high regard) of psychoanalysis. This last dilemma is inconsequential since it is merely the foundation upon which a single life is built, a self-contained world with its own rules, “laws”, and reasons; in many ways an expression of the author’s “therapeutic” creativity and imagination

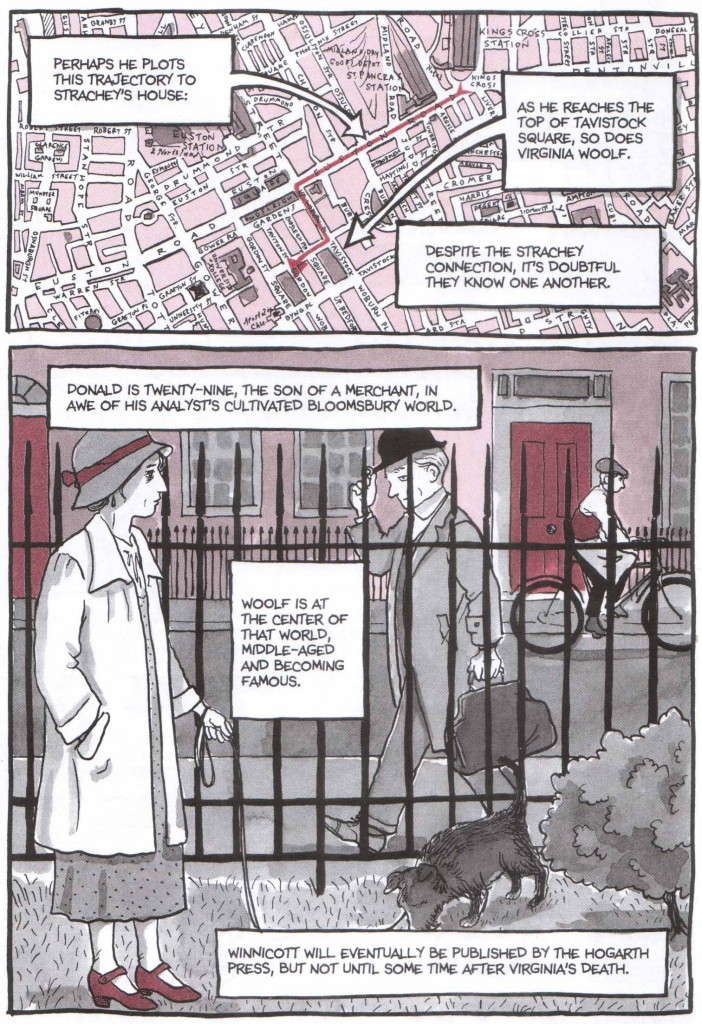

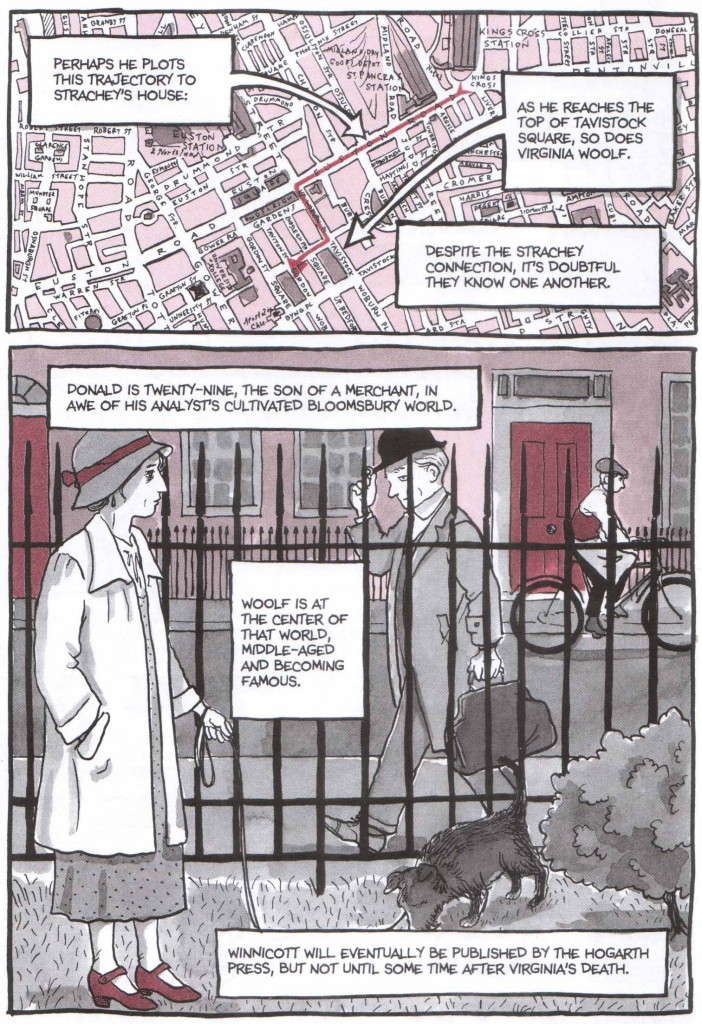

The hardness and scaled down poetry of Are You My Mother? is a subset of this shift in values. The work is highly expository and Bechdel spends considerable time and effort explaining psychoanalytic and developmental concepts and their application in her life. Even so, Bechdel does leave many things unsaid—some obvious, others less so. The early account of a stroll through London by Virginia Woolf and Donald Winnicott (the paths adjacent but never actually meeting) is ostensibly historical fiction but is clearly a metaphor for the conjunction and distance separating the literary memoir (the Bloomsbury group, the Hogarth press, and hence Woolf and her diaries) and science, connecting the main root of psychoanalysis to the personal analysis she wants to concentrate on.

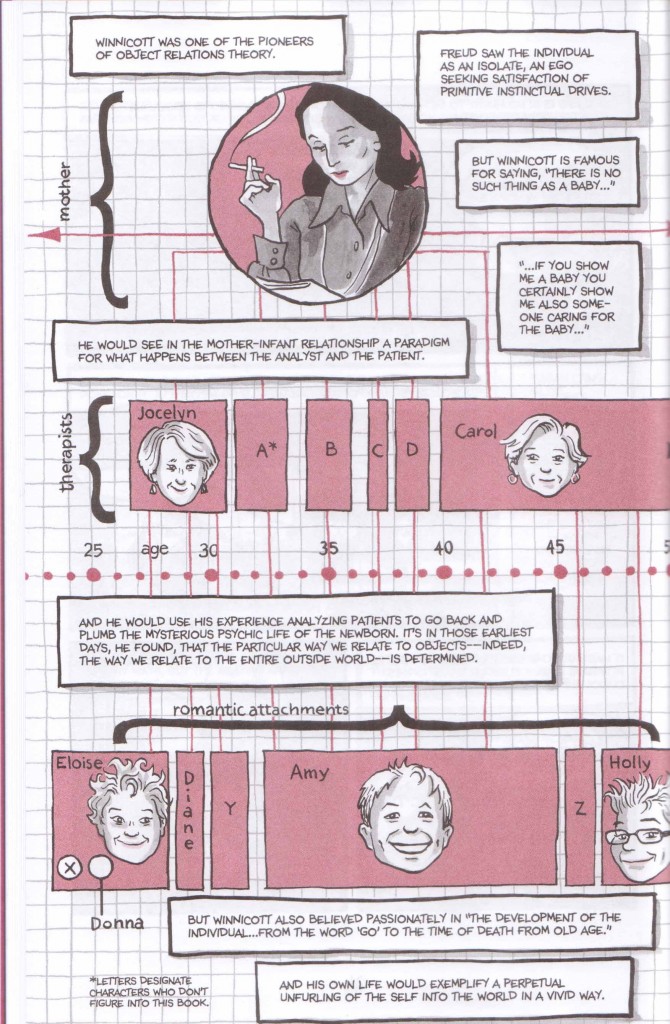

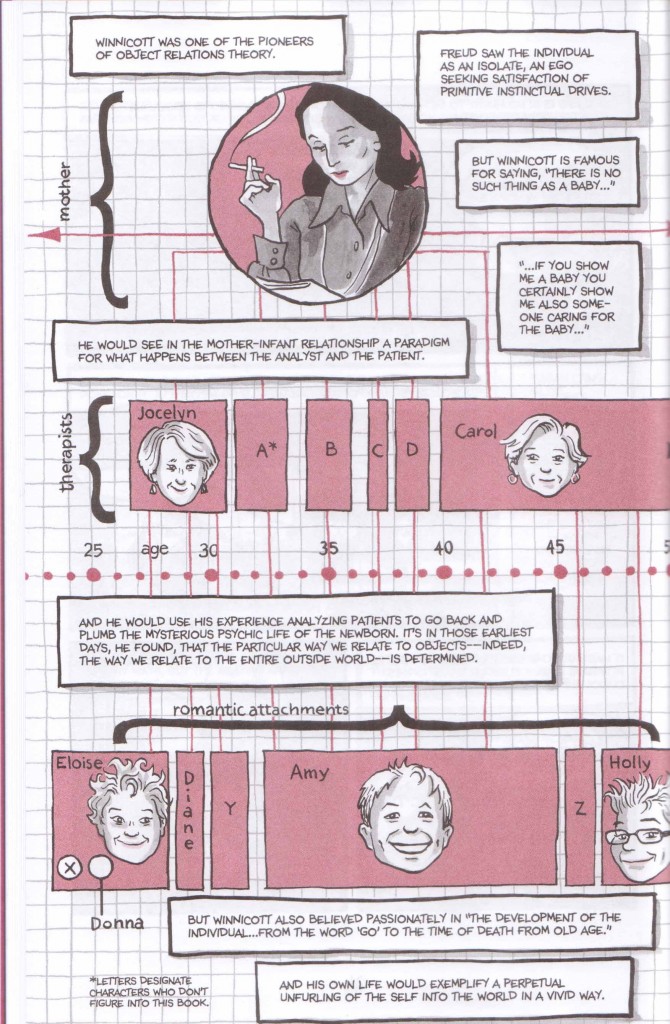

The therapeutic and relationship diagram seen on page 22 is the true index of Bechdel’s comic which readers will need to refer to at various points in the narrative if only to keep track of the discontinuities and overlap of years. The timeline suggests a kind of mathematical equation even though it exists purely in the realm of the graphic arts with all its approximations. Those looking for a linear account of these relationships will be disappointed for the progress and conclusions are as disjointed as any patient led analysis. It is very much a Holmesian mystery (hence its “comic drama” subtitle) offering the pleasures of a hunt which the author—who at this point has been in therapy longer than she has not—so enjoys.

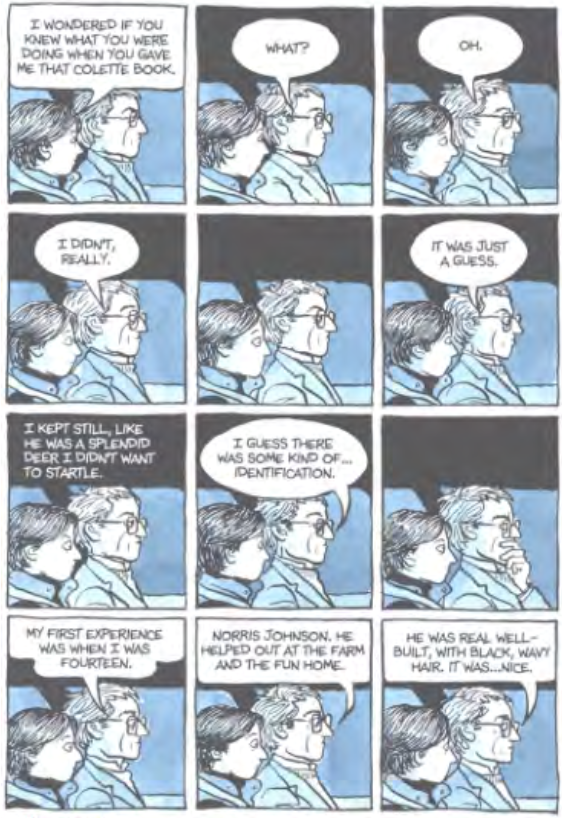

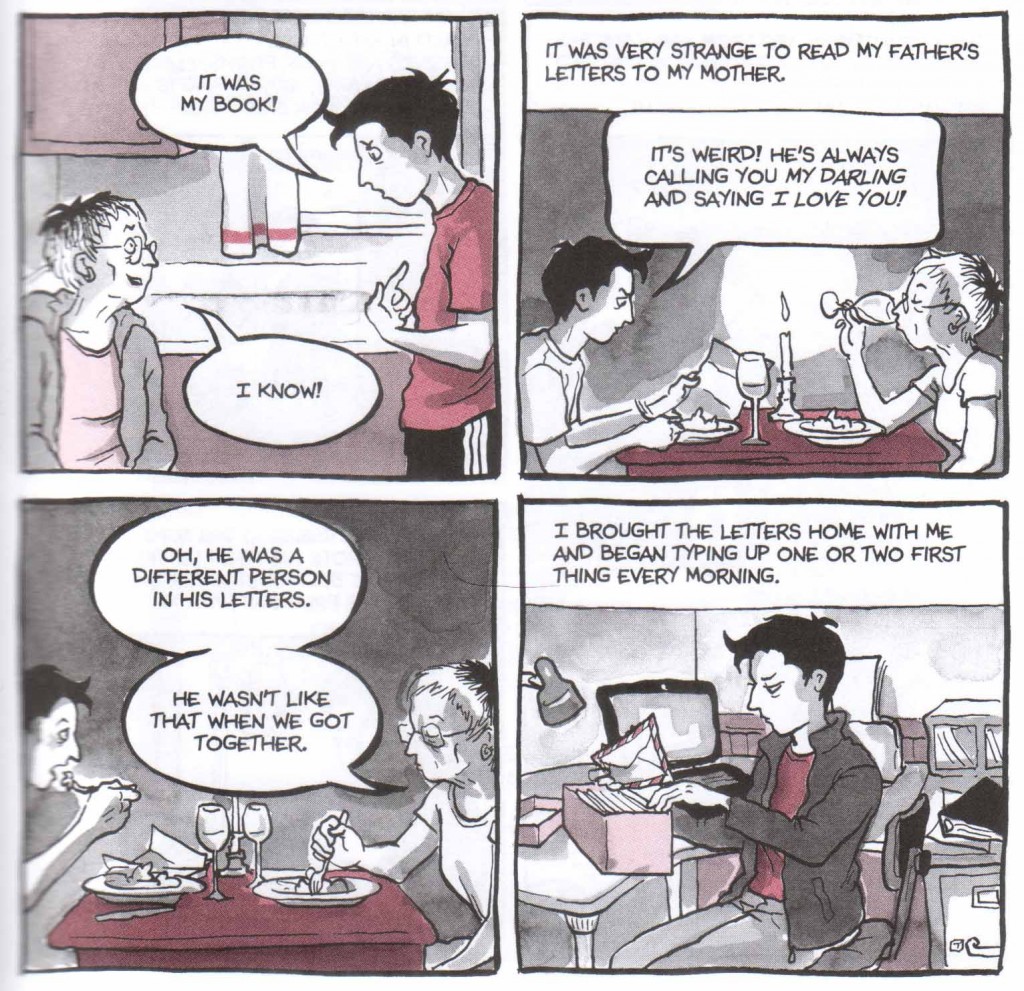

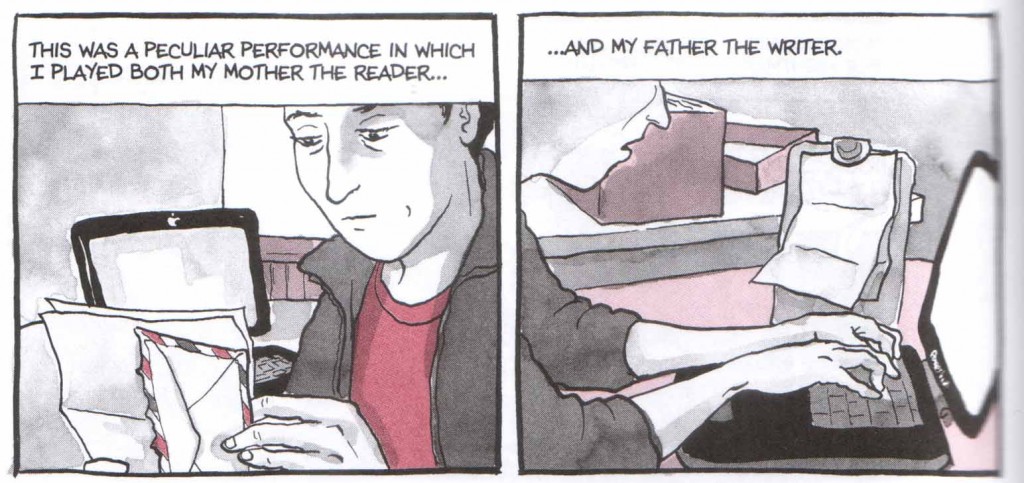

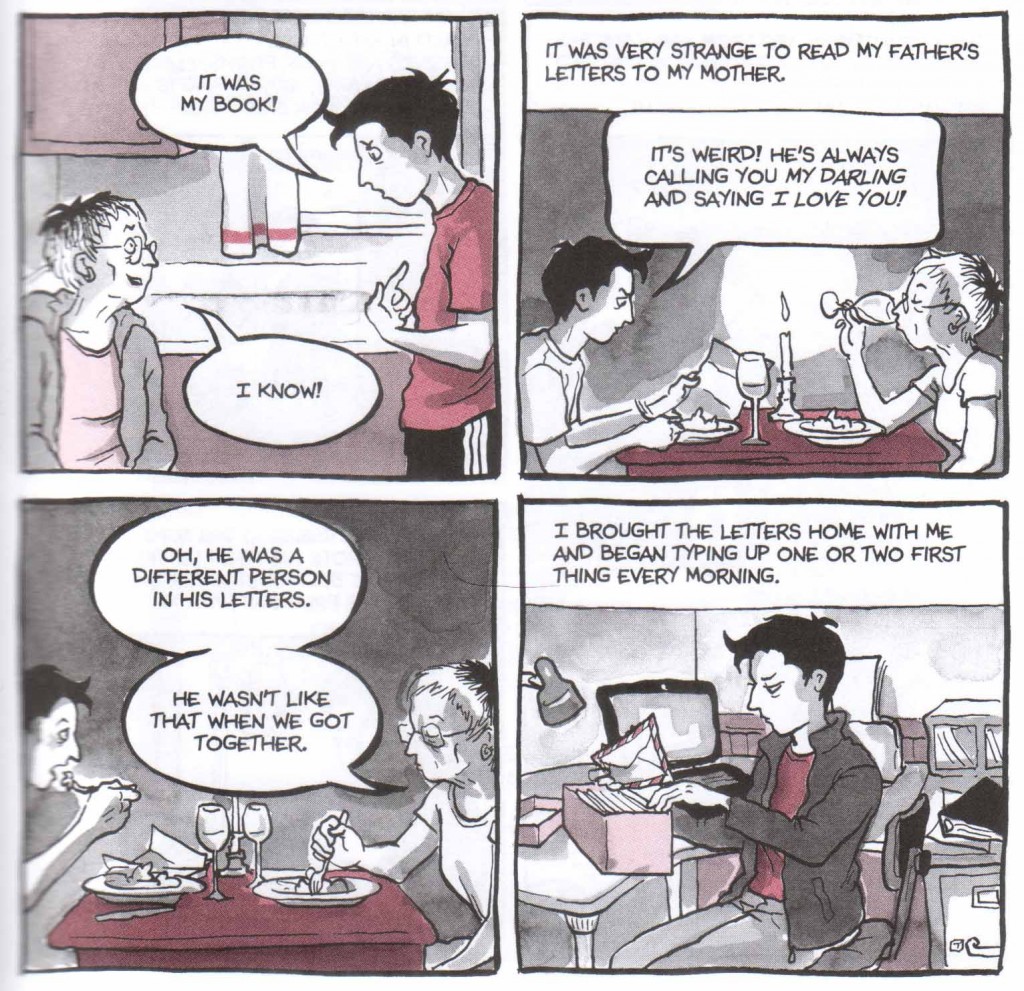

Fun Home was rife with text-image counterpoint and juxtaposition and while these still exist in abundance in Bechdel’s latest comic, the focus has shifted into overlapping texts which “speak” all at once creating a kind of lexical broth, not only creating a tension between texts but also a conflict between the written and the spoken word

—the romantic language of her father’s letters to her mother contrasting with her mother’s impression decades later that, “[He] was a different person in his letters. He wasn’t like that when we got together.” Not simply a comment on truth but the entire project she has placed before us, for we see her on the very next page in “a peculiar performance” in which she plays both her “mother the reader” and her “father the writer.”

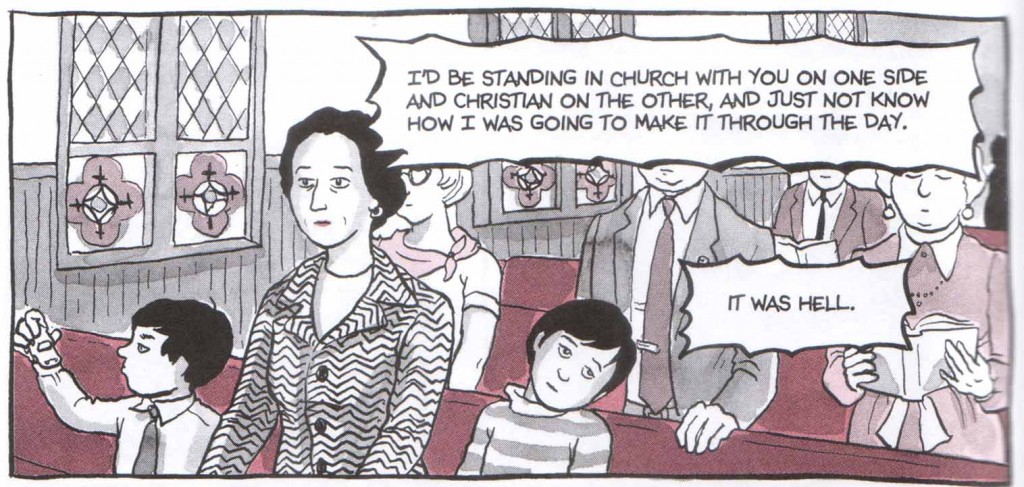

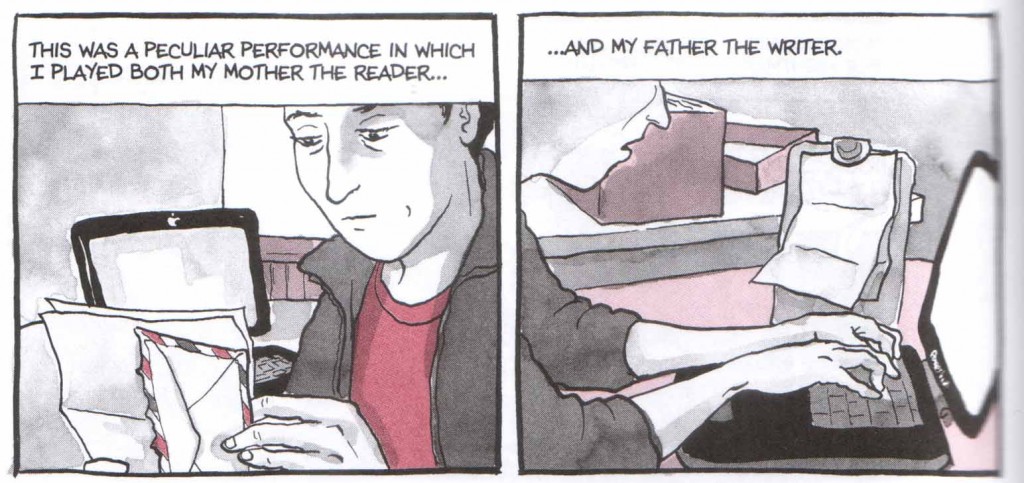

Even with this proviso in mind, I would still suggest that where the former memoir offered possibilities and guess work concerning her father’s sexuality and suicide, this new work advances diagnoses and cures; a move away from the intemperance of the confessional booth and religion to rationality, that sacrament providing no escape for Bechdel’s mother whose depression was only accentuated by her presence at church (“It was hell.”).

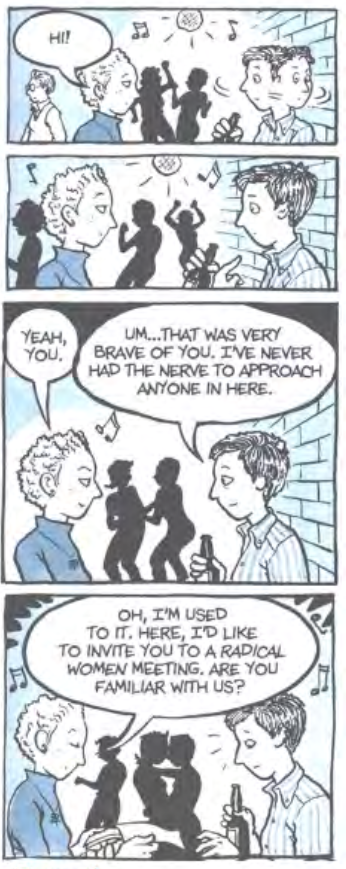

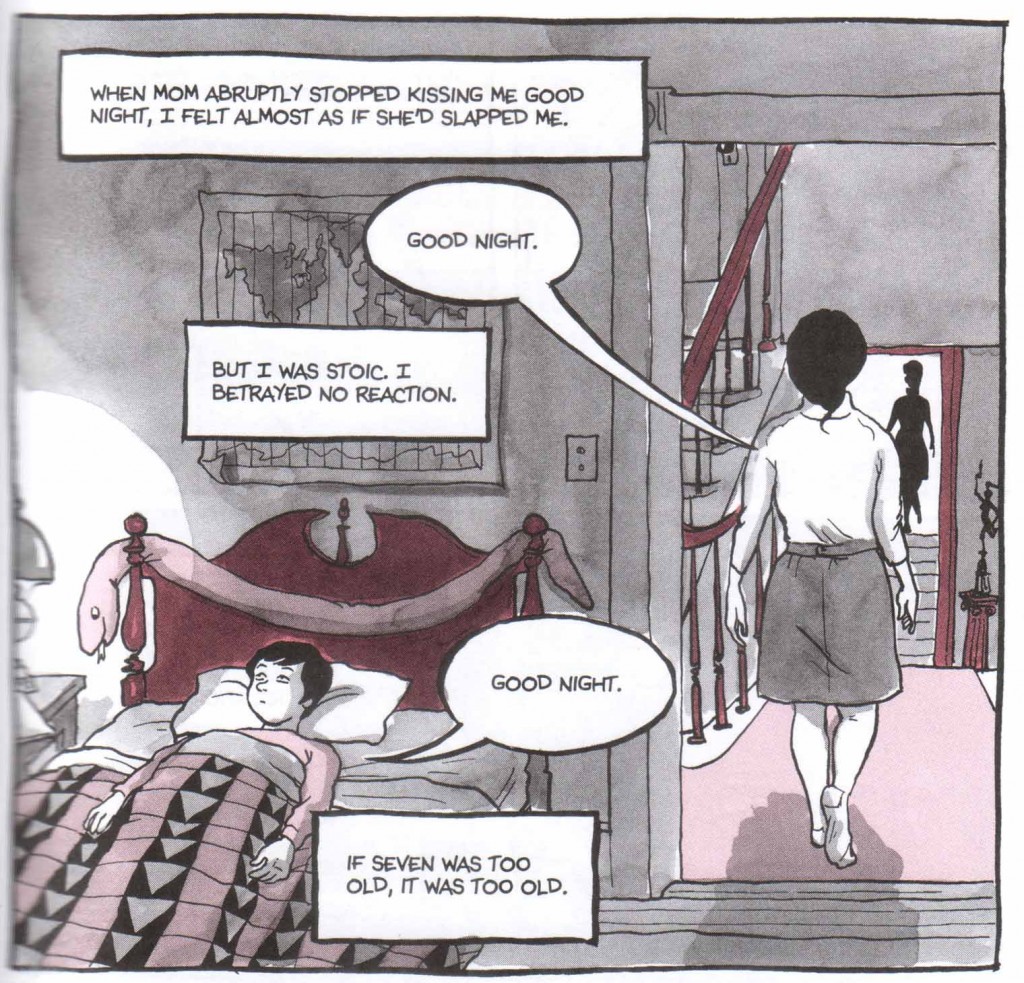

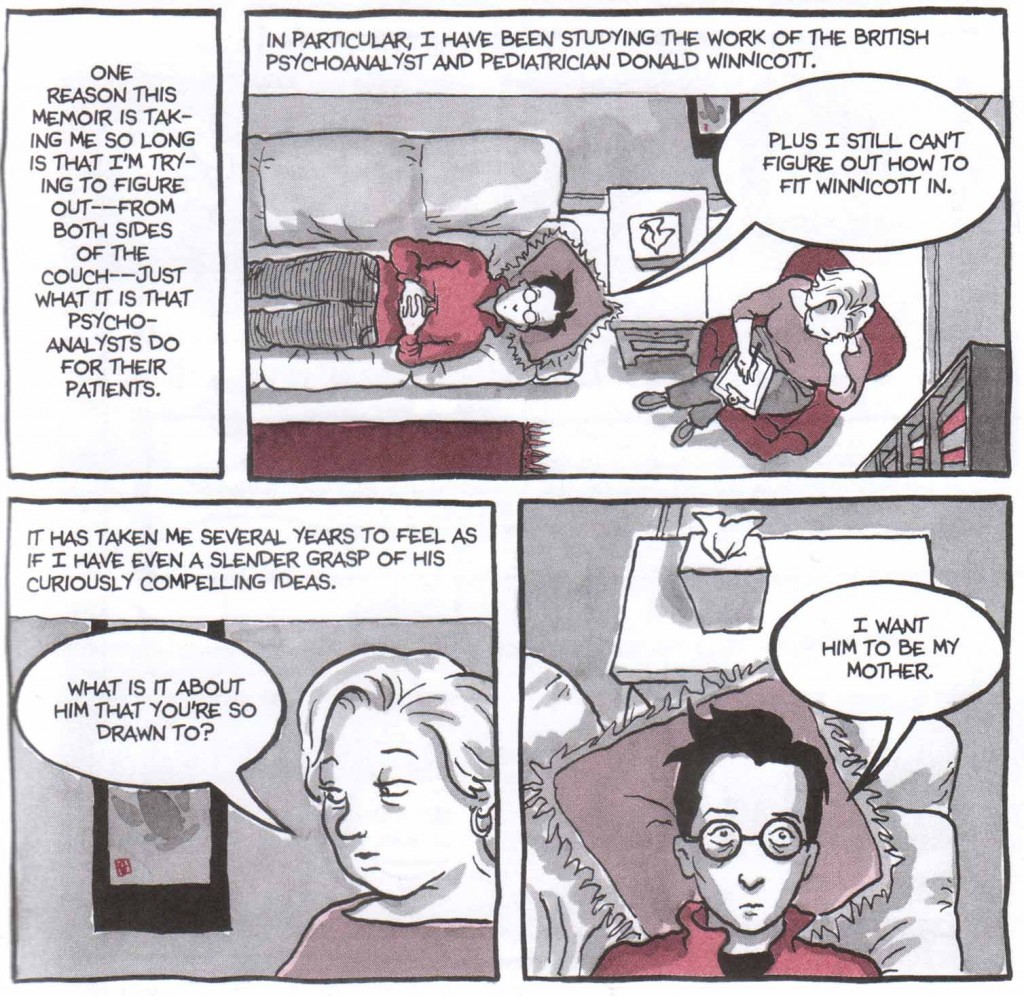

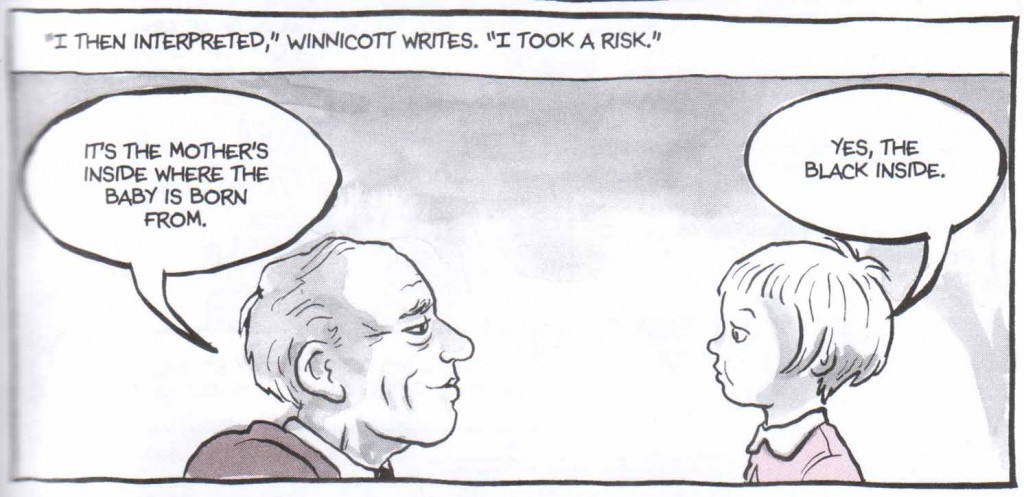

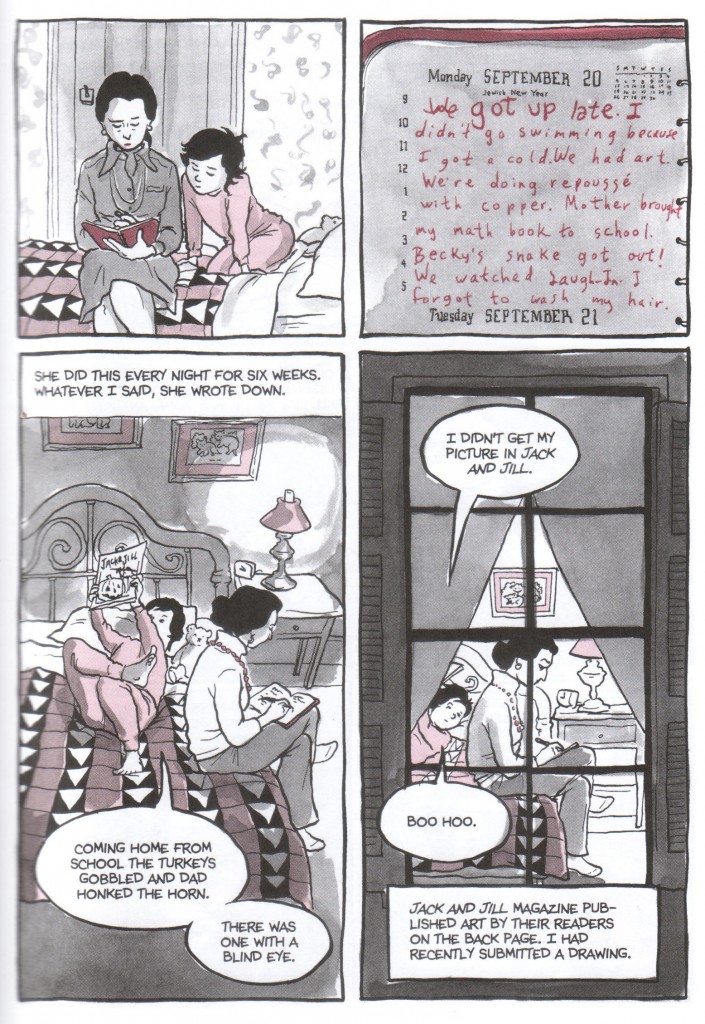

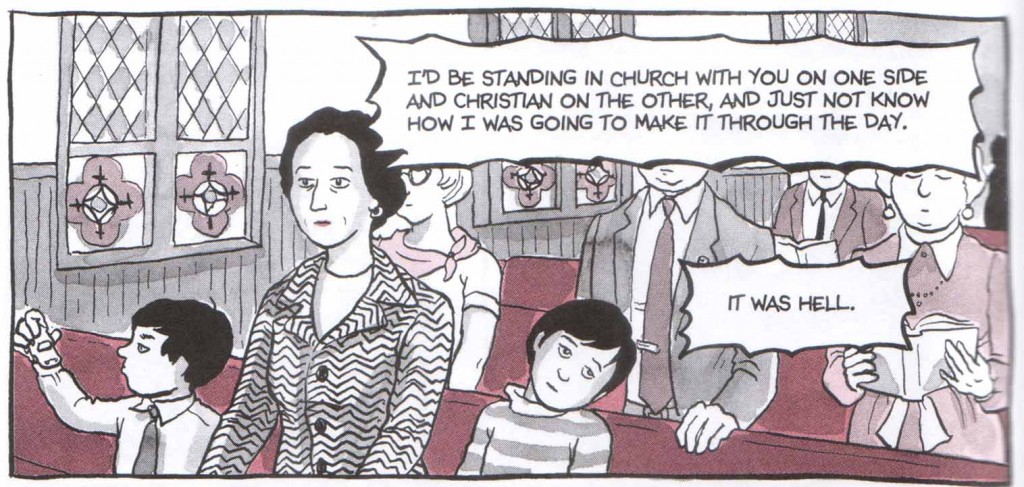

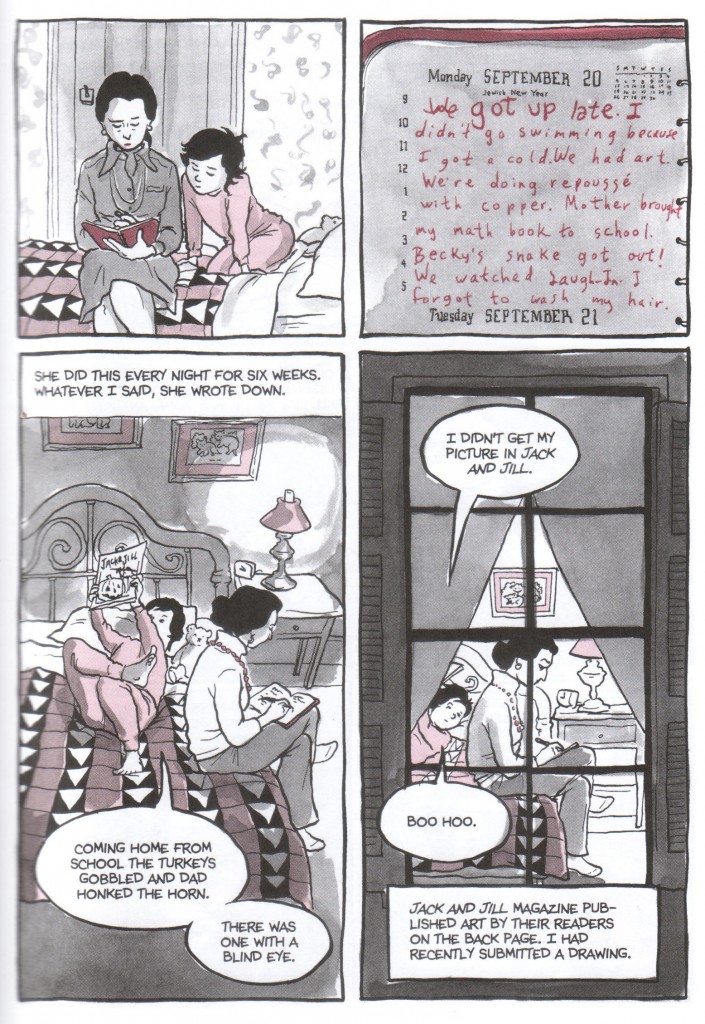

Hidden in the title is a threefold question. The most obvious one relates to the uncovering of her mother’s aspirations and depression, that sense of abandonment when she stops kissing her at the age of seven and seems to prefer her male offspring. This tension is reiterated throughout the comic both directly (in the pre-college tiff between mother and daughter) and indirectly (in Donald Winnicott’s “Oedipal revolt” against his psychoanalytic mother”, Melanie Klein). Bechdel’s long one-way conversations (interview, interrogation, analysis) over the phone with her mother are always initiated by herself and she begins to surreptitiously take notes like an analyst dissecting her mother’s psyche.

The second question manifests itself in the transference which Bechdel casually mentions and then elaborates upon in chapter 3. The most overt instance of this is the dream sequence at the start of that chapter which shows her analyst in the guise of her mother, mending her clothes and thus symbolically her tears. Later Bechdel pulls out a pad to note down her therapist’s suggestion following a breakthrough, thus mirroring her activities during her telephone conversations with her birth mother.

Her therapists by proxy are also ever present in the text, and she makes the transference explicit in a statement regarding Donald Winnicott (“I want him to be my mother.”)

While some of the conclusions Bechdel reaches with her therapists may seem trite, the solace she gains from their words of affirmation (“I like you.”) are more disturbing [1].

The third question is directed at her readers for there is little doubt that Bechdel is taking the talking cure with her readers in a one-sided conversation. The memoir as a means of catharsis is of course repugnant to some but Bechdel clearly thinks otherwise and cites To the Lighthouse as an instance of one such (temporary?) success. One presumes that she expects them to report back with their findings and in a sense they already have. Perhaps, the ultimate expression of this relationship would be an analysis of her self-analysis. Bechdel never fails to emphasize her dependence on this tenebrous and fickle approval, a chimeric cycle of ambition and reinforcement which the author seems to think is (in part) healthy though painful—like a neurotic child throwing a tantrum.

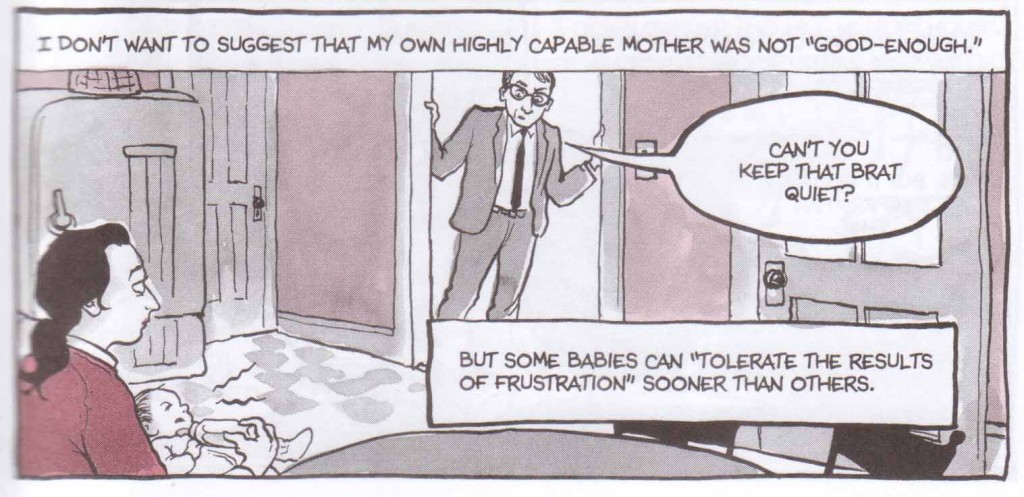

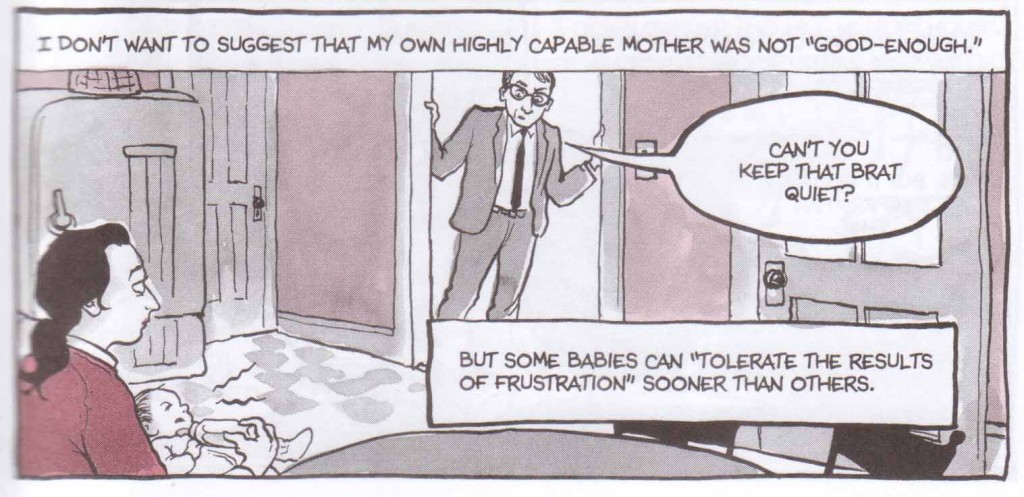

The title of Bechdel’s comic recalls, of course, P. D. Eastman’s children’s book of the same name, the cheerful tale of a baby bird’s search for its mother and its failure to imprint. Bechdel does very much the same throughout her memoir with interspersed anecdotes on her mother’s failure to breast feed her as a child. On at least four occasions, she shows her father disrupting the bond between mother and child. Hence the aforementioned confusion of progenitors.

These developmental disruptions are rationalized through the work of Winnicott and Alice Miller. Yet they also place her firmly in the position of a child in relation to her interlocutors, this despite her full grown size for most of the comic. The only other prominent psychoanalytic text in Bechdel’s book is Sigmund Freud’s The Interpretation of Dreams. This emphasis can be easily explained by a statement found in the opening pages of Miller’s The Drama of the Gifted Child which suggests that:

“…every childhood’s conflictual experiences remain hidden and locked in darkness, and the key to our understanding of the life that follows is hidden away with them.”

In the same chapter, we find some “basic assumptions” concerning a child’s need for a “legitimate” and “healthy narcissism”. Miller states that “parents” (and presumably individuals in general):

“…who [do] not experience this climate as children are themselves narcissistically deprived; throughout their lives they are looking for what their own parents could not give them at the correct time—the presence of a person who is completely aware of them and takes them seriously, who admires and follows them. This search of course, can never succeed fully since it relates to a situation that belongs irrevocably to the past, namely to the time when the self was first being formed.” [emphasis mine]

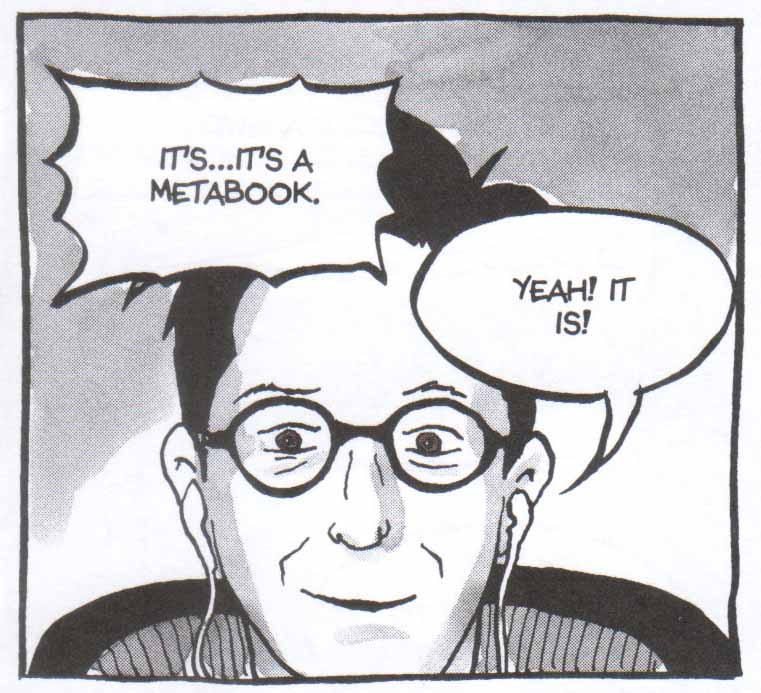

Bechdel provides herself as a frank and unhesitating example of this formulation at every stage in her book. One might say that even the metatextural moments in the comic are a subset of this condition, the “scaffolding” left out for all to see in the interest of full awareness.

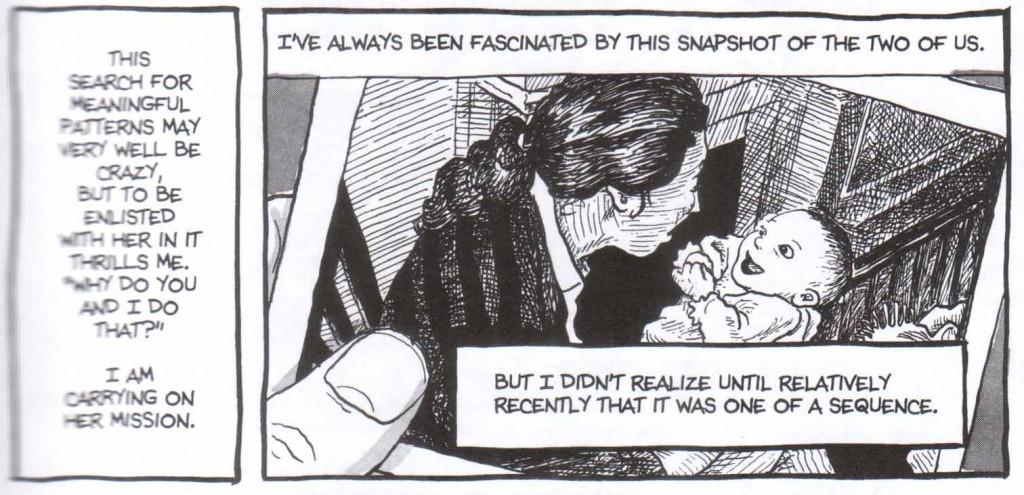

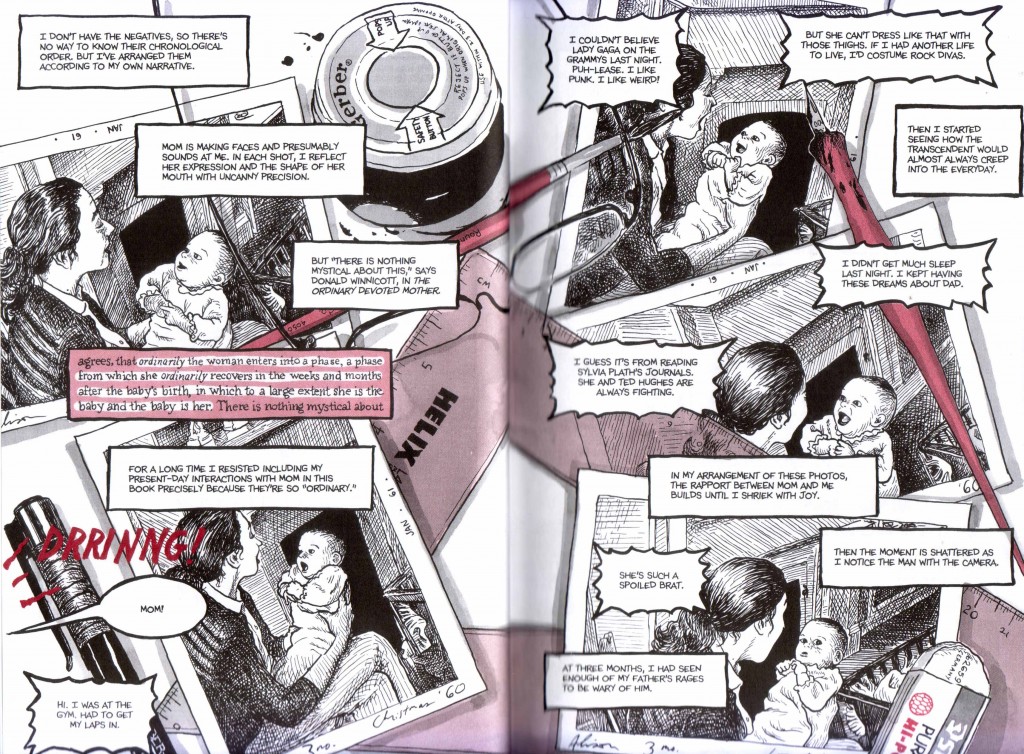

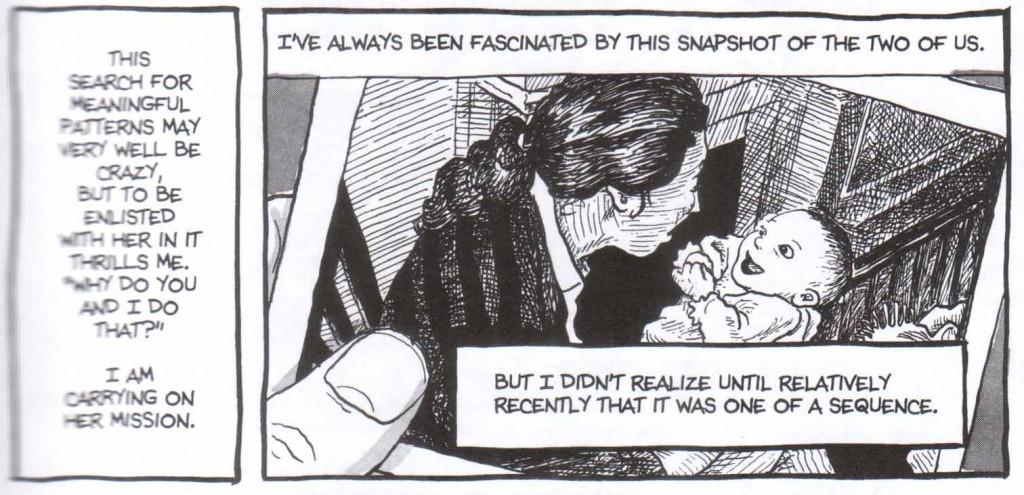

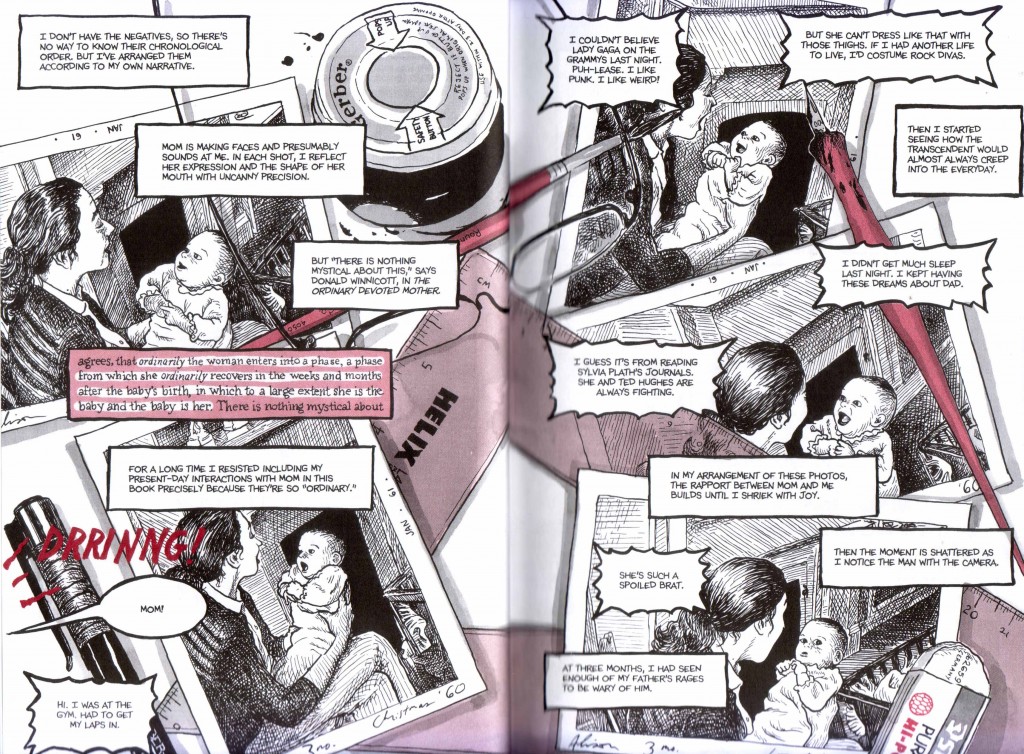

Of these moments, some are patent while others are hinted at. The two page spread (pg 32-33) showing her discovery of a set of baby photos is an example of the latter. The table top is shown littered with the detritus of creation and falsity, the images presumably photo-referenced but still at least a step removed from the originals, just as Bechdel’s comic will always remain a land of half-truths and potential “lies of omission”, of fiction and autobiography. The section in question is preceded by an earlier panel:

“I’ve always been fascinated by this snapshot of the two of us. But I didn’t realize until relatively recently that it was one of a sequence.”

And later,

“I don’t have the negatives, so there’s no way to know their chronological order but I’ve arranged them according to my own narrative.”

This pair of pages can be seen as a simple analysis of a moment in time but also of the comic as a whole, the chapters of which are easily disgorged and rearranged to suit the moment and desired meaning. Is there any reason, for example, why that final image in Bechdel’s sequence should not be placed first? Bechdel’s arrangement sees her mother as helpless before her father’s misanthropy; the alternative suggests a more successful comforter and protector.

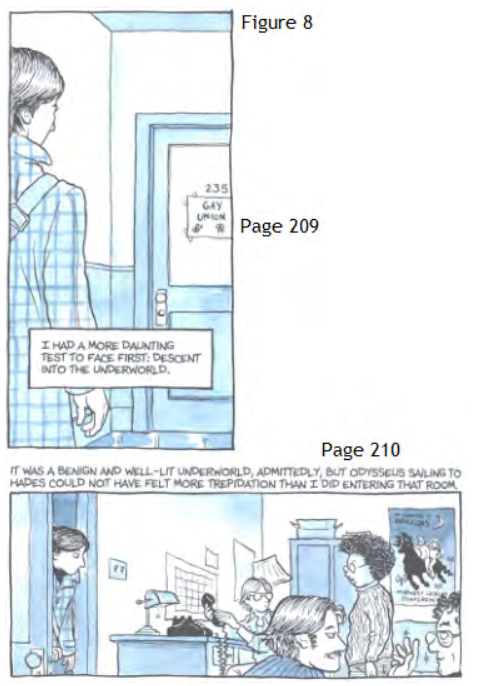

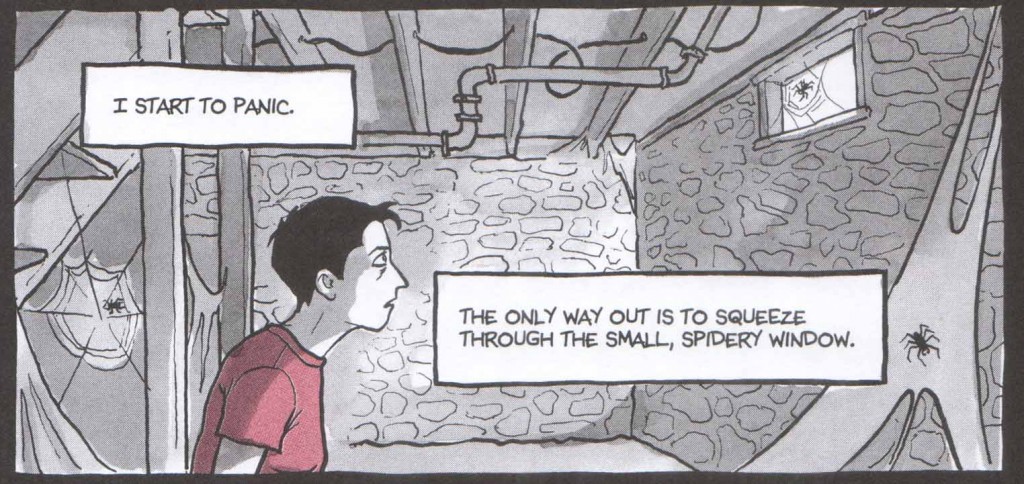

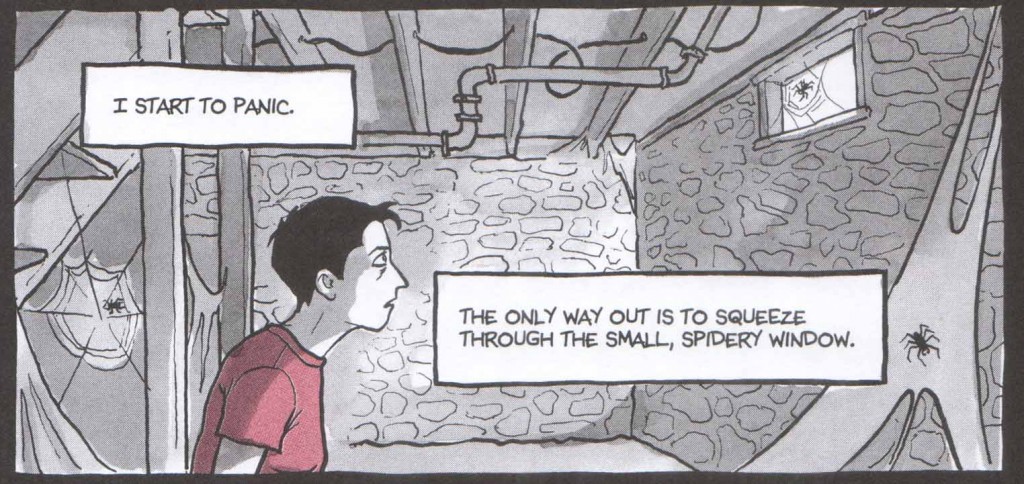

Analyzing every facet of Are You My Mother? would be an exhausting process both for me and any potential readers. Bechdel’s traditional approach to drawing and cartooning obscures an obsessive approach to structure and recurrence in her narrative, making it one of the densest comics reading experiences of the past few years. On the most basic level, this amounts to linear exposition though sometimes separated by the entire breath of the book. For instance, on the very first page of the comic, Bechdel recounts a dream in which she is trapped in a dank cellar, the only way out being a “small, spidery window” which she forsakes upon the sudden materialization of a door.

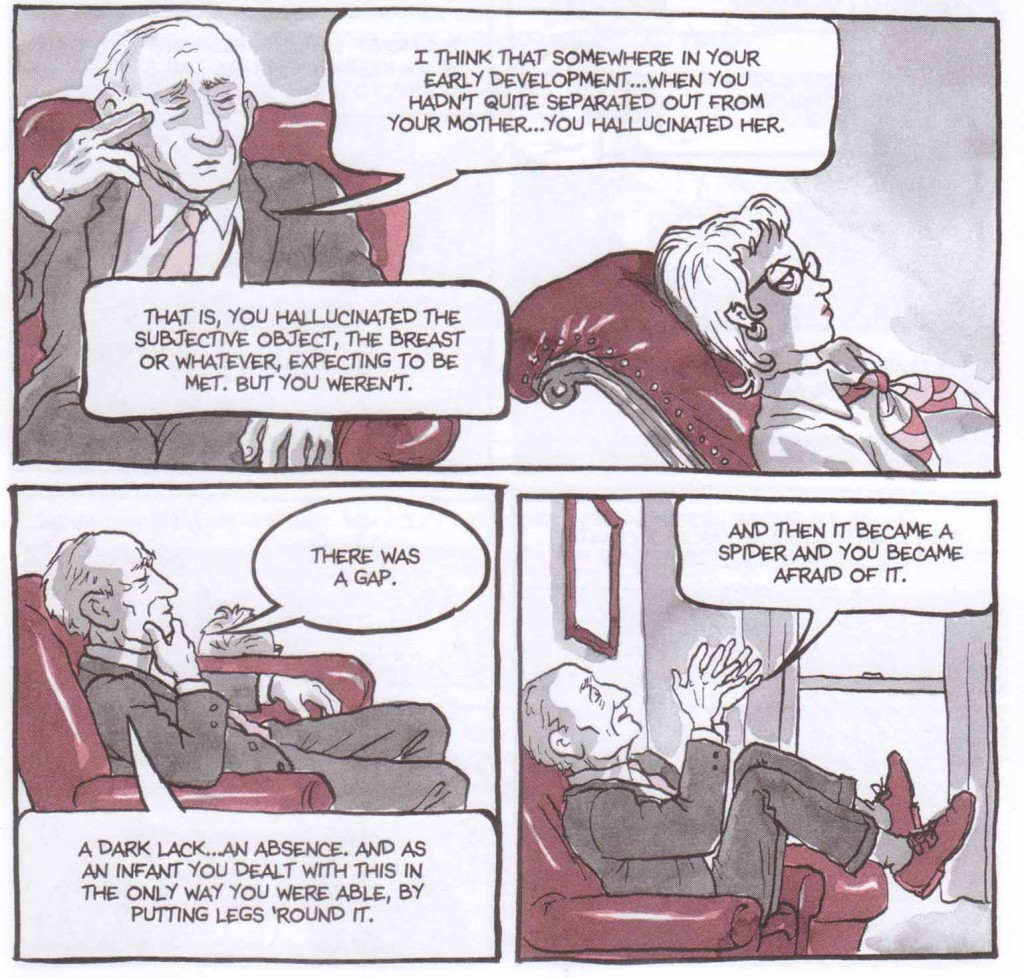

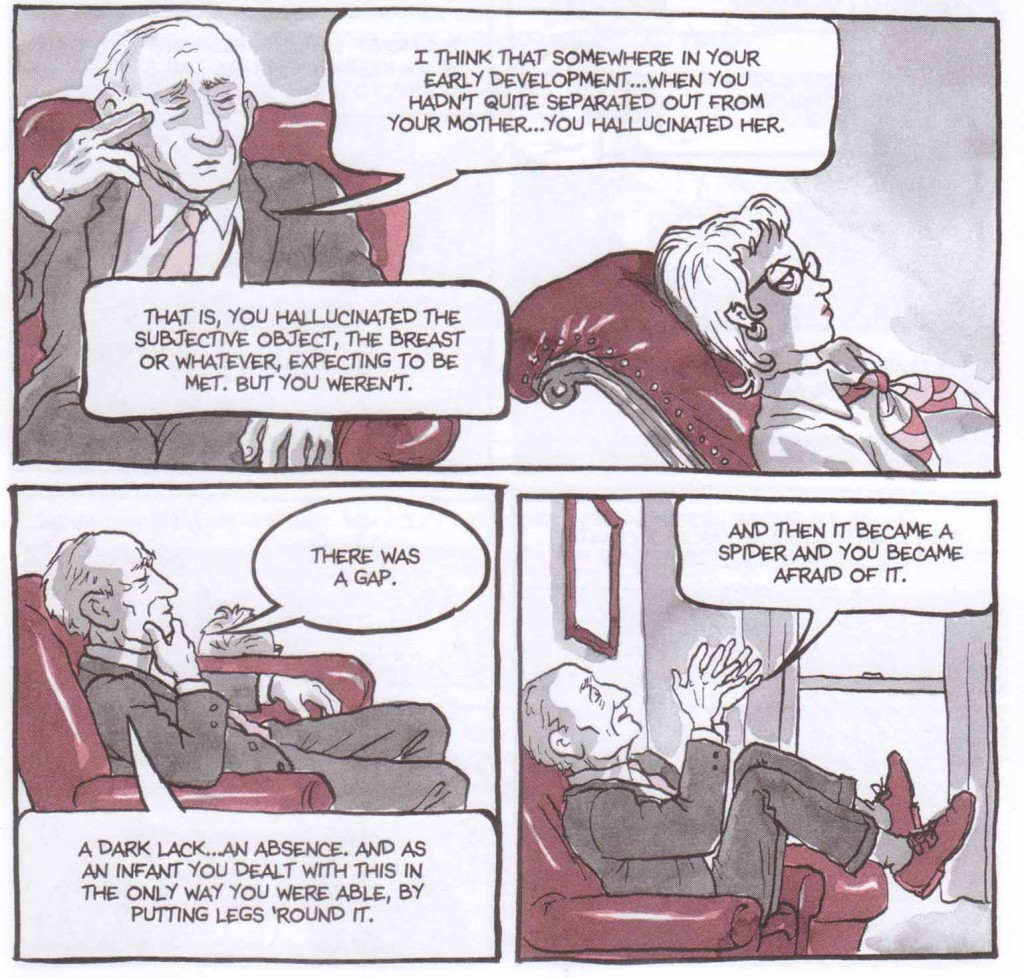

Her first sentence upon falling back to reality is, “Mom.” The spider’s web appears again in a dream initiating the second chapter of the book. Nearly 300 pages later towards the close of the comic, we learn of her mother’s arachnophobia which was triggered by the sight of seeing a grasshopper being entombed in silk as a child. Then a chance reading of a biography of Winnicott reveals his analysis of an arachnophobic patient in his twilight years:

“I think that somewhere in your early development…when you hadn’t quite separated out from your mother…you hallucinated her. That is, you hallucinated the subjective object, the breast or whatever, expecting to be met. But you weren’t. There was a gap…And then it became a spider and you became afraid of it.”

This analysis and its accompanying forebodings suggest that both Alison and Helen Bechdel are caught in a vicious cycle of narcissistic deprivation, the end result of which is described by Miller:

“…a person with this unsatisfied and unconscious (because repressed) need is compelled to attempt its gratification through substitute means. The most appropriate objects for gratification are a parent’s own children.”

And later,

“…she [the mother] then cathects him narcissistically. This does not rule strong affection. On the contrary, the mother often loves her child as her self-object, passionately but not in the way he needs to be loved. Therefore, the continuity and constancy…are missing…from this love. Yet what is missing above all is the framework within which the child could experience his feelings and his emotions. Instead, he develops something the mother needs…but it nevertheless may prevent him, throughout his life, from being himself.”

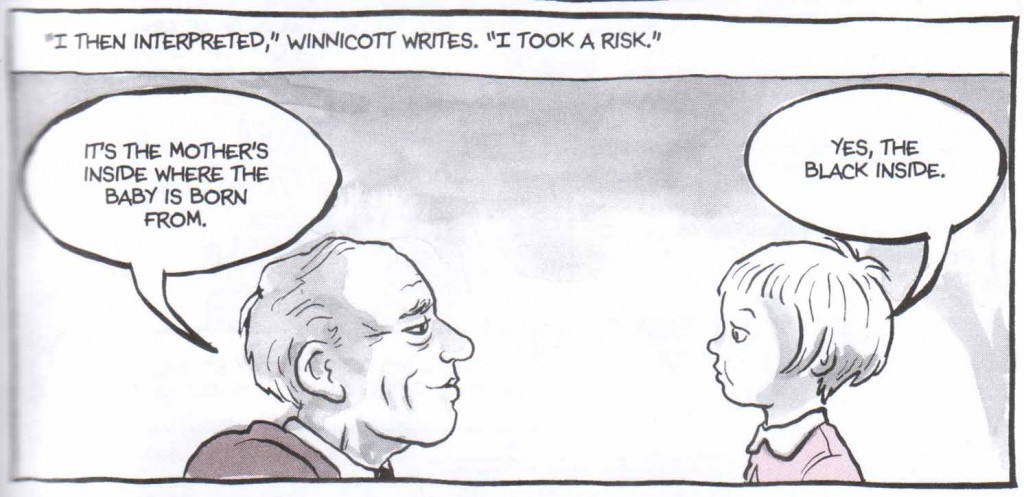

On the next page, Winnicott’s final moments are revealed; the date, one month before Bechdel started keeping her diary. In that diary, a single episode is highlighted, a case of food poisoning with the vomitus taking on the shape of a spider, the “dark lack” and “absence” which Winnicott was just remarking upon just a page before. And thus it continues with Bechdel layering image over image and word over word.

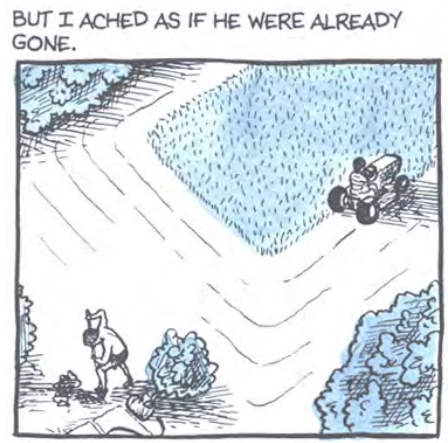

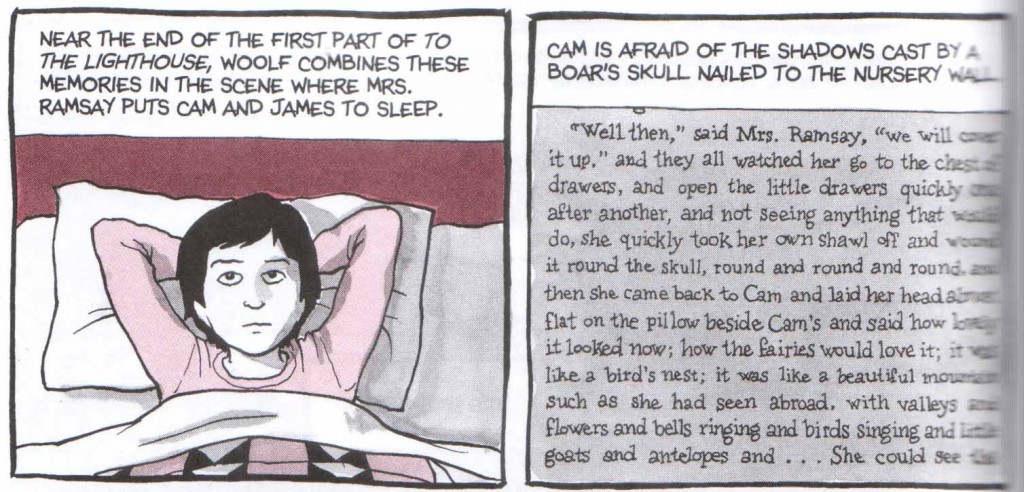

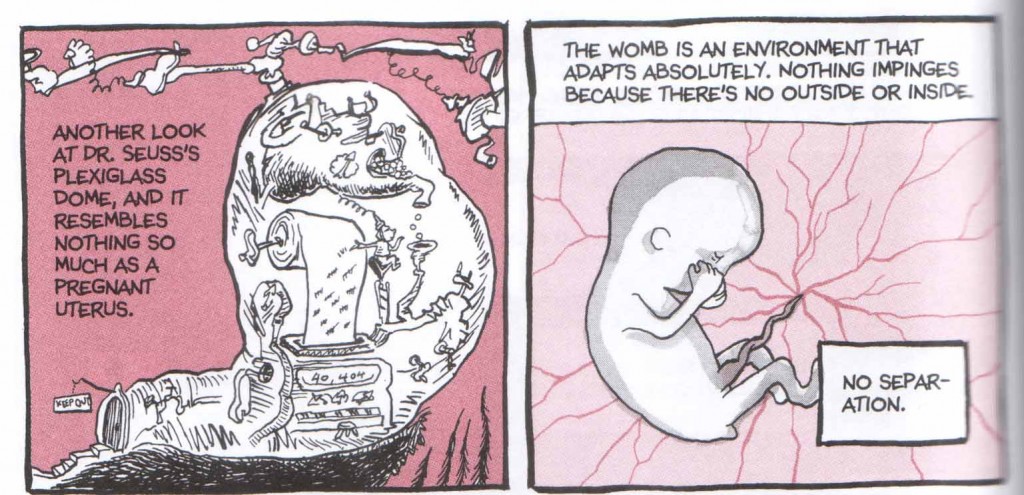

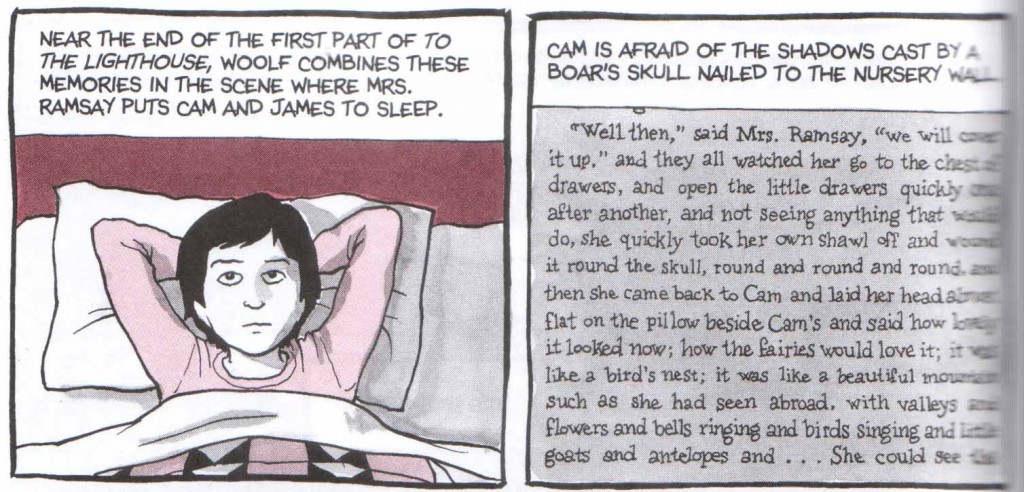

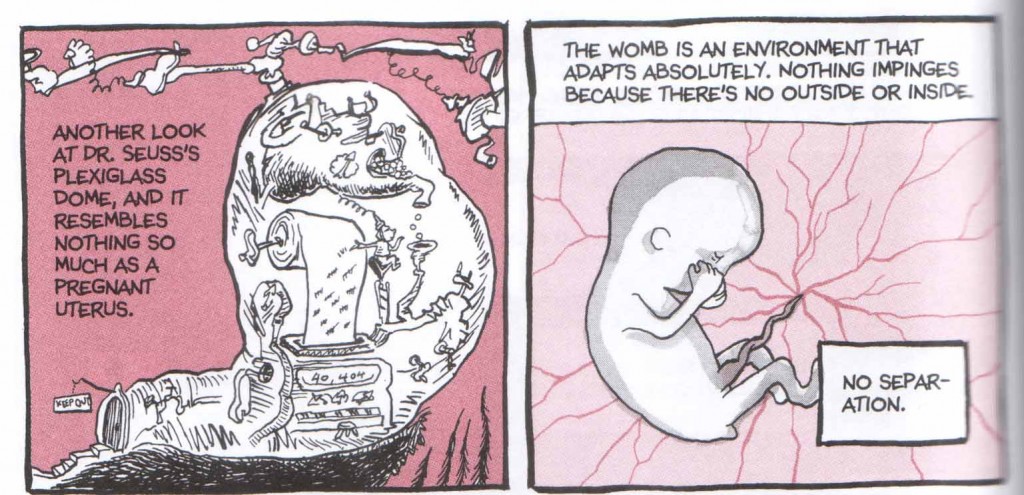

The chapter, “Mind”, is another case in point, with its repeated references to birth, death, and the womb. Woolf, in transforming an episode from her childhood into a scene from To The Lighthouse where a boar’s skull is covered with a shawl, is Bechdel’s exemplar.

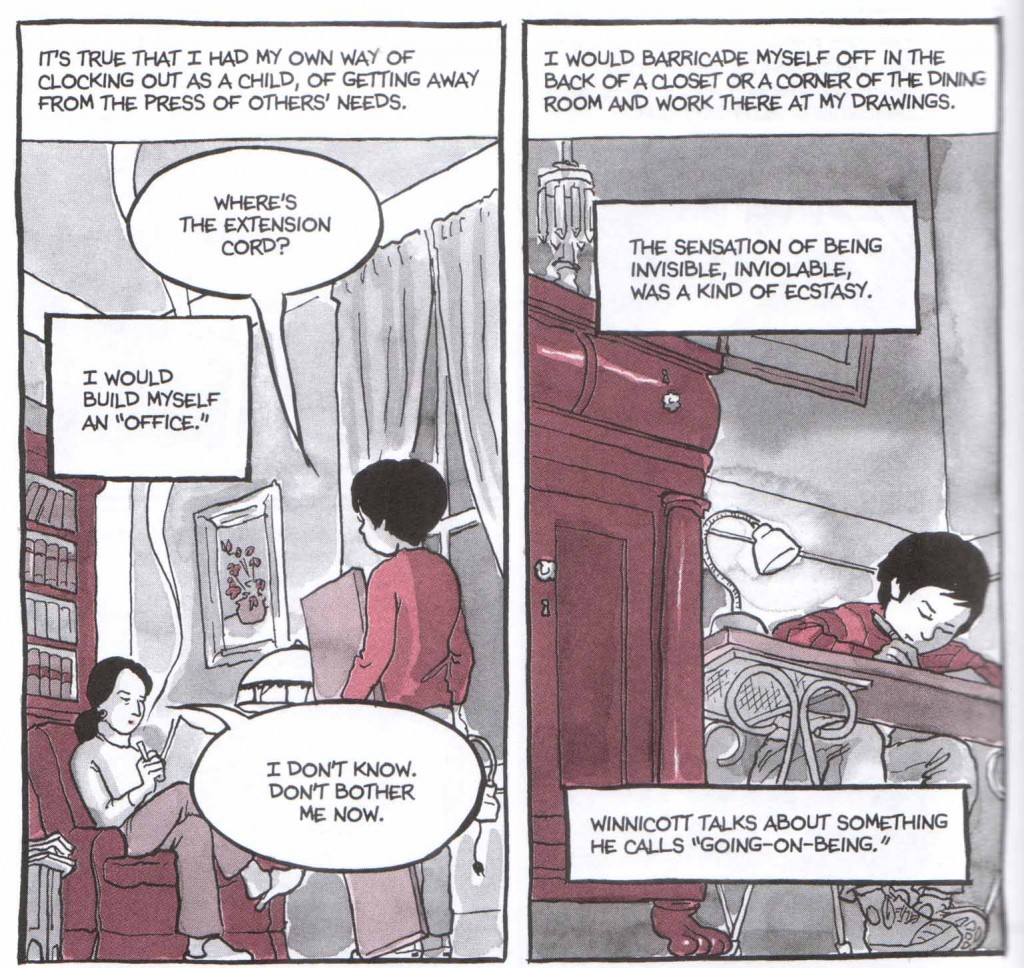

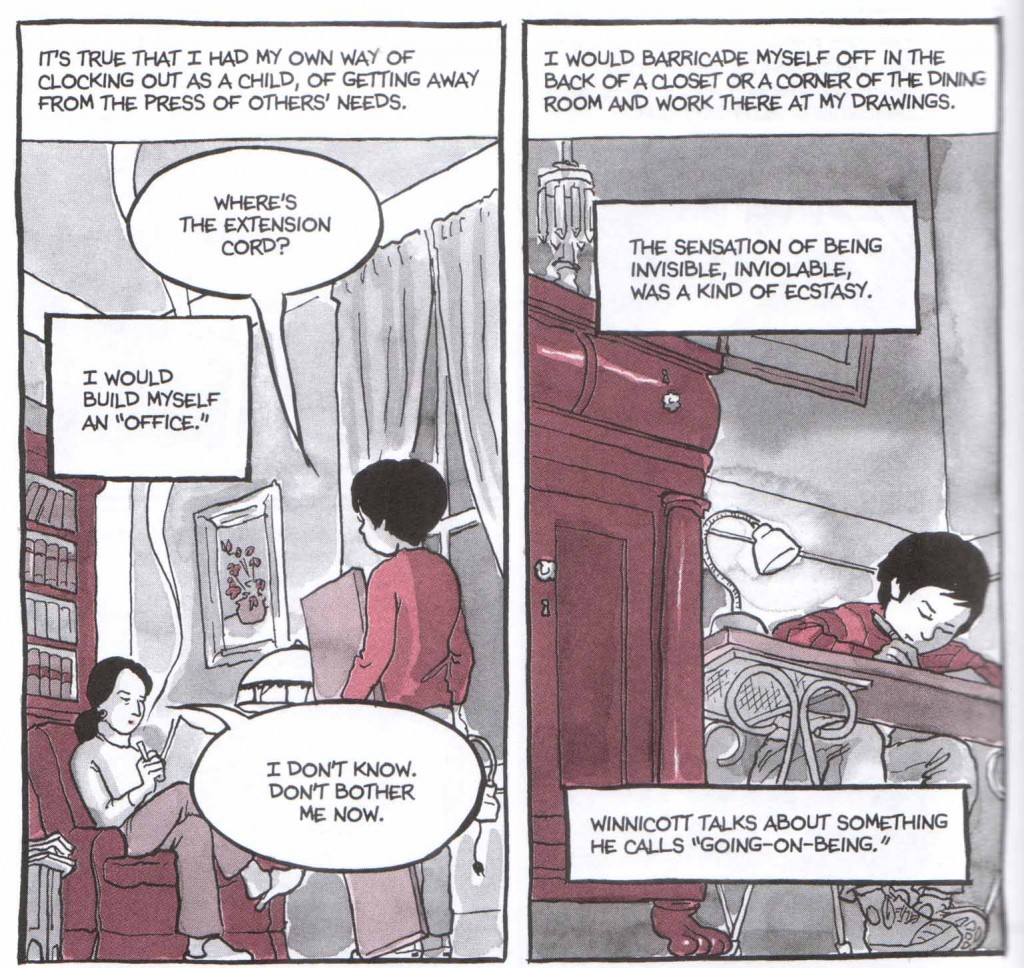

The womb is echoed in a jumble of details and associations: her special cramped office in her childhood home; her drawing of a gynecological examination as a child; Donald Winnicott’s analysis of a child who describes the darkness of the womb…

…the uterine-shaped plexiglass dome of a Dr. Seuss book about sleep…

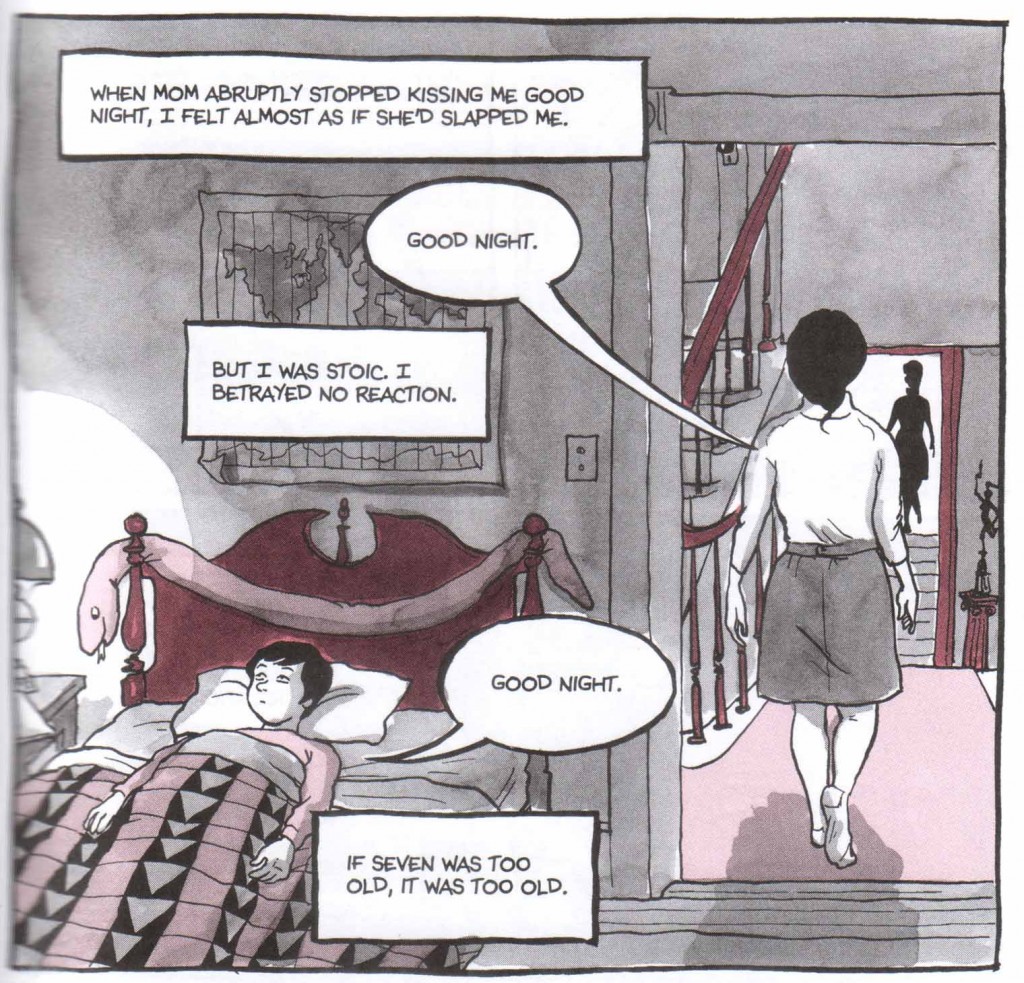

…and hence to her mother’s decision not to kiss her while she is lying in her womb-like bed. Her mother’s back turned from her and hence as expressionless as the thin silhouette she casts in the mirror across the hallway; the map of the world hanging over her bed now half-shrouded in shadow and uncertainty (see first image above); the child’s face half in darkness and half in light.

This paramount failure to connect (reasserted at various points in the comic) is echoed in the final pages of that chapter where Bechdel is enveloped in darkness in her room, the black full page bleed being the very substance of dreams in the vernacular of the comic (here applied to firm reality).

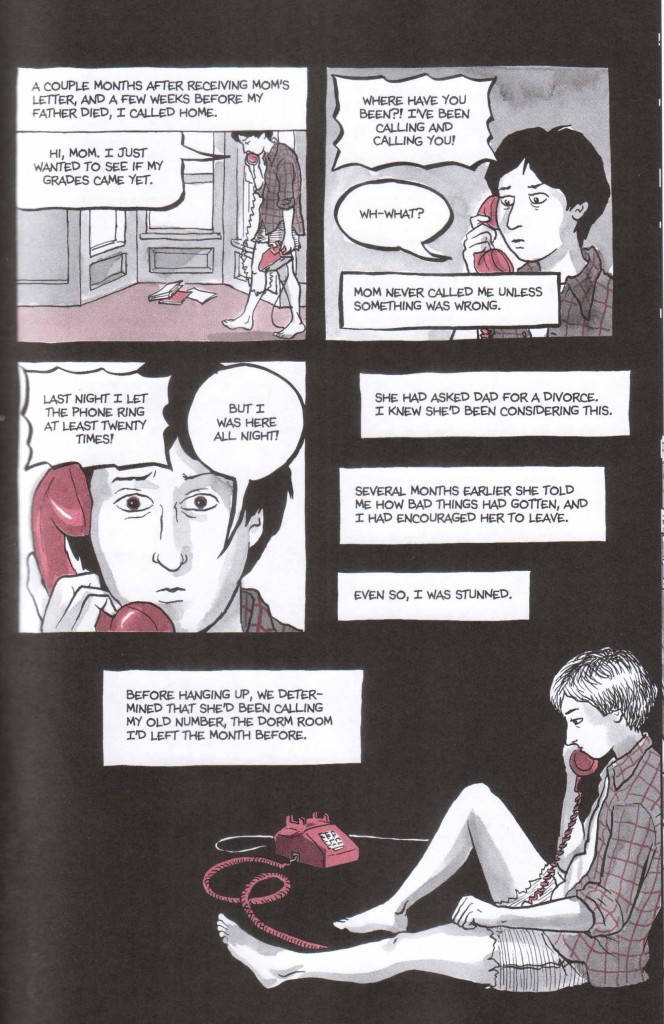

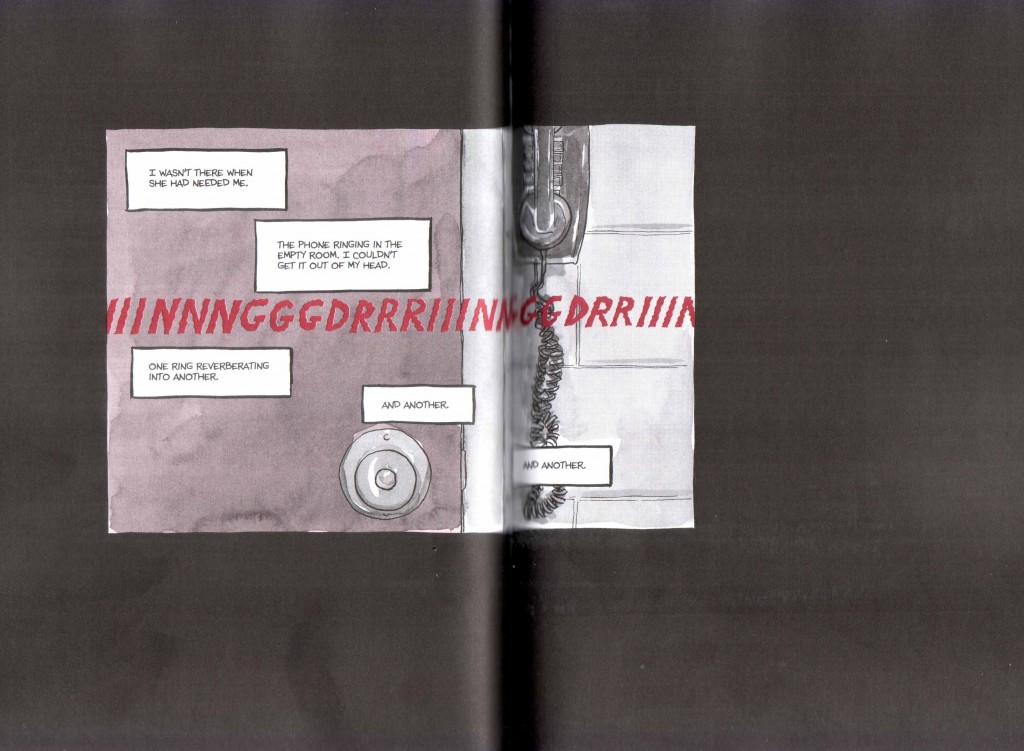

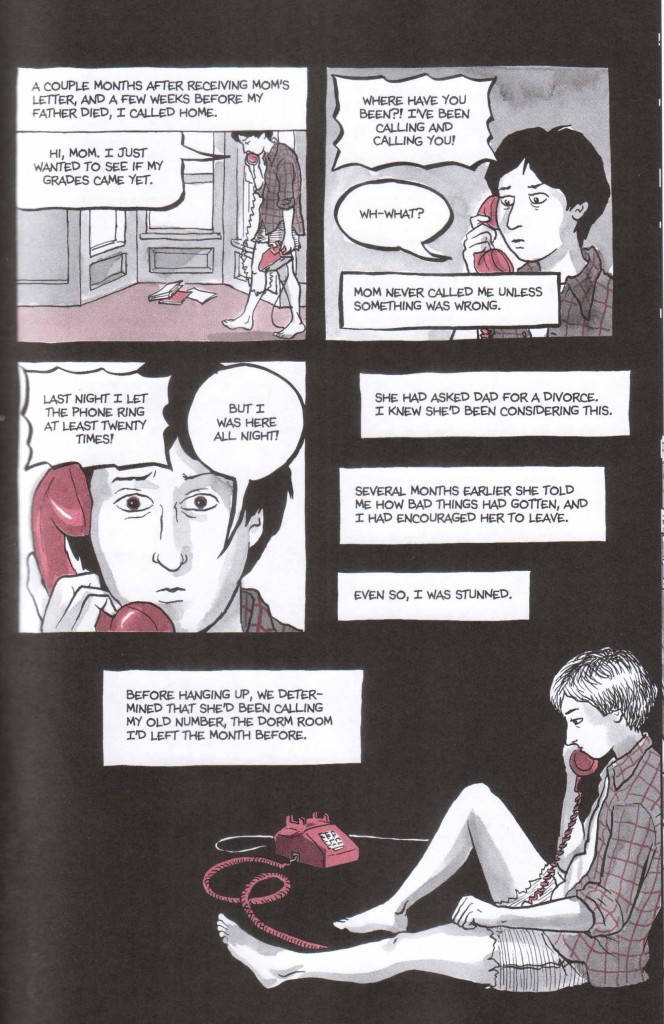

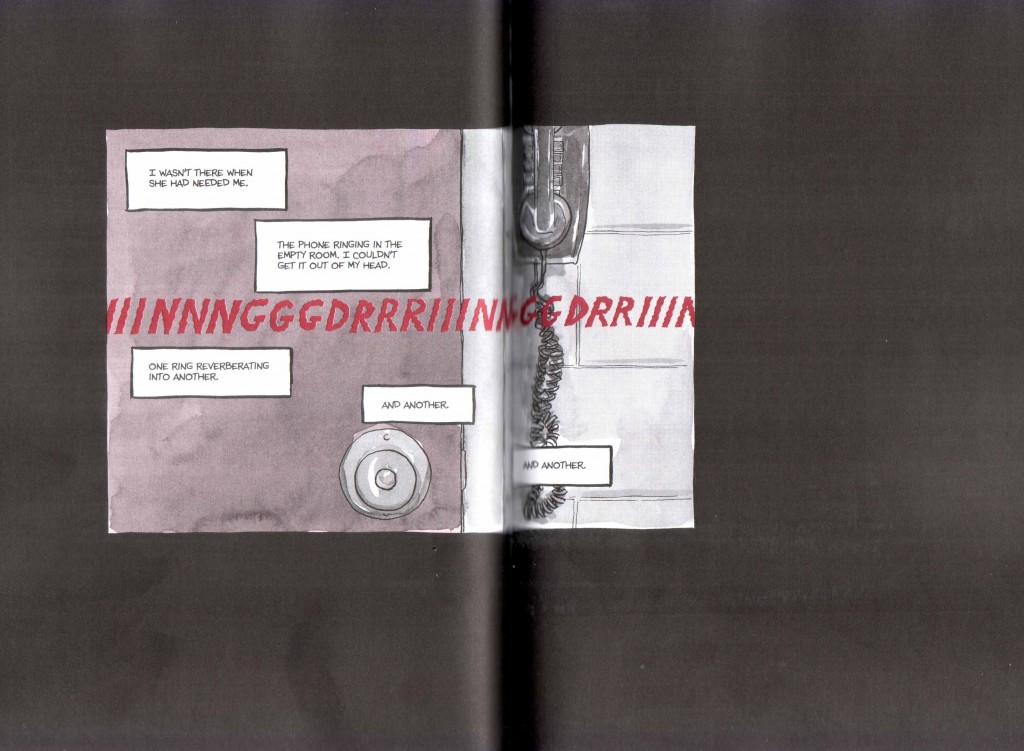

The final image of that chapter is almost quotidian by comparison showing Bechdel’s old dorm room telephone ringing, the room from which she moved out just before her father died, a door knob preceding this on the page, these points in the darkness highlighted by their proximity to the captions (“And another. And another.”).

A lifeline and a doorway between worlds. A breast and an umbilical cord. The severed communication resounding through the pages of the chapter just as the ring stretches across the breath of this final panel.

Earlier in the chapter, there is a scene where Bechdel asks her mother for an extension cord (“I don’t know, don’t bother me,” her mother replies) before mirroring her mother in this desire for isolation, setting up an “inviolable” area of creation.

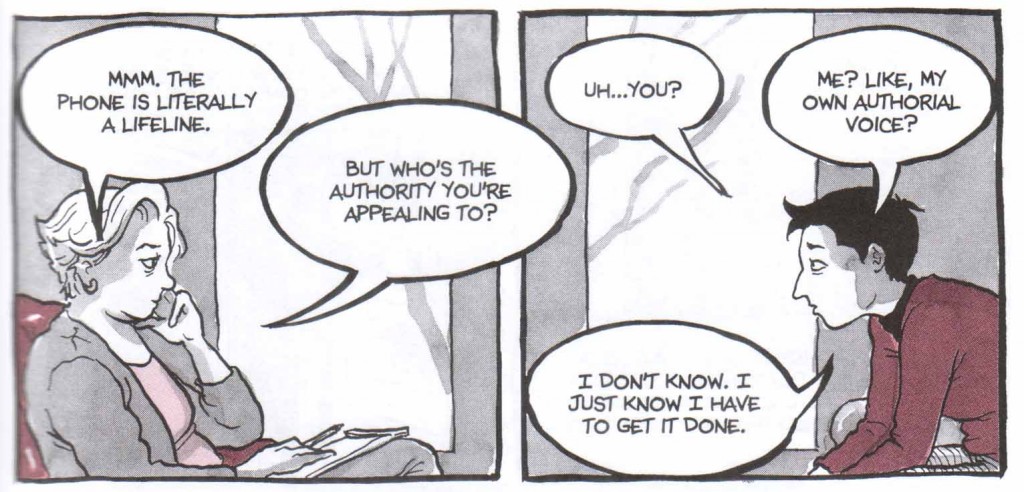

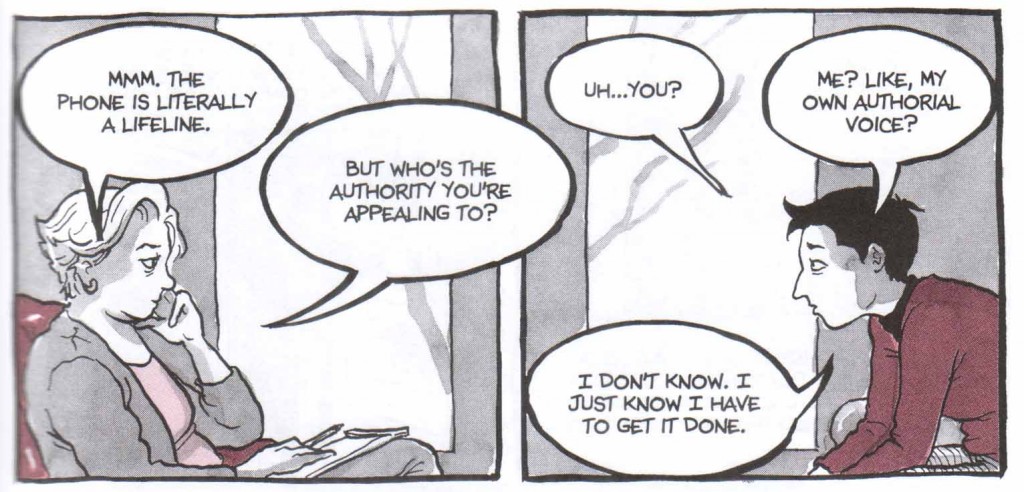

Just a few pages before this near the start of the chapter (pg 123), her therapist asks, “The phone is literally a lifeline. But who’s the authority you’re appealing to?” The question is asked in relation to the chapter’s opening dream which sees Bechdel trying to call the police on an “intra-campus phone system” to absolutely no effect. Bechdel interprets her punching of the phone keys in the dream as an act of writing and points to her therapist or her “authorial voice” as the authority she is appealing to.

Her final answer seen in that missed phone call from her mother at chapter’s end—a phone call advising impending divorce (and soon death)—is direct but unexpected. The progress is distinctly logical but the overall effect, with its chronological jumps and uncertainties, quite impressionistic. It is an impressive feat of storytelling and the chapter a high point in the comic. The rest of Are You My Mother? is less consistent. The magic starts, skips, and stops; the art wavers in consistency but occasionally soars; the text demands recursions; that balancing act always precarious, the battles sometimes lost; for all its faults a book well worth reading.

Notes

[1] From Alice Miller’s The Drama of the Gifted Child: “True autonomy is preceded by the experience of being dependent, first on partners, then on the analyst, and finally on the primary objects.” [back]

Further Reading

The marketing power of Houghton Mifflin Harcourt is something to behold and there have been a slew of articles by the mainstream press. This may well be the most extensively reviewed comic of 2012 with the press being overwhelmingly positive. Here are some of the more detailed articles:

(i) Meghan O’Rourke’s review at Slate is probably the best review of Bechdel’s comic online:

“What Winnicott—and Bechdel—was interested in was what happened when this crucial mother-child mirroring broke down, and the child became precociously attuned to the mother’s needs instead of her own. Likewise, Alice Miller’s The Drama of the Gifted Child chronicles the kinds of abuse children suffer at the hands of narcissistic parents, particularly mothers.”

(ii) Interviews and authorial revelations: Hilary Chute at Critical Inquiry, Heather McCormack at Library Journal, Shauna Miller at The Atlantic, Peter Terzian at the Paris Review