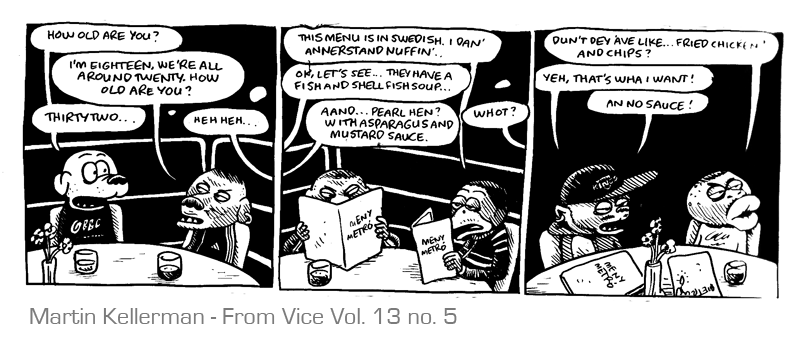

Are comic books really not for kids anymore if their pretenses at intellectualism are taking shape as the miasma of rhetoric excusing the straightforward use of crude racist stereotypes by white male cartoonists as satirical and over the heads of the rest of (x) unsophisticated rubes. And hey, is the racist iconography in question even really a known quantity, or something the cartoonist deliberately inserted to provoke reader (x)’s assumption that it is exactly what it looks like, dummy (x).

I’ve used sarcasm to draw your inference that I meant the opposite of the words I just typed (I am very sophisticated). Ugly, stereotyped, demeaning images of non-white people are racist. As Dr. Henry Louis Gates Jr has pointed out specifically, sambo art’s past prevalence (or onmi-presence) in society was a deliberate social tool to shape dominant white attitudes about black people with the specific goal of dehumanizing and politically repressing them, which is exactly what happened (continues to happen). The lines on paper, the blots of ink, when arranged in this way traces a current of malice from history to the artist’s hand today. Even though it’s fashionable in some circles to affect a veneer of cash-and-carry general repulsiveness as a shield against any specific allegation of consciously doing ill with ink on paper, degrading racist cartoons do hurt people.

This is supposed to be funny under the assumption that this is scenario is alien to white Westerners. It is not because it is not.

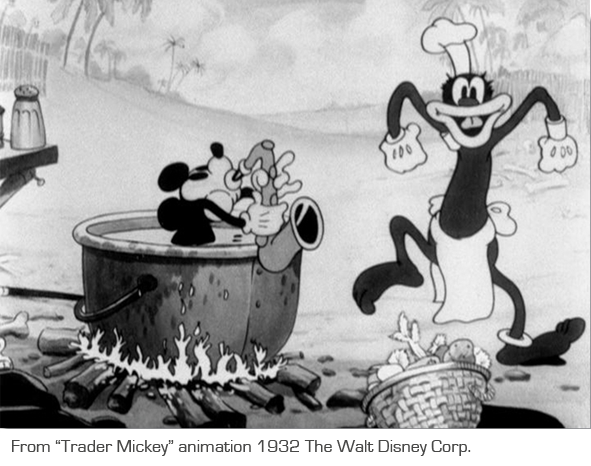

How we cartoon people is important, even if we’re cartooning people as animals. I’ve written previously (before I was officially HU’s correspondent on Furries) about the furry detective comic Blacksad and transposing human racial attributes onto a setting with anthropomorphic animals. Blacksad is not an example of a lucid and well-measured application of this trope. In fact, it’s a disaster. In contrast to Blacksad’s racialized concept of speciation, I remember reading the cartoonist Dana Simpson mentioning in a response to a reader question that using funny animals was a way to avoid racial prejudice in a reader as a barrier to empathizing with each character. Cute animals are just cute animals. The pitfall here is that without context, characters in this setting can sometimes be read as white by default. Still, some funny animal cartoonists elect to take the route of no thought or consideration and draw the same offensive stereotypes, but now it’s a cat. This is an old idea. Look at Mickey, here.

The Mouse’s features mirror those of his companion, though it’s clear that Mickey is supposed to read as white, in blackface, and his purpose in this cartoon is to humiliate his black counterparts. Of course these cartoons have been buried as an embarrassing fart of less-enlightened history. I can’t help compare the racist Mickey Mouse pictures to their contemporaries from the old Fleischer Studios, where black music and performance were showcased; rotoscoping technology turning the magnificent Cab Calloway into a spooky ghost in Snow White. Bimbo the dog shares Mickey’s white/black distribution of shade, but less of the minstrel attribution.

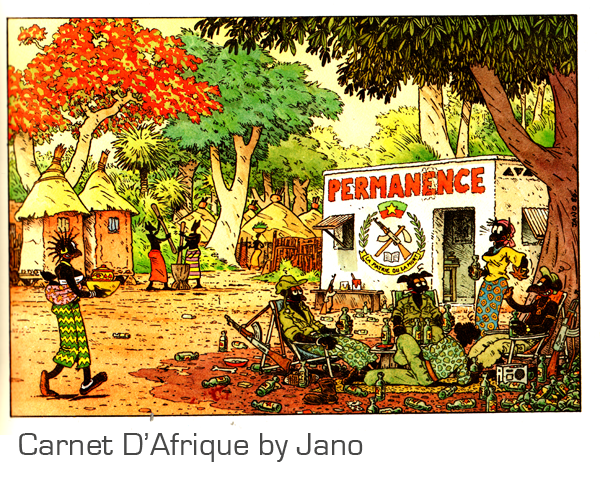

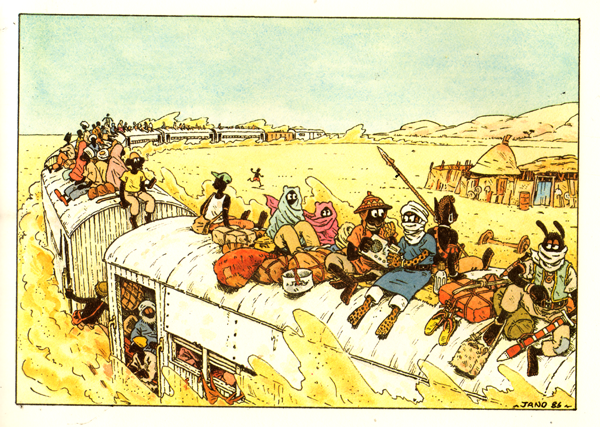

When I was studying comics at the SCAD campus in Lacoste, France, and later goofing around in Spain, I discovered that cartoonists were still drawing funny animals this way. In Madrid, a sambo holding a saxophone at a jaunty angle spray-painted on the wall with the text “jazz club,” etc etc etc. I was shocked and puzzled at the ubiquitous caricature of non-white people I saw in the comics shops in the Latin Quarter and Montmartre and Angouleme that only the boldest and self-consciously controversial American artists would think of rendering. In my extreme naivete, I just didn’t… mention…. how weird it was, at the time. In Apt, I even picked up second-hand copies of two of Jean Leguay (aka Jano’s) travelogues, Carnet D’Afrique and his collaboration with fellow cartoonists Dodo and Ben Radis, Bonjour les Indes. Inside, Jano’s uproarious, chaotic, sensational, grotesque drawings show an exaggerated portrait of the places the French cartoonists is fond of visiting.

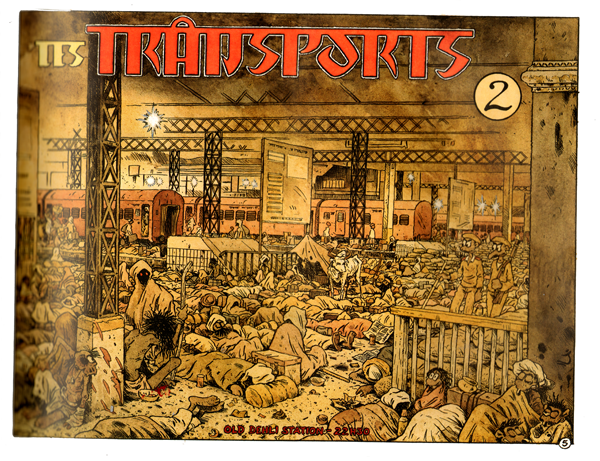

From Bonjour les Indes.

While often poking fun at clueless white tourists, the book generally portrays Indian people as dirty, simple, venal, self-interested and exotically dangerous, mostly for comedic effect.

His characters are ducks, dog-things, sometimes vaguely bovine creatures with generally blank features, skin like pitch and painted red lips, their individual qualities, background, social status differentiated primarily by costume. It’s a jarring tableau, the post-imperial plundering of faux-quotidian details for broad, sometimes brutal comedy intertwined with mundane, naturalistic, documented daily life that we Americans omit from our envisioning of the world when we reflexively chide ourselves for our “first world problems.” Jano’s travelogues sometimes humanize overlooked experiences while simultaneously reveling in images, exoticism and racist stereotypes meant to dehumanize them. We see people in markets, at the cinema, on a train, buying a guitar, and on the last plate of Carnet D’Afrique, a comic beheading with a sword. Jano has an eye for detail, but too often he misuses it. Instead of highlighting the richness and variety of the lives of his subjects, he instead focuses on sordidness, a cheap thrill here, an ugly little chuckle there, which diminishes them. Gallows humor is a wonderful thing, but artists should keep in mind who erects the gallows and who swings from them.

Reading these books, I can’t really find a reason why Jano draws the people in his travelogues as anthropomorphic animals instead of humans. What thought went into the creation of these images other than “this will look cool?” My great fear, especially writing my own funny animal comic, is that there really is no right way to translate human culture into a world of differentiated animal species that isn’t glib, clumsy and married to racist narratives. Are animal people inherently cruder and cheaper and less dignified than people-people? Was that the whole purpose of the funny animals’ creation? Does drawing a racist image as a dog deflect from the awfulness of the image, or does it enhance what is already a purposeful dehumanization? If furry art is, as I think it is, or ought to be, an imaginative space, furry artists have to consider the historical backdrop in which funny animals have been used and misused to represent people, and do better. Much, much better than’s been done before.

For god’s sake at least better than this. Yiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiikes.